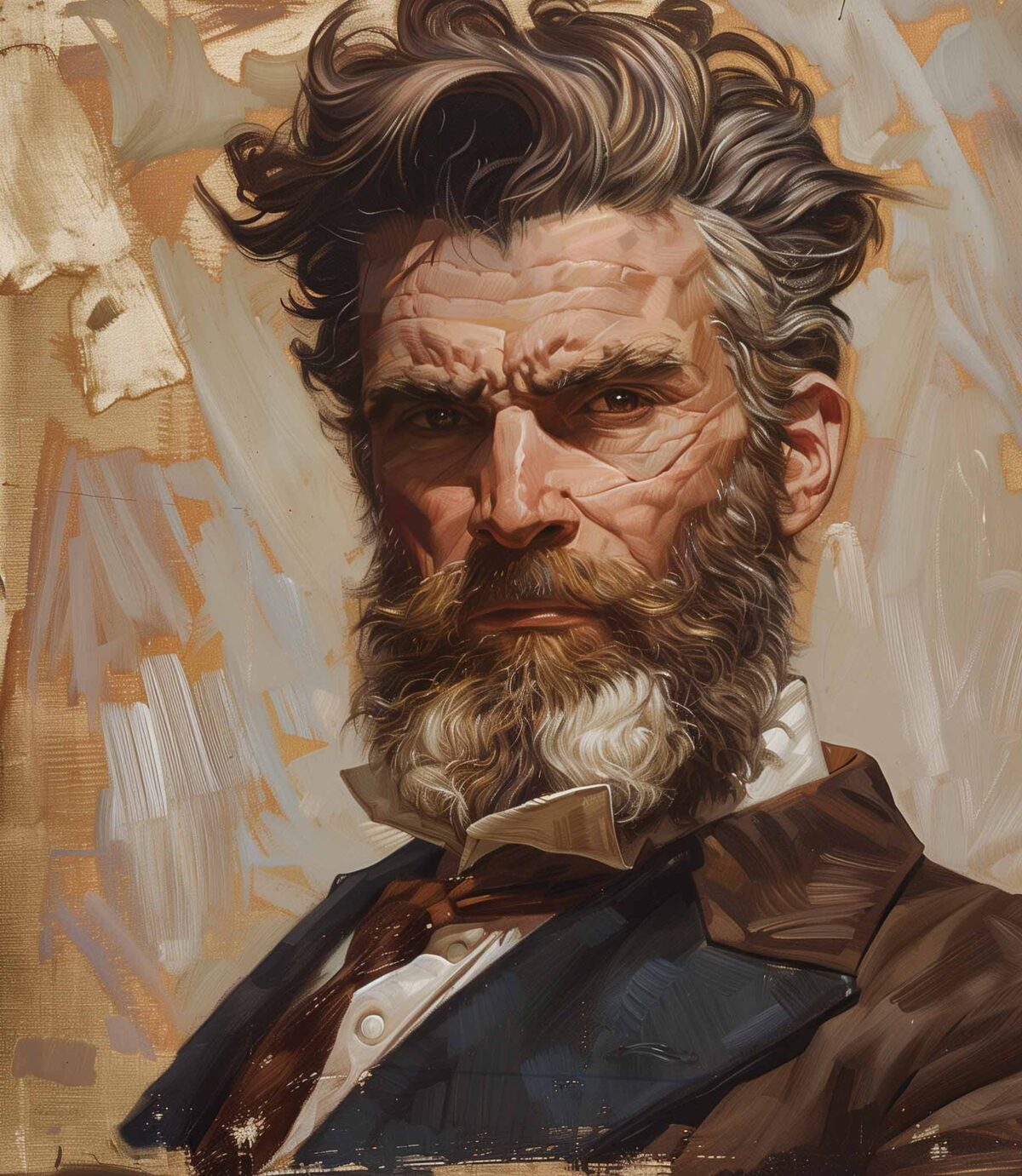

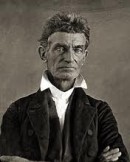

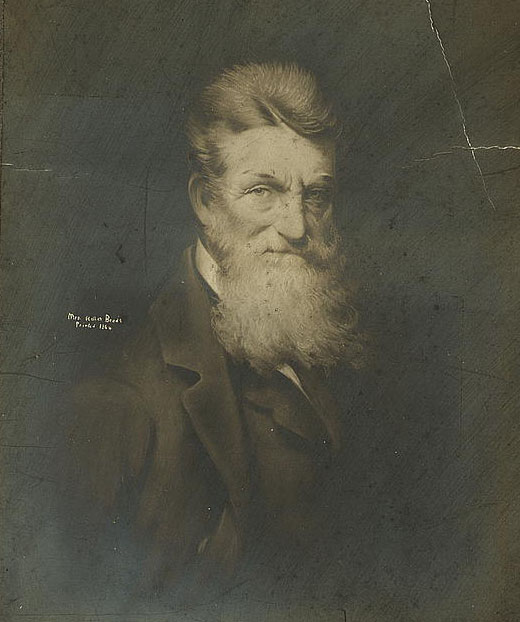

Facts about John Brown, an Abolitionist

John Brown Facts

Born

May 9, 1800, Torrington, Connecticut

Died

December 2, 1859, Charles Town, Virginia

Accomplishments

Activist in the abolitionist movement

Raid On Harpers Ferry

John Brown Articles

Explore articles from the History Net archives about John Browns Raid On Harpers Ferry

» See all John Brown’s Raid Articles

John Brown summary: John Brown was a radical abolitionist whose fervent hatred of slavery led him to seize the United States arsenal at Harpers Ferry in October 1859. It is widely believed his intention was to arm slaves for a rebellion, though he denied that. Hanged for treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia, Brown quickly became a martyr among those seeking to end slavery in America.

John Brown summary: John Brown was a radical abolitionist whose fervent hatred of slavery led him to seize the United States arsenal at Harpers Ferry in October 1859. It is widely believed his intention was to arm slaves for a rebellion, though he denied that. Hanged for treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia, Brown quickly became a martyr among those seeking to end slavery in America.

John Brown’s Youth

John Brown was born May 9, 1800 in Torrington, Connecticut, but spent much of his youth in Ohio. His parents instilled in him a strong belief in the Bible and a strong hatred of slavery, and his father taught him the family trade of tanning animal skins. He was foreman in the family’s tannery before moving to Massachusetts, in hopes of becoming a minister. After he married Dianthe Lusk, they moved to Pennsylvania, where he established a tannery of his own. The couple wed in 1820; before Dianthe’s death in 1831, she bore him seven children. Less than a year after her passing, he married a 16-year-old named Mary Anne Day. That union produced 13 more offspring.

Brown was not a particularly good businessman, and what skills he had declined as his thinking became more metaphysical. He bought and sold several tanneries, engaged in land speculation, raised sheep, and established a brokerage for wool producers, but his financial situation deteriorated. His thoughts turned more and more to people he considered oppressed; had he lived in a later era, he might have become a socialist.

Abolitionist John Brown In The Underground Railroad

Often seeking the company of blacks, he even lived in a freedman’s community in North Elba, New York, for two years. He became a conductor in the Underground Railroad and organized a self-protection league for freemen of color and fugitive slaves.

By the time he was 50 years old, Brown was convinced God had selected him as the champion to lead slaves into freedom, and if that required the use of force, well, that was God’s will, too. After the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 gave citizens of those two territories the right to choose for themselves whether the territories would permit or prohibit slavery, Brown, like many abolitionists, moved to Kansas, taking five of his sons with him. Fervent members of the abolition movement were determined that when the territory was ready to enter the Union as a state, it would do so as a free state. On the other side, many defenders of slavery were also pouring into Kansas, in order to secure it for the pro-slavery faction.

On May 21, 1856, Missouri “border ruffians” attacked the anti-slavery town of Lawrence, pillaging and burning. Two days later, Charles Sumner, a U.S. Senator from Massachusetts, was severely beaten with a cane on the Senate floor by Senator Preston Brooks of South Carolina because of verbal attacks the virulently anti-slavery Sumner had made on another South Carolinian.

John Brown’s Cause Turns To Violence

Rumors spread that the border ruffians intended to attack the anti-slavery settlers on Pottawatomie Creek, Kansas; Brown and his family were among the abolitionists in this sharply divided area. On the night of May 24, Brown, with four of his sons and two other men, rode to the homes of three pro-slavery settlers near Dutch Henry’s crossing on Pottawatomie Creek; Brown intended to “Sweep the Pottawatomie of all pro-slavery men living on it.” They dragged James Doyle and two of his sons, William and Drury, from their farmhouse. When the trio tried to escape, James Doyle was shot down and his sons hacked to death with short sabers. Doyle’s wife, daughter and 14-year-old son John were spared. At the home of Allen Wilkinson, the avengers ignored the pleas of his sick wife and two children and took Wilkinson away as a prisoner. He was soon dispatched with one of the swords.

At the third home they visited, Brown’s band killed William Sherman with their swords and threw his body into a creek. Other men and a woman found at Sherman’s home were not harmed. Through it all, Brown had decided, god-like, who would die and who would be spared, though according to his followers he did not actively participate in the executions. Whenever he was questioned about the events of that night, he was evasive.

The events at Lawrence and Pottawatomie caused the territory to erupt in guerrilla warfare, giving it the name “Bleeding Kansas.” Brown’s name became known to the nation, a Christian warrior to many who opposed slavery and a demented murderer to many other people.

John Brown’s Raid On Harper’s Ferry

On the night of October 16, 1859, Brown led 21 followers—five black men and 16 white ones, including two of Brown’s sons—on a raid to seize the U.S. Arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia), where the Shenandoah River joins the North Branch of the Potomac. More than one version exists of what his plans were for the weapons he hoped to make off with. Some say he intended to create a state of free blacks in the mountains of western Virginia and Maryland. Others say he hoped to create an army of former slaves and freemen to march through Dixie, forcing slave owners to free their slaves. Brown himself may not have been entirely clear on what the next step would be, but he had convinced a number of Northern abolitionists to provide financial support for his actions, here and elsewhere.

Brown’s raiders captured a number of prisoners, including George Washington’s great-grand-nephew, Lewis Washington. Local militia trapped Brown and his men inside the arsenal’s firehouse. During the short siege, three citizens of Harpers Ferry, including Mayor Fontaine Beckham. were killed. The first person to die in John Brown’s raid, however, had been, ironically, a black railroad baggage handler named Hayward Shepherd, who confronted the raiders on the night they attacked the town. On October 18, a company of U.S. Marines, under the command of Army lieutenant colonel Robert E. Lee, broke into the building. Ten raiders were killed outright and seven others, including a wounded Brown, were captured.

Read more about John Brown’s Raid On Harpers Ferry

Brown Sentenced To Death

He was tried and convicted for murder, conspiracy to incite a slave uprising, and treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia. He was hanged at Charles Town, the county seat near Harpers Ferry, on December 2. Among those watching the execution, “with unlimited, undeniable contempt” for Brown, was the future assassin of President Abraham Lincoln, John Wilkes Booth.

Brown had denied any plan “to excite or incite the slaves to rebellion or to make insurrection.” He never intended to commit murder or treason or to destroy property, he claimed—though earlier that year he had purchased several hundred pikes and some firearms.

“Now if it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice, and mingle my blood further with the blood of my children and with the blood of millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel, and unjust enactments, I say let it be done,” he said.

The “unjust enactments” included the Constitution, the Missouri Compromise of 1820, the Kansas-Nebraska Act, and the Supreme Court’s ruling in the Dred Scott decision of 1857.

John Brown’s Legacy

Initial reports of the raid on Harpers Ferry in Southern newspapers tended to view it as an isolated incident, the work of a mad fanatic and his followers. But when information began to surface that Brown had discussed his plans—to what extent is not known—with Northern abolitionists and had received moral and financial assistance, Southern attitudes turned sour. Many in the abolition movement painted Brown as a martyr, convincing many Southerners that abolitionists wished to commit genocide on white slave owners. Among abolitionists, Brown served as an inspiration to strive ever harder to abolish “the peculiar institution.”

North and South drew even farther apart from each other. John Brown and his Harpers Ferry raid are often referred to as the match that lit the fuse on the powder keg of secession and civil war. Even today, debate continues on how Brown should be remembered: as a martyr to freedom, as a well-intended but misguided individual, or as a terrorist who hoped for revolution and, perhaps, murder on a grand scale.

Articles Featuring John Brown From History Net Magazines

John Brown Featured Article

The Madness of John Brown

By Robert E. McGlone

Old John Brown’s failed attempt to launch a “war” against slavery ended just after dawn on October 18 in a bloody rout on the grounds of the federal armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. Brown himself was wounded when a squad of Marines picked from a force of 86 sent by President James Buchanan—all the force he could muster despite widening panic over the rumored slave uprising—overwhelmed the remnant of Brown’s tiny force at dawn on the second day of the “invasion.”

After a six-day trial, a Virginia court convicted Brown of three capital offenses—murder, treason and conspiracy to incite a slave uprising. Judge Richard Parker sentenced him to hang 30 days later.

Brown’s raid sent shock waves through the nation and found few outright apologists. Nonresistant abolitionists praised Brown’s ends, but many of them deplored his means. The raid reverberated throughout the political season. The 1860 platform of the Republican Party officially “denounced the lawless invasion of armed forces of the soil of any State or Territory, no matter under what pretext….” Listed among the causes of South Carolina’s secession from the Union in December 1860 was the refusal of the states of Ohio and Iowa to “surrender to justice fugitives” from Brown’s raid, who were “charged with murder, and with inciting servile insurrection in the State of Virginia.”

At his sentencing, Brown reaffirmed his commitment to his cause and accepted his sentence with memorable words. “Now, if it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice, and mingle my blood further with the blood of my children and with the blood of millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel, and unjust enactments,” Brown told the court, “I say, let it be done.” While awaiting the date of what Brown insisted in widely published letters to friends in the North was to be his “public murder,” he pleaded eloquently—not for himself but for the slaves. He insisted that he was “worth inconceivably more to hang than for any other purpose.” In thus embracing martyrdom, Brown himself became a cause among reformers and intellectuals in the North.

Southerners, on the other hand, were convinced that if Brown’s raid had succeeded, the slaves he incited to rebel would have slain their masters. Worse, Brown’s captured correspondence seemed to prove he had the confidential support of influential Northerners. Widespread popular protests in the North on the day of his execution infuriated Southerners such as Virginia Governor Henry Wise, who admired Brown’s courage and forthrightness but condemned “those who sent him.” Despite appeals for clemency, Wise staunchly refused to commute Brown’s sentence.

Southern partisans carried their hatred of Brown to the grave. Six years after Harpers Ferry, as John Wilkes Booth fled authorities following his assassination of Abraham Lincoln, he remembered witnessing Brown’s hanging. “I looked at the traitor and terroriser,” Booth wrote to a friend, “with unlimited, undeniable contempt.” If abolitionists praised Brown’s compassion for the “poor slave,” to white Southerners he was anarchy incarnate.

Despite Brown’s undeniable impact on American history, Brown scholarship has progressed sporadically, and he has inspired only about two dozen scholarly biographies in the 150 years since his capture at Harpers Ferry. Questions about Brown’s readiness to use violence, the roots of his “fanaticism” and his sanity have plagued researchers. The belief that Brown suffered from mental illness distances us from him.

Indeed, as Brown himself understood, the claim that he was “insane” threatened the very meaning of his life. Thus at his trial he emphatically rejected an insanity plea to spare him from the hangman. When an Akron newspaperman telegraphed Brown’s court-appointed attorneys in Richmond that insanity was prevalent in Brown’s maternal family, Brown declared in court that he was “perfectly unconscious of insanity” in himself.

As Brown understood it, the “greatest and principal object” of his life—his quest to destroy slavery—would be seen as delusional if he were declared insane. The sacrifices he and his supporters had made would count for nothing. The deaths of his men and the bereavement of his wife would be doubly tragic and the attack on Harpers Ferry robbed of heroism, its purpose discredited.

In letters to his wife and children, Brown acknowledged that his raid had ended in a “calamity” or a “seeming disaster.” But he urged them all to have faith and to feel no shame over his impending fate.

While his half brother Jeremiah helped gather affidavits supposedly attesting to Brown’s “monomania,” or-single minded fixation on eradicating slavery, John’s brother Frederick went on a lecture tour in his support. Neither Jeremiah nor anyone else in John Brown’s large family renounced the raid.

When it comes to Brown’s war against slavery, the question of his mental balance must nevertheless be addressed. By the time of the Harpers Ferry raid, some of his contemporaries had already begun to question his sanity. As they insisted, was not the raid itself evidence of an “unhinged” mind? Wasn’t Brown “crazy” to suppose he could overthrow American slavery by commencing a movement on so grand a scale with just 21 active fighters?

No one can doubt that Brown sought to elevate the status of African Americans. Throughout his adult life, he conceived projects to help them gain entry into the privileged world of whites. As a youth he helped fugitive slaves on the Underground Railroad; as a prospering farmer and town builder, he proposed adopting black children and founding schools for them. In 1849 he moved his family to North Elba, N.Y., to teach fugitives how to maintain a farm.

He held a two-day convention in Canada to secure the participation of fugitive American blacks in his planned war on slavery. He wrote a declaration of independence on their behalf. He respected and raised money for “General” Harriet Tubman and called his friend Frederick Douglass “the first great national Negro leader.” Yet to the extent that in his projects he envisioned himself as a mentor, leader or commander in chief, Brown’s embrace of egalitarianism was, paradoxically, paternalistic. He solicited support from blacks for the war against slavery but not their counsel in shaping it.

Despite that, his black allies never called seizing Harpers Ferry crazy. Although Brown had been hanged for his actions, Douglass insisted the raid had lit the fire that consumed slavery. Brown chose to open his war against slavery at Harpers Ferry, W.E.B. Du Bois wrote in 1909, because the capture of a U.S. arsenal would create a “dramatic climax to the inception of his plan” and because it was the “safest natural entrance to the Great Black Way” through the mountains from slavery to freedom in the North.

Harpers Ferry wasn’t Brown’s first foray onto the national stage. In 1857 his band of men had killed several proslavery settlers in “Bleeding Kansas,” hacking to death five men along Pottawatomie Creek with short, heavy swords. Scholars differ on whether the killings should be considered murders or acts of war following the proslavery sack of Lawrence just days before. I have found evidence that Brown and his sons saw their attack as a kind of preemptive strike against men who had threatened violence against freestaters. But to understand is not necessarily to justify or excuse. How a deeply religious man could commit such an act is a question one cannot ignore in assessing Brown’s mind.

Du Bois understood that Brown’s recourse to violence in killing “border ruffians” in Kansas and his attempt to seize the armory at Harpers Ferry in order to arm slaves had caused “bitter debate as to how far force and violence can bring peace and good will.”

But Du Bois, a co-founder of the NAACP, did not think slavery could have been ended without the Civil War. He concluded that “the violence which John Brown led made Kansas a free state” and his plan to put arms in the hands of slaves hastened the end of slavery. Du Bois’ book John Brown was a “tribute to the man who of all Americans has perhaps come nearest to touching the real souls of black folk.” African-American historians, artists and activists have long eulogized Brown as an archetype of self-sacrifice. “If you are for me and my problems,” Malcolm X declared in 1965, “then you have to be willing to do as old John Brown did.”

Blacks’ reverence for the memory of Brown has not inspired those mainstream historians uncomfortable with Brown’s reliance on violence. The belief that he may have suffered from a degree of “madness” has echoed down through the decades in Brown biographical literature. In his popular 1959 narrative The Road to Harpers Ferry, J.C. Furnas argued that Brown was consumed by a widespread “Spartacus complex.”

But Furnas also found that “certain details of Old Brown’s career” and writings evidenced psychiatric illness. Brown might have been “intermittently ‘insane’…for years before Harpers Ferry,” Furnas specu- lated, “sometimes able to cope with practicalities but eventually betrayed by his strange inconsistencies leading up to and during the raid—his disease then progressing into the egocentric exaltation that so edified millions between his capture and death.”

Careful historians like David M. Potter reaffirmed the centrality of the slavery issue in his posthumously published synthesis The Impending Crisis, 1848-1861, but even Potter conceded that Brown “was not a well-adjusted man”—despite the fact many abolitionists shared his belief that the slaves were restive.

In 1970 historian Stephen B. Oates sought to bridge the rival biographical traditions by depicting Brown as a religious obsessive in an era of intense political conflict. Oates’ Brown was not the Cromwellian warrior of early legend builders. Nor was he the greedy, self-deluded soldier of fortune of debunkers.

He was a curious, somewhat schizoid amalgam of the legend builders’ martyr and his evil doppelganger. This Brown possessed courage, energy, compassion and indomitable faith in his call to free the slaves. He was also egotistical, inept, cruel, intolerant and self-righteous, “always exhibit[ing] a puritanical obsession with the wrongs of others.”

Oates was doubtful that historians might ever persuasively identify psychosis in a subject they studied. He repudiated historian Allan Nevins’ belief that Brown suffered from “reasoning insanity” and “ambitious paranoia,” but he declared that Brown was not “normal,” “well adjusted” or “sane” either (later dismissing these terms as meaningless).

But reference to Brown’s “glittering eye”—a telltale mark of insanity in 19th-century popular culture—invited Oates’ readers to conclude that Brown was touched with madness after all. Finding in Brown an “angry, messianic mind,” Oates straddled the two biographical traditions. For three decades, his portrait of Brown has perpetuated the image of mental instability.

To get to the roots of Brown’s mental state, we must turn to those closest to him for help. Analysis of the scores of letters written by members of both Brown’s immediate family and the extended family he referred to as the “connection” reveal a John Brown quite different from the self-absorbed, humorless, rigid, imperious, driven fanatic portrayed by some biographers.

Letters Brown exchanged with his father, his wife and his dependent and grown children over several decades reveal a warmer, more engaged father than heretofore pictured. Although he moved his family frequently, he was not a “wanderer” or a “loner.” Brown and his father, “Squire” Owen, remained fast friends despite the latter’s exacting standards of piety and worldly success for his eldest son. Owen’s home in Hudson, Ohio, remained a vital part of his son’s emotional universe to the end.

John Brown asked forgiveness of his wife for his long absences while driving cattle to market or selling prize sheep, and he often complained of homesickness. He loved to hold his children and sing to them; he regularly brought the little ones presents, and he often teased his adolescent sons about their preoccupation with girls.

In 1846 Brown met the tragic death of daughter Amelia—“little Kitty”—and the loss of other children soon after, despite his own grief, with words of encouragement and reaffirmations of faith in a compassionate God to his bereaved second wife, Mary Ann, who bore him 13 offspring. Indeed, he was resilient in the face of God’s “afflictive Providences” and was apparently seldom “blue” for long periods. The only time in his adult life of which we have any record when he was genuinely depressed for months or even weeks was while mourning the death of his beloved first wife, Dianthe, in 1832.

A Calvinist who believed that earthly life was a time of testing and trial, Brown accepted reversals with courage and renewed hope. Even after the failure of speculative enterprises he entered into with his father or his neighbors, Brown was resilient. After a variety of disappointments, Brown faced starting over in collaboration with his adult sons with fortitude and optimism.

Although he later despaired of his sons’ religious apostasy, Brown defended his faith in the Bible and his belief in “the God of my fathers” to them and also to his teenage daughter, Annie. The dissenters all remained close to their father despite their rejection of his biblical Christianity.

Even though he preached serious-mindedness, Brown’s temperament was neither solitary nor morose. His habits were not rigid, and he adapted easily to conditions in the field. Brown clearly possessed a sense of humor; in fact, he once tried to win the open support of the Rev. Theodore Parker by writing to him in a comic Irish brogue!

Brown’s medical history explains much that has been mistaken for mental illness in his record. Like others in his family, Brown suffered from repeated bouts with “fever and ague”—malaria—and was often bedridden during his last years. Yet even when he had to travel prone in the bed of a wagon, his energy drained by the illness, he never despaired of his project.

The “terrible gathering in my head” of which he complained for several weeks, and which some writers have mistaken as evidence of mental illness, proves to have been a prolonged infection in his sinuses and ear.

Even after staying awake two nights in succession during the raid, Brown was able to respond for more than an hour to questions from authorities. With Senator Mason and Governor Wise leading this questioning, he knew his raid had not altogether failed to win an audience. He also managed to fashion brief speeches for the assembled correspondents.

His apparent elation at his questioning was due in part to their presence; he knew he would reach readers of the “penny dailies” who were sympathetic to the cause. His war on slavery had long been in part a propaganda campaign in what were called the “prints.”

But what about the record of mental illness in Brown’s family? A number of John Brown’s maternal relations were at times committed to mental asylums, but we do not know what illnesses they may have suffered from. The youngest son of Brown’s first marriage, Frederick, began in his late teens to suffer frequent episodes of a mood disorder sufficiently severe that his father took him to a “celebrated” physician for treatment; Frederick was never institutionalized, but the family kept him indoors when his “spells” became severe.

Brown’s eldest son, John Jr., suffered a psychotic episode in Kansas. He too did not receive treatment, and for more than a year his illness resulted in symptoms like those we associate today with post-traumatic stress disorder. John Jr. later attributed the episode to the strain of losing command of his militia company after the Pottawatomie killings, in which he had no hand, and to his being arrested and held in chains for “treason” by the territorial authorities as a free-state legislator. John Jr. went on to fight in the Union Army during the war.

We also know that late in life, Brown’s eldest daughter, Ruth, experienced major depression that lasted for nearly a decade.

Altogether, these illnesses suggest that perhaps either John or Dianthe carried a hereditary predisposition to affective disorder. Yet before Brown’s Harpers Ferry raid no one in his wide circle of friends and relations ever suggested that he ought to be committed or to commit himself for treatment at a county institution or to seek the help of an “alienist.”

If friends and former associates petitioned the court for commutation of his death sentence after the raid, their affidavits (now located in the Wise Collection at the Library of Congress) show at best a range of “symptoms” far short of modern diagnostic standards for a major psychiatric disorder.

To be sure, Brown became excited when acquaintances in Ohio made light of slavery or suggested that time would eventually eradicate it. He was pledged to destroy slavery, and indifference to it deeply offended him. But at the time when several of the affiants reported such “agitated” incidents, Brown had recently sought them out to raise money for his war against slavery. He was then traveling with heavily armed young “volunteer regulars.”

He had recently left Kansas, where he had fought in a number of skirmishes and won celebrity as a champion of the free-state cause. In that context, much of what the affiants attested lost its punch.

No one ever suggested that Brown’s anger or high-decibel talk went on for long. If Brown suffered from undiagnosed mental illness in that era before the rise of psychiatry, he displayed few signs or symptoms that modern psychiatrists could identify as being linked to mental disorder.

Was it right, then, to carry the “war into Africa”? The men who petitioned the Virginia court to have Brown committed insisted he must be mad to have been raising a force to resume the fighting that had torn up Kansas. To admit otherwise was to concede that for rational people the sin of slavery might be great enough to override lifelong understandings about the rule of law, tolerance for differing opinions, the efficacy of democratic processes and the immorality of killing. If Brown was perfectly sane, conscientious men and women had to consider and perhaps reassess their own values. Was the perpetual bondage of millions of greater importance than the lives of slave owners and their allies?

Harpers Ferry answered that question in the affirmative. Implicitly it presupposed a hierarchy of values that, if widely adopted, would threaten the end of the slave regime. In a sense, then, Brown’s contribution to history was at a minimum to make righteous violence in the name of freeing the slaves thinkable for many who might not otherwise have considered the question.

Thus Brown’s life—and his self-fashioned “martyrdom”—were a rebuke not only to his reluctant contemporaries but also to revisionist historians who deny that antebellum Americans felt the moral urgency of ending slavery sufficiently to kill over it. To “get right” with Old John Brown is to accept righteous violence as intrinsic to our heritage.

Robert E. McGlone, an associate professor of history at the University of Hawaii, has studied John Brown for decades. That research led to his new biography, John Brown’s War Against Slavery, published by Cambridge University Press in July 2009.

Moonlight March

John Brown’s Moonlight March

By Tim Rowland

On a chill foggy autumn evening in 1859, abolitionist John Brown and a rough gang of 21 men with guns and pikes and revolt in their hearts quietly hiked five miles from a farm in Western Maryland to the federal armory in Harpers Ferry, Va. Their ambitions were outrageous: surprise the guards at the armory, capture wagonloads of rifles and then flee, distributing the guns among slaves. Brown hoped for nothing less than a full uprising of servant against master.

He had spent four months living on the farm simply trying to fit in. The hike to Harpers Ferry had become routine. A new beard and a shock of Lyle Lovett hair kept

locals from recognizing him as the devil who had massacred slave owners in Kansas three years before. Soon the disguise would be irrelevant. “Men, get on your arms,” he famously declared on the night of October 16, “we will proceed to the Ferry.”

Now, 150 years later, walking in Brown’s footsteps remains an eerily timeless experience. Roads that were dirt are now paved, the bridge Brown used to cross the Potomac River has been replaced, and buildings in Harpers Ferry throw off electric light. But most of the route remains pitch-black after sunset; trees that witnessed that night are still there, and woodstoves continue to scent the air.

Civil War buffs have been making this pilgrimage for better than three decades. In 1979—the 120th anniversary of John Brown’s raid—National Park Service historian Dennis Frye and 20 re-enactors, decked out in period clothing and shouldering period weapons, hiked from the Kennedy Farm in Washington County to the Harpers Ferry armory. They read from 1850s newspapers to get into character.

“We tried to transport ourselves back in time,” Frye said. “It was very respectful.”

Perhaps the most memorable part of the trek occurred midway, when an approaching car flashed its high beams and slowed. The lights belonged to a squad car from the Washington County Sheriff’s Department. Staying in character, the soldiers sauntered on—there were no squad cars in 1859. Once past, the deputy turned around and re-approached at the same slow speed, high beams blazing. As he neared, “I expected the red and blue lights to come on,” Frye said.

Instead, the deputy drew even with the procession, took one last gander, and then peeled out at full speed, apparently wanting no part of the apparition.

Unlike those earlier cultish marches, the hike planned for this fall’s 150th anniversary will be publicized and well attended. Organizers expect hundreds of enthusiasts.

The path is mostly downhill to the Potomac and flat after that, as the road hugs the riverbank on its way downstream to the confluence with the Shenandoah River. The relative ease of the hike will not diminish the experience. “It’s still sparsely settled,” Frye said, “and still quite dark”—as dark as when John Brown hitched up his team, shouted words of encouragement and set off on a mission to change the world.

“It’s been debated over the last century and a half when the Civil War began,” Frye said. “The conventional wisdom says Fort Sumter. I disagree with that. John Brown invoked a fear that communities had not experienced before.”

Brown intended to raid the federal armory and use the weapons to establish a series of forts where fleeing slaves could join his army of marauders. At a time when the going rate for an 18-year-old male slave was $1,200, a plantation that lost most of its slaves would be equivalent to a modern farm stripped of all its tractors, harvesters, plows and irrigation equipment. Further, Brown hoped that a slave rebellion in the midst of the harvest season would damage plantations even more.

The Maryland staging area for this ambitious plan was a small, two-story farmhouse that Brown rented under the name of Isaac Smith. The most notable feature is a small attic where 20 men lived in a room the size of a garage. “It must have been hotter than the hinges of hell up there,” said local historian Tom Clemens. “That’s commitment.”

Staying out of sight was essential. Brown pretended to be a humble prospector. If any of his neighbors thought it curious that there wasn’t anything worth prospecting in that neck of the woods, or that any self-respecting prospector had already been lured west, they kept their suspicions to themselves.

The prospector story was good cover for crates of pikes and guns that could be explained away as mining tools. Clemens said the blacks in Brown’s band were armed with pikes until they could be taught how to use firearms. Brown used his daughter and daughter-in-law to add to the delusion. To all eyes, Brown was what he said he was: a good family man scratching out a living from the land.

In 1859, Harpers Ferry was “a bustling industrial town of 3,000,” Clemens said. It remains unbelievably scenic, carved out of cliffs that put the squeeze on the gushing Potomac and Shenandoah rivers. Today, people from Baltimore and Washington, D.C., drive for an hour to picnic on the shore, rafters and kayakers pirouette through challenging rapids, and fishermen hope for bass, but often reel in carp.

The lower town is one of the National Park Service’s better accomplishments. Subtract the tourist with the Hawaiian shirt, and it’s easy to be transported back in time, among restored buildings, period actors and cobblestone streets. The fire engine house Brown used as a refuge during his raid, now in its fourth location, is neatly preserved, mostly. In 1892, it was disassembled, transported to the Chicago World’s Fair, reassembled, disassembled and reassembled in Harpers Ferry as a mirror image of itself; tradesmen based their work on a photographic impression that was a negative.

One of the many floods that have ravaged Harpers Ferry since the raid washed away the bridge John Brown crossed to enter the town. In its place today is a high pedestrian bridge that accommodates Appalachian Trail hikers.

Fifteen decades ago, Harpers Ferry had one of two national armories, yet there was no militia garrisoned on site because no one anticipated a raid, much less a war. The night Brown arrived, weapons were guarded only by a snoozing night watchman. A baggage man for the B&O railroad named Hayward Shepherd proved more problematic.

When Shepherd saw a band of armed men trundling across the bridge into town at 1:30 a.m., he apparently thought they were bandits planning to rob the mail train from Wheeling. Shepherd hustled up the tracks to flag it down. In the darkness, Brown’s men couldn’t have known Shepherd was a free black man. They leveled their guns and fired.

A century and a half later, some historians speculate that Shepherd was in on the raid but got cold feet. And some suggest he was asked to join in, but refused. Arguments have led to what Clemens called Harpers Ferry’s “dueling monuments.”

In 1931 the United Daughters of the Confederacy and Sons of Confederate Veterans dedicated a monument to Shepherd, celebrating him as a black man who did not flee or take up arms against whites. But purported racists objected that blacks deserved no recognition in history, let alone a monument.

For decades, however, prominent African-Americans—including W.E.B. DuBois—have objected to the notion that Shepherd be revered for an ambivalence, real or imagined, toward slavery.

The monument was removed from display during a park construction project in the mid-1970s. And as opposing factions quibbled over whether it should be returned, “for years the monument sat in a warehouse with a tarp over it,” Clemens said. It was returned to its location in 1981, but was covered up until 1995, when the park service added a plaque to explain everything.

Back on the bridge, Brown and his men stopped the train, then let it steam off down the tracks. A reasonable person might consider that Brown should have focused on seizing the armory’s guns and getting out of town before releasing the train.

Instead Brown lingered—shooting at townsfolk, taking prisoners and raising hell—knowing trouble would be on the way as soon as the B&O reached its next stop. Perhaps Brown was truly daft. Perhaps he wanted to be captured, despite the obvious penalties.

“That’s the critical question,” Clemens observed. “Is he crazy, or is he a shrewd manipulator of public opinion?” Brown had a family history of mental infirmities, yet Clemens thinks “it’s too easy to write him off as crazy.”

Frye believes Brown must have realized that if he held the train, people at the next station would come to investigate. Whether he held the train or not made no difference…word would get out either way. Besides, Brown’s plan was too involved to be fulfilled with one small, deadly statement. Brown believed he was “a man of God, called by God to rid the nation of slavery,” Frye said. So he stayed put, the consequences be damned.

Brown’s true undoing, however, had little to do with the train: It was trying to save Shepherd. Gunshots had awakened physician John Starry, who ran out to see what the commotion was about.

Taking advantage, Brown hurried the doctor to the porter’s side. After Starry pronounced the wounds fatal, Brown let him go.

“Starry is the Paul Revere of Harpers Ferry,” Frye said. The doctor threw himself onto his horse and headed for the militia in Charles Town, seven miles away.

The militia kept Brown corralled until Col. Robert E. Lee arrived to break down the door of the fire engine house where Brown and his raiders had holed up. Ten, including two of his sons, were killed. Six were captured and five escaped. The raiders killed four—including Harpers Ferry Mayor Fontaine Beckham—and wounded nine. Within days Brown was charged with treason for taking up arms against Virginia.

Brown’s attorneys begged him to plead insanity to avoid the gallows. But Brown worried that if he were declared insane his cause might be seen that way as well. With little defense to offer, Brown was convicted by a jury on November 2, and hanged on December 2.

Although slaves did not revolt because of Brown’s actions, the effect on the rest of the population was immense. “The fear that gripped the country after that October was like the fear that gripped America after September 11,” Frye said. “Before, people avoided talking about slavery; after John Brown, no one stopped talking about it.”

Brown had appeared to be an everyman on his rented farm. In the South, people began to look at every nearby everyman and wonder. In 1860, there were 5 million whites and 4 million slaves in the South. Might that quiet, pleasant next-door neighbor be planning a revolt?

“He was living among people under an assumed name under peaceful circumstances. It was every slaveholder’s nightmare,” Clemens said.

In the North, people were against slavery in theory, but still largely racist. The thought of millions of slaves roaming the streets as free men and women competing for jobs was frightening.

Following his execution, Brown was buried near a small farm he owned in Lake Placid, N.Y. A hapless preacher from Vermont presided at Brown’s funeral. His parishioners did not see it as the Christian thing to do; soon he was out of a job.

Abolitionists remained a fringe group, yet Brown’s attack on Harpers Ferry was eventually seen, at least in the North, as the exploit of a martyr, and even a hero.

Newspaper columnist and history junkie Tim Rowland loves to hike, but supports his habits by writing. His latest book, Maryland’s Appalachian Highlands: Massacres, Moonshine and Mountaineering, was released by The History Press in June.

Review

John Brown’s Blood Oath

Author Tony Horwitz (Confederates in the Attic) returns to one of his favorite subjects, the Civil War, in his forthcoming book, Midnight Rising: John Brown and the Raid That Sparked the Civil War. It’s a history that doubles as a character study of a radical whose act of terror carries overtones of 9/11. “Harpers Ferry seems an al-Qaeda prequel: a long-bearded fundamentalist, consumed by hatred of the U.S. government, launches 19 men in a suicidal strike on a symbol of American power,” Horwitz writes. “A shocked nation plunges into war.”

The excerpt below traces Brown’s first campaigns of war and terror, three years before Harpers Ferry, when he and his family formed a Northern army to fight proslavery forces in Kansas.

* * * *

At about 11 o’clock on the brightly moonlit night of May 24, 1856, James Doyle, his wife, Mahala, and their five children were in bed when they heard a noise in the yard. Then came a rap at the door of their cabin on Mosquito Creek, a tributary of Pottawatomie Creek. A voice outside asked the way to a neighbor’s home. When Doyle opened the door, several men burst in, armed with pistols and large knives. They said they were from the “Northern army” and had come to take Doyle and three of his sons prisoner.

The Doyles, a poor family from Tennessee, owned no slaves. But since moving to Kansas the preceding autumn, James and his two oldest sons had joined a proslavery party and strongly supported the Southern cause. Two of the Doyles had served on the court convened the month before at Dutch Henry’s Crossing on the Pottawatomie to charge the Browns with violating proslavery laws.

Mahala Doyle pleaded tearfully with the intruders to release their youngest captive, her 16-year-old son, John. They let him go and then led the others out of the cabin and into the night. “My husband and two boys, my sons, did not come back,” Mahala later testified. She and John didn’t know the identity of the men who came to their door, but they’d glimpsed their faces in the candlelight. “An old man commanded the party,” John Doyle testified. “His face was slim.” He added: “These men talked exactly like Eastern men and Northern men talk.”

Before leaving, the strangers asked the Doyles about a neighbor, Allen Wilkinson, who lived about half a mile away with his wife, Louisa Jane, and two children. Like Doyle, Wilkinson had come from Tennessee and owned no slaves. Unlike Doyle, Wilkinson could read and write. He was a member of Kansas’s proslavery legislature, and his cabin served as the local post office.

After midnight, Louisa Jane, who was sick with measles, heard a dog barking and woke her husband. He said it was nothing and went back to sleep. Then the dog began barking furiously and Louisa Jane heard footsteps and a knock. She woke her husband again; he called out, asking who was there.

“I want you to tell me the way to Dutch Henry’s,” a voice replied. When Wilkinson began to give directions, the man said, “Come out and show us.” His wife wouldn’t let him. The stranger then asked if Wilkinson was an opponent of the Free State cause. “I am,” he said.

“You are our prisoner,” came the reply. Four armed men poured into the cabin, took Wilkinson’s gun, and told him to get dressed. Louisa Jane begged the men to let her husband stay: She was sick and helpless, with two small children.

“You have neighbors?” asked an older man who appeared to be in command. He wore soiled clothes and a straw hat pulled down over his narrow face. Louisa Jane told him she had neighbors, but couldn’t go for them. “It matters not,” he said. Unshod, her husband was led outside. Louisa Jane thought she heard her husband’s voice a moment later “in complaint,” but then all was still.

Dutch Henry’s Crossing was named for Henry Sherman, a German immigrant who had settled the ford. He traded cattle to westward pioneers and ran a tavern and store that served as a gathering place for proslavery men. He and his brother, William, were feared by Free State families for their drunkenness and threatening behavior.

On the night of the Northern army’s visit to the Pottawatomie, Dutch Henry was out on the prairie looking for stray cattle. But one of his employees who lived at the Crossing, James Harris, was asleep with his wife and child when men burst in carrying swords and revolvers. They demanded the surrender of Harris and three other men who were spending the night in his one-room cabin. Two were travelers who had come to buy a cow; the third was Dutch Henry’s brother, William.

Harris and the two travelers were questioned individually outside the cabin, and then returned inside, having been found innocent of aiding the proslavery cause. Then William Sherman was escorted from the cabin. About 15 minutes later, Harris heard a pistol shot; the men who had been guarding him left, having taken a horse, a saddle, and weapons. It was now Sunday morning, about 2 or 3 a.m. The terrified settlers along the Pottawatomie waited until dawn to venture outside. At the Doyles’, the first house visited in the night, 16-year-old John found his father, James, and his oldest brother, 22-year-old William, lying dead in the road about 200 yards from their cabin.

Both men had multiple wounds; William’s head was cut open and his jaw and side slashed. John found his other brother, 20-year-old Drury, lying dead nearby.

“His fingers were cut off, and his arms were cut off,” John said in an affidavit. “His head was cut open; there was a hole in his breast.” Mahala Doyle, having glanced at the bodies of her husband and older son, could not look at Drury. “I was so much overcome that I went to the house,” she said.

Down the creek, locals who went to the Wilkinsons’ cabin to collect their mail found Louisa Jane Wilkinson in tears. She had heard about the Doyles and could not bring herself to go outside, for fear of what she might find. Neighbors discovered Allen Wilkinson lying dead in brush about 150 yards from the cabin, his head and side gashed, his throat cut.

At Dutch Henry’s Crossing, James Harris had also gone looking for his overnight guest, William Sherman. He found him lying in the creek.

“Sherman’s skull was split open in two places and some of his brains was washed out by the water,” Harris testified. “A large hole was cut in his breast, and his left hand was cut off except a little piece of skin on one side.”

News of the murders along the Pottawatomie spread quickly through the district. A day after the killings, John Brown was confronted by his son Jason. A gentle man known as the “tenderfoot” of the Brown clan, Jason had stayed behind with his brother John Junior while the others headed to Dutch Henry’s.

“Did you have anything to do with the killing of those men on the Pottawatomie?” Jason demanded of his father.

“I did not do it, but I approved of it,” Brown answered.

“I think it was an uncalled for, wicked act,” Jason said.

“God is my judge,” his father replied. “We were justified under the circumstances.”

This was about as clear a statement as Brown would ever make about what became known as the Pottawatomie Massacre. He spoke of it rarely, and then only in vague terms that suggested he was culpable without having personally shed any blood. His family hewed to this line. “Father never had any thing to do with the killing but he run the whole business,” said Salmon, the most talkative of the four sons at the massacre. “The work was so hot, and so absorbing, that I did not at the time know where each actor was, exactly, or exactly what each man was doing.”

The Browns and their allies cast the killings as an act of self-defense: a preemptive strike against proslavery zealots who had threatened their Free State neighbors and intended to harm them. The Browns’ defenders also denied any intent on their part to mutilate the Kansans. Broadswords had been used to avoid making noise and raising an alarm; the gruesome wounds resulted from the victims’ attempts to ward off sword blows.

But this version of events didn’t accord with evidence gathered after the killings. Mahala Doyle and James Harris both testified that they heard shots in the night. And “old man Doyle” was found with a bullet hole in his forehead, to go with a stab wound to his chest.

The most plausible account of Brown’s actions came from a family member who wasn’t there: John Junior. Though initially opposed to his father’s mission, he later wrote a lengthy defense of it. Until late May 1856, proslavery forces in Kansas had committed almost all the violence, killing six Free State men without reprisal. As the Browns and their Free State allies stewed, John Junior said, they realized the enemy needed shock treatment—“death for death.”

But the Pottawatomie attack wasn’t simply a matter of evening the score in Kansas. Those sentenced to die must be slain “in such manner as should be likely to cause a restraining fear,” John Junior wrote. In other words, the killing should so terrorize the proslavery camp as to deter future violence.

In this light, the massacre made grisly sense. Like Nat Turner, the most haunting figure in Southern imagination, Brown came in the night and, with his Northern army, dragged whites from their beds, hacking open heads and lopping off limbs. The killers wore no masks, plainly stated their allegiance, and left maimed victims lying in the road or creek. Pottawatomie was, in essence, a public execution, and the message it sent was chilling.

“I left for fear of my life,” Louisa Jane Wilkinson testified in Missouri, where she took refuge after her husband’s killing. The Doyles also fled a day after the slaughter.

So did many of their neighbors. And news that five proslavery men had been, as one settler said, “taken from their beds and almost litterly heived to peices with broad swords,” spread like prairie fire across Kansas. “I never lie down without taking the precaution to fasten my door,” a settler from South Carolina wrote his sister soon after the killings. “I have my rifle, revolver, and old home-stocked pistol where I can lay my hand on them in an instant, besides a hatchet & axe. I take this precaution to guard against the midnight attacks of the Abolitionists, who never make an attack in open daylight.”

Pottawatomie had clearly succeeded in sowing terror. But it failed to produce the “restraining fear” that John Junior believed to be its intent. Instead of deterring violence, the massacre incited it.

LET SLIP THE DOGS OF WAR! read the headline in a Missouri border paper, reporting on the deaths. Up to that point, the Kansas conflict had generated a great deal of heat but relatively little bloodshed. Now, in a single stroke, Brown had almost doubled the body count and whipped up his already rabid foes, who needed little spur to violence.

Not for the last time, Brown acted as an accelerant, igniting a much broader and bloodier conflict than had flared before. “He wanted to hurry up the fight, always,” Salmon Brown observed of his father. “We struck merely to begin the fight that we saw was being forced upon us.”

The number of killings escalated dramatically in the months that followed, earning the territory the nickname “Bleeding Kansas.” In early June, 10 days after Pottawatomie, Brown struck again, joining his band with other Free State fighters in a bold dawn attack on a much larger force of proslavery men. This marked the first open-field combat in Kansas, and the first instance of organized units of white men fighting over slavery, five years before the Civil War. The Battle of Black Jack, as it became known, was a confused half-day clash involving about a hundred combatants. It ended with the surrender of the proslavery men, who were fooled into believing they were outnumbered. “I went to take Old Brown, and Old Brown took me,” the proslavery commander later conceded. He surrendered not only his men but also a valuable store of guns, horses, and provisions.

Black Jack also brought greater attention to Brown, who kept the Northern press abreast of his campaign, sometimes taking antislavery journalists with him in the field. One of these was William Phillips, a New York Tribune correspondent who rode with Brown after the battle. “He is not a man to be trifled with,” Phillips wrote, “and there is no one for whom the border ruffians entertain a more wholesome dread than Captain Brown.”

“He is a strange, resolute, repulsive, iron-willed inexorable old man,” Phillips added, possessing “a fiery nature and a cold temper, and a cool head—a volcano beneath a covering of snow.”

Brown’s growing renown came at great cost to his family. His son-in-law, Henry Thompson, was shot in the side at Black Jack, and 19-year-old Salmon Brown sustained a gunshot to the shoulder soon after the battle. Life on the run, subsisting on gooseberries, bran flour, and creek water flavored with a little molasses and ginger, wore down the outlaw band. “We have, like David of old, had our dwelling with the serpents of the rocks and wild beasts of the wilderness,” Brown wrote his wife in June. Three of his sons became so debilitated by illness that in August he escorted them to Nebraska to recover in safety.

By then, conflict raged across eastern Kansas. Partisans on both sides spent the summer raiding, robbing, burning, and murdering, while federal troops struggled to contain the anarchy. The violence climaxed in late August, when several hundred proslavery fighters, armed with cannons, descended on the Free State settlement at Osawatomie, where Brown’s sister and other family members lived. With just 40 men, Brown led a spirited defense of Osawatomie. Though he was ultimately forced to retreat, Brown scored another propaganda victory by fearlessly battling a much larger and better-armed foe.

“This has proven most unmistakably that ‘Yankees’ will fight,” John Junior wrote of the reaction to Osawatomie. His father, slightly wounded in the combat, was initially reported dead, a mistake that only enhanced his aura. The battle also gave the Captain a new title. As a noted guerrilla and wanted man, he would adopt a number of aliases over the next three years. But the nom de guerre that stuck in public imagination was “Osawatomie Brown,” a tribute to his Kansas stand.

The name also evoked his family’s continued sacrifice in the cause of freedom. Early in the morning before the battle at Osawatomie, proslavery scouts riding into the settlement encountered Frederick Brown on his way to feed horses. Believing himself on friendly ground, Frederick evidently identified himself to the riders. One of them was a proslavery preacher who blamed the Browns for attacks on his property, and he replied by shooting Frederick in the chest. The 25-year-old died in the road.

His father learned of the slaying while rallying his small force to repel Osawatomie’s invaders. Frederick’s older brother Jason took part in the battle, and at its end, he stood with his father on the bank of the Osage River, watching smoke and flames rise in the distance as their foes torched the Free State settlement they’d fought so hard to defend.

“God sees it,” Brown told Jason. “I will die fighting for this cause.” He had made similar pledges before. But this time Brown was in tears, and he mentioned a new field of battle to his son.

“I will carry the war into Africa,” he said. This cryptic phrase spoke clearly to Jason, who knew “Africa” was his father’s code for the slaveholding South.

Excerpted from Midnight Rising: John Brown and the Raid That Sparked the Civil War, by Tony Horwitz. Copyright © 2011 by Tony Horwitz. Reprinted by arrangement with Henry Holt and Company, LLC. All rights reserved.