[divider_flat]On the eve of Sharpsburg, Uncle Robert broke down when the tough Texan refused to apologize to Shanks Evans

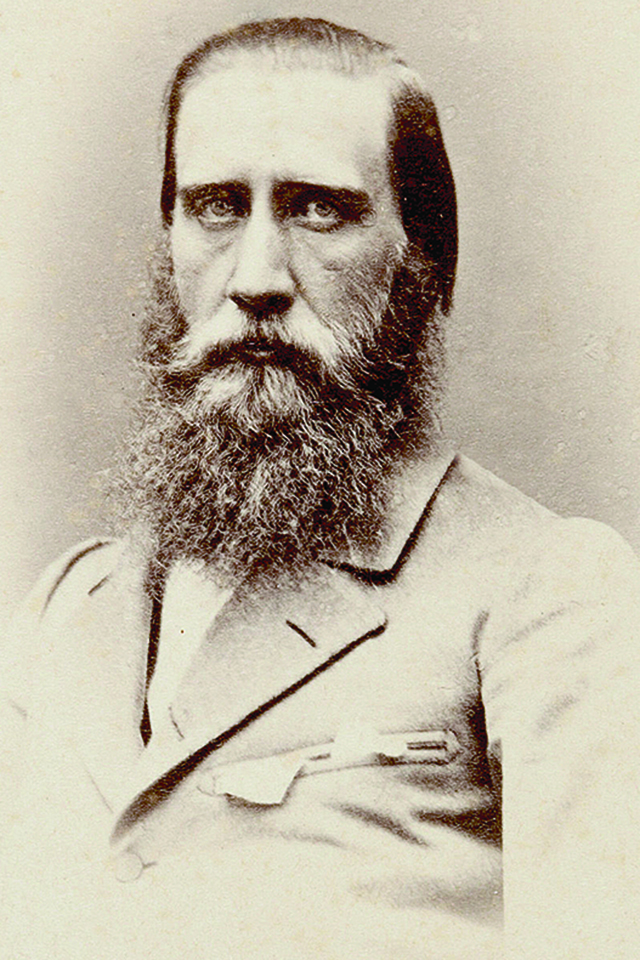

[divider_flat]WHEN THE CIVIL WAR BEGAN in April 1861, Richard Watson York was a 21-year-old schoolmaster living near Raleigh, N.C. He had already organized his students into a militia troop, which became Company I of the 6th North Carolina Infantry in May and served all four years in what became known as the Army of Northern Virginia. After the war, “Watt” York—the 6th’s first captain—wrote occasional articles about the regiment and what he had seen while serving. One of those appeared in 1875 in the magazine Our Living and Our Dead—“Gen. Hood’s Release From Arrest: An Incident of the Battle of Boonesboro”—and recounts an occurrence that has somehow escaped many historians’ attention over the years.

At the Second Battle of Manassas in August 1862, the 6th North Carolina fought in Colonel Evander A. Law’s Brigade, part of Brig. Gen. John Bell Hood’s Division. On August 30, the battle’s final day, Hood’s commander, Maj. Gen. James Longstreet, positioned nearly 20,000 men—five divisions in all—for a crushing onslaught on the Union army’s left flank. Longstreet chose Hood’s Texas Brigade to be the “column of direction” for the entire force.

The ball opened about 4 p.m. with a ruthless attack by Hood on the 5th New York Infantry (Duryée’s Zouaves). In roughly 10 minutes, the stunned Zouaves had been all but destroyed, the survivors fleeing desperately.

As Hood’s men pursued the overwhelmed Federals up Chinn Ridge, the general called for help from Brig. Gen. Nathan G. “Shanks” Evans, positioned to his right. Unrelenting Confederate pressure finally succeeded in driving the Yankees from the ridge by 6 p.m., but Hood’s and Evans’ troops were understandably depleted, scattered, and exhausted. They took no part in the final action of the day—Longstreet’s effort to take Henry Hill, where Army of Virginia commander Maj. Gen. John Pope had hastily assembled a defensive line.

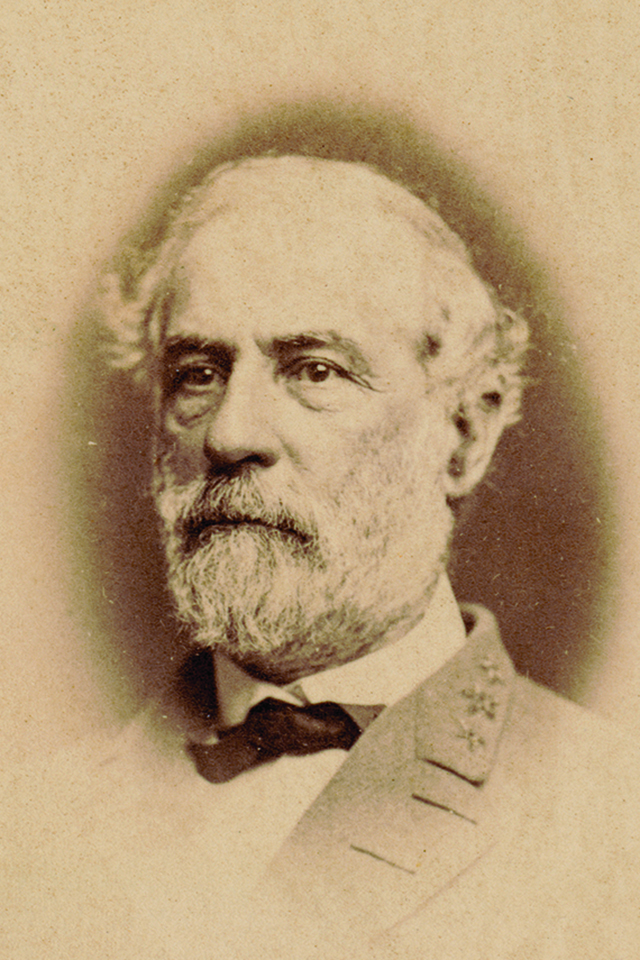

That night, Hood delivered a dispatch to General Robert E. Lee at his Army of Northern Virginia headquarters. Hood and Lee had met six years earlier during their cavalry service in Texas; Lee gave Hood his first Confederate field assignment, on the Virginia Peninsula, in May 1861; and Lee had repeatedly commended Hood’s combat leadership, most recently his troops’ effort at the Battle of Gaines’ Mill on June 27, 1862.

Hood recalled in his memoir, Advance and Retreat, that Lee “met me in his usual manner, and asked what had become of the enemy.” Responded Hood: “[I]t was a beautiful sight to see our little battle flags dancing after the Federals as they ran in full retreat,” to which Lee replied, “God forbid I should ever live to see our colors moving in the opposite direction!”

Hood, however, soon found himself in hot water. Late on August 30, he had come upon several brand-new Federal ambulances on his front and had sent forward some of his Texans to capture those wagons—fine battlefield trophies that he distributed among his regiments. The next day, though, Evans ordered Hood to turn the ambulances over to his own brigade. By seniority, Evans outranked Hood and was therefore his superior on that part of the field.

It should be no surprise that Hood refused the directive. “Whereas I would cheerfully have obeyed directions to deliver them to General Lee’s Quarter Master,” he later explained, “I did not consider it just that I should be required to yield them to another brigade of the division, which was in no manner entitled to them.”

Evans reported the matter to Longstreet, who placed Hood under arrest and ordered him to Culpeper Court House for court-martial proceedings. As Hood remembered, “General Lee…became apprised of the matter, and at once sent instructions that I should remain with my command, though he did not release me from arrest.”

Lee’s gesture mollified Hood, but not his men, who “became half mutinous in their resentment,” according to historian Douglas Southall Freeman.

Heavy rain on August 31 hindered Lee’s prospects in pursuing Pope’s beaten army, which had fallen back to its fortifications around Centreville. Lee, in poncho and rubber overalls, was standing alongside Traveller when someone yelled, “Yankee cavalry!” The alarm proved false, but the startled horse reared. Lee grabbed at the reins but tripped in his rain gear and fell hard on his hands. He broke a bone in his right wrist and badly sprained his left. Unable to hold the reins, the injured general was confined to an ambulance for the next few days.

On September 1, Jackson’s troops contested the Federals at the Battle of Ox Hill (Chantilly). It was a sharp little battle, fought amid a fierce thunderstorm, that ended up costing the Army of the Potomac dearly, with the deaths of Maj. Gens. Isaac Stevens and Philip Kearny—the highest-ranking Northern officers yet to die in combat.

His army now 30 miles from Washington, Lee sorted through his options. Pope was relieved of his command days after the Manassas fighting and his troops were merged into Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac. Lee knew that the enemy, though dispirited, remained numerically strong and could not be attacked in their works. Lee also knew he couldn’t stay put, waiting for a point when the dreadfully cautious McClellan might come out looking for battle.

“The present seems to be the most propitious time since the commencement of the war for the Confederate Army to enter Maryland,” Lee wrote President Jefferson Davis on September 3. Virginia had been largely cleared of Federal forces, and Richmond was safe. On the other hand, his men lacked shoes, and his army’s transportation service was feeble. “We cannot afford to be idle,” he insisted, “and though weaker than our opponents in men and military equipments, must endeavor to harass if we cannot destroy them.”

Davis did not object.

As the Rebels moved toward Maryland on September 4, Hood was with his troops, but not leading them—riding at the rear of the column on his prized horse, Jeff Davis. One evening, as members of the Texas Brigade marched past Lee in Leesburg, Va., they cried out, “Give us Hood! General Lee, give us Hood!” Lee was moved. Raising his hat, he answered, “You shall have him, gentlemen!”

Hood and his men crossed the Potomac at White’s Ford on September 6 and turned north toward Frederick. At one point, Shanks Evans ordered Hood’s Texans to wade across the Monocacy River, but they balked, making it clear they would obey no orders save those issued by Hood. (As the general later put it, “My division had become restive and somewhat inclined to insubordination on account of my suspension.”) Hood eventually came up and signaled them to cross.

The Confederate army tarried about Frederick for several days, drawing unflattering comments from a few of the locals. Dr. Lewis H. Steiner, an inspector for the U.S. Sanitary Commission, happened to be in town during the Confederate occupation. He kept a diary from September 5 to 13, exaggerating in a September 10 entry the size of Maj. Gen. Stonewall Jackson’s corps as 64,000.

On September 9, as Lee began devising his plans, the army’s cavalry commander, Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart, reported that McClellan was slowly advancing north from Washington and was about 25 miles from Frederick. That afternoon, Lee informed Longstreet and Jackson that the Federals’ Harpers Ferry and Martinsburg garrisons—threats to Lee’s lines of supply and communication—hadn’t yet been evacuated, as he had expected. That had to be dealt with.

Lee ordered his army split as follows:

1. Jackson was to make a circuitous march, “capture such of them as may be at Martinsburg,” then approach Harpers Ferry from the south, to Bolivar Heights.

2. Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws was to occupy Maryland Heights, across the river from the arsenal town, “and by Friday morning [September 12]…endeavor to capture the enemy at Harper’s Ferry.”

3. Brig. Gen. John G. Walker’s Division would take Loudoun Heights east of town and intercept any attempt by the enemy to escape.

4. Longstreet was to march to Boonsboro, Md., roughly 15 miles northwest of Frederick.

5. Maj. Gen. D.H. Hill’s Division would follow as the army’s rear guard. After capturing the Union garrison, Jackson, McLaws, and Walker were to reunite with Longstreet and Hill at Boonsboro or nearby Hagerstown.

The Confederates began moving as ordered on the morning of September 10. After those in the Federal garrison at Martinsburg skedaddled to Harpers Ferry, Jackson marched on. His troops, as well as McLaws’ and Walker’s, were not on their respective heights until the 13th, a day behind schedule. Another day was spent readying for an assault while Confederate artillery lobbed shells at the Federal garrison. On the morning of September 15, Union commander Dixon S. Miles finally signaled his intent to surrender. Jackson had captured a larger army—12,520 officers and men, plus 73 cannons and 12,000 small arms—than anyone expected.

McClellan reached Frederick on the morning of September 13 and soon received an astronomical break when an Indiana regiment in Maj. Gen. Joseph Mansfield’s 12th Corps found a copy of Lee’s orders in a field wrapped around three cigars. It was Special Orders No. 191, the detailed marching orders, troop dispositions, and multiday schedule of Lee’s entire army.

The paper quickly made its way into the hands of Brig. Gen. Alpheus Williams, Mansfield’s ranking subordinate, at corps headquarters. By luck, Williams’ aide, 1st Lt. Samuel Pittman, was able to vouch for the authenticity of the orders because they had been written and signed by Colonel Robert H. Chilton, whom Pittman had served with prewar. Pittman even recalled Chilton’s handwriting!

Williams rushed the document straight to McClellan with the note: “I enclose a Special Order of Gen. Lee commanding Rebel forces which was found on the field where my corps is encamped.” “It is a document of interest,” he wrote with considerable understatement, “& is also thought genuine.”

In his campaign report, the general noted that this copy of Lee’s orders had been addressed to “Maj. Gen. D.H. Hill, Commanding Division.” Chilton had actually made copies for all the Army of Northern Virginia division commanders. It seems Hill never realized the loss. Technically under the command of Jackson in Maryland, he had had the orders transcribed for him by Stonewall himself. (Hill kept that transcription to his dying day.)

Writing about the incident well after the war, Colonel Walter Taylor, of Lee’s staff, probably put it best: “The God of battles alone knows what would have occurred but for the singular accident.”

When exactly did Lee learn that McClellan possessed his orders, however? The Union commander was entertaining visitors on the morning of the 13th when word of his good fortune arrived by courier. One of McClellan’s visitors happened to be a Southern sympathizer who was able to divine what had happened. Later that day, he got word to J.E.B. Stuart, who in turn informed Lee.

“I have all the plans of the rebels,” McClellan wrote President Abraham Lincoln at noon that day, “and will catch them in their own trap if my men are equal to their emergency.”

Or, rather, if he were “equal to the emergency,” for McClellan began to squander his intelligence coup, issuing orders for his troops to start marching at daylight the next morning. Part of the problem was that the “Young Napoleon” had a very un-Napoleonic dread of the enemy army’s numerical strength, particularly because he grossly inflated it to the figure of “100,000.”

Lee had been given critical time, but the Army of Northern Virginia remained in a tight spot. Straggling had reduced its strength to some 35,000. Two-fifths of it, Jackson with three divisions, plus Walker’s Division—nearly 15,000 troops—were on the south side of the Potomac River engaged at Harpers Ferry and then dealing with the Union POWs. McLaws’ and Anderson’s divisions (8,000 total) were actually closer to advancing enemy forces than they were to Longstreet’s two divisions, which had marched on to Hagerstown rather than stop at Boonsboro.

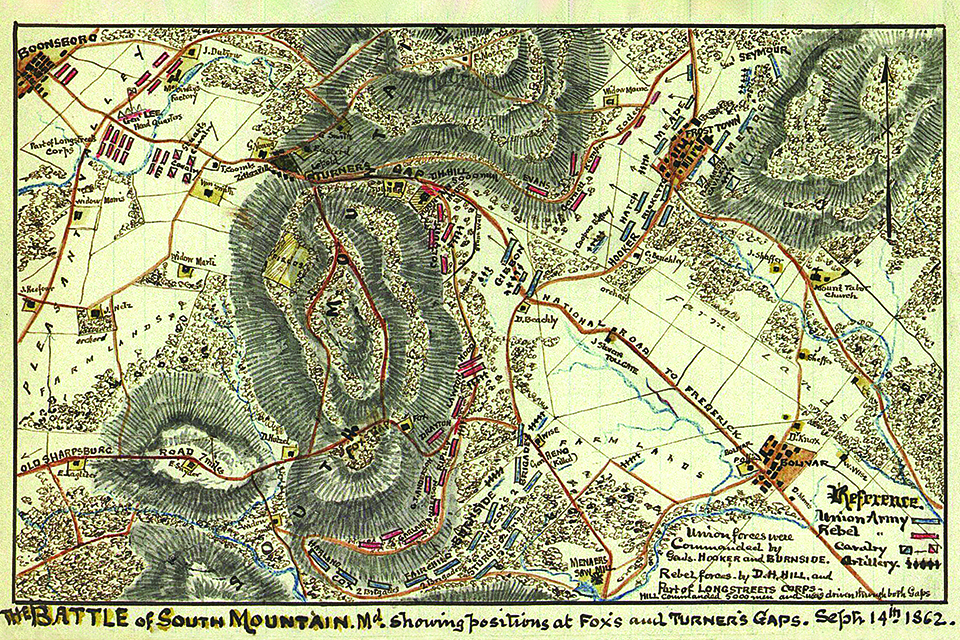

All that stood in the way of McClellan’s 87,000-strong army was Stuart’s cavalry and D.H. Hill’s Division. The Confederates at least had a topographical ally: South Mountain, a long ridge running 53 miles north of the Potomac, a dozen miles west of Frederick. If Hill’s infantry could hold the three passes that cut through the mountain, Jackson might have enough time to complete his actions at Harpers Ferry and rejoin Lee’s army.

Yet if McClellan’s forces broke through the gaps, they would pour through and get between Jackson and Longstreet, and further split the Confederates.

On September 13, Hood’s Division was with Lee and Longstreet at Hagerstown. On the morning of the 14th, the Confederates marched back to Boonsboro to help Hill hold South Mountain. Hood’s men marched fast, not so much anxious as angry that they were going into battle without their general. Recalled Corporal Joe Polley of the 4th Texas Infantry: “Feeling that the commander they most trusted was deeply wronged, the officers and men of the division had given expression to their indignation, and now as they marched toward what might be another battle, their wrath grew intense. The Texans, naturally, felt most aggrieved, and were most outspoken.” That afternoon, as the Lone Star State boys neared the mountain slope, they again shouted, “Give us Hood! Give us Hood!”

The situation was tense. Federals were attacking the Confederates at Turner’s, Fox’s, and Crampton’s gaps, hoping to break through somewhere. The outnumbered Rebels were bending, as Longstreet continued to shuttle his meager forces to the various threatened points.

Lee had already sent for Hood. “I found General Lee standing by the fence,” Hood recalled in Advance and Retreat. Dismounting, he stood before the commander.

“General,” Lee explained, “here I am just upon the eve of entering into battle, and with one of my best officers under arrest. If you will merely say that you regret this occurrence, I will release you and restore you to the command of your division.”

Hood respectfully replied that he could not do so: Evans’ demand for ambulances that his troops had not captured was an unjust affront to the courage and honor of his own men.

Lee asked again. Again Hood declined.

Wrote “Watt” York in his 1875 article: “I saw Gen. Lee standing in the fence corner to our right, dismounted, holding his gray horse by the bridle reins, and leaning against the fence, with his left hand lying upon the top rail….He was entirely alone.” York was close enough to hear their conversation after Hood rode up, dismounted, and saluted. He heard both Lee’s apology request and Hood’s rejection.

Then, according to York, the old man broke down:

Hood’s Division, tired and worn, was rapidly but silently marching by on the old national turnpike up to the gap. The big tears were rolling down Gen. Lee’s cheeks, plowing their little furrows through the dust upon his noble face. “Here I am going into an important battle,” said Gen. Lee, “and one of my best generals under arrest. Gen. Hood, can’t you somewhat apologize to Gen. Evans?”

“Never,” replied Gen. Hood. At that point, Lee gave up: “Take command of your division, Gen. Hood.”

The Texans saw Hood shake Lee’s hand, mount up, and start riding to the head of his division. Word spread quickly through the ranks. “Uncle Robert has released General Hood!” they cheered.

“Hurrah for General Lee!”

“Hurrah for General Hood!”

“Go to hell, Evans!”

Confederates managed to hold on at the South Mountain passes for a time, but Lee eventually ordered a withdrawal. On September 15, the Harpers Ferry garrison surrendered, and with Jackson’s troops soon back in the fold (minus Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill’s Division—still processing Union POWs), Lee took a defensive position behind nearby Antietam Creek. On the morning of September 17, Hood’s Division would win laurels anew by repelling the assaults of Union Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker’s 1st Corps against the Confederate left during the Battle of Sharpsburg.

After the battle, a grateful Stonewall recommended Hood for promotion to major general. Shanks Evans, on the other hand, continued to quarrel with other officers, even his superiors. Twice he was court-martialed for drunkenness, and when the war ended he was without a field command. Evans had, as Hood’s men had jeered, figuratively gone to hell.

Eight years after the war, Richard York chanced to meet Hood and sat down with him to reminisce. He brought up the incident of Lee at South Mountain, and asked Hood if he remembered it, too.

“Yes, I do,” Hood replied, “and shall as long as I remember anything.”

“He alluded feelingly to his great Commander being unable to restrain his tears,” York recalled, “and as Gen. Hood related the incident to me, the big tears came unbidden to his own eyes.”

At the age of 48, John Bell Hood died of yellow fever in New Orleans on August 30, 1879, only a few days after his wife, Anna, and eldest daughter, Lydia. He left behind 10 orphan children.

Stephen Davis, who writes from Atlanta, is the author of the forthcoming John Bell Hood: Texas Brigadier to the Fall of Atlanta (Mercer University Press, December 2019).

_____

Stuart Scuttlebutt

The story of Maj. Gen. John B. Hood receiving a wound to the arm on the second day of Gettysburg is well known. So is that of General Robert E. Lee’s unhappiness with the operations of his army’s cavalry commander, Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart, during that campaign. Not so familiar is the tale of how, in the summer of 1863, Richmonders were gossiping that Hood might be appointed to succeed Stuart as commander of the Army of Northern Virginia’s cavalry.

After Gettysburg, Hood was transported to Williamsport, Md., on the Potomac River, then borne through Winchester and Staunton, Va. From there he traveled by rail to Charlottesville, where he spent several weeks convalescing at the home of his friend, Texas Senator Louis Wigfall. He was in Richmond by August 6. John Darby, the general’s physician, who had treated his wound at Gettysburg and had thereafter accompanied him, shared rooms with Hood, noting that “use of the arm has rapidly commenced.”

In every capital city, there is much talk and gossip. After Gettysburg, people speculated as to why the battle had been lost. Stuart came in for his share of the blame, having absented himself from Lee’s army in the critical days of late June when George Gordon Meade’s Army of the Potomac was marching toward it.

Hood figured in some of the gossip. Robert G.H. Kean, a War Department official, recorded in his diary on August 9, “It is…rumored that Stuart is to be relieved of command of the cavalry of the Army of Northern Virginia and Hood put in that position.”

The scuttlebutt was founded in some fact—at least rumored fact. The Petersburg Express in the first week of August actually published an article stating that Hood had been appointed Lee’s chief of cavalry and that Stuart and Wade Hampton were reporting to him. The Richmond Dispatch mentioned the article on August 8. There is no record of Hood having taken notice of this press buzz, although he might not have been surprised. In the mid-1850s, he had served in the 2nd U.S. Cavalry under Lee, who was the regiment’s lieutenant colonel. When the Civil War broke out, Hood’s first Confederate appointment was as 1st lieutenant of cavalry. In late May 1861, Lee, leader of Virginia state forces, had sent Hood to Yorktown, where Colonel “Prince John” Magruder put him in charge of his cavalry.

On the other hand, Stuart did take note of the newspaper gossip. “I suppose you have seen mention of Hood’s assignment to the command of the Cavalry as Lt Genl,” Stuart wrote his wife, Flora, on August 11. “It is all bosh, gotten up by some malicious scamp striving to undermine and vilify me.” The next day, in another letter he commented further on the Hood rumors: “Gen Lee knows nothing of it & I believe entre nous he has recommended me already for the place.” Despite the criticism he had taken from the Gettysburg Campaign, Stuart in the summer of 1863 thought he would be promoted to lieutenant general if Lee approved designating the army’s cavalry arm as a corps.

Stuart remained hopeful. “I feel very confident that Gen’l Lee has recommended me for Lt Gen’l of Cavalry,” he wrote Flora on the 18th. “The newspaper talk on the subject is an effort (which I believe will fail) to manufacture public opinion in favor of Hood.” “The L.G. is still in suspense,” he wrote her on August 28. A week later, he beamed, “Rumor is quite rife that I have been actually appointed Lt. Gen’l.” Stuart was further heartened by word from Hood that he would not accept promotion over Stuart’s head. Indeed, Stuart credited Hood with no ambitious maneuvering, and that “the Hood imbroglio” was the work of “some of his eager friends.”

In the end, Stuart would be disappointed. On Septem-

ber 9, Lee’s headquarters issued its reorganization of the army’s cavalry, and while some officers received promotion, Stuart did not. According to Douglass Southall Freeman in Lee’s Lieutenants, Lee did not believe the

command of his cavalry carried responsibility equal to that of an infantry corps.

The two generals never crossed paths again. Within a year, Stuart met his fate at Yellow Tavern, Va. By then, Hood had joined the Army of Tennessee. –S.D.

America’s Civil War thanks the Virginia Historical Society and The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History for

permission to quote from the J.E.B. Stuart’s letters held in their collections.