During the British monarch’s six-decade reign a wave of fanatical Islamic uprisings threatened to sunder her global empire

In the years since the 2001 terrorist attacks on New York’s World Trade Center and the Pentagon in Washington, D.C., several of the Western world’s major military powers—most notably the United States—have been embroiled in a seemingly endless war against self-proclaimed Islamic militants. Many such fighters consider themselves jihadists—holy warriors against the enemies of Islam. While the United States and other “nascent” nations might be excused for believing the rise of radical Islam is a modern development, aimed at toppling the world’s current Western powers, the struggle of course dates back centuries to the rise of Islam itself. More recently, in the Victorian era, the British empire waged a similar struggle against fanatical Muslim armies.

Of the numerous enemies Queen Victoria faced during her six-decade reign, three in particular stand out: the Hindustani Fanatics, whose hostile actions in the border zone between British India and Afghanistan prompted the costly 1863–64 Ambela campaign; the Mahdists of Sudan, who in the 1880s and ’90s ruled that country with a theologically rigid and brutal fist; and the Pathans of India’s North-West Frontier, who rebelled against British rule on an unprecedented scale in the late 1890s. Behind all three uprisings were Islamic religious leaders who inflamed adherents to wage jihad against the world’s most powerful empire.

Though based in India, the Hindustani Fanatics were not Hindus but members of the fundamentalist Wahhabite Islamic sect. Many lived in the north Indian river plain, a region Turkish, Afghan and Iranian rulers had termed Hindustan, or “Land of the Hindus”—a term the British later adopted. The founder of Wahhabism was Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab, a man of limited means and education born in 1703 in Najd, a region of present-day central Saudi Arabia. Abd al-Wahhab pressed for a return to strict monotheistic Islamic worship, or tawhid, and regarded Christian believers in a triune God as sorcerers worthy of death. He ingratiated himself to powerful emirs and grew in influence. Abd al-Wahhab died in 1792, but his hard-line doctrine endured, and by the mid-19th century Wahhabism had spread to India.

In 1826 an Indian-born Wahhabite imam named Ahmad and several hundred followers entered the Yusufzai tribal region in what would become India’s North-West Frontier (in present-day Pakistan). At the time Yusufzai lands lay within the Sikh empire, and Ahmad’s aim was to stir up the tribesmen against their rulers. Though the Sikhs quickly put down the uprising, Ahmad continued to attract followers and by 1829 had the Yusufzai territory virtually under his thumb. Two years later he attacked and occupied the city of Peshawar, only to be again defeated—and this time killed—by the Sikhs. The surviving Wahhabis took refuge in Sittana and kept the rebellion on low boil under one of the emir’s lieutenants.

It was after the First Anglo-Sikh War of 1845–46 that the victorious British first clashed with the Hindustani Fanatics, when the latter supported the Hassanzai tribe during the 1852–53 Black Mountain campaign. In late 1851 the rebellious Hassanzais had hacked to death two British customs officials and occupied two regional forts, prompting the punitive expedition under Lt. Col. Frederick Mackeson. The British quickly drove the tribesmen and allied Fanatics from the forts and went on to destroy their villages and crops.

The next clash came during the Indian Rebellion (aka Sepoy Mutiny) of 1857–58 as disaffected sepoys of the Bengal Native Infantry rebelled against their British East India Co. masters. While the mutiny was being put down elsewhere in India, a British field force under Maj. Gen. Sir Sydney Cotton fought a series of actions against the Fanatics, who had incited mutineers in Peshawar. In the spring of 1858 Cotton chased the offending Fanatics across the North-West Frontier, finally driving them from their sole remaining stronghold at Sittana on May 4. After receiving assurances from local clans to refrain from allying with the Fanatics, Cotton withdrew his force.

By far the most serious conflict between the British and the Hindustani Fanatics came during the 1863 Ambela campaign. After their defeat at Sittana five years earlier the surviving Fanatics had withdrawn to the Punjab mountain outpost of Malka, where they slowly rebuilt their strength. From there they mounted continual raids against settlements in British India. Per modus operandi, the British organized a military expedition to punish the offending tribesmen.

On Oct. 18, 1863, the lieutenant governor of the Punjab dispatched the Ambela Field Force under Brig. Gen. Neville B. Chamberlain on what the British anticipated would be just another minor campaign in the North-West Frontier’s storied history. Chamberlain’s straightforward objective was to advance on Malka and destroy it—along with the Fanatics. The general chose a line of march through the Ambela Pass, expecting that tribesmen of the surrounding Buner region would not interfere with the 6,000-man British force.

But the Fanatics had duped the Bunerwals into believing the expedition’s actual purpose was to seize their lands. Thousands of tribesmen therefore rallied to help the Fanatics repel the British, as did Akhund Abdul Ghaffur, a ruling mullah in the Swat Valley who three decades earlier had sheltered Ahmad’s Wahhabite refugees. Chamberlain’s force reached the pass on October 20, oblivious to the overwhelming force allied against them.

Two days later Bunerwal fighters attacked a British reconnaissance patrol, prompting Chamberlain to fortify his positions in the pass, including two key rocky outcrops dubbed Eagle’s Nest and Crag Piquet. The main Bunerwal force, comprising some 15,000 fighters, repeatedly attacked the British positions. After they overran Crag Piquet on October 30, British Lts. George Fosbery and Henry Pitcher fought determinedly to counterattack and reclaim the point, each later receiving the Victoria Cross.

The seesaw battle for the pass continued for four weeks, Chamberlain himself falling seriously wounded on November 20. British reinforcements ultimately arrived to bolster his beleaguered troops, and in early December Maj. Gen. John Garvock took command and seized the initiative, finally breaking the tribesmen’s resistance. The Bunerwals submitted to him on December 17, and the British subsequently razed the Fanatic stronghold of Malka.

The British had suffered nearly 1,000 casualties—by far the largest loss an Anglo-Indian force had incurred on the North-West Frontier. But they had delivered a mortal blow to the Hindustani Fanatics, who were never again able to mount serious opposition.

Sudanese Mahdists conducted perhaps the best-known jihad against the British empire. The roots of that conflict lay in the rise of Muhammad Ahmad Ibn as-Sayyid Abd Allah.

Born the son of a boat builder in 1844 on the Nile River island of Labab, 10 miles south of Dongola in northern Sudan, Muhammad Ahmad became a devout Muslim as he grew into a young adulthood. In 1861 he entered studies under the Sammaniya, a particularly strict Islamic religious sect. The outspoken and charismatic young man ultimately broke with the movement’s leader to assume leadership of a competing sect, and in 1881 Muhammad Ahmad proclaimed himself the true Mahdi, or messianic redeemer of the Islamic faith.

The notion of the Mahdi is not found in the Quran but referenced in the Hadith, a narrative of the actions and words of the prophet Muhammad. Adherents of the two main Islamic denominations, Sunni and Shia, have differing views as to the concept of the Mahdi. Most Sunnis believe he has yet to appear, while Shias believe he has already been born, disappeared and will return only when ready to dispense justice and rid the world of evil. Islamic scholars continue to debate the identity, meaning and legitimacy of the Mahdi, but in 1881 the concept of a “redeemer” greatly appealed to many Sudanese Muslims.

Sudan was then under the rule of Ottoman Egypt, which had established a degree of independence from its Turkish overseers. Corruption was rampant within the Egyptian ruling elite, and many Sudanese—including Muhammad Ahmad—resented their masters. That year the self-proclaimed Mahdi initiated a revolt, and despite the Egyptians’ considerable efforts to crush the Mahdists, Muhammad Ahmad only grew stronger.

Both Britain and France had loaned large sums of money to Egypt, primarily to finance the Suez Canal, and the Ottoman Egyptians were struggling to make scheduled repayments. Wishing to protect its investments—particularly the canal, the all-important gateway to India—Britain invaded and occupied Egypt in 1882. In early 1884, when the growing Mahdist revolt threatened European civilians and Egyptian soldiers in the Sudanese capital of Khartoum, the British sent a force under Maj. Gen. Charles Gordon to evacuate them. Having fulfilled his mission, Gordon grew reluctant to surrender the British hold on Sudan. Defying his orders, he chose to defend Khartoum. Muhammad Ahmad’s army—known as the Ansar—soon put the city under siege.

Initially reluctant to commit additional troops to Sudan, the British government and Cairo authorities eventually authorized an expedition to rescue Gordon. Led by Adj. Gen. Sir Garnet Wolseley, an old friend of Gordon’s, the relief force failed to reach the Sudanese capital before the city fell to the Ansar. The Mahdists killed Gordon and sent his severed head to Muhammad Ahmad. Five months later the Mahdi himself died of typhus.

With few exceptions the British kept out of Sudanese affairs and chose to concentrate on rebuilding Egypt. While the Mahdists remained largely unchecked, Ahmad’s successor, Abd Allah ibn Muhammad—known to followers as the Khalifa—lacked his predecessor’s charisma and leadership skills and was forced to fight his way to sole leadership of Sudan.

In 1896 the British authorized a military operation against the Mahdists. Despite the ongoing public outcry to “avenge Gordon,” it was a move born out of geopolitical necessity. That spring Ethiopian forces under Menelik II had decisively defeated Italian occupiers at Adwa, securing that kingdom’s sovereignty while calling into question Rome’s control of neighboring Eritrea. When the Mahdists sought to exploit the Italians’ vulnerability by launching cross-border raids, Rome in turn asked London to alleviate pressure in the region by launching a military operation against Sudan. Driven in part by fear of French encroachment in the Nile Valley, Prime Minister Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, Lord Salisbury, agreed to send in British troops.

What followed was Brig. Herbert Kitchener’s celebrated two-phase reconquest of Sudan. His capture of the Mahdist stronghold of Dongola in 1896 fulfilled the British promise of conducting a “demonstration” to aid the Italians. Given that campaign’s success, both London and Cairo authorized Kitchener to thrust deeper into Sudan in hopes of retaking Khartoum and destroying the Mahdists.

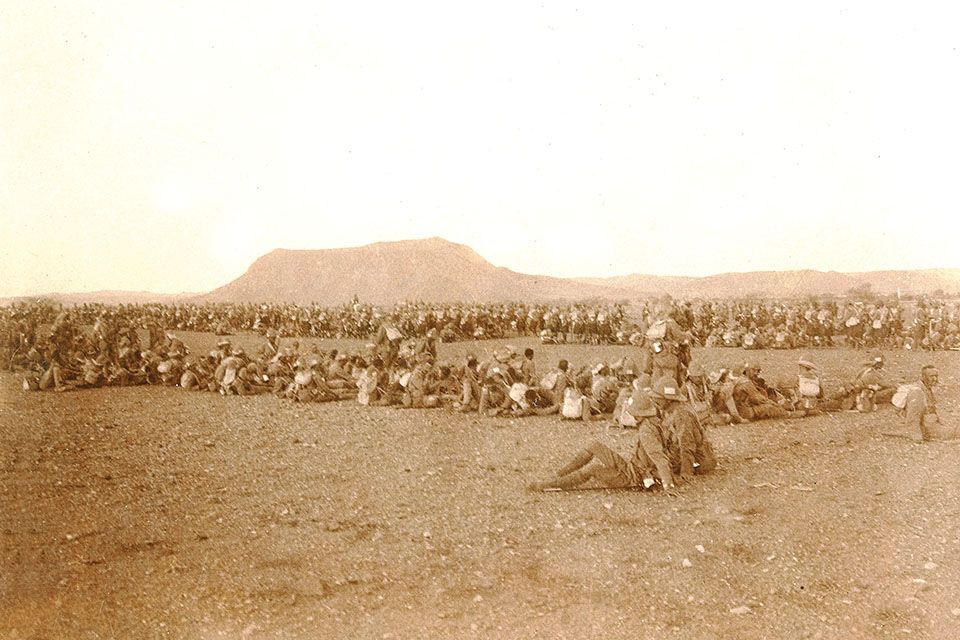

The follow-up campaigns of 1897–98 culminated in the Sept. 2, 1898, Battle of Omdurman, in which Kitchener’s 26,000-strong Anglo-Egyptian force defeated a Mahdist force more than twice its size. At the height of the fighting the 21st Lancers—among whom rode young Lt. Winston Churchill—drove back a determined Mahdist counterattack. With the Ansar defeated and Omdurman in British hands, Kitchener had effectively put an end to Mahdism, although the Khalifa himself evaded the British for more than a year before dying in battle.

Around the time Kitchener was wrapping up his reconquest of Sudan, British forces in India were confronting the last major jihad of Victoria’s reign—a series of large-scale Pathan uprisings along the North-West Frontier in 1897–98. (The British used the term “Pathan” to collectively describe the many tribes then inhabiting the frontier; today they are referred to as Pashtuns and largely reside on either side of the Afghanistan-Pakistan border.)

After annexing Punjab in 1849, the British initially attempted to keep the tribesmen north of the North-West Frontier at arm’s length, but the Pathans frequently raided into British-held territory. In response the British sent out detachments to the offending parties to exact fines or disarm them. Such expeditions were usually brief, incurred few casualties and ended in the submission of the tribe.

In 1893 British authorities and the emir of Afghanistan struck an accord known as the Durand Line agreement, formally establishing the spheres of influence each would have over the territories comprising the North-West Frontier. Neither side consulted the tribesmen, who considered such borders arbitrary and unnecessary. Following the 1895 Chitral campaign, authorities in British India also decided to retain a foothold in that far northern princely state to counter perceived Russian territorial expansion—all part of the “Great Game” for control of Central Asia. That required construction of a road to Chitral through Pathan territory and the establishment of garrisons to protect it—all of which the tribesmen saw as a threat to their independence.

Seizing on their feelings of unrest were a number of fanatical Islamic imams forever seeking jihad against the British. These included a Punjabi named Najm-ud-Din from the village of Hadda, whom the British called “Hadda Mullah”; and a Bunerwal named Saidullah Khan, whom the British dubbed the “Mad Fakir.” Each traveled from tribe to tribe, spreading unrest and consolidating resistance.

The situation came to a head on June 10, 1897, when a British political officer named Herbert Gee sought to collect a punitive fine from a string of Tochi Valley settlements known collectively as Maizar. After receiving a cordial welcome, Gee and his 200-man military escort came under ambush from a larger force of Pathan tribesmen. Gee survived the subsequent fighting withdrawal from Maizar, but the Pathans killed most of the British officers and 22 sepoys and wounded another 30 men. A punitive British expedition ended with the usual success, but a general uprising soon broke out across the frontier.

Swat Valley tribesmen under the Mad Fakir conducted a weeklong siege of the British garrisons at Malakand and Chakdara, prompting deployment of the Malakand Field Force under Brig. Gen. Sir Bindon Blood (Lt. Churchill was also a member of this force and later wrote a book about the campaign). Pathan rebels under Hadda Mullah launched a similar assault on the British garrison at Shabkadr and looted and burned the nearby Hindu village of Shankargar. With the help of two more British divisions, Gen. Blood wrapped up his punitive expedition in the Malakand District by year’s end. Meanwhile, the large and powerful Afridi and Orakzai tribes also rose in revolt, necessitating dispatch of the Tirah Field Force under Gen. Sir William Lockhart. It fought some of the most desperate battles of the uprising, including a desperate last stand in the village of Saraghari by 21 Sikh soldiers against some 10,000 Orakzais. By year’s end Lockhart, too, was able to quell the uprising in his district. The greatest threat to British authority in Central Asia since the 1857–58 Sepoy Mutiny was over within months. Queen Victoria, who had assumed the throne in 1837, capped her Diamond Jubilee year with a victory. Britain’s longest-reigning monarch to that time died on Jan. 22, 1901, at age 81.

So passed into history the Victorian-era jihads, in which bands of poorly armed radical Islamists rocked the British empire. Though largely forgotten in the West, memories are long in the regions where Wahhabis, Mahdists and members of other fanatical Muslim sects took root. Indeed, among the modern-day adherents of Wahhabism was 9/11 planner Osama bin Laden. The struggle against radical Islam continues.

British military historian Mark Simner is a regular contributor to several U.K.-based magazines. For further reading he recommends his own Pathan Rising: Jihad on the North West Frontier of India, 1897–1898, as well as The Savage Border: The Story of the North-West Frontier, by Jules Stewart, and Khartoum: The

Ultimate Imperial Adventure, by Michael Asher.