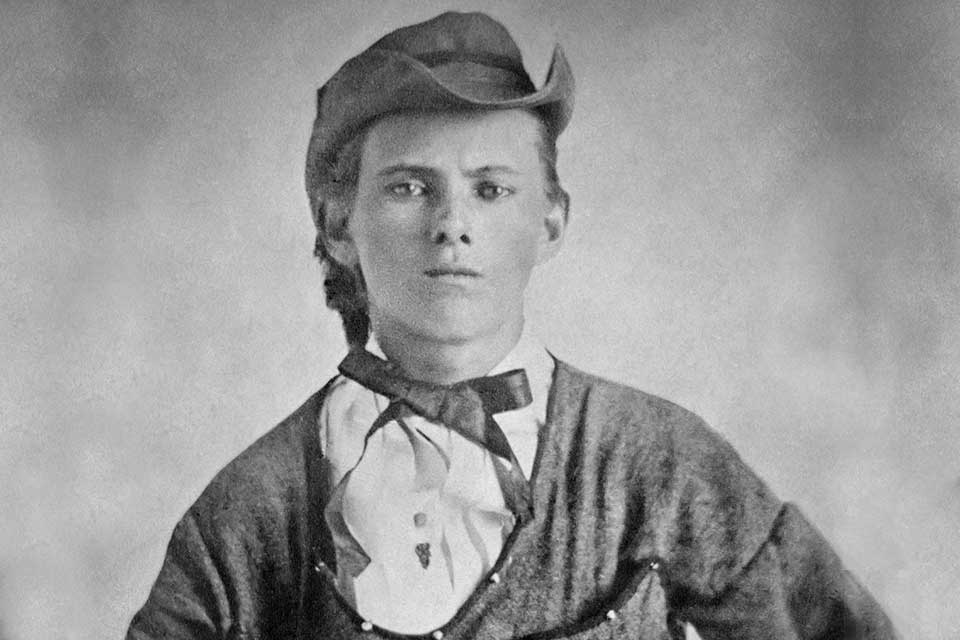

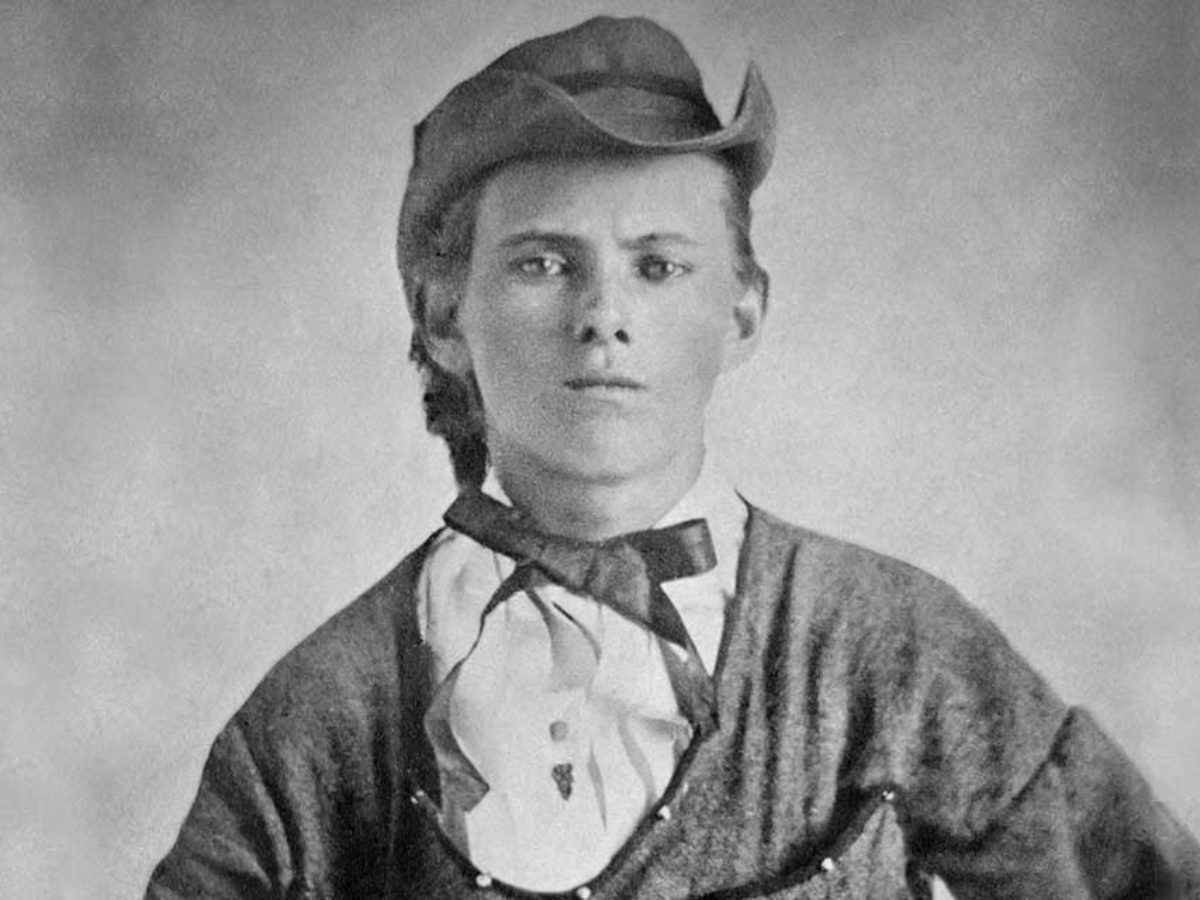

John Koblas is a prolific writer, with more than 50 nonfiction books to his credit, as well as a popular fiction series for young readers and at least 500 published short stories, articles and poems. Minnesota history fascinates him, and Jesse James and other 19th-century outlaws are a special interest. His 2006 book “Jesse James in Iowa” (North Star Press) comes on the heels of such titles as “The Jesse James Northfield Raid,” “When the Heavens Fell: The Youngers in Stillwater Prison” and “The Great Cole Younger & Frank James Wild West Show.”

Koblas has done work on documentaries for the History Channel, the Discovery Channel, PBS and others. He has taught at Bevard College in North Carolina and the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, written features for the Daytona Beach News Journal and a syndicated column for Columbia Features. Recently he talked to Wild West Magazine about his writing.

Why have you spent so much of your time writing about the James boys?

Koblas: Actually my books focusing on the James-Younger Gang make up a very small percentage of my writing output. To date, I have written 51 books on numerous subjects—both nonfiction and fiction—and fewer than 10 are about Jesse and his gang. The Jesse books, however, have all been written in the past decade, which makes it seem as if this is all I write about.

My interest initially was not so much in Jesse James but in Minnesota history. The Northfield raid, of course, was the only time the gang tried to pull off a robbery in Minnesota, so I was really looking at this from a regional perspective. As I got more and more into it, my interest shifted, or I should say expanded, to include the outlaws.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

And now you have written about what the James Gang did in Iowa prior to the attempt to rob the Northfield Bank in Minnesota?

“Jesse James in Iowa” is my eighth book on the James-Younger Gang — ninth if you count “The Return of Jesse James,” a book I wrote for young teens. I have always believed the Corydon and Adair robberies in Iowa have not received the attention they warranted, unlike those in Missouri, and, of course, the Minnesota raid. My intent was to write only about the Adair incident, but the bold swagger of the gang in pulling off the Corydon job soon fascinated me as well.

You certainly take the time to detail the events leading up to each robbery and the geographic locations.Why do you find these robberies significant?

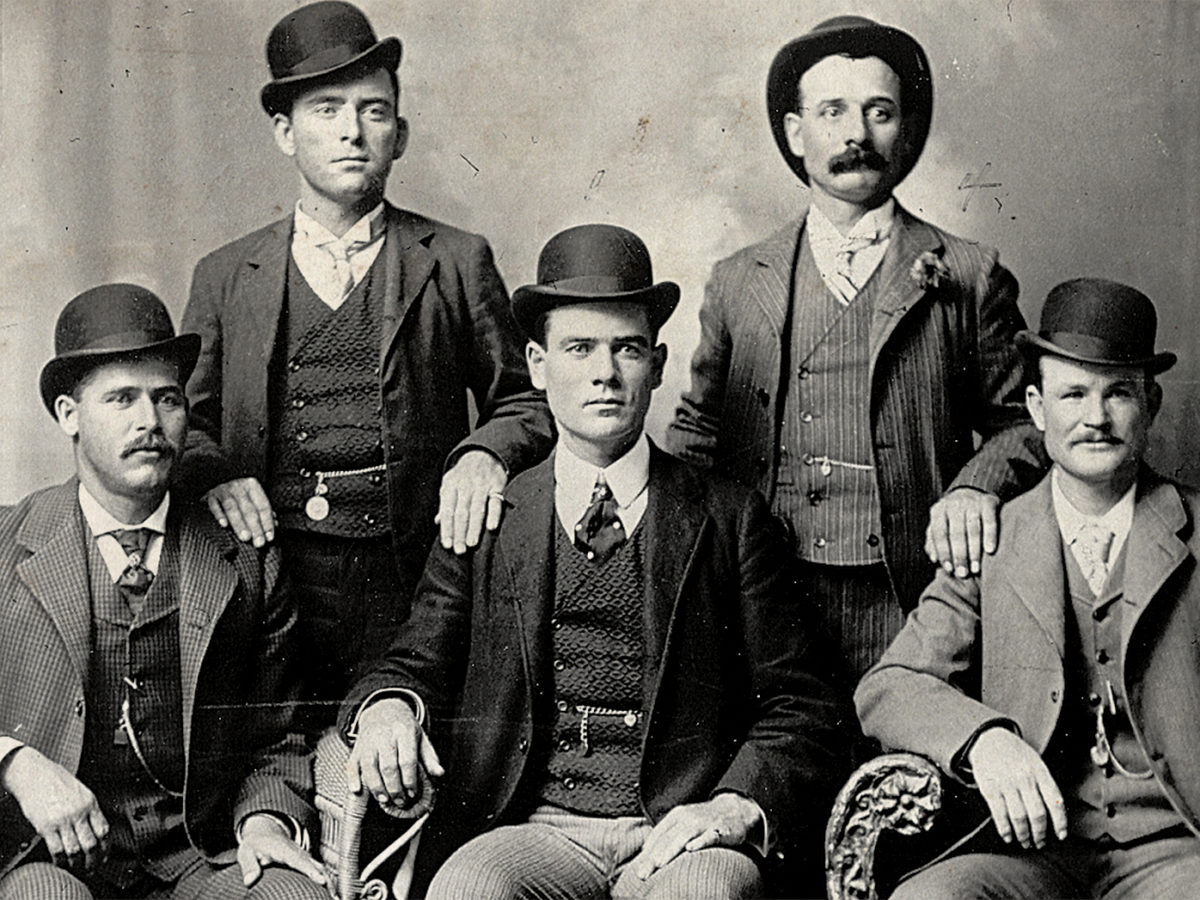

I guess it’s because I feel that “Outlaws of the Old West” needs a new definition. Granted Wyatt Earp and Billy the Kid drew attention to the American Southwest and others like the Wild Bunch operated in what we still consider the West. But so many others who are regarded as outlaws of the West — such as the James and Younger boys, the Reno brothers, Sontag brothers, Maxwell brothers, “Black Bart of Wisconsin” Reimund Holzhay and several others — committed their dastardly deeds not in the West but in the Midwest triangle (Nebraska to Minnesota to Illinois down to Missouri and Arkansas). In a sense what I am doing is retelling these stories, but in doing so, placing them in their true geographical locations. And as for details both major and minor, I attempt to give the reader a clear understanding of who the participants were and why they reacted in the ways they did.

How many bank robberies did the James Gang commit in Iowa?

The James-Younger Gang pulled off a single bank robbery in Iowa when they robbed the Ocobock Brothers Bank in Corydon on June 3, 1871. Wayne County had been remarkably free from crime. The fact that a band of robbers could come into a town in broad daylight, rob a bank and then escape was sufficient to alarm bankers across the country. Two years later [at Adair, Iowa], on July 21, 1873, the boys broke into a handcar house, purloined a spike-bar and hammer with which they pried off a fish-plate connecting two rails and extracted the spikes at a curve of railroad track near the Turkey Creek Bridge. The men quickly tied a rope on the west end of the disconnected north rail, passing the rope under the south rail to a hole they had cut in the bank in which to conceal themselves. Rock Island Line’s passenger train No. 2—made up of two Pullman sleeping cars, five coaches and an express-baggage car—jumped the track, and the engineer was killed. The outlaws robbed the train and fled into Missouri.

Recommended for you

How many robberies altogether for the boys?

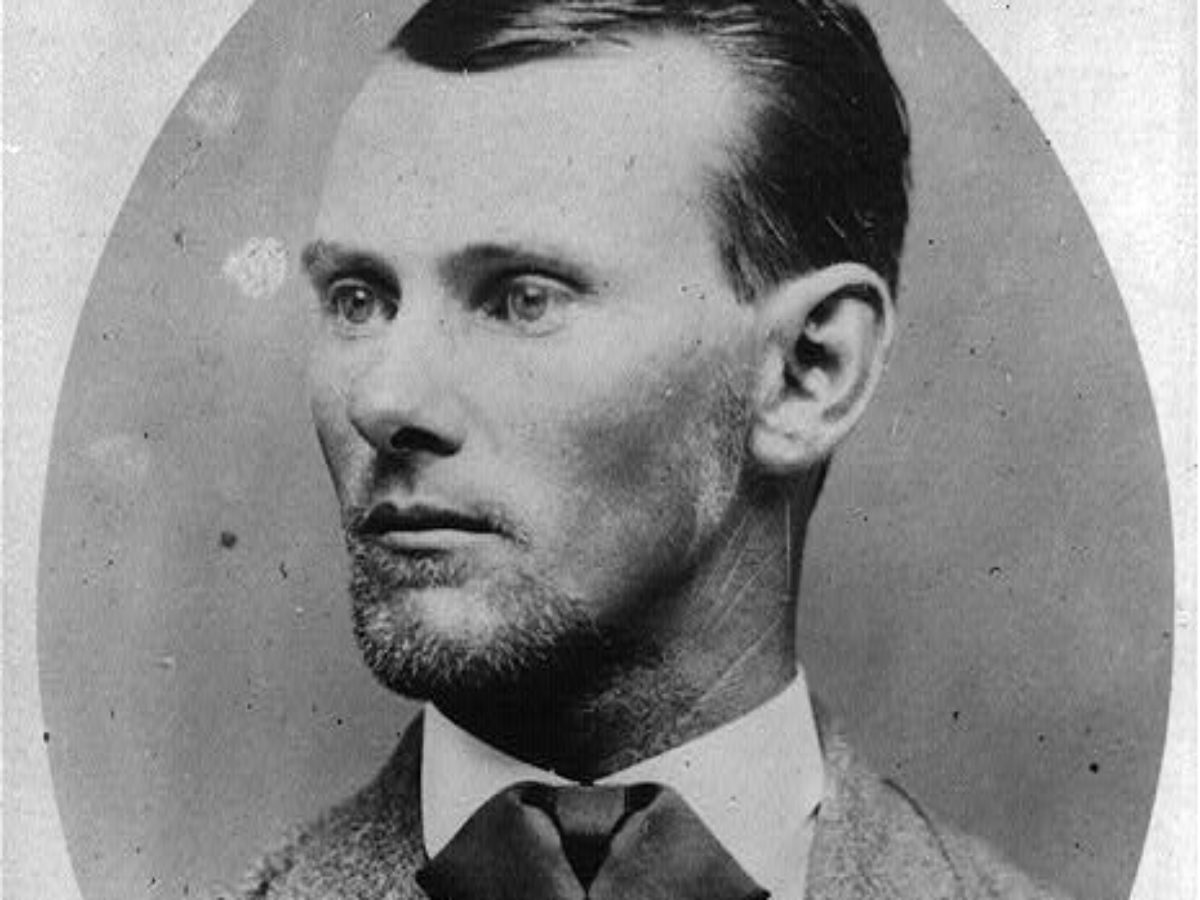

With all the copycat robberies committed by other outlaws, it is difficult to place an exact figure on their “withdrawal” activities. The Clay County Savings Bank in Liberty, Mo., was robbed by 10 to 14 men — Frank James among them. It is doubtful Jesse participated. Banks in Lexington, Mo.; Russellville, Ky.; Gallatin, Mo.; Corydon, Iowa; Columbia, Ky.; Kansas City Fair Box Office; Ste. Genevieve, Mo.; and Northfield, Minn., can pretty much be linked to the boys, as well as trains at Adair, Iowa; Gad’s Hill, Mo.; Muncie, Kan.; Otterville, Mo.; Glendale, Mo.; Winston, Mo.; Blue Cut, Mo.; and Mussell Shoals, Ala. Robberies committed at Savannah, Mo.; Richmond, Mo.; Hot Springs, Ark.; San Antonio, Texas; Corinth, Miss.; Huntington, W.Va., and others are often attributed to the gang but may have been copycats.

Didn’t the bank robberies take their toll on individuals as well as the owners?

Because the federal government did not cover losses resulting from bank robberies as it does today, merchants and farmers who had a stake in the bank were virtually wiped out.

The James Gang stole how much through the years?

A figure would be difficult to ascertain since it is not known how many robberies were, in fact, committed by the Jameses and Youngers. And in many cases where the boys were definitely involved, numbers vary considerably as to the actual amounts appropriated.

Why did Jesse and Frank make a show of denying their participation in robberies?

Self-preservation! By denying any role in illegal activities, Frank was protecting Jesse while Cole Younger was protecting his brothers Jim and Bob. And, of course, no one wants to go to prison.

What was Mattie Collins’ role with the gang and in the death of Jesse?

Mattie Collins was a woman of unsavory character who played a significant role as the flamboyant femme fatale in the events leading to Jesse James’ betrayal and assassination. Always a lady of great mystery, Mattie was the lover or wife of Dick Liddil, who was a principal member of the James Gang in later years. Mattie might have gained her bad reputation because she consorted with Liddil without the formality of marriage. Some sources refer to her as a brazen harlot who had shot and killed a suitor who had jilted her. It was she who contacted the law at Liddil’s direction to negotiate a deal to turn state’s evidence and betray Jesse. Liddil selected Mattie Collins to act as a go-between if they were to reap any benefits out of betraying Jesse because he trusted her. Mattie visited Whig Keshlear, deputy marshal of Jackson County, and asked him to contact William Wallace and cut a deal for Liddil. Wallace responded with a letter to Liddil stating that as prosecuting attorney for Jackson County, he could not make a deal to pardon him for crimes committed elsewhere, and referred him to Governor Thomas Crittenden, who had the power to do it. Mattie acted as intermediary between Liddil and the law to help him gain a pardon by betraying Jesse and others.

What is the significance of the Siam, Iowa, murder mystery that you discuss in Chapter 7 of Jesse James in Iowa?

The little-known Siam mystery is one of many events that link Mattie Collins and Dick Liddil to Frank and Jesse James. Liddil, who betrayed Jesse, also turned state’s evidence and testified against Frank James.

What projects are you now working on?

I recently completed a 1,300-page manuscript on the 1862 Dakota conflict in Minnesota. Because of its length, my publisher, North Star Press, and I have turned the project into three volumes, the first of which was released in December 2006. Titled “Let Them Eat Grass: The 1862 Sioux Uprising in Minnesota,” each book in the trilogy has its own subtitle: “Smoke,” “Ashes,” “Fire.” In addition to several other projects I am working on, I am in no way finished with Jesse James.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.