Five armed riders wearing U.S. Army overcoats stopped to have their horses shod at a village blacksmith shop on the Chalk Bluff Road in northeastern Arkansas on Tuesday, January 27, 1874. They were strangers to the area, and the bedrolls, extra clothing and other gear behind their saddles indicated they were traveling men. What’s more, each man wore several Colt Navy revolvers, three carried double-barreled shotguns, and their horses, although of superior quality, were noticeably jaded from hard riding. The blacksmith asked no questions but went straight to work. When he finished shoeing the animals, the travelers paid him and rode on.

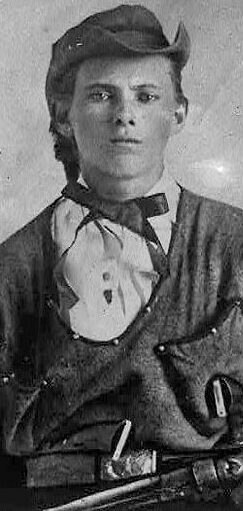

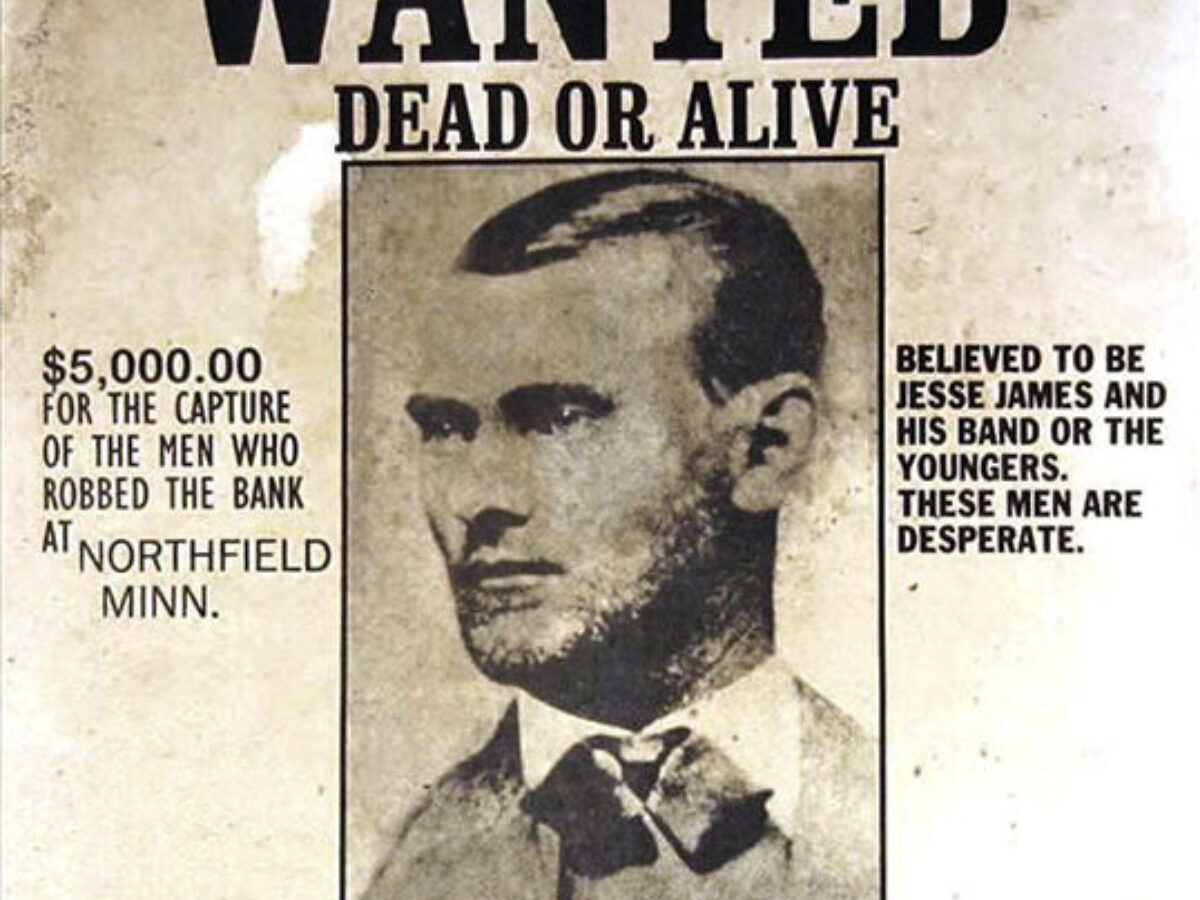

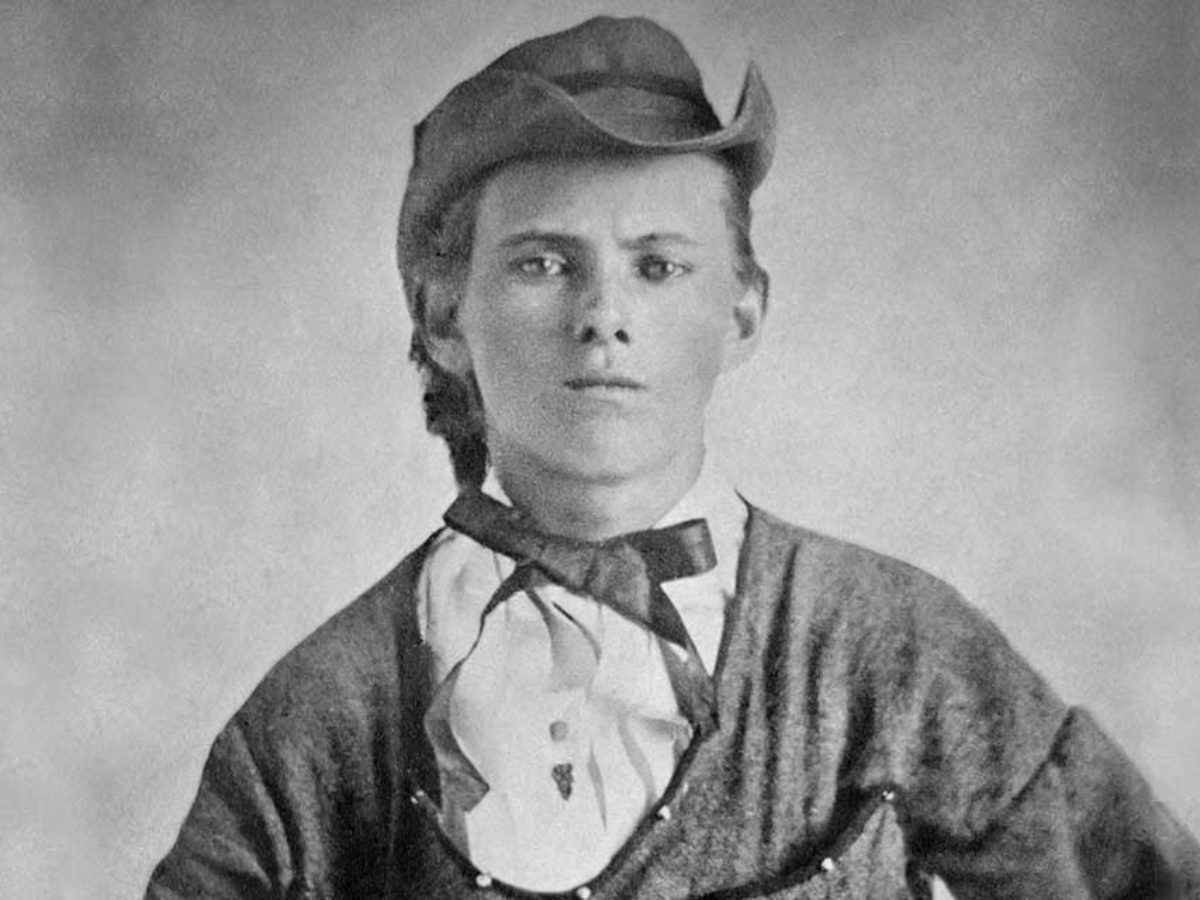

Only later would the smithy learn a shocking truth about his mysterious patrons. Newspapers reported that they were Missouri outlaws, former Confederate guerrillas, fresh from a stagecoach holdup committed January 15 near Hot Springs, Ark. Even more disturbing were their suspected identities. Calling them ‘the most daring band of robbers the country ever contained,’ the St. Louis Dispatch expressed ‘very little doubt’ that they were members of the infamous James-Younger Gang, consisting that day of Frank and Jesse James, Arthur McCoy and two of the Younger brothers.

Soon after leaving the blacksmith shop, the ‘daring band’ crossed the state line into Missouri and proceeded north along the St. Louis & Iron Mountain railroad tracks. Jesse James and his gang, it seems, had one more bit of illicit business to attend to before making the long ride back home to St. Clair and Clay counties. They were planning to rob a train — something never done before in Missouri.

ENTERING GADS HILL

Gads Hill, according to one contemporary observer, was ‘a small place, of no account.’ Situated in the piney Ozark wilderness of southeastern Missouri, 120 rail miles south of St. Louis, the tiny settlement contained only about 15 people, three crude houses, a store/post office and a small railroad platform. Passing trains generally only slackened speed there to exchange mailbags, but today would be different. On this chilly Saturday afternoon, January 31, 1874, the southbound Little Rock Express was scheduled to stop and put down a passenger — State Rep. L.M. Farris of adjoining Reynolds County. His 16-year-old son, Billy, had just arrived with team and wagon to meet him and was inside the store warming himself at the stove. Also present in the store were several men who had dropped by to chat with the storekeeper and station agent Tom Fitz. The village women were in their homes attending to chores, and their children were outside playing. The time was nearing 3 p.m., and all was well — or so everyone thought.

As the children played by the roadside, the five armed riders approached from the southeast. The men’s hats were pulled low, and their faces were hidden by white hoodlike masks with triangular-cut eyeholes. When young Ami Dean glanced up and saw these frightful-looking creatures, he ran for home, crying. ‘Don’t be afraid, little boy,’ he later recalled one of them hollering. ‘We won’t hurt you.’

The gun-toting intruders quickly robbed the storekeeper of a fine rifle and a reported $700 or $800 he kept in his coat pockets. Fortunately they missed another $450 that had slipped down in the lining of his coat. After rousting all citizens from the store and houses, the outlaws helped them build a large bonfire to ward off the cold. One of the masked men then went to work prying open the railroad switches. Their plan was to force the expected train onto the sidetrack. After this was done, everyone — men, women, children of the community and outlaws — sat back for a long wait.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Finally, at 4:45 p.m., running about 40 minutes behind schedule, the little four-car train and its 25 passengers topped the grade and approached Gads Hill. Hearing the engineer whistle for ‘down brakes,’ conductor Chauncey Alford walked to a door between cars and looked forward over the side. What he saw chilled his bones. A man was standing on the station platform waving a red flag, a railroad signal for ‘danger ahead.’ Worse, the man was masked. Alford had the safety of his passengers to worry about, so he jumped off the slow-moving train and ran toward the flag-waver to find out what was going on. As he did, he noticed the train switch onto the sidetrack. At the same moment, three other masked men crawled from under the platform and a fifth emerged on the other side of the tracks. Seizing Alford by his collar, one of them shouted, ‘Stand still, or I’ll blow the top of your damned head off!’

Young Billy Farris stood with the others at the bonfire until he saw his father appear in the doorway of one of the cars. Then, ignoring the armed guard, he ran to L.M. Farris, shouting that the train was being robbed and he should step off on the side where the villagers were. Farris did so, and he was not robbed.

As the train stopped, two of the outlaws ran forward and forced the engineer and fireman off the locomotive. Several curious passengers and trainmen stepped out on the platforms between cars, and others leaned out of windows. A masked man armed with a double-barreled shotgun shouted, ‘Take those heads back again, or you’ll lose ’em!’ Another, brandishing a revolver in each hand, ran along the opposite side of the train, warning that the conductor and engineer would be shot if anyone attempted to interfere.

The other three outlaws climbed aboard the combination mail-baggage-express car. They rifled the contents of the express safe and registered-mail packages; then two of them stepped off. The one remaining asked express agent Bill Wilson for his receipt book. Apparently he wanted to bring the records up to date. Opening the book and turning to a blank page, the thief mischievously wrote, ‘Robbed at Gads Hill.’

INTENDED VICTIMS

The robbers forced Wilson to join his fellow crewmen on the platform. Then, some of the former guerrillas moved to the passenger cars. At first they announced they would only rob the’sons of bitches’ who wore high silk hats (or ‘plug hats,’ as they called them), but they soon added they would also rob ‘Goddamned Yankees,’ regardless of their hat styles. Capitalists — men who came by their money easily — were also on their hit list. ‘Workingmen’ and ladies would be spared. The bandits began examining the palms of male passengers. Men with soft hands were robbed; men with calloused hands were not. A minister, who was passed by when he told them his profession, asked if the outlaws might stop a moment so he could pray for them. ‘We hain’t time,’ the leader responded, but then added, ‘You pray for us tonight…that we may all get to the good country.’

The passengers’ fears were eased somewhat by the light-hearted behavior of their abductors. As the masked men walked the aisle, they made jokes, patted the heads of children and bowed politely to the ladies. One of them exchanged his battered slouch hat for the much finer hat of a well-dressed gentleman. When a rather intoxicated Irishman offered his flask and said, ‘Won’t you have a drink, boys?’ the leader answered with a chuckle, ‘No, sir, I’m afraid you might have it spiked.’ But it wasn’t all fun and games. The robbers seemed to think that a famous Chicago detective was aboard and repeatedly asked, ‘Where’s Mr. Pinkerton?’ For 2 1/2 years, Allan Pinkerton and his Pinkerton National Detective Agency had been ardent pursuers of the James-Younger Gang, and the outlaws were apparently intent on doing him in. Several male passengers suspected of being the sleuth were threatened. One was even taken to a private compartment and strip-searched for a Pinkerton’secret mark.’ All proved their identities and lived to travel another day.

Just before stepping off the coach, the robber who had requested prayer from the preacher turned and spouted a few lines of William Shakespeare. Although it was never reported what lines he quoted, they may have been from King Henry IV. In that play, the bard used Gad’s Hill, England, after which the Missouri village (without the apostrophe) was named, as a setting for a highway robbery pulled off by Sir John Falstaff and friends. It has been suggested that perhaps Frank James’ love for that play, or Shakespeare in general, was a determining factor in the selection of Gads Hill, Mo., as the robbery site.

The wealthiest passengers were in the Pullman car. Among those to hand over his money was a despised, soft-handed, plug-hatted Minnesotan who had the misfortune of being named Lincoln. ‘Any Goddamned son of a bitch [with] that name ought to be shot!’ one of them growled. John F. Lincoln was, by one account, robbed of about $200, and when his hat (accidentally?) fell to the floor, the bandit gave it a swift kick. Lincoln later voiced a strong opinion that this particular robber was Cole Younger.

Also aboard this coach was James H. Morley, chief engineer of the Cairo & Fulton Railroad, a St. Louis & Iron Mountain subsidiary. When Morley stood up and protested the robbery of the company for which he worked, a revolver was placed under his nose. ‘Sit down, shut your head, and mind your business,’ he was told. Had the gunman known that Morley indeed was minding his business, it wouldn’t have mattered. The railroad executive still would have been fleeced of $15. Morley’s wife was not robbed, but when they came to another woman in the car, the rules suddenly changed. A Mrs. Scott was traveling from Pittsburgh to Hot Springs, Ark., with her young son and carrying the hefty sum of $400.10. When she presented the money, the noble bandits apparently forgot their promise to not rob ladies and took all but the dime.

CUB REPORTER

At last, satisfied they had gotten all the desired monies and valuables from the train, one of the thieves walked back to John Lincoln and handed him a piece of paper. On it was scribbled a detailed account of the train holdup, complete with a headline. The outlaw said he had written it for the newspapers to make sure that this time they reported the facts correctly.

It read:

THE MOST DARING

ROBBERY ON RECORDThe south bound train on the Iron Mountain railroad was boarded here this evening by five heavily armed men and robbed of ______ dollars. The robbers arrived at the station a few minutes before the arrival of the train and arrested the agent and put him under a guard and then threw the train on the switch.

The robbers were all large men, none of them under six feet tall. They were all masked and started in a southerly direction after they had robbed the express. They were all mounted on fine blooded horses. There’s a hell of an excitement in this part of the country.

Lincoln turned the article over to conductor Alford, and, although not entirely accurate, it would later appear in several newspapers as part of their coverage of the crime.

The amount stolen from the train was never reported with certainty, but Alford, who should have known, stated that the bandits made off with $2,500, four registered money packages (one of which contained $2,000), a gold watch, five pistols, one ring and a diamond stick pin. Newspaper estimates ranged from $2,000 to $22,000.

Having completed the heist, the outlaws paused to shake hands with the engineer and thank him for his hospitality. Alford and another crewman went to close the switches, and while this was being done, the robbers galloped away. Besides money and valuables taken from the train, they also stole three fine saddle horses from the village.

BACK ON TRACK

Alford was happy to finally have his train rolling again. At Piedmont, seven miles south, he reported the robbery by telegraph to the Iron Mountain headquarters in St. Louis. From there the news spread like wildfire. Indeed a ‘hell of an excitement’ had been orchestrated in Missouri, and at least a stir would be felt across the nation.

On Sunday morning, a posse of 25 armed horsemen set out in pursuit of the villains. Others joined in along the way. Although a slight snowstorm had occurred during the night, the possemen had little trouble following the trail. The retreating gang, it was discovered, had forded Black River six miles northwest of Gads Hill and then taken the Lesterville road north to the three forks. On Middle Fork the posse recovered a spent horse. It was one of those stolen at Gads Hill and reportedly belonged to a member of the posse.

As was the custom among traveling horsemen of the day, Jesse James and his friends often stopped for food and lodging at farmhouses. Stories of some of those visits were reported in contemporary newspapers; others have been handed down. In all instances, according to news accounts, ‘they behaved very genteelly’ and paid all their bills ‘lavishly.’

Recommended for you

The train robbers proceeded along Black River until they came to its West Fork. Turning west, they followed that stream into northwestern Reynolds County. By then they were badly in need of fresh horses. The Salem Success reported, ‘In one instance they paid $130 for a horse and shot one they were riding, substituting the fresh one.’ The newspaper may have been referring to an incident that is said to have happened one night near the confluence of West Fork and Tom’s Creek. They supposedly stopped there at the farmhouse of James and Elizabeth Sutterfield, and asked to buy a horse, as one of theirs was worn out. Should he refuse to sell, they told James Sutterfield, they would take the horse anyway. Sutterfield had little choice, and the deal was made. After saddling the fresh mount, the buyer drew a revolver and shot the jaded horse in the head. As it fell kicking in the barnyard, the strangers rode away. The next morning Sutterfield went out to bury the animal and was shocked to find it still alive. With proper care the wounded horse eventually recovered and lived on the farm for many years as a local celebrity.

Jesse James and his gang continued across the state and Tuesday night stayed at the home of a widow named Cook, who lived on Current River about one-half mile above the mouth of Gladden Creek. Two of them appeared to be brothers, Mrs. Cook later said, ‘being very much alike in form and face.’ They left at 4 o’clock the next morning and, according to the widow, went two abreast about 100 yards apart, the odd man riding last and leading a spare horse. Some two miles upstream, near a gristmill at Welch Spring, they forded the river and proceeded across Texas County to Big Piney River. Along the way they continued their practice of paying farmers for food and shelter. Horses, though, were usually ‘borrowed.’

Their next reported stop was at the Mason farm, where they arrived Wednesday evening. Dexter Mason, soon to be elected state representative, was in Jefferson City, but his wife agreed to feed the travelers and put them up for the night. Sometime after they left the next morning, three farmers rode up in search of thieves who had stolen their horses. Mrs. Mason, already suspicious of her houseguests, was now virtually certain she had entertained the robbers of Gads Hill.

POSSE PURSUIT

Also still in pursuit was the main posse, although it was rapidly losing enthusiasm and members. When the men left the trail Thursday evening and rode up to Licking for a much-needed night’s rest, there were only 11 remaining — and they, too, soon admitted defeat and headed home.

By now reported sightings of the long riders were becoming fewer. On the morning of February 12, they were spotted about three miles northeast of Phillipsburg crossing the railroad tracks at Brush Creek. Then, at shortly past midnight on February 18, a Bolivar couple was awakened by the sound of passing horses and from their bedroom window observed five men of the outlaws’ descriptions riding down the street. A newspaper supposed they were bound for nearby St. Clair County, where the Younger brothers often stayed with friends.

It is indeed likely that the Youngers did stop in St. Clair County, while Frank and Jesse (and perhaps the fifth man) continued on to their mother’s farm near Kearney in Clay County. When they arrived there during the first week of March, Allan Pinkerton already had agents en route. Among them were Joseph W. Whicher, assigned to locate the Jameses, and Louis J. Lull and John H. Boyle, assigned to hunt the Youngers.

On the evening of March 10, Detective Whicher arrived at Kearney by train. Posing as a farm laborer in search of work, he naively believed he could outwit and single-handedly capture the James brothers on their home turf. That night he set out on foot for the James farm. The next morning his lifeless body, shot in the head, neck and shoulder, was found along a roadside in neighboring Jackson County. One week later, Lull, Boyle and a hired guide, part-time Deputy Sheriff Edwin B. Daniels, were accosted by Jim and John Younger on a road near Roscoe in St. Clair County and a deadly gunfight ensued. Cole Younger later claimed his brothers had stopped the detectives only to explain that they were innocent of the Gads Hill affair, and had Lull not overreacted, no one would have been harmed. As it was, John Younger, Daniels and Lull all died from their wounds.

Some months passed and Allan Pinkerton, still bitter over the deaths of his agents, sent a squad of detectives by special train to Clay County with orders to capture the elusive James brothers and burn down their mother’s home. At shortly past midnight on January 26, 1875, the Pinkerton men and a neighboring farmer, Daniel Askew, attempted to do just that. During the raid, a fireball, supposedly intended only to light up the interior, was tossed through a kitchen window. When someone inside panicked and swept it into the fireplace, the device exploded, killing the James boys’ 8-year-old half-brother and blowing off their mother’s right forearm. Efforts to burn the house failed, and the detectives fled. On the night of April 12, Askew was gunned down in his backyard. Revenge may also have been the motive in July 1881 when conductor William Westfall was murdered by Jesse and his gang during a train robbery near Winston, Mo. Westfall may have been in charge of the train that carried the Pinkertons to Clay County the night of the fatal bombing.

WHODUNNIT?

Who were the robbers of Gads Hill? There is little doubt that the James brothers were among the culprits. Later, Jesse’s widow even admitted so. Jesse’s share of the loot, which she said was one-fifth of $2,000, financed their wedding and honeymoon trip to Sherman, Texas. And what outlaw other than Frank James would have been so original as to quote Shakespeare while robbing a train?

As for the Youngers, Cole insisted that he and his brother Bob were visiting a friend, William Dickerson, in Carroll Parish, La., at the time of the robbery. Dickerson and 10 of his friends verified the claim. Jim and John Younger, on the other hand, had no alibi, and it might be speculated that they were the two robbers described by widow Cook as looking like brothers. Another reason for suspecting Jim and John is that they showed up in St. Clair County at about the time the retreating outlaws passed through the area.

The fifth man stood over 6 feet tall and was 40 or more years old, a description that matched known gang member Arthur McCoy. While he and the other suspects were being hunted, a St. Louis newspaper printed an anonymous letter that claimed McCoy had recently died in Texas. His ‘death’ had supposedly occurred just prior to the raids at Hot Springs and Gads Hill, making him innocent of those crimes. The mysterious letter may have been written by one of McCoy’s friends, or even by McCoy himself, in an effort to get the law off his back. At any rate, his demise at that time was never proved and, in the opinion of this writer, he remains a chief suspect.

Gads Hill, once described as ‘a small place, of no account,’ later became, for a few years during the lumber boom, a thriving community of some 600 people. It had at one time three steam sawmills, a water-powered gristmill, a hotel, a blacksmith shop and even a railroad depot. Eventually, though, as the pine forest was decimated and the timber industry slacked off, people began moving away.

The face of Gads Hill has changed many times over the years. Houses and stores have come and gone; the railroad station is no longer there; and an old oak tree, where legend claims Jesse tied his horse, died years ago. As of this writing, the former settlement consists only of one house, a bar and grill and two ‘city limit’ signs. A historical marker near the robbery site reads: ‘Gads Hill Train Robbery. Jesse James and Four Members of His Band Carried Out the First Missouri Train Robbery Here, January 31, 1874.’

The Gads Hill train raid was not as lucrative as some of the other James-Younger robberies. For example, the July 1876 train holdup near Otterville, Mo., netted the bandits more than $15,000. However, of all the crimes associated with these men, Gads Hill undoubtedly did the most to create the myth of Jesse James as an American Robin Hood. Reports of the outlaws stealing from the rich passengers aboard the train and tales of their giving to the poor widows and farmers as they escaped across the Ozarks are legendary. The chain of tragic events spawned by the crime, though, present a darker side to Jesse and his gang that even romanticists can’t ignore. These accounts of both good and evil, all byproducts of Gads Hill, aroused national interest in the outlaws when they were reported and remain to this day integral parts of the Jesse James story

This article was written by Ronald H. Beights and originally appeared in the June 2005 issue of Wild West.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.