Although Irish scholar Damian Shiels trained in the archaeological study of conflict, he expanded his focus a decade ago to the Irish connection to the Civil War. While preparing for an exhibition of the military history of Ireland at the National Museum of Ireland in 2007, he discovered the U.S. government pension files, brimming with details about Irish-born veterans and their families. Shiels is the author of The Forgotten Irish: Irish Emigrant Experiences in America and since 2010 has blogged at irishamericancivilwar.com.

CWT: Explain your sources.

DS: I do most of my research in Cork, where pension files of widows and dependents from the National Archives that have been digitized are available on Fold3. Over the last 5-6 years I’ve been systematically going through every unit from each state and looking for Irish people and going into the files for correspondence. I also looked at the 1883 List of Pensioners on the Roll, ordered by Congress. It includes all the countries outside the United States.

CWT: What treasures have you found?

DS: Those pension files have soldiers’ letters, but the real value of the pension files is you can follow people across 30, 40, 50 years. It tends to be the women that you’re following, and they give extraordinary detail about their lives. A lot of work has been done recently on the Civil War in a global context, but the 19th century women’s pension files represent the greatest source of information on Irish people anywhere in the world, including Ireland. We have nothing here approaching that. Historians in Ireland haven’t really looked at the American Civil War.

CWT: Why not?

DS: We don’t have any censuses left, they were all destroyed. The earliest is 1901. In the U.S. pension files, emigrants can say exactly where they are from, what their experience was, and how they lived in Ireland. It’s absolutely vital information for 19th century Irish history. The files are of the Civil War but they are not only about the Civil War. It’s their social importance—what it tells about their lives in the 19th century.

CWT: Who created the files? Were people literate?

DS: More common than not, the soldiers themselves are not literate. You regularly come across this in the files, so not only are the soldiers ostensibly writing the letters not literate but the people they’re sending the letters to aren’t literate. Someone in the company writes a letter for the soldier, say to the Five Points in New York City, and when it arrived, someone who was literate would come and read it to the intended recipient.

CWT: The postal system worked surprisingly well.

DS: The most common thing you find in nearly all the letters is soldiers at the front complaining that people haven’t written to them from home. And they’re always asking for stamps and paper so they can correspond with them.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Irish historians haven’t really looked at the Civil War[/quote]

CWT: Give me an example of the close communication you’ve found.

DS: A Union sailor off the Confederate coast was able to write a letter back to his father in Sligo on Ireland’s west coast, and ask if his neighbor had joined the Confederacy, as he heard he might be facing him across the Harbor. It’s incredible that you could communicate from the blockade to the west coast of Ireland and get a response back so speedily. Soldiers write from places like Petersburg and their letters are printed in Irish newspapers relatively quickly. There is really this continual link. You see it in the files when people are trying to prove a marriage in Ireland. They can usually write back to someone from their home area that they might have left 30 or 40 years previously, so it shows that they’re maintaining links. This flies in the face of the idea that these people leave and there’s no connection to home.

CWT: How many Irish fought?

DS: Normally you hear 150,000 Irish-born served, but that’s too low, based on 19th century analysis that excludes huge sections like the Navy and the Regular Army—which were at least 20 percent Irish-born in the war. The estimates I worked up suggest about 180,000 Irish-born in the war. That’s not a true reflection either, because you have the American-born children. I come across a lot of British-born and Canadian-born children of Irish people, who often see themselves not only as Americans but also as ethnically Irish. The files also show that very, very few Irish come back once they go to the United States, even when they have the opportunity to do so.

CWT: How do you learn about what happened after the war?

DS: Some of the best information you get out of the pension files is when the bureau suspects that fraud has been committed, particularly by women. So when they suspect fraud, they carry out these exceptionally extensive interviews which are just a gold mine for social information—for example, women who remarry and then claim their pension. There was a big moral element to all of this, of course. The pension bureau had these special examiners who would go around and check out all this. And there was undoubtedly quite a lot of fraud. There was an industry surrounding the pension system, with agents who were handling all these cases for these people. It was a massive industry well into the 20th century.

CWT: What is a big misconception people have about the emigrants?

CWT: What is a big misconception people have about the emigrants?

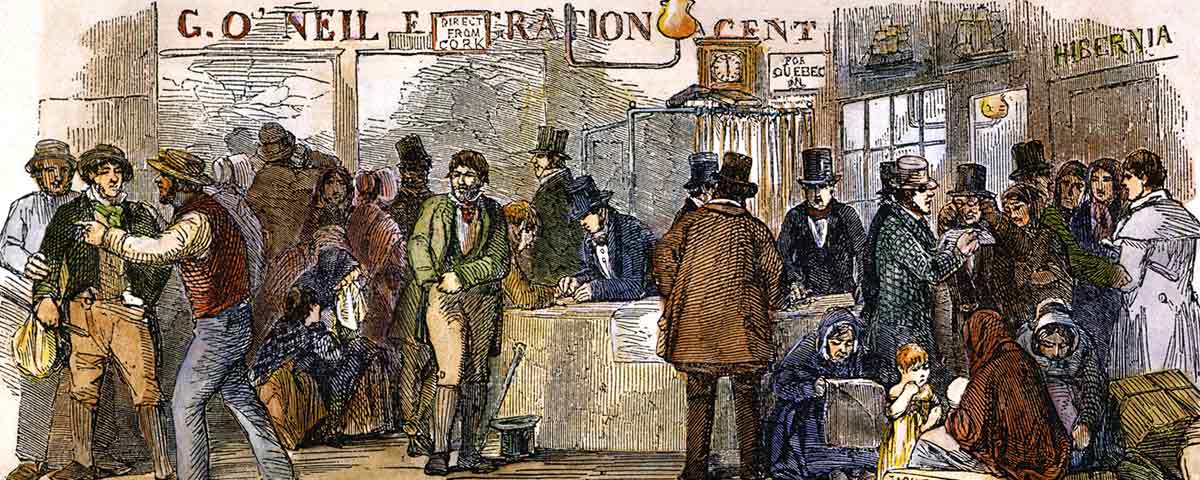

DS: The movie Gangs of New York shows the Irish as clueless, hopping off the boat and being enlisted in the Army and not knowing what’s going on. If you read the correspondence, though, the military was saying they couldn’t enlist them straight off the boat because the emigrants would write letters home and tell people not to come. Often Irish soldiers tell their own family to not join the military because it’s such a hard life. What you definitely get is Irish men living in Ireland during the war who see emigration as an opportunity to get into America, to get citizenship and financial reward. The story isn’t so much guys coming off the boat and being duped into enlisting. The more common story is guys going from Ireland to America to enlist in the Union military because they see it as an opportunity for them and their families.

CWT: So people in Ireland had a good grasp on the war?

DS: People in Ireland are fully aware of what is going on. During the war there was even a theater show in Ireland that depicted the American war: The Polopticomorama toured Britain and Ireland portraying great scenes, like the Monitor and Virginia fight. It’s a very global war. People are very interested and a flood of correspondence is going back and forth across the Atlantic. The Irish press are writing after Fort Sumter that there are more Irish-born soldiers in the garrison than American soldiers. The first men to die at Fort Sumter—because of an accidental explosion—were Irish. In 1861 an Irish paper writes that before the war is over “many a [Irish] fireside…will be filled with mourning as each American mail arrives.”

CWT: Is that true?

DS: The only war in modern Irish history that compares with the American Civil War in terms of the numbers who served is World War I. For all the Irish counties on the western seaboard and the southwest, and those worse affected by the potato famine, the Civil War has a huge impact. More people from those locations fought in the war than in any other war, ever. ✯

Interview conducted by Senior Editor Sarah Richardson