Do Union icons John Reynolds and John Sedgwick deserve their reputations?

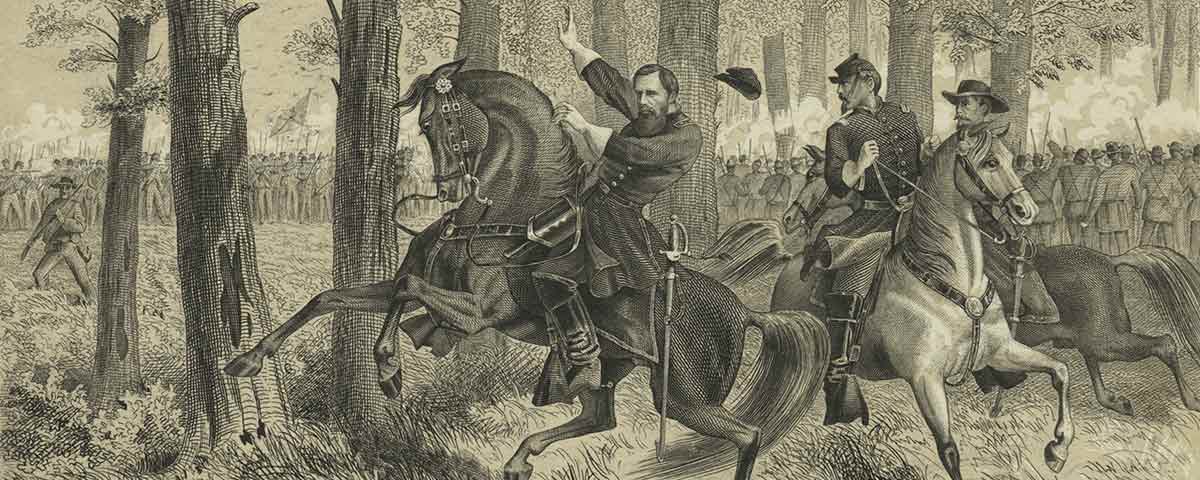

[dropcap]M[/dropcap]ajor Generals John Fulton Reynolds and John Sedgwick died in striking circumstances that undoubtedly burnished their reputations as successful Union corps commanders. On July 1, 1863, at Gettysburg, Reynolds accompanied the leading units of his 1st Corps into action. Positioned behind the Iron Brigade’s 2nd Wisconsin near the eastern fringe of McPherson’s Woods, he urged his troops to stop the approaching Confederates. “Forward men,” he shouted, “forward for God’s sake, and drive those fellows out of the woods!” Turning to look back toward Seminary Ridge, he went limp in the saddle after a Minié ball entered the back of his neck. He was dead before hitting the ground. Sedgwick’s story on the second day of the Battle of Spotsylvania could be conjured from a novelist’s imagination. Steadying a portion of his 6th Corps line opposite Laurel Hill on the morning of May 9, 1864, he noticed men dodging as Confederate musket rounds struck nearby. “I am ashamed of you,” he told them: “They can’t hit an elephant at this distance.” He repeated those words, with a good-natured laugh, after a sergeant dropped to the ground for safety. A moment later, an unmistakable thud told observers that Sedgwick had been hit, incurring a mortal wound just below his left eye.

William Swinton, who covered the Army of the Potomac for The New York Times, anticipated the tenor of many subsequent evaluations of the two generals. Reynolds’ death, wrote Swinton in Campaigns of the Army of the Potomac (1866), was “a grievous loss to the Army of the Potomac, one of whose most distinguished and best-loved officers he was; one whom, by the steady growth of the highest military qualities, the general voice of the whole army had marked out for the largest fame.” As for Sedgwick, the “loss of this lion-hearted soldier caused the profoundest grief among his comrades, and throughout the army, which felt it could better have afforded to sacrifice the best division.” Edward J. Nichols, whose Toward Gettysburg: A Biography of General John F. Reynolds (1961) remains the most detailed biography, quotes Winfield Scott Hancock, the Comte de Paris, Joseph Hooker, and others proclaiming Reynolds the best soldier in the army. In General John Sedgwick: The Story of a Union Corp Commander (1982), Richard Elliott Winslow III pronounces his subject “a steadfast soldier who contributed much to ultimate Union victory” in the course of playing a “crucial role during the Civil War.”

Did Reynolds and Sedgwick merit such praise? As corps chiefs, the answer must be no. At Fredericksburg, Reynolds’ initial battle as head of the 1st Corps, the commander’s penchant for overseeing details relating to his artillery rendered him ineffectual in directing the activities of key subordinates such as George G. Meade. One careful student of the battle concludes that Reynolds’ dallying among the guns “made him completely ineffective when Meade sought critical reinforcements.” At Chancellorsville, Reynolds and his corps saw almost no action, suffering fewer than 300 of the army’s more than 17,000 casualties. His actions at Gettysburg on July 1 were solid but scarcely sufficient to warrant extravagant praise.

Sedgwick’s terrible wound in the West Woods at Antietam, where his division was butchered, kept him out of the Fredericksburg Campaign. Promoted to command of the 6th Corps, he played an important role at Chancellorsville, where his corps absorbed the heaviest casualties in the army. Sedgwick’s actions on May 1-5 certainly lacked aggressiveness and have inspired a good deal of criticism. Edward Porter Alexander, the most astute of all Confederates who wrote about the war in the Eastern Theater, pulled no punches: “I have always felt surprise that the enemy retained Sedgwick as a corps commander…, for he seems to me to have wasted great opportunities, & come about as near to doing nothing with 30,000 men as it was easily possible to do.” At Gettysburg, Sedgwick’s corps, the army’s largest, played only a minor part in the fighting and lost just 212 men killed or wounded.

Sedgwick put in a mixed performance during the Battle of the Wilderness, earning praise from U.S. Grant for his bravery but receiving harsh critiques from others for allowing John B. Gordon’s successful flank attack on May 6 against the 6th Corps. “This stampede,” wrote Theodore Lyman of Meade’s staff regarding Gordon’s routing of two Union brigades, “was the most disgraceful thing that happened to the celebrated 6th corps during my experience of it.” Lyman also thought some of Sedgwick’s other actions “amounted to nothing.”

Both Reynolds and Sedgwick unquestionably inspired a good deal of admiration. A pair of officers, one from each general’s staff, offer useful testimony on this point. Stephen Minot Weld met the ambulance carrying Reynolds on July 1, which triggered a surge of emotion. “He was the best general we had in our army,” wrote Weld in his diary: “Brave, kind-hearted, modest, somewhat rough and wanting polish, he was a type of the true soldier. I cannot realize that he is dead.” Sedgwick’s nickname—“Uncle John”—revealed the degree to which his soldiers thought of him as a leader who looked after their welfare. Thomas W. Hyde referred to Sedgwick as “our friend, our idol.” Hyde described the feeling when news of the general’s death settled in: “Gradually it dawned upon us that the great leader, the cherished friend, he that had been more than father to us all, would no more lead the Greek Cross of the 6th corps….”

Such heartfelt tributes should not obscure that neither Reynolds nor Sedgwick crafted a sterling record as a corps commander. Both fit comfortably within the culture George B. McClellan created in the Army of the Potomac. That culture prized caution, seldom sought a killing blow to the enemy, and accepted, almost preferred, inaction to any movement that might yield negative results. Yet, their dramatic deaths lifted Reynolds and Sedgwick to a special position in the pantheon of Union generals. As Edward J. Nichols admitted in his biography of Reynolds, “A hero’s death sits well with posterity.” ✯