No part of Robert E. Lee’s record as a Confederate general has occasioned more criticism than his decision to launch Pickett’s Charge

[dropcap]F[/dropcap]ollowing the carnage of Maj. Gen. George Pickett’s failed frontal assault against the Union center at Gettysburg on July 3, 1863, General Robert E. Lee rode among survivors of Pickett’s Division as they returned to the sheltering slopes of Seminary Ridge. Luckily for future students of the battle, Sir Arthur James Lyon Fremantle, the British observer and diarist temporarily attached to James Longstreet’s headquarters, was on the scene to record Lee “engaged in rallying and in encouraging the broken troops.” When Brig. Gen. Cadmus M. Wilcox approached the commanding general, “almost crying” in Fremantle’s judgment, “Lee immediately shook hands with him and said, cheerfully, ‘Never mind, General, all this has been MY fault—it is I that have lost this fight, and you must help me out of it in the best way you can.’” This example of Lee’s willingness to take responsibility for his own decisions—it was his fault—provides powerful evidence of his style of generalship’s gruesome cost.

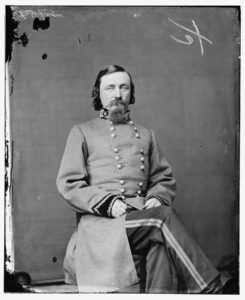

As friendly a witness as Edward Porter Alexander, who considered Lee a supremely gifted officer, judged his old chief’s tactical offensive on the third day at Gettysburg harshly: “[C]ertainly in the place & dispositions for the assault on the 3rd day, I think, it will undoubtedly be held that he unnecessarily took the most desperate chances & the bloodiest road.” Confederate cavalry general Wade Hampton, while recovering from wounds incurred at Gettysburg, wrote that the Pennsylvania Campaign was a “complete failure” during which Lee resorted to unimaginative offensive tactics. “The position of the Yankees there,” the South Carolinian insisted, “was the strongest I ever saw & it was in vain to attack it.”

Why did Lee select such a risky and potentially costly course? The prudent decision, as Porter Alexander pointed out, would have been to shift to the defensive following the Confederate tactical victory on July 1. But Lee overlooked the Federals’ superior ground, waived off objections from James Longstreet, and, frustrated by what he considered substandard performances from J.E.B. Stuart, Richard S. Ewell, and A.P. Hill, decided to risk a great deal on the afternoon of July 3. In the end, a breathtaking confidence in his infantry likely proved the decisive factor in dictating Lee’s course on July 3.

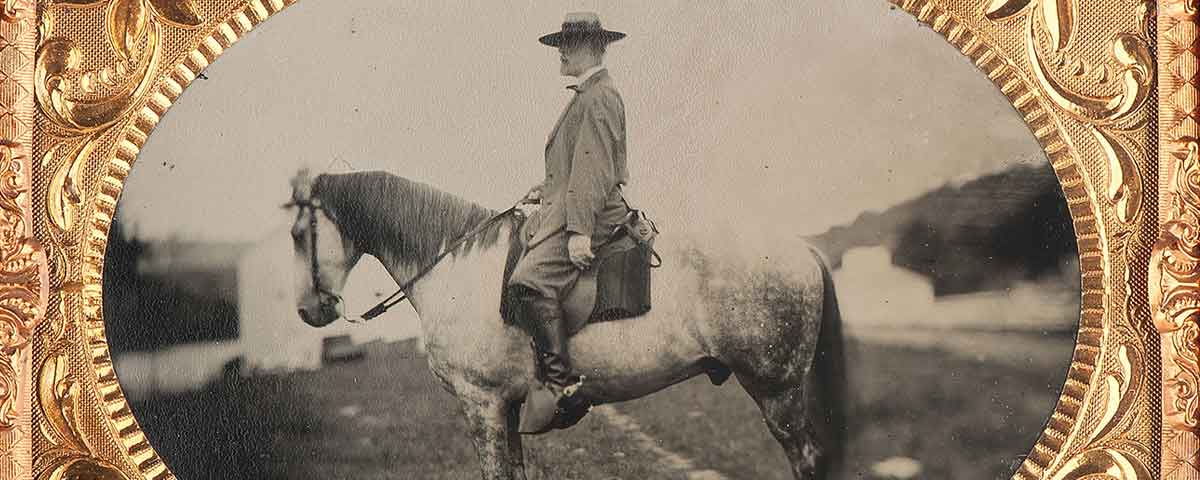

A memorable episode at Chancellorsville two months earlier helps explain Lee’s behavior at Gettysburg. Heavy fighting forced a Federal withdrawal on the morning of May 3, and Lee rode northward from Hazel Grove to the Plank Road, then turned east toward Chancellorsville crossroads. A mile’s ride carried him to a scene that no artist could improve. Confederate artillery south of the Plank Road sent deadly missiles into the ranks of retreating Federals. Smoke from woods set afire by musketry and shells drifted skyward. Just north of the Plank Road, in a clearing that had been the center of Hooker’s line, stood the Chancellor House, itself ablaze with flames licking at its sides. Lee guided Traveller through thousands of Confederate infantrymen, general and mount dominating a remarkable tableau of victory. Emotions flowed freely as the soldiers, nearly 9,000 of whose comrades had fallen in the morning’s fighting, shouted their devotion to Lee, who acknowledged their cheers by removing his hat.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Why did Lee select such a risky and potentially costly course?[/quote]

Seldom has the bond between a successful commander and his troops achieved more dramatic display. Colonel Charles Marshall of Lee’s staff captured the moment: “The fierce soldiers with their faces blackened with the smoke of battle, the wounded crawling with feeble limbs from the fury of the devouring flames, all seemed possessed with a common impulse. One long, unbroken cheer, in which the feeble cry of those who lay helpless on the earth blended with the strong voices of those who still fought, rose high above the roar of battle, and hailed the presence of the victorious chief.” Lee basked in “the full realization of all that soldiers dream of—triumph.” Chancellorsville marked the apogee of Lee’s career as a general and cemented the reciprocal trust between him and his men that helped make the Army of Northern Virginia a formidable military instrument.

That trust impressed many observers as the Confederates entered Pennsylvania in June. Ample testimony about soaring confidence in the Army of Northern Virginia lends credence to the idea that Lee believed his infantry could do anything he asked. Fremantle addressed morale in his diary. Over supper on the evening of July 1, Longstreet discussed the reasons attacks might fail; however, added Fremantle, in the ranks “the universal feeling in the army was one of profound contempt for an enemy whom they have beaten so constantly, and under so many disadvantages.” The men’s attitude, together with Lee’s great faith in them, implied a degree of scorn for the Federals noted by Fremantle’s fellow foreign observer, Captain Justus Scheibert of the Prussian army: “Excessive disdain for the enemy…caused the simplest plan of a direct attack upon the position at Gettysburg to prevail and deprived the army of victory.”

Two of Lee’s statements at the time suggest the centrality of his unbridled confidence in the army’s rank-and-file. He wrote his wife on July 26 that the army had “accomplished all that could reasonably be expected. It ought not to have been expected to perform impossibilities,” he admitted in a sentence that could be taken as self-criticism, “or to have fulfilled the anticipations of the thoughtless and unreasonable.” Five days later, Lee wrote in the same vein to Jefferson Davis: “No blame can be attached to the army for its failure to accomplish what was projected by me….I am alone to blame, in perhaps expecting too much of its prowess & valour.”

On July 3, Lee concluded that his infantry could overcome the recalcitrance of his lieutenants, difficulties of terrain, and everything else to achieve great results. Fourteen years after the battle, former division commander Henry Heth succinctly summed up what had happened in Pennsylvania: “The fact is, General Lee believed the Army of Northern Virginia, as it then existed, could accomplish anything.” ✯