Major Robert Anderson became a Union hero for losing the fight for Fort Sumter

[divider_flat]One in every four Civil War soldiers, more than 673,000 men, surrendered at some point during the conflict.

[divider_flat]To put such numbers in context, the number of soldiers who surrendered is approximately equal to the number of soldiers killed. If death shaped the Civil War, so did surrender.

In no other American war did surrender happen so frequently. Americans have repudiated surrender in recent history, labeling it un-American. Against this background, the Civil War presents a startling contrast. Americans—Northerners and Southerners alike—frequently surrendered, usually without stigma. Although one could surrender honorably, dishonor and humiliation always loomed in the periphery and could be avoided only by carefully evaluating whom one surrendered to and whom one allowed to surrender and under what conditions.

Major Robert Anderson’s surrender of Fort Sumter in April 1861 presents a case study of an honorable surrender during the Civil War. Praised for his valor, propriety, and commitment to duty, Anderson served as a model for how to behave in combat and in surrender.

[divider_flat]

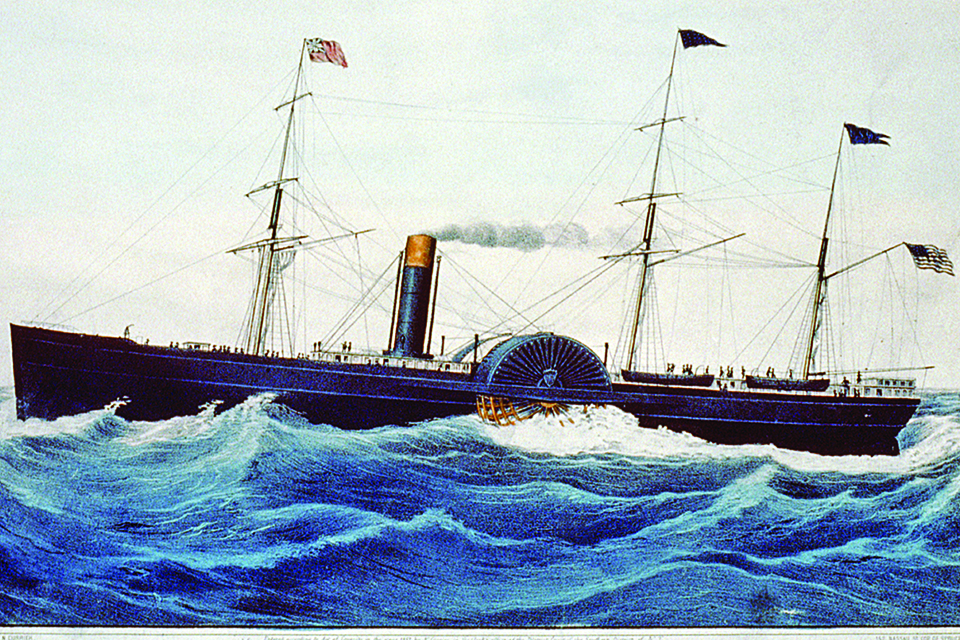

After a 36-hour bombardment that began April 12, Anderson surrendered Sumter on April 14. The major and his men were then transferred to the civilian steamer Baltic, headed to New York City. If any of the Union garrison anticipated the celebratory reception that awaited them, they showed no indication when they boarded Baltic at sunrise on April 15, 1861. Ferried to the vessel through a crowded mass of ships that filled Charleston Harbor, Captain Abner Doubleday, the fort’s second in command, noted that “the bay was alive with floating craft of every description, filled with people from all parts of the South, in their holiday attire.”

During the four-day journey to New York, Anderson, Doubleday, and their men undoubtedly reflected on the events of the previous days. Would they be blamed for not holding onto the fort longer? Anderson appeared to be physically and mentally overwhelmed by the ordeal. Dr. Samuel Wylie Crawford, the fort’s surgeon, noted that the major’s “physical as well as mental condition” made him unable to file a report on the surrender. Crawford requested that Gustavus Fox, Baltic’s captain, complete the task.

When they arrived at New York Harbor on April 19, Doubleday recalled that “all the passing steamers saluted us with their steam-whistles and bells, and cheer after cheer went up from the ferry-boats and vessels in the harbor.” A caravan of well-wishers escorted them into the harbor. The flag that had been lowered during the surrender at Sumter now flew from Baltic’s mizzenmast, “almost in rags.” The New York Tribune described Anderson as a “short, slim, bronzed-faced, and apparently feeble gentleman, whose very appearance give the lie to any doubt of his courage or patriotism. He was too exhausted and too much overcome by his emotions to speak.”

To avoid the crowds swarming Battery Park, eager to see Anderson and his men, Baltic anchored in the narrow waterway separating Manhattan and Governors Island. According to Doubleday, “Several distinguished citizens at once came on board, and Major Anderson was immediately carried off to dine.” Whatever expectations Anderson had about his reception in New York, he did not imagine that he would become the toast of the town.

The entire Fort Sumter garrison became celebrities. Doubleday noted, “Our captivity had deeply touched the hearts of the people, and every day the number of visitors almost amounted to an ovation. The principal city papers, the Tribune, Times, Herald, and Evening Post, gave us a hearty welcome. For a long time the enthusiasm in New York remained undiminished. It was impossible for us to venture into the main streets without being ridden on the shoulders of men, and torn to pieces by hand-shaking.”

The New York City that Anderson, Doubleday, and company arrived in had been transformed over the previous week. The news of Anderson’s surrender had reached the city on April 14, galvanizing a metropolis that had in recent months been a hotbed of anti-Lincoln sentiment. The New York Herald correctly predicted that “the gallant Major [Anderson] will no doubt receive a magnificent reception on his arrival to the city.” Even before his arrival, a photography store on Broadway advertised carte-de-visite “portraits of Major Anderson” for 25 cents. On April 15, diarist George Templeton Strong noted a “change in public feeling marked, and a thing to thank God for. We begin to look like a United North.” The city’s newspapers, he observed, had almost instantaneously changed their outlook; having denounced Lincoln vociferously since his inauguration, they now supported his call for troops. The lone exception to this, according to Strong, was the New York Courier & Enquirer, which “devotes its leading article to a ferocious assault on Major Anderson as a traitor…and declares that he has been in collusion with the Charleston people all the time. This is wrong and bad. It is premature, at least.”

The Courier & Enquirer’s condemnation of Anderson is worth noting, if only for its singularity and the responses it generated from its competitors. “Sumpter [sic] has fallen—surrendered, we fear, by a traitor,” the newspaper claimed, “and that traitor [is] Major Robert Anderson. This is harsh language; but it is the language of truth demanded by what appears to be the greatest act of treason ever perpetrated in this or any other country.” Rather than surrender, the newspaper argued, Anderson should have fought until “his walls [were] breached and three-fourths of his command slaughtered,” rather than “ignominiously surrender[ing] his post, and virtually proclaim[ing] himself a traitor to his country, and false to his honor, and his God.” The newspaper called for Anderson to be court-martialed for treason, his surrender a “great national disgrace.”

The other New York newspapers lambasted the Courier & Enquirer for its treatment of Anderson. In response, the Herald argued that: “Major Anderson has proved himself a brave and faithful officer. Mr. Lincoln seems to be satisfied with his conduct, and the President is, perhaps, better qualified to form a correct judgment in this case than even our Wall street contemporary….That Major Anderson is a humane man, and wished, as far as possible, to avoid the shedding of the blood of our Southern brethren, is probable; but we cannot believe that he has undergone in the service of the United States all his labors and privations since December last, and all the hardships and dangers of a bombardment of thirty hours, merely to prove himself a traitor. Let him and his officers and men be heard before he is condemned.”

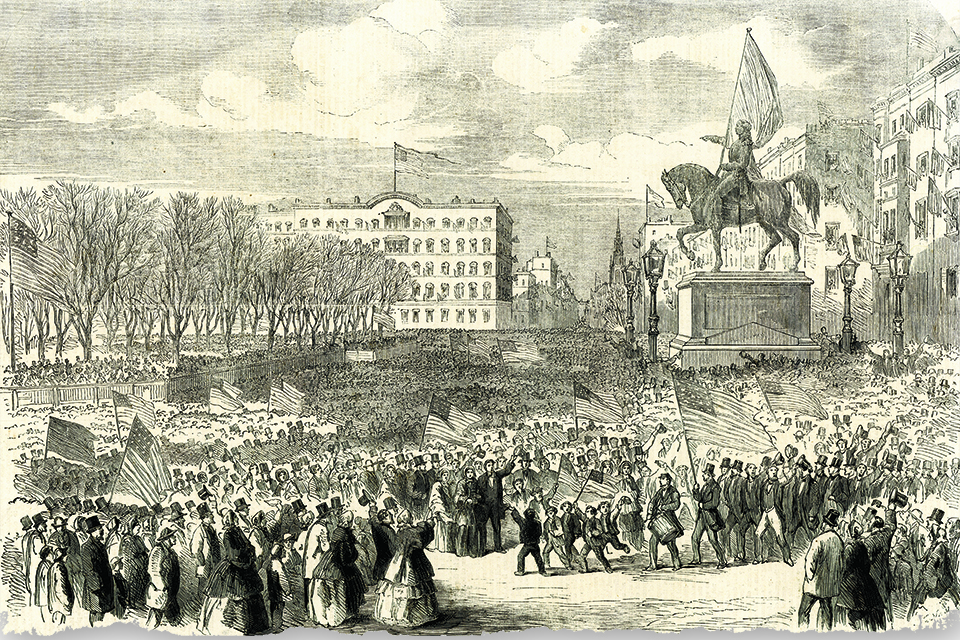

On April 17, two days before Baltic arrived, prominent New Yorkers—Democrats and Republicans alike—met at the Chamber of Commerce to organize a “monster meeting” on April 20 to honor the heroes of Fort Sumter. They decided to hold the rally in Union Square, a locale whose symbolic name was not lost on the organizers. On the morning of the Union Square rally, The New York Times observed, “This will doubtless be the largest public meeting ever held in this City, or indeed on this continent. For once the people of New-York are entirely united, and in promoting the objects for which this meeting is held, they will speak with one voice.”

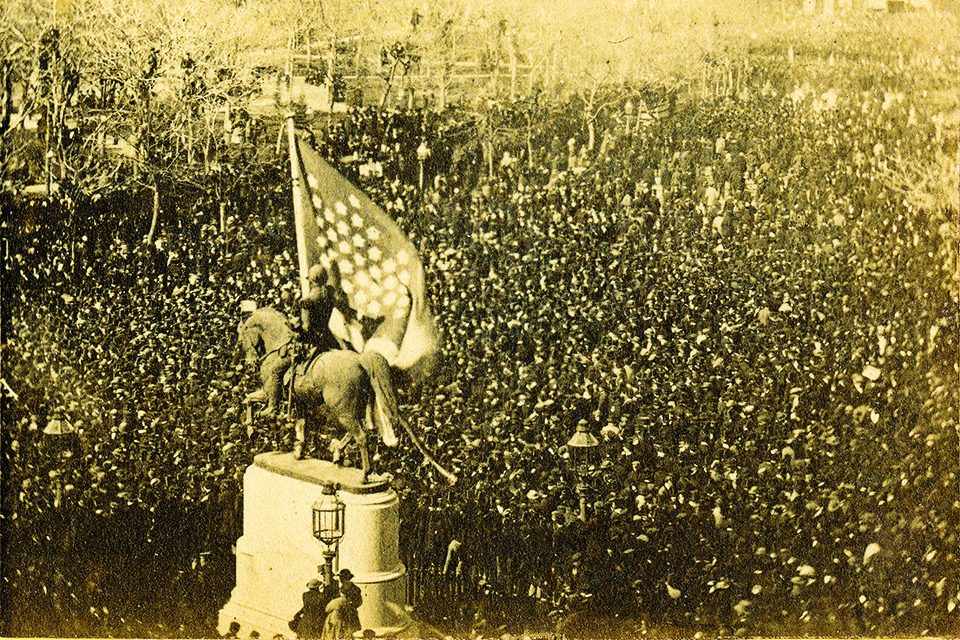

The Union Square rally would have been appropriate for a victorious general. More than 100,000 New Yorkers (The New York Times reported the crowd as “the entire population of the city”) flooded the park and the surrounding streets. The Times noted that “Broadway from Fourteenth-street almost to the Battery was a surging mass of human beings all the afternoon. The stores were closed, and everywhere, on house-tops and mastheads, and on men’s hats and next to their hearts, and even in ladies bonnets were the Stars and Stripes….Union-square was a red, white and blue wonder. Countless little flags were hung from windows or waved by ladies and children who looked forth from them.”

When Robert Anderson appeared, it was “the signal for an outburst of applause seldom, if ever, equaled. The mass of human beings seemed to recognize at once the object of attention, and it was with the greatest difficulty that the Police made way for him through the enthusiastic crowd.” As Anderson made his way to the podium, the enormous crowd swelled and roared, as “the eager populace pressed closer and closer to view the hero of the first battle in the pending war.” Unused to such attention and in poor health, Anderson appeared “nervous and agitated as he never was in the face of the enemy.” To thunderous applause, he “acknowledged the homage” with a meager wave. In the hours that followed, Anderson was praised by a series of orators as a “gallant commander,” “the Hero of Fort Sumter,” who had survived “the smoke and flame.” Over the next few weeks, Anderson was mobbed by well-wishers wherever he went. It is difficult to ascertain what the major thought about the public laudation he received in the weeks following his surrender. In poor health and physically exhausted after the siege and bombardment of Fort Sumter, Anderson remained almost entirely silent during the celebrations that greeted him in New York and in the weeks afterward.

Anderson’s decision to submit at Fort Sumter became the prototype of the honorable surrender during the war. The New York Herald identified several elements that made Anderson’s surrender heroic. First, he fought valiantly until he concluded that both continuing to fight and retreating were untenable, such that “there can be no doubt that Major Anderson did all that man could do.” With the fort on fire, “the brave soldiers in Sumter behaved as heroes.”

Second, Anderson negotiated the terms of the surrender so as not to disgrace either himself or his soldiers. He did not surrender his sword or his flag, taking both of them with him when he abandoned the fort for New York. Third, he maintained a dignified and cool demeanor throughout the battle, never succumbing to fear or passion, ever the professional soldier. Anderson’s public standing improved dramatically after the surrender. On May 1, 1861, President Lincoln wrote to Anderson that he wished to express the “approbation and gratitude I considered due you and your command from this Government,” and he asked Anderson to visit him in Washington so that he could “personally testify my appreciation of your services and fidelity.”

Anderson was promoted to the rank of brigadier general and commissioned to raise regiments in Kentucky and in western Virginia. His name and image became a common feature on patriotic envelopes, including one labeling him as the “Hero of Sumpter” [sic] and another bearing his likeness next to a depiction of the fortress flying an oversized American flag.

While those men who fought in the Civil War accepted that one could honorably surrender, subsequent generations grew increasingly un-

comfortable with surrender, repudiating it as un-American and weak. This aversion to commemorating surrender first manifested itself in a celebration marking the fourth anniversary of the fall of Fort Sumter. On the morning of Friday, April 14, 1865, more than 5,000 people assembled on Charleston’s docks awaiting ferries to take them to Fort Sumter. Two months earlier, Confederate flags had flown proudly over the city. Major General William T. Sherman’s approach had prompted General P.G.T. Beauregard, who had presided over Sumter’s bombardment and had accepted Anderson’s surrender, to evacuate the city on February 15. Three days after Beauregard’s departure, Charleston’s mayor surrendered the city unceremoniously to one of Sherman’s subordinates. Robert Anderson, now promoted to general for his heroism during Sumter’s shelling, had returned to hoist the flag he had lowered during the fort’s surrender.

General Anderson had traveled aboard the steamship Arago to Charleston from New York with other dignitaries handpicked by Lincoln to participate in the ceremony. Their number included the Rev. Henry Ward Beecher, who would give the keynote address; Liberator editor William Lloyd Garrison; and British abolitionist George Thompson, who shared a stateroom with Garrison during the voyage. Each of their lives, a New York Times reporter wryly noted, would not have been worth “the price of the rope which would have served to hang him, if he had simply ‘put in an appearance’” in Charleston a few months earlier. Joining them on board were approximately 60 others, including politicians, judges, military officials (including several of the soldiers who had surrendered with Anderson at Sumter), and reporters from the major New York and Chicago newspapers. While some of the others on board saw the planned ceremony as a symbolic end to the war—the eventual defeat of the Confederacy a fait accompli—for Beecher, Garrison, and Thompson, the return of the Union flag to Fort Sumter was the final nail in slavery’s coffin.

En route to Charleston, Arago stopped briefly at Fort Monroe, located at the southern tip of the Virginia Peninsula, where the waters of the James River join the Chesapeake Bay before flowing into the Atlantic. There the distinguished passengers met briefly with Secretary of War Edwin Stanton.

Cruising into Charleston Harbor, Arago passed Fort Sumter, which one passenger noted resembled a “Coliseum of ruins.” After four years of war, the island fort had become “battered, shapeless, overthrown…[a] monument to the broken rebellion.” After arriving in Charleston, the dignitaries were escorted to their hotel by a large contingent of newly freed African Americans, creating a procession a mile long.

Touring Charleston the next day, Arago’s passengers witnessed a city transformed. Not only were its buildings in ruins and weeds poking up through the cracked pavement, but the tenor of the city, once the birthplace of the Confederacy, had changed. The city swarmed with black and white Union soldiers enjoying a respite from four years of fighting, Northern merchants eager to reestablish trade networks severed by the war, newly freed blacks testing the limits of their freedom, and white Southern civilians, mostly women, who ventured out of their homes only when necessary, horrified at much of what they saw outside their doors. Some of the men who had left the city when Beauregard evacuated had recently returned, and some of these had taken the oath of allegiance, pledging their loyalty to the United States.

Over the next two days, other steamships brought visitors eager to observe the return of the Union flag to Fort Sumter. Among the last to arrive was Oceanus, which like Arago had voyaged from New York. Many of its 200 passengers were congregants at Henry Ward Beecher’s Brooklyn church, having spent $150 for the privilege of hearing him preside over the flag raising. When they saw Fort Sumter, the passengers began to sing the doxology in celebration. Sailors on gunboats nearby heard their chorus and joined in, taking “up the strain and manning the yards pour[ed] forth a thundering cheer.”

Oceanus bore more than Beecher’s excited parishioners; it also carried news that transformed the meaning of the next day’s flag-raising ceremony. Calling to the nearby sailors, the passengers on board yelled, “General Lee has surrendered!” The news of Lee’s surrender spread quickly throughout Charleston. The New York Times reported, “The reception of the news of LEE’s surrender…occasioned the liveliest demonstration. At the theatre, where the glorious victory was announced, the audience was wild with enthusiasm. Dense crowds filled the spacious parlors of the Charleston Hotel and gave vent to the widest latitude of jubilancy over the great event.” Politicians who had come to Charleston aboard Arago gave speeches honoring “General Grant, the old flag and President Lincoln,” which were “cheered lustily.”

After the previous night’s celebrations, many of those attending the flag-raising ceremony at Fort Sumter awoke bleary-eyed and fatigued. The New York Times noted that the “revelry and congratulations were kept up until a late hour, the joy extending into many households which had received information of the glorious news.” Starting an hour before sunrise, naval vessels “dressed in a profusion of bunting” ferried participants from the city’s docks to Fort Sumter, with the last trip bearing Anderson, Beecher, and Garrison arriving just after noon. Although the exterior of the fort had survived, its interior had become “a mass of debris composed of concrete, brick and sand in which was imbedded tons of iron missels.” An elevated speaker’s podium had been erected in the center of the parade ground, festooned with myrtle and streamers. Soldiers composed the majority of those in attendance, including black soldiers from the 54th Massachusetts, some of whom had fought at Fort Wagner. Also in attendance were the son of Denmark Vesey, executed in 1822 for organizing a slave revolt, and Robert Smalls, a former slave who stole a Confederate warship, CSS Planter, in 1862, and would later represent South Carolina in Congress.

When it came time for Anderson to raise the flag, the usually taciturn military officer shed a few tears, as did many in the audience. At the sight of the torn and battered flag, “the amphitheater saluted it with five thousand voices, and the battlements replied with two hundred guns.” One observer claimed that “it was the most exciting moment of my life when that flag went up.” When the cheering subsided, Anderson found his voice enough to say that he “was here to fulfill the cherished wish of my heart through four long, long years of bloody war, to restore to its proper place this dear flag.”

The task of finding meaning in the flag’s return fell to Beecher in what would be the afternoon’s longest oration. Speaking for more than two hours, Beecher needed to stop midway, telling the band to play a song to allow those “to get up that are sitting down, and you to sit down that have been standing; and I will sit down too, and rest a moment.” Nowhere in his speech did Beecher mention surrender, either Robert Anderson’s four years to the day earlier or Robert E. Lee’s, which many in the audience had spent the previous night celebrating. Beecher briefly alluded at the beginning of his speech to the bravery of Anderson “and a small heroic band” who “did gallant and just battle for the honor and defense of the nation’s banner.” That the battle ended in Anderson surrendering Fort Sumter went unsaid.

The absence of even one mention of the word “surrender” in the many thousands of words uttered that afternoon suggests that the speakers felt there was something unmanly or un-American about surrender. At a dinner address that evening, Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt also avoided the word. The difficulty that Beecher and others had in coming to terms with the idea of surrender is surprising, given how ubiquitous surrenders were during the conflict. Despite the ubiquity of surrender during the Civil War, in the 150 or so years since its conclusion, generations of Americans have struggled, like Beecher, to articulate what those surrenders meant.

_____

Admired in the South

Praise for Major Anderson was not restricted to the North. The Charleston Courier praised “the gallant Anderson.” The Richmond Daily Examiner observed that “the straightforward circumstances in which its garrison was placed, reflects the highest honor and credit on the gallant Major in command and the noble band of heroes that so faithfully served under him….The force at the disposal of Major Anderson was totally inadequate to the protracted and proper defense of the work….Taking all the facts together, it does not appear possible that a more gallant defense could have been made. The anxiety of the officers and the men must also be borne in mind.” The praise Anderson received from both Northerners and Southerners alike suggests that, in early 1861, Americans broadly shared a conception of honorable surrender. –D.S.

David Silkenat is a senior lecturer at the University of Edinburgh, Scotland. This article is adapted from his most recent book, Raising the White Flag: How Surrender Defined the American Civil War. Copyright © 2019 by David Silkenat. Used by permission of The University of North Carolina Press. www.uncpress.unc.edu