“The French like to maintain that the outbreak of war is always marked by a poor vintage, and victory by a gloriously celebratory one. Thus 1945 was a great vintage, 1939 mediocre, 1918 good, 1914 dismal,” writes Julian Barnes. It was as if the ground itself knew of the invasion and then, six long years later, of victory.

Soldiers drink. It’s been an enduring love affair for well over 9,000 years. Hominids learned to walk. Our Homo erectus descendants discovered fire. Man discovered alcohol. So it goes.

Alcohol and war have always been intrinsically tied, with a recent study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention revealing that “service members consume alcohol on more days of the year than any other profession.”

But during World War II the French Resistance used the Germans’ penchant to reach for a bottle before battle to gain valuable intelligence. By late 1940, the Resistance caught on that the Germans would demand large quantities of alcohol in the lead up to major campaigns.

The shipment directives themselves could be telling. Prior to the Nazi campaign in North Africa in February of 1941, the Germans ordered that French wine and champagne be specially corked and packaged for extreme heat. This information was passed on to British intelligence just prior to the invasion.

Unlike field marshal Hermann Göring or propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, Adolf Hitler was not a big drinker. However, he sought to drain French wine and champagne reserves to not only lubricate his troops, but to wreak havoc on the nation’s export of wine, and damage the psyche of the nation.

To implement this, the Nazis appointed weinführers in various regions around France. In the Champagne province, Otto Klaebisch – a French-born German – was put in charge.

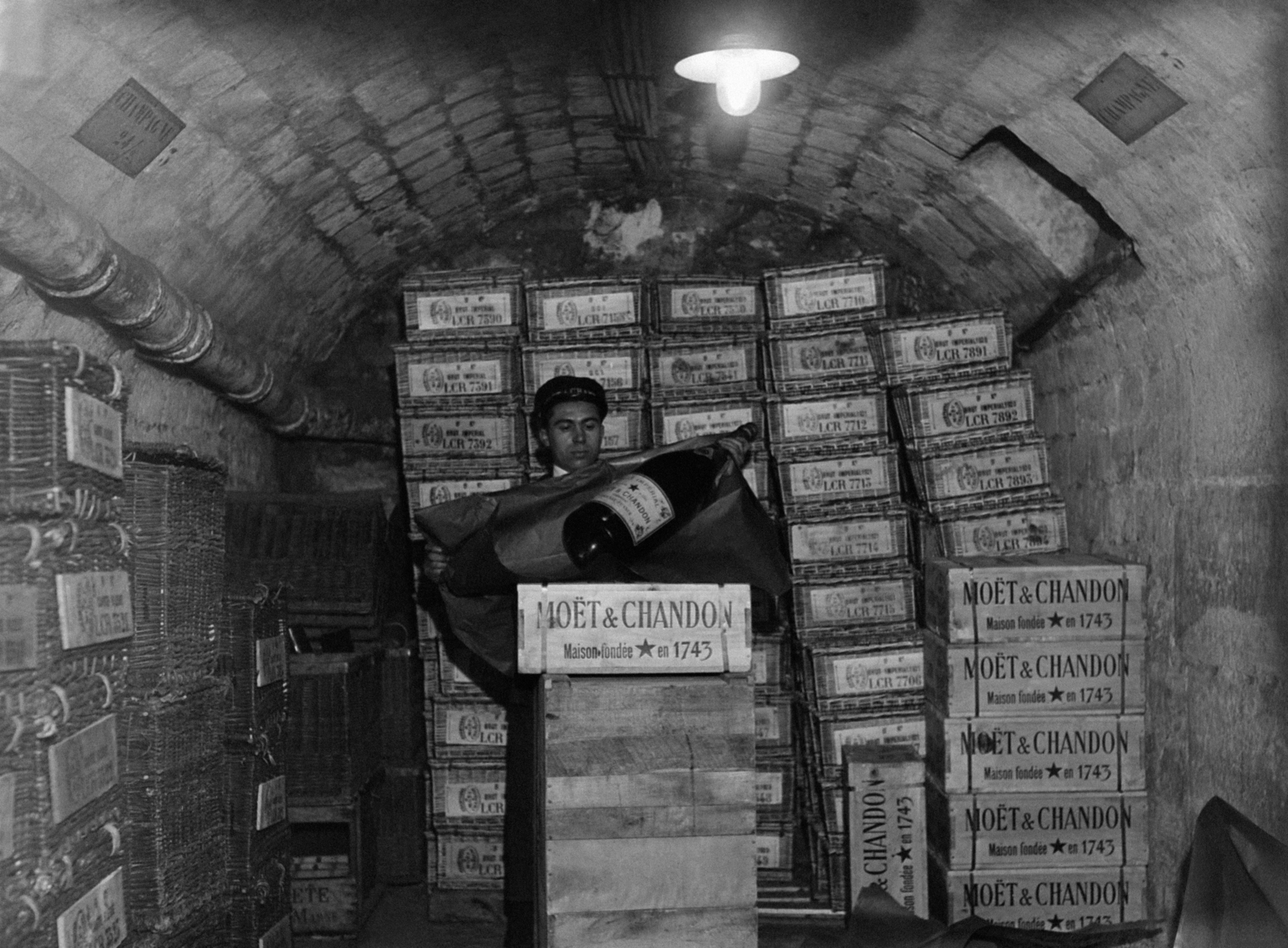

Klaebisch set a nearly impossible demand of 400,000 bottles per week to be sent back to Germany. Count Robert-Jean de Vogüé, the head of Moët & Chandon, led other Champagne makers and pushed back against the order, forming the Comité Interprofessionnel du vin de Champagne to help mitigate and protect the interests of the region.

De Vogüé, himself a member of the Resistance in Epernay, was eventually arrested by the Gestapo in November 1943 on the charge of obstructing trade demands. He was sentenced to death, a charge never commuted by the Germans, and sent to the Ziegenhain concentration camp. De Vogüé was to survive the war, barely, after contracting gangrene in his right pinky finger. Denied medical attention, de Vogüé, without anesthetic, cut off his own finger with a shard of glass to stop the infection. British paratroopers eventually liberated the camp in May 1945.

During the five years of occupation, the French hid what wine they could and mislabeled others –– with some of nation’s most illustrious winegrowing region’s plastering the label “poison” on their best vintage bottles. In one incident, retold in Wine & War: The French, The Nazis & The Battle for France’s Greatest Treasure, a troop of German soldiers seized what they believed to be a cache of eau-de-Santenay gin. It was, in fact, a laxative.

The fight to preserve one of France’s greatest treasures in World War II was met with creativity and courageousness on the part of vintners. In Wine & War, Claude Terrail, owner of the Restaurant La Tour d’Argent relates that “To be a Frenchman means to fight for your country and its wine.”

On May 7, 1945, almost fittingly, the German High Command surrendered in Reims, the capital of the Champagne region.

So pop the bubbly, thank de Vogüé, and have a happy New Year.