In his posthumously published memoir War Years With Jeb Stuart, Confederate Lt. Col. W.W. Blackford noted that, in September 1862, “The truth was that their [Union] cavalry was afraid to meet us….[U]p to this time the cavalry of the enemy had no more confidence in themselves than the country had in them, and whenever we got a chance at them, which was rarely, they came to grief.”

This wasn’t typical postwar bluster. As Blackford, who served under Stuart from June 1862 until Stuart’s death in May 1864, fully realized, the bulk of the Army of the Potomac’s cavalry during the Maryland Campaign was of mediocre quality. It was not the troopers’ fault, but rather the culture in the army at that time in tending to consider cavalry not as an offensive weapon but as couriers, escorts, orderlies, and such. The result, Stephen Starr writes in The Union Cavalry in the Civil War, was a “crippling effect on the discipline and training of units that had not been together long enough to acquire much of either, or to develop the esprit de corps that is an essential ingredient in the success of any military organization.”

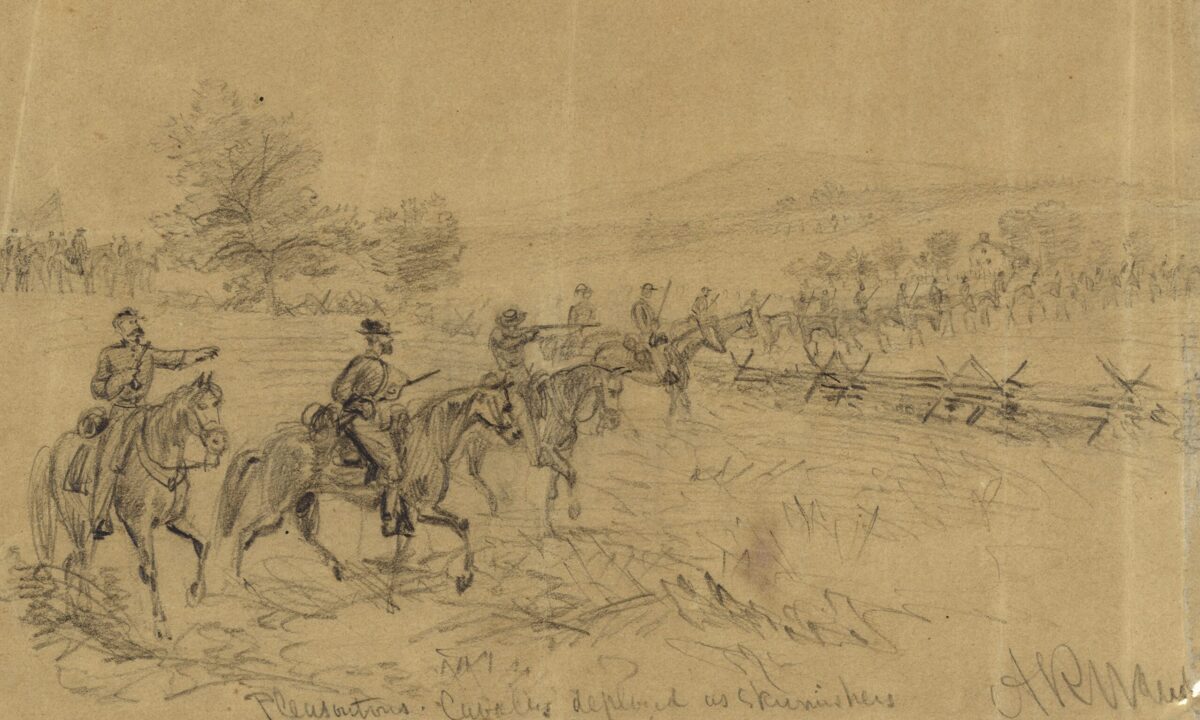

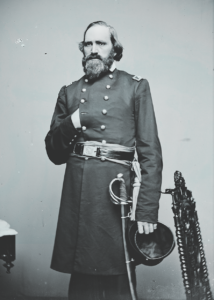

Although George McClellan took a step toward improving that at the campaign’s start by concentrating most of his cavalry in a division under Maj. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton, it was deceptive. Forty-six companies, the equivalent of four regiments, were still detached as escorts, couriers, provost guards, and such—dispersed across the army. Many regiments in the division lacked carbines and were armed only with pistols and sabers. Even among those who had been issued carbines, few had training in fighting dismounted, which was the most effective way to employ the weapon. Although Pleasonton’s cavalry would fight bravely, they were routinely bested or stymied by Stuart’s cavalry in engagements at Maryland locales such as Poolesville, Frederick, and Middletown.

But two of Pleasonton’s regiments, the 8th Illinois and 3rd Indiana, were well-equipped and trained, with good leadership—and on September 15, the 8th Illinois gave Stuart’s cavalry a taste of what to expect when the Federal mounted arm gained greater proficiency.

When the Army of Northern Virginia retreated from South Mountain to Sharpsburg on September 15, Brig. Gen. Fitz Lee’s cavalry brigade drew the assignment as rear guard. Lee placed a section of horse artillery east of the village of Boonsboro in a commanding position along the National Turnpike and posted the 3rd Virginia Cavalry, mounted, on either flank as support. Dismounted skirmishers covered the front, and the 4th and 9th Virginia formed in column in rear of the artillery. Early that morning, the Confederate troopers watched Union infantry descend the mountain along the turnpike. Lee conducted a textbook rear-guard action, skirmishing with the Federals and lobbing some shells, forcing them to deploy and slowing their advance. Having achieved his mission, Lee slowly withdrew toward Boonsboro, sending his guns into town followed by the 4th and 9th Virginia and then the 3rd Virginia, contesting each step.

The process was relatively routine, but Lee’s troopers were exhausted from a night in the saddle, and when the 4th and 9th Virginia reached Boonsboro, the men were allowed to dismount and stretch their legs or snatch some sleep. The 3rd Virginia, meanwhile, skirmished its way back to the village. The pressure increased when the Federals advanced the veteran 5th New Hampshire Infantry to the front, but the Southern horsemen seemed unfazed. Their mobility enabled them to keep the enemy soldiers a comfortable distance away.

The terrain, however, kept Lee’s troopers from detecting that Union cavalry had joined the pursuit: six companies of the 8th Illinois under aggressive Colonel John F. Farnsworth, who likely was unaware just how strong a Confederate force he faced. His men trotted up next to the 5th New Hampshire; placing himself at the head of the column, Farnsworth ordered a charge.

Caught by surprise, the mounted and dismounted skirmishers of the 3rd Virginia tumbled back into Boonsboro. Standing beside his horse in the village, 9th Virginia Lieutenant George W. Beale heard a rapid firing of pistols and carbines, then shouts of “Mount! Mount!” from his commander, Colonel W.H.F. “Rooney” Lee, who had witnessed the fervent Union charge. It was too late. “Retreating at full speed,” Beale wrote, the 3rd’s mounted rear guard collided with “our already confused columns [and] the street became packed with a mass of horses and horsemen, so jammed together as to make motion impossible for most of them.”

Some of Boonsboro’s staunchly Unionist residents added to the chaos by firing from windows into the milling mass of horsemen. The Illinois troopers pressed the attack and, as one Confederate conceded, “in the twinkling of an eye” the entire brigade deteriorated into a mob, with each man “rushing wildly back along the rock ribbed Pike, as if he was determined he would win the race.” By this point, the 5th New Hampshire had joined the fray, adding to the mayhem.

Crowded together, the Rebels were driven pell-mell to the north, churning up clouds of dust that obscured piles of rocks placed along the road for repairs. Riding upon them, Southern troopers and horses were hurled to the ground. His horse shot from under him, Rooney Lee was sent sprawling beside the road “dazed and helpless.”

Elements of Fitz Lee’s Brigade rallied to temporarily check the relentless pursuit, but when the Federals brought up a horse artillery battery and began shelling the grayclad enemy, the rout was renewed. “This was an awful day for our Brigade,” observed one of Lee’s officers.

How had six companies of cavalry routed three regiments? It was an action Blackford discreetly ignored when he assessed combat between Union and Confederate cavalry in the Maryland Campaign. Several factors accounted for the lopsided success: The 8th Illinois had achieved complete surprise; the Confederates were overconfident and couldn’t imagine they would be challenged by Union cavalry; and, because of this, Fitz Lee had allowed his regiments to crowd too close together in Boonsboro so that when the 3rd Virginia was driven in upon the others, maneuverability was lost. Casualties were likewise lopsided: at least 44 Confederates killed, wounded, or captured as opposed to only one Federal trooper killed and 23 wounded.

Although the Boonsboro clash was relatively minor, it was a harbinger of things to come in 1863, when Federal cavalry achieved the same proficiency the 8th Illinois had shown in September 1862.

Scott Hartwig writes from the crossroads of Gettysburg.

This article was originally published in America’s Civil War magazine.