PICTURE THE LAST AGONIZING HOURS of a man wrongly condemned. The painful regrets over a promising career cut short; a final appeal for pardon, denied; the heart-wrenching letters to loved ones and friends, never to be seen again. From his solitary cell, a decorated U-boat captain pours the final expression of his torment into sketches of his impending death.

How could it come to this—that a talented and committed U-boat captain, having survived the horrors of submarine warfare, would meet an ignominious end at the hands of fellow men in uniform? The scapegoat of a perverted justice system, Oskar Kusch would go down in history as the only German U-boat captain to be executed for daring to speak out against Hitler and his regime.

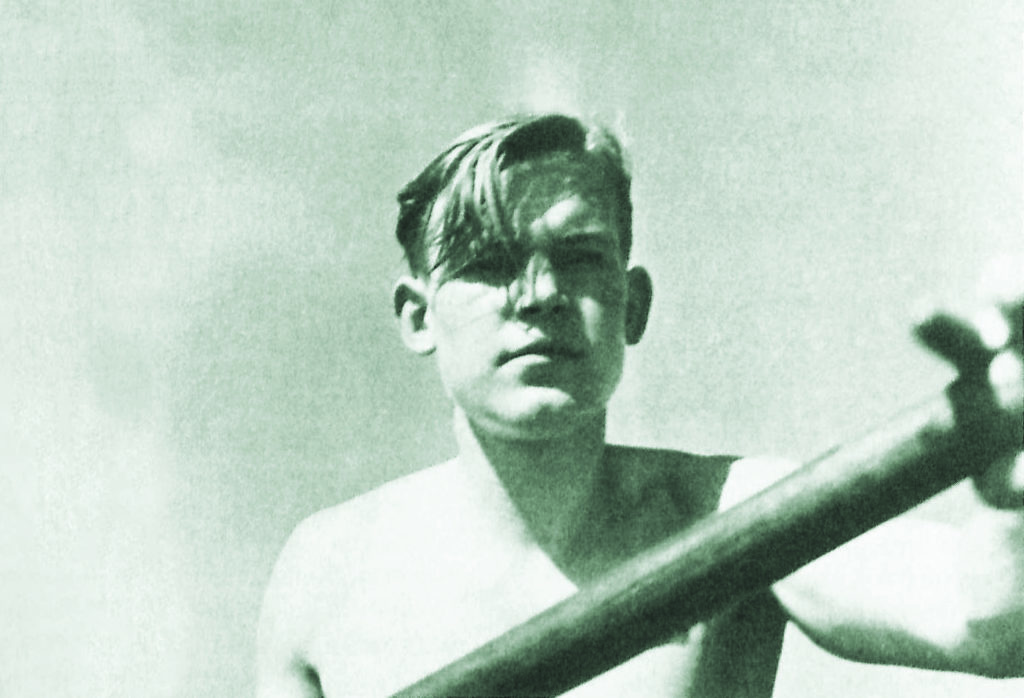

Oskar-Heinz August Wilhelm Kusch, born on April 6, 1918, was the gifted only child of a wealthy family in Schöneberg, an upper-class neighborhood in southwestern Berlin. His father, Heinz—the director of a large insurance company—was a World War I veteran, but also a member of the Freemasons, whose secret rituals and freethinking traditions later drew reprisals from the Third Reich. An intelligent, sensitive youth with an athletic physique and a flair for water sports, Oskar enjoyed a liberal upbringing that shielded him from the worst excesses of Nazification after 1933.

As a boy, Kusch joined the Bündische Jugend, an alliance of youth groups inspired by the International Boy Scouts. His club embraced the teachings of classical art, literature, and philosophy, planting the seeds that would inform his refined views as an adult. In his teens, Kusch started showing what would become a lifelong tendency to thumb his nose at Nazi orthodoxy: after the Hitler Youth absorbed the Bündische Jugend in 1935, Kusch quit but continued to attend clandestine meetings of his old organization. This landed him on a register of “politically unreliable individuals” with the Gestapo, Germany’s notorious secret police. As a result, although he had graduated high school with honors in autumn 1936, Kusch failed to obtain a police certificate of good political standing and proof of “desirable personal conduct” from the Gestapo—a criterium for entering higher education and many civil professions.

This problem evaporated when the 18-year-old was drafted for military service in April 1937. Thanks to his experience as a sailor in civilian regattas, Kusch was advised to join the Kriegsmarine, the German navy. To his great relief, he discovered that the navy, in particular among the branches of the German armed forces, was considered a place of political independence, where liberal ideas were tolerated and one could escape persecution from the “Brown Shirts” (Hitler’s stormtroopers, whose uniforms became synonymous with the regime’s brutality). As Kusch would soon discover, that didn’t keep Nazi ideologues and spies from joining the navy’s ranks, U-boat forces included.

AFTER TWO YEARS of naval instruction, Kusch served on the light cruiser Emden, but he soon grew bored with his duties and applied for a transfer to train as a submarine watch officer—a post he regarded as far more exciting. In June 1941, he was appointed junior watch officer on U-103, which went on to become the U-boat with the third-highest tonnage sunk in World War II. There his commanders showered him with praise. Although he was only 23, Kusch’s ensuing swift rise through the ranks was not unusual at the time, amid the German military’s growing appetite for officer material as the war intensified. He was promoted to sub-lieutenant and awarded the Iron Cross, concluding his training and returning to U–103 as senior watch officer in August 1942. Onboard U-103, Kusch and his crewmates felt free to criticize the government in informal discussions, a U-boat tradition promoted by the boat’s captains—first Werner Winter and later Gustav-Adolf Janssen, whose own comments often suggested that both had reservations about the Nazi Party line.

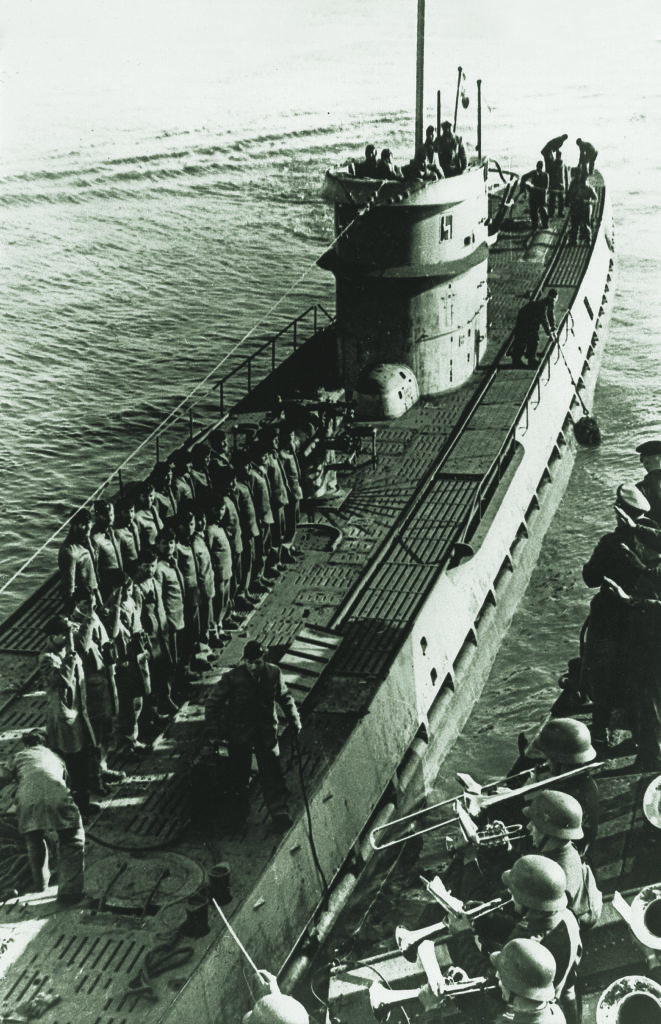

Kusch’s first U-boat command was from the French port of Lorient in February 1943 on the aging U-154. Lorient was the Germans’ largest and most active U-boat base, the hub of its Western command, directing hundreds of craft in the Atlantic and beyond. Though skeptical of what he saw as Germany’s outmoded submarine technology and the shrinking chances of the Axis powers winning the war, Kusch rose to the challenge; his first combat tour enjoyed moderate success, sinking one ship and damaging two others.

That same year marked the turning point in the Battle of the Atlantic. In May 1943 alone—soon to be called “Black May” by U-boat men—41 German subs would be lost at sea, compared to 85 in the whole of the previous year. As the Allies began asserting their supremacy over the ocean, Karl Dönitz, the grand admiral of the German navy, reluctantly ordered an end to U-boat attacks on convoys in the North Atlantic, gradually discontinuing his wolf pack operations. The halcyon days of the “Happy Time,” when marauding German subs could sink vast tonnage of enemy ships almost at will, would be gone forever.

When Kusch took the helm of U–154, he meant to run his boat like U–103: a well-oiled fighting machine whose highly professional crew bandied about political views within the bounds of traditional comradeship—that is, with relative impunity. He would strive to promote a critical assessment of Nazi myths among his officers, assuming that truth and logic carried more weight than party lies.

That assumption proved to be terribly wrong.

Kusch’s first task as captain was to give an introductory speech to his crew and meet with the officers of U–154 individually. Among them, Ulrich Abel, a 31-year-old lieutenant of the naval reserve, was the new senior watch officer. A trained lawyer and former lower court judge, Abel had been a Nazi Party functionary in Hamburg before joining the merchant marine. He had considerable experience as a seaman and had skillfully commanded a minesweeper in the North Sea, but he had never served on a U-boat.

To Kusch’s dismay, when he sat down with Abel, the lieutenant dispensed with a rundown of his naval qualifications and instead gushed that final victory was near, thanks to the Führer’s military genius. Next, engineer Kurt Druschel made a point of highlighting what a wonderful job he had done as a Hitler Youth group leader. The ideological lines were being drawn.

Just before his U-boat set off in March 1943, Kusch issued a controversial order: that the Führer’s portrait in the officer’s mess be removed and displayed in a less prominent spot. “Take that away, we’re not in the business of idolatry here,” the new captain said. In its place, Kusch, a talented artist, hung a drawing he had made of a schooner at sea, probably the training ship Gorch Fock on which he had served.

Kusch made no secret of his anti-Nazi stance, and his attitude quickly became known to everyone on the cramped sub despite the repeated urgings of his friends to watch his tongue. “What do the German people and a tapeworm have in common?,” he quipped to his crew. “They are both surrounded by a brown mass [a reference to the brown shirts] and in constant danger of being evacuated.” The German term for “evacuated,” abgeführt, also means “arrested and taken away.”

But the decisive break between Kusch and his pro-Nazi officers arguably occurred in the early hours of July 3, 1943. As U–154 was returning from a combat tour in the Caribbean, it joined up with U–126, also headed back to France. In the Bay of Biscay—by this time a perilous patch for German U-boats—an enemy plane suddenly appeared and dropped depth charges, prompting both subs to crash-dive.

U–154 escaped unscathed, but its compatriot wasn’t as fortunate. Ominous cracking noises soon reverberated in the depths, suggesting U–126 had been hit and was being crushed by rising water pressure as it sank. Kusch surfaced several miles from the attack site to look for survivors, but the risk of a new air raid prompted U–154 to break off and dive again. It arrived in Lorient alone three days later.

Although flotilla command later deemed Kusch’s actions correct during and after the attack, Abel, who had a close friend on U–126, reproached the captain to his face for not stepping up a rescue attempt. From that moment on, the senior watch officer was “filled with hatred” for his superior, according to Arno Funke, the new junior watch officer and another committed Nazi who had joined U-154 in the mid-Atlantic to replace an outgoing crewman.

In September 1943 Kusch set sail on what would be his final patrol, again to the Caribbean. He was joined by Hans Nothdurft, the boat’s new surgeon, who also took a dim view of Kusch’s anti-Nazi tendencies. U-154 did not manage to approach a single convoy and was targeted in numerous air raids. On the return journey to Lorient, heated arguments ensued between Kusch on one side and Abel, Druschel, and Funke on the other.

When U-154 arrived back at Lorient before Christmas 1943, all officers were invited to a gathering with flotilla commander Ernst Kals, who would pass on holiday greetings from Dönitz. Issued months earlier, but held back by Kals for reasons of morale, the “greetings” contained an ominous message:

Complainers who voice their own personal wretched and miserable opinions and force them openly on their comrades…must be held accountable unmercifully and relentlessly by the military courts for criminally undermining our fighting abilities.

Since the Battle of the Atlantic had turned against the Germans, reports of sagging morale among navy personnel had trickled back to Dönitz. He remembered an armed rebellion that sailors in the German port of Kiel led during the final days of World War I; his tough message was designed, in part, to quash any threat of a revolt. Furthermore, the naval commander in chief had moved closer to the Nazi Party line calling for a total and unquestioning commitment from all servicemen—eroding the very independence the navy prided itself on.

ON CHRISTMAS EVE, as his last task before going on leave, Kusch prepared an evaluation of Abel, who was being transferred to Germany to train as a U-boat commander. Abel’s “thinking and acting are somewhat rigid, inflexible, and often rather one-sided,” the captain wrote, but he added that his officer was nonetheless suitable for U-boat command. Abel was “an average officer with good abilities to get his way,” Kusch concluded, damning his underling with faint praise.

Abel received the captain’s evaluation on January 15, 1944. Long indignant at being subordinate to a “less educated” officer more than six years his junior, Abel seethed when he read the document and quickly wrote a report denouncing Kusch, presenting it the same day to the commander of his U-boat school, Heinrich Schmidt.

Schmidt skimmed over Abel’s 11-point attack, which included the Hitler portrait incident, Kusch’s “anti-National Socialist” attitude, and the captain’s descriptions of the Führer as “insane, megalomaniacal, and pathologically ambitious.” Abel said Kusch claimed he had it from a reliable source that “the Führer often has fits, rants and raves, pulls the curtains down and rolls around on the floor.”

Among the most serious charges, Abel quoted Kusch as saying “Germany’s defeat will in no way be a disaster” and also shared that the captain had warned sailors against government propaganda, claiming it was a Nazi lie that world Jewry aimed to destroy Germany. Furthermore, Abel said Kusch had poisoned the crew’s political views by passing on dangerous ideas from enemy radio broadcasts; for instance, he said the captain had been duped into thinking Allied raids on German cities were primarily against military targets—the Allies’ stated policy—rather than on the civilian population, Berlin’s official version of the truth.

Schmidt urged Abel to reconsider, as a denunciation against a fellow officer could leave a black mark on his own record and, in the wake of Kusch’s evaluation, be construed as spite. Abel, however, was resolute. The case was swiftly passed to flotilla command and declared a “super-secret command file,” a top-level classification that allowed the judges to employ extraordinary means to hurry it along—a rare action.

Upon returning from leave on January 20, 1944, a surprised Kusch was handcuffed at Lorient station and transferred to the armed forces’ jail in Angers, France. As most of the witnesses had already returned to Germany, officials decided to try the case in Kiel, at the upper court of U-boat training command. Kusch arrived in Kiel on January 25 and was placed in solitary confinement. A friend quickly found a defense lawyer, Gerhard Meyer-Grieben, who was willing to take on the case at extremely short notice. He and Kusch were told that the court-martial would take place the next morning, January 26.

THE COURT-MARTIAL, attended by several officers of U-boat admiralty, was a subdued affair. Kusch is said to have been calm and self-assured, and he made no inflammatory statements against the Nazi regime. Several enlisted men of U–154 gave sterling accounts of their captain’s conduct, while officers of U–103, including Kusch’s former captains, Winter and Janssen, stood up for their former officer but could not comment on the matter at hand.

It was the damaging testimony and reports of U–154 hardliners Ulrich Abel, Arno Funke, and Kurt Druschel, along with that of the surgeon, Hans Nothdurft, that decided the case—that Kusch had “undermined the fighting spirit” of his command by spreading a sense of defeatism through his political discussions and by illicitly monitoring enemy radio stations.

“I never talked about the Reich’s defeat in these terms,” Kusch contended. “I also never claimed a defeat was certain.” He added that he only listened to foreign radio stations when the reception of German stations was poor. “I wanted to hear about Berlin,” the young captain said. “Mostly I just listened to music. I discussed the news with the officers.”

It came as little consolation that Abel’s charge of cowardice in combat, based on Kusch’s failed pursuit of a convoy in the spring of 1943, could not be proved and was summarily dismissed.

Oddly, Kusch appeared to do little to defend himself during the proceedings. He rejected his counsel’s suggestion to plead for clemency, believing he could beat the charges. Kusch did not deny his conduct or the statements of which he was accused of making, trying instead to modify them in a way that no longer incriminated him. “My comments about the Führer have been misinterpreted by the witnesses,” Kusch coolly told the court. “We were generally discussing the boundaries between madness and genius. In any case I did not say the Führer was a megalomaniac.”

But Abel and Druschel vehemently opposed Kusch’s attempts to downplay his remarks about Hitler. Even a junior crewman who claimed to have heard nothing of Kusch’s remarks against the Nazi regime still had to admit the accused seemed to reject the Third Reich and its institutions.

By the end of the afternoon, the court had heard enough. Kusch, the prosecution asserted, had greatly endangered the operational capability of his vessel through his treasonous conduct, thus jeopardizing the lives of its crew. The prosecutor recommended he be jailed for 10-and-a-half years, plus one year for spreading malicious content from foreign radio broadcasts, and that he lose all military and civilian rights.

After just 43 minutes of deliberations, Chief Judge Karl-Heinrich Hagemann and two military assessors emerged with an astonishing sentence: death by firing squad, based largely on Kusch’s remarks about the Führer and the perceived endangerment of Germany’s war effort.

The ruling set in motion the only execution of a U-boat captain in the history of the German navy. (Another U-boat commander, the hapless Heinz Hirsacker, had been convicted of cowardice in 1943, but took his own life before the execution could be carried out.)

Kusch showed little emotion upon hearing the verdict. Dressed in full uniform, the condemned man rose and saluted the court, barely having time to shake the hands of two U-154 crewmen before being yanked away by military police.

After the court-martial, Winter, Kusch’s first commander on U-103, wrote a long personal letter to Dönitz pointing out that Abel’s charges relied heavily on hearsay and rumors, and that the case should be retried. Dönitz replied that he could not change regulations and that the matter, in any case, had been taken out of his hands—Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring would have the final say on Kusch’s punishment. A pardon seemed increasingly unlikely.

Janssen, who had been Winter’s successor and a one-time personal aide of Dönitz, even traveled to France in a last-ditch attempt to convince his former boss to appeal to Göring to overturn the ruling. The grand admiral reluctantly agreed to review the matter, saying he would speak to Kusch and “look deep into his heart and test him thoroughly.” Evidently, Dönitz forgot all about his promise after returning to Germany, as he never contacted Kusch and made no effort to review the case.

As Kusch meanwhile languished in prison, everyone but his family and closest friends abandoned him. From his letters, some of which were intercepted by naval command and never delivered, it was clear Kusch believed he would be spared—but the death sentence was confirmed by Göring and the head of Wehrmacht high command, Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, on April 10, 1944. On May 11, Kusch was informed that he would be shot the next morning. To the very end, he proclaimed his innocence. In one last letter to his father, a desperate Kusch wrote: “Life could have been so beautiful, but a senseless fate has destroyed everything.”

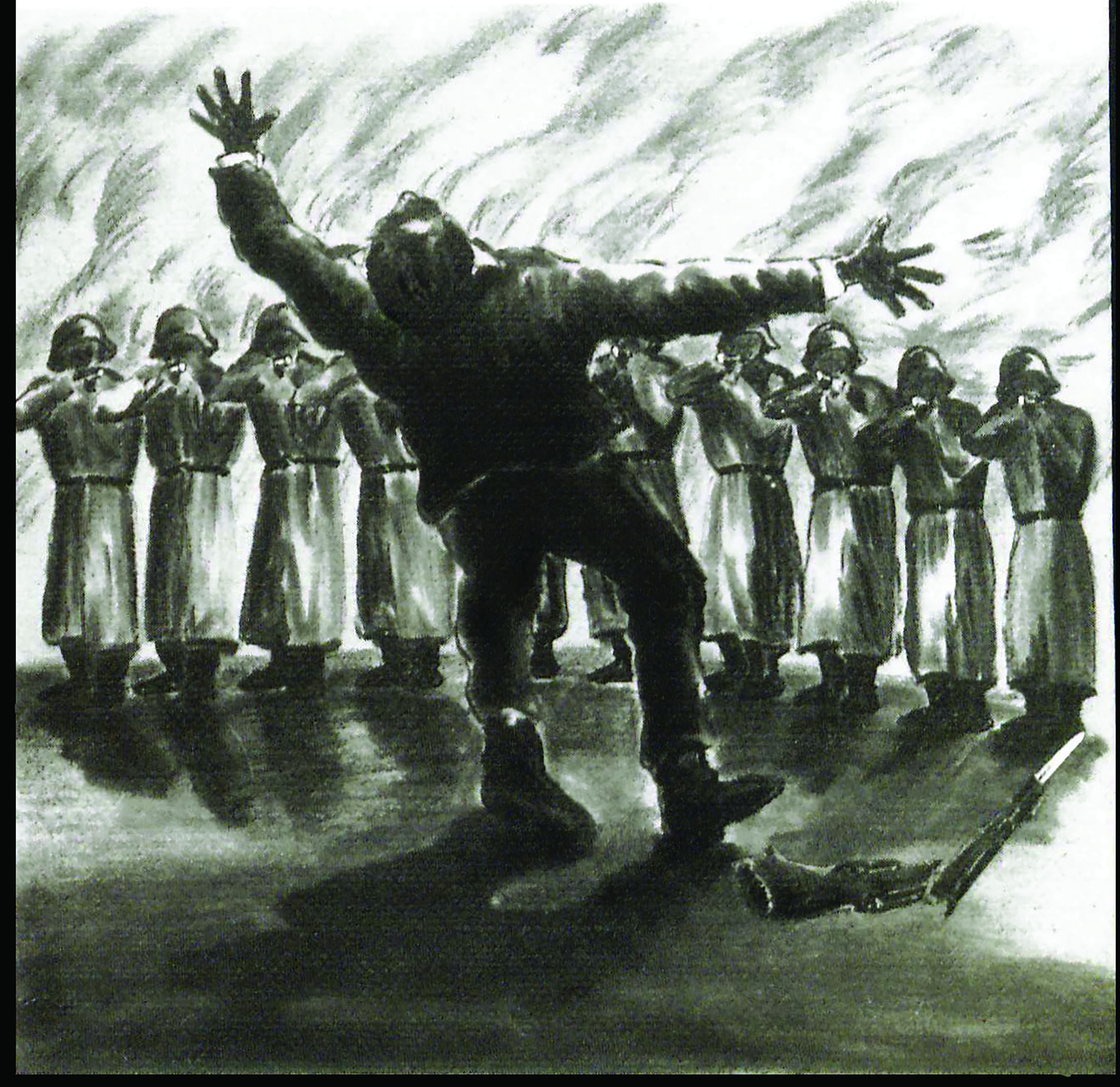

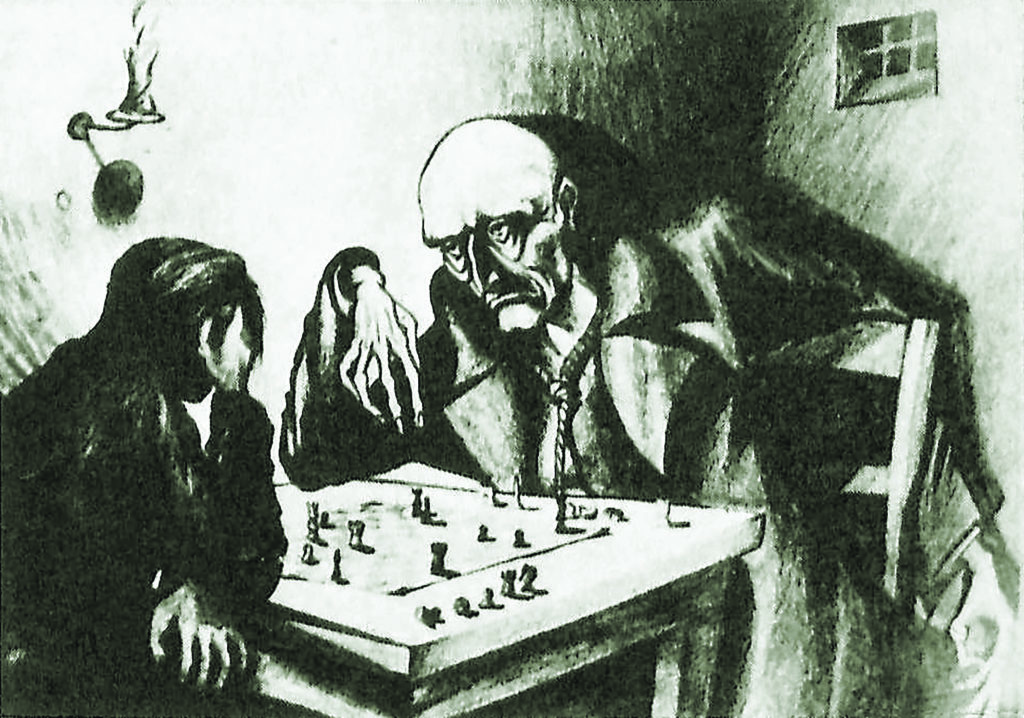

Kusch expressed these last dark hours in stunningly evocative artwork that would be published after the war, including his nightmare of the firing squad that awaited him.

As Germany’s naval apparatus buckled to the will of the Nazi regime, Kusch, an opponent of Hitler but a self-proclaimed defender of the fatherland, was led from his prison cell and shot at a canalside firing range at 6:32 a.m. on May 12, 1944. He was 26.

His chief nemesis, Abel, would briefly fulfill his dream of commanding his own sub, U–193. Ironically, it was lost with all hands in April 1944, three weeks before Kusch’s execution.

AFTER THE WAR, Kusch’s father set about trying to clear his son’s name. In 1949–50, Karl-Heinrich Hagemann, the judge who had convicted Kusch, was tried in Kiel alongside the two military assessors who had approved the execution. The sentence was deemed to have been lawful under the code of justice of Nazi Germany, and Hagemann and his cohorts were acquitted. “Just following orders” was still a good-enough defense.

Erich Topp, a celebrated U-boat ace who served as an admiral in postwar Germany, was among those who tried to reverse Kusch’s wartime conviction, but he ran up against diehard elements in the naval veterans’ movement. Other officers noted that earlier in the war, Kusch’s remarks and any Allied radio monitoring by a U-boat captain would have been considered nothing more than minor irritants and dismissed. For instance, Jürgen Oesten, a U-boat commander and Knight’s Cross recipient, admitted that in 1941 he, too, had listened to enemy radio broadcasts while at sea. Word had made it to Kriegsmarine brass, but Dönitz had buried the issue.

In 1996, Kusch’s case returned to the public eye thanks to the painstaking work of historian Heinrich Walle, who had evaluated the wartime files and published a seminal book on the U-boat captain. Two years later—more than half a century after the end of hostilities—the German national parliament, the Bundestag, annulled all Nazi criminal rulings that had violated basic principles of justice in order to maintain the Third Reich. Much of the prosecution’s attack on Kusch, for instance, relied on hearsay from members of the U-boat crew, strongly suggesting the case would have never gone to trial had the draconian Nazi legal system not been in place.

Oskar Kusch was finally exonerated.

In 1998, the street leading to the canalside firing range in Kiel was renamed in Kusch’s honor, with a memorial dedicated to the enlightened U-boat captain who had dared to openly resist Hitler.

The inscription reads:

His name stands for the many victims of the unjust National Socialist state who lost their lives here and elsewhere. Their deaths are a warning to us all. ✯

This story was originally published in the December 2019 issue of World War II magazine.