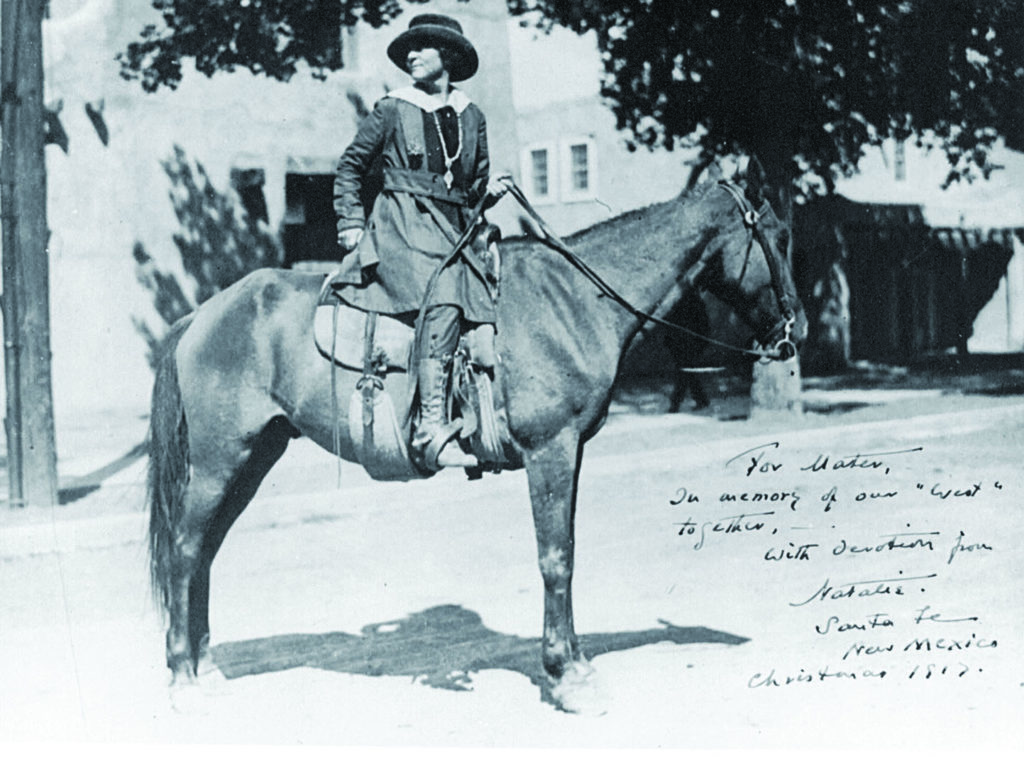

During the summer of 1903, President Theodore Roosevelt had fled Washington, DC’s swelter. He was vacationing at Sagamore Hill, his family home at Oyster Bay, New York, 25 miles east of New York City, when in burst Natalie Curtis. In the Manhattan socialite’s wake stepped a Yavapai Indian chief. The chief, whose name was Pelia, was carrying an enormous handwoven basket, a gift for the president. Curtis had brought Pelia to plead his tribe’s case.

The Yavapai, an Arizona tribe, had a longstanding grievance. In the 1870s, Pelia told Roosevelt, federal authorities had uprooted the Yavapai from a reservation in the Verde River Valley to another far southeast. On their harsh 180-mile winter trek, some 100 Yavapai had died. Federal officials promised that maintaining good behavior would get them back to Verde River. Instead, the Yavapai had spent 25 years docilely living alongside other Apaches distinctly different in culture and temperament. The Yavapai felt that they could never truly be themselves until they were in a separate community and back on the land that traditionally had been their home. Now their former reservation was full of squatters, the Indian leader told the president.

“Chief, tell your people that the White Chief will see that they have justice,” Roosevelt replied. He had the band’s former reservation cleared of squatters, and by 1905 the Yavapai had returned to the Verde River Valley.

To gain the intimate access that made this correction possible, Curtis, 28, had used her family connections. The Curtises and Roosevelts were of an ilk; Natalie’s family summered next door to J. West Roosevelt, a cousin of the president’s. An uncle of hers was an ally of Roosevelt’s in the campaign to reform the civil service.

That bold intrusion on a vacationing president was typical of Curtis, who refused to live by the narrow expectations of the Victorian world into which she had been born in 1875.

“In this moment of resurgent feminism, she is an inspiring reminder,” novelist Ellen Heath wrote in a 2018 online essay. “Natalie Curtis was one of the earliest, daring women who stepped bravely into the New World at the beginning of the 20th century.”

Natalie Curtis’s family, in patrician parlance, was not rich but merely well-to-do, though still gilded by lineage. Father Edward, a society physician, was a Son of the American Revolution and a descendant of two presidents of Harvard. Edward Curtis’s grandfather had represented Rhode Island in the U.S. Senate and served as chief justice of that state’s Supreme Court, and Edward’s father had been president of New York’s Continental Bank. Dr. Curtis, hailed by The New York Times as “one of the most widely known physicians in this country,” had assisted on Abraham Lincoln’s autopsy. He was the Equitable Life Assurance Society’s medical director. When not treating affluent patients, he was pioneering in photomicroscopy—taking pictures through a microscope. He and his family inhabited the Greek Revival mansion on Washington Place in Greenwich Village that Edward, oldest of four sons, had inherited from his late father. Natalie attended Brearley, the highly selective secondary school for girls.

The Curtises, who had ties to Transcendentalism, a 19th-century socioreligious movement that rejected conformity and urged each person to find a role in the world, saw themselves politically as Progressives. But progressivism was one thing. Sending a daughter to college was another, and the Curtises declined to educate Natalie beyond 12th grade. However, she had talent at the piano and as a composer was impressive enough for her parents to enroll her at the National Conservatory of Music, whose faculty included some of New York City’s premier musical luminaries. Observing the young woman’s progress at composition and playing, teachers encouraged her to study in Europe. She did, first in Paris and then at Bayreuth, Germany. Hand strain and doubts about her talent kept her from the stage. G. Schirmer published songs she had composed using as lyrics well-known poems, but Natalie Curtis decided her life’s work was not to be strictly musical.

Asthma led Curtis to a career. When her brother George, an asthmatic, took doctors’ advice and relocated to Arizona for its dry climate, Natalie followed. Traveling the Southwest, she met journalist Charles Lummis, an advocate for American native peoples. Lummis, who lived in Islata, a Pueblo village on the Rio Grande in New Mexico, fiercely opposed federal policies that for decades had discouraged, even banned, Indians from maintaining and practicing their traditions, such as living by the assumption that land belonged to all, constituting a shared resource everyone had a duty to preserve.

Through Lummis, Curtis met many Southwestern Indians. Their music enthralled her. Before meeting Indians, she wrote later, she “was not prepared to find a people with such definite art-forms, such elaborate and detailed ceremonials, such crystallized traditions, beliefs, and customs.” Indian women’s corn-grinding songs and lullabies entranced Curtis, as did men’s Flute Dances and songs associated with traditional kachina dolls. She decided she would transcribe tribal melodies and lyrics and introduce them to mainstream America. In 1903, armed with a $38 Edison recorder and a supply of blank 25-cent wax cylinders on which to record, Curtis set up shop on the Hopi Moqui reservation in northern Arizona, hoping to be able to collect corn-grinding songs.

The task was not easy. Reservation officials were pressuring, even forcing, Indian children to attend a school that barred the Hopi language, the singing of traditional songs, and the painting of bodies. The school’s white superintendent, Charles Burton, zealously enforced federal policies designed to muscle Indians into joining white society. School officials even sheared young Indians’ uncut hair—a particular outrage because Indians saw hair as a symbol of power and identity, the human equivalent of the sweet grasses gathered for incense and seen as the hair of Mother Earth. Hopi men historically had twisted their locks into elaborate figure-8 buns, but by 1900 more typically were wearing their hair loose to the shoulders. “Their long hair is the last tie that binds them to their old customs of savagery, and the sooner it is cut, Gordian like, the better it will be,” Burton wrote.

In this environment, Indian women hesitated to perform for Curtis out of fear that she would snitch to reservation authorities. “Are you sure you will not bring trouble upon us?” a chief asked.

“A friendly scientist on an Indian reservation advised me that if I wished to continue my self-appointed task of recording native songs, I must keep my work secret, lest the school superintendent in charge evict me from the reservation,” Curtis said. She persisted, gaining Indian women’s trust by approaching them as a fellow performer, singing songs she knew in return for hearing theirs and accurately transcribing their material without using her recorder.

From its first days, the United States had struggled with how to treat indigenous people. Most Native American tribes had been fighting forever among themselves for resources, land, and power; European colonization and Manifest Destiny added better-armed Whites to that mix. As early as 1790, Congress had passed the NonIntercourse Act, meant to keep the peace on the frontier by establishing Indians’ right to occupy—though not legally own—their tribal lands and banning individuals from claiming that land. The federal Bureau of Indian Affairs began overseeing tribes’ welfare in 1824.

That stewardship, emphasizing coexistence, was initially benign. But soon, around 1830, the government began removing Indians from their traditional lands and relocating them to reservations—parcels reserved for a given tribe or band. The U.S. Army began to deploy troops to subjugate tribes responding with hostility to White settlement, leading to more treaties and more reservations, a pattern shattered by the 1887 General Allotment Act, identified with primary sponsor Senator Henry L. Dawes (R-Massachusetts). Instead of allowing tribes to coexist with the American mainstream, the government now meant to assimilate Indians, if need be by force.

The Dawes Act ordered reservations defined by treaty broken up and subdivided. The Bureau of Indian Affairs was to assign individual Indian families plots to own and work, as White settlers had done in taking title to portions of federal allotments of western lands. Indians, of course, did not believe in private land ownership. To counter and extirpate this profoundly anti-capitalist sentiment, the government undertook to eliminate Indian culture. Even the Indians Rights Association, formed by well-meaning Whites in 1882 to pressure Washington to treat indigenous people with more dignity, had as its aim “to bring about the complete civilization of the Indians.” Differences in social structure and tradition, as well as historic animosities and rivalries, kept tribes from allying in their own collective interest until the mid-1900s.

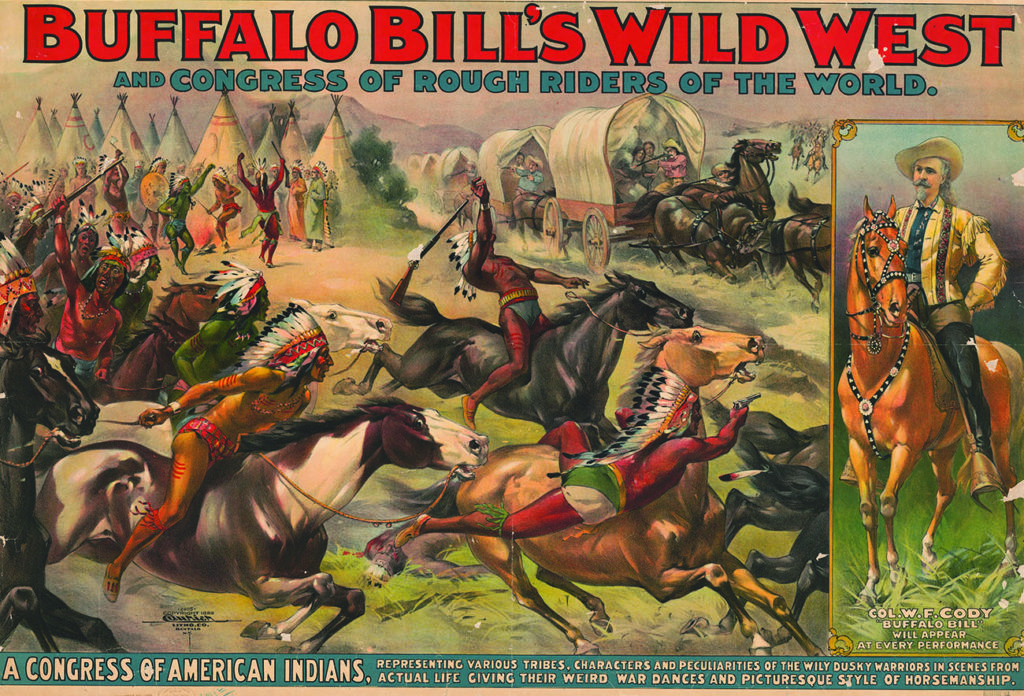

This was the churn into which Natalie Curtis was inserting herself. Most anthropologists then studying Indian folkways were seeing themselves as preserving a mode of living doomed to extinction. Mass culture had reduced the Indian to a sideshow performer in Wild West extravaganzas such as those promoted by former buffalo hunter Wild Bill Cody. Curtis wanted to keep Indian cultures alive and vibrant on their own terms. Her mission, she said, was to fight for “the right of the American to be himself, to express his own ideas of beauty and fitness.”

Curtis’s surreptitious but successful venture into recording corn-grinding songs led her to conceive of a broader, deeper effort documenting Indian culture—a project too large to pursue on the sly. Emboldened by President Roosevelt’s decision to aid the Yavapai, she wrote to him urging that he replace Indian school superintendent Burton. “The Indians dislike him,” she told the president. “He is generally considered inadequate to his position.” Unmoved by Curtis’s complaints about Burton, Roosevelt responded with significantly more enthusiasm to a request from Curtis that he arrange for her to obtain untrammeled access to Indians so she could study their cultures in the open.

The package of materials that Curtis provided to Roosevelt, which included one of her song transcriptions, had pointedly couched her proposal’s potential impact in cannily prescient market-driven terms.

“If the arts of the Indians of the Southwest are fostered intelligently who knows but what, in time, Arizona may become distinctively famed for her pottery and silverware, in the same way that Venice is for her glass and Dresden for her porcelain,” Curtis wrote. Roosevelt responded to her tactically astute overture with an invitation to pay a call at the White House, where during a meeting Curtis pushed her agenda, arguing that to “educate a primitive race the would-be educators should first study the native life in order to preserve and build upon what is worthy in the native culture.”

Roosevelt immediately got on board.

“Within hours of their meeting Roosevelt provided her with the necessary letters to research on Western reservations free from official interference,” Curtis biographer Michelle Wick Patterson writes.

Extolling Curtis’s arguments to Interior Secretary Ethan Allen Hitchcock, the president ordered Hitchcock to bring Curtis and Indian Affairs Commissioner William Jones together and to “do everything possible to develop the Indians’ artistic capacity along their own lines.” With brashness and fervor, Curtis had spurred a 180-degree shift in official policy on Indian culture. By 1913, the Interior Department’s Indian education branch had a supervisor of music. “The preservation of Indian music may not have occurred had it not been for the efforts of Natalie Curtis,” music historian Lori Shipley says.

Besides brass, Curtis had timing. Roosevelt once had held Native Americans in the same ill regard many Whites did. “I don’t go so far as to think that the only good Indians are dead Indians, but I believe nine out of ten are,” he said in an 1886 speech. “And I shouldn’t like to inquire too closely into the case of the tenth.” However, he was capable of changing his mind and positions. By the 1890s, Roosevelt, now a U.S. Civil Service commissioner, was insisting Indian candidates get preference when government Indian schools were filling administrative and faculty vacancies. The country’s most famous adoptive Westerner encountered Curtis’s effusive advocacy as his views on government’s role toward Indians evolved.

There was little political risk in TR’s new platform. By the time Curtis bearded him at Oyster Bay, Roosevelt had already seen a clear advantage to embracing Indian causes. Whites were becoming less fearful of Indians. This made siding with tribes less of a political liability and, in one way, a political advantage. An 1890 U.S. Army massacre of some 150 Sioux at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, had effectively ended tribal violence toward Whites. Additionally, Roosevelt, elevated to the White House in 1901 by William McKinley’s assassination, was looking to a presidential run of his own in 1904. The Republican ticket needed more votes among Roman Catholics, whose church had sent missionaries to convert Indians to Rome for generations. The church and the federal government had been partnering since 1874 to educate Indian children; schools run by the church’s Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions enrolled some 2,500 students. Helping Indians could draw more Catholics to the Republican Party.

With multiple factors inclining Roosevelt to endorse her project, Curtis needed only money. As it had accomplished regarding presidential access, her family’s social network put largesse within reach. During her trip east in 1903 Natalie described her grand idea to investment banker George Foster Peabody and heiress Charlotte Osgood Mason. Each saw Curtis’s work with Native Americans dovetailing with their good deeds.

Peabody, after running Edison Electric and overseeing its merger into General Electric in 1906, had retired to devote himself to social causes and politics. His charitable activities included funding a Young Men’s Christian Association branch in Columbus, Georgia, and donating the land on which the University of North Carolina at Greensboro was built. He was a trustee and underwriter of historically Black Hampton University, in Hampton, Virginia, where he established an enduring collection of works on African American history. Mason came from old New York money on her mother’s side and had married physician Rufus Osgood Mason, of similar caste and circumstance. Upon his death in 1903, her fortune and philanthropy greatly expanded, with a focus on Black writers.

Once Peabody and Mason agreed to contribute to Curtis’s project, she went into the field. In Maine she transcribed war, dance, and love songs of the Passamaquoddy and the Penobscot. In St. Louis, Missouri, she recorded Navajo, Klalish, and Crow elders brought to the World’s Fair for “Anthropology Days.” In late 1904, she began a four-month tour of Western reservations, relying on charm to bring off recording sessions but also occasionally paying for performances by Winnebago, Cheyenne, Sioux, Hopi, Pima, Navajo, Yavapai, and Apache singers. Her usual approach, she wrote, was to explain to a chief that “the olden days were gone; the buffalo had vanished from the plains; even so would there soon be lost forever the songs and stories of the Indians.” She explained that “the White friend had come to be the pencil in the hand of the Indian” to immortalize that heritage.

Along with cataloging her recordings, Curtis distilled the works she had collected into a single print volume aimed, unlike existing academic works on Indian culture, at ordinary readers.

In 1907, Harper Brothers published The Indians’ Book, whose 500-plus pages presented songs and stories Curtis had collected from 18 tribes, augmented by her notes on her travels and explanations of how the contents illustrated each tribe’s unique ways. Curtis refused to Westernize the material. The result awed readers. “The music of the Indian has before no such record,” a reviewer for the Omaha Daily Bee wrote. “No emotion is absent, no expression wanting.” That year, The Indians’ Book led Dial magazine’s list of recommended Christmas gift books; “a revelation,” the entry read. The Washington, DC, Evening Star review began, “It appears to us that to overpraise this work might well be deemed impossible.” In a rave, a New York Times reviewer called the volume “the most intimate portrayal of Indian life and nature that has yet been attempted.”

Curtis sent copies to influential friends, including TR, who replied, “These songs cast a wholly new light on the depth and dignity of Indian thought, the simple beauty and strange charm of the vanished elder world of Indian poetry.” Subsequent editions of The Indians’ Book featured the president’s remarks as a frontispiece. The volume, which is still in print (see p. 59), remains the standard work on Native American song.

Natalie Curtis amplified her advocacy for Indian culture by tirelessly promoting her own activities. She lectured, performing Indian songs and poetry in settings her personal connections opened, such as the homes of conservationist Gifford Pinchot, Union Pacific President E.H. Harriman, and prominent suffragist Eva Ingersoll Brown. She appeared at the 25th-anniversary dinner of the New York League of Unitarian Women, and before members of the Washington, DC, Society of Fine Arts. In an era when ethnographic writing was generally the province of little-known, arcane journals, Curtis was writing about Indian culture for mainstream magazines Harper’s, The Outlook, and The Craftsman. Her articles cast Indians in a romantic light that went far to erase the once-ubiquitous image of indigenous peoples as backward savages.

A proto-folklorist, Curtis argued that “the music of America is not found in universities and schools but out in the great expanse of territory that stretches from the Atlantic to the Pacific Oceans, and from Canada to Mexico.” At George Peabody’s prodding, she widened her focus to African American culture and in 1910 began recording songs from Black students at Hampton Institute. In 1918, a year after marrying artist Paul Burlin, she began publishing what would be the four-volume Negro Folk-Songs. After World War I the couple moved to the French capital so Paul could pursue an interest in Expressionism. On October 23, 1921, a speeding motorist struck and killed Natalie on a Paris street. She was 46.

On for the Long Haul

That The Indians’ Book is still in print and still enlightening readers is perhaps the clearest testament to the importance of Natalie Curtis’s work. Her book introduced many musicians to Native American music’s complexity and sophistication. For instance, Italian composer/conductor/pianist Ferruccio Busoni used tunes in the book as the basis for his “Indian Fantasy,” premiered in 1915 by the Philadelphia Orchestra under Leopold Stokowski, and “Red Indian Diary,” a still-performed suite of short piano pieces. In 1950, New York Times book review editor Donald Adams, encountering The Indians’ Book, recommended it to readers as offering “great value to amateurs in American ethnology and to anyone who wishes to learn something about the true nature of our predecessors on this continent.” A reader review on Amazon.com praises The Indians’ Book as “proof that the social engineers and bureaucrats did not kill the spirit and culture of the rightful inhabitants of this land.” GoodReads.com recommends it as “an American treasure and classic that preserves and honors not only Native American tribes but the compassion and vision of Natalie Curtis herself.” (To hear Curtis’s recordings, visit bit.ly/NatalieCurtisRecords)

Curtis’s less direct—but arguably more important—impact lay in the extent to which her efforts on behalf of Indians opened paths for subsequent scholarship. Ethnographers, archeologists, and linguists, mostly employed or funded by the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Bureau of American Ethnology, amassed at the Smithsonian Institution an archive of Indian songs, stories, and details on customs and practices. This occurred because Indians had assurance that they would not in the name of assimilation be persecuted for sharing their culture. Theodore Roosevelt distilled his young friend’s impact in the October 1919 issue of The Outlook, describing Natalie Curtis Burlin as one “who has done so very much to give Indian culture its proper position.” —By Daniel B. Moskowitz

This story was originally published in the August 2021 issue of American History. To subscribe, click here.