At just a few minutes past 6:30 p.m. on January 28, 1999, Alan Beith, a member of Parliament representing the constituency of Berwick-upon-Tweed in the north of England, rose to address his colleagues to begin what is known as an adjournment debate. Members of Parliament may set any issue as the topic of such a debate, and an appropriate government official is required to attend, listen, and respond. In this case, John Spellar, Britain’s undersecretary of state for defense, was on hand.

It was a clear, unseasonably warm evening in London, the sidewalks crowded with Tube-bound commuters. The front page of the Evening Standard announced Ford Motor Company’s purchase of Volvo and displayed the smiling face of Julia Roberts, the actress. But inside Parliament, as Beith spoke, this routine Thursday in the last year of the 20th century faded away, and a terrible moment from 59 years earlier came into focus. The existential worries of wartime replaced the incidental concerns of peacetime, busy London dissolved into a frigid Norwegian Sea, and one of the great and inexplicable disasters of Britain’s desperate fight against Germany took center stage.

“On the afternoon of 8 June 1940, two German battle cruisers, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, sighted a wisp of smoke on the arctic horizon,” Beith began. “Two hours later, the carrier HMS Glorious and its two escorting destroyers, Ardent and Acasta, had been sunk.” Beith went on to describe how more than 1,500 lives had been lost, qualifying the incident as one of England’s worst naval disasters of World War II.

The Mysteries of the Sunken Ship

The Glorious and its escorts had been caught while returning to Scapa Flow in Scotland following England’s failed bid to save Norway in the early days of the war. In the rock-paper-scissors game of that era’s naval warfare, aircraft carriers reigned supreme—until they came under the guns of an enemy battleship, in which case they were utterly helpless.

So it was for HMS Glorious.

“Why was Glorious returning home independently of the main convoy?” Beith asked. Several of his constituents, he said, were pushing him to get answers. “Why was she so badly prepared? Why was her air power not used even for reconnaissance? Was there not sufficient intelligence about German activity in the region to suggest that Glorious should have been in a much greater state of readiness?”

History—and especially the history of World War II—shapes day-to-day life in Britain more than it does, for example, in the United States. But the intense emotions stirred up by the sinking of the Glorious are unusual, as is the fact that more than 50 years afterward, the incident merited heated debate in the heart of the nation’s government. Many of Beith’s questions went unanswered in 1999 and remain unanswered today.

The story of the sinking of the Glorious is shot through with drama and subplots. The ship had been the setting for the daring recovery on its deck of land-based Hawker Hurricane fighters, even though the planes had no arresting hooks and their pilots had no carrier training.

But the Hurricanes—and most of the pilots—would go down with the ship a day later. The pilots were among the hundreds of men who perished in the Arctic waters because it took 24 hours for word of the sinking to reach the Royal Navy’s high command.

The one ship that might have saved them, a cruiser just 50 miles away, did not deviate from its course because it had on board a passenger whose safety was paramount: King Haakon VII of Norway, who was accompanied by his entire cabinet.

The Admiralty has long maintained—as Spellar did again that day in 1999—that the Glorious was sent home on its own because its mission was complete and it was low on fuel. Perhaps those were two of the reasons it was lost. Another is without a doubt the inexcusable and almost incomprehensible lack of precautions taken. But in recent decades an even darker theory has taken hold.

“The truth may lie in a different direction,” Beith intoned ominously, after dismissing the contention that it had been low on fuel. “HMS Glorious may well have become detached from the greater safety of the convoy because of a serious breakdown in relations among her senior officers. She was an unhappy ship.”

“An Unhappy Ship”

The Glorious was an ungainly looking thing, with a flush flight deck and towering bridge island grafted onto what had once been the low-slung form of a battle cruiser. In its fierce original incarnation, during World War I, it saw action in the Battle of Heligoland Bight in 1917 and was present when the German fleet surrendered to the Allies. It was converted into an aircraft carrier under the terms of the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922.

As with similar conversions in other navies, the result was successful but awkward. The ship’sflight deck did not extend to the bow; rather, the Glorious retained the classic fo’c’sle of the battle cruiser it had once been. Gunports and platforms were cantilevered here and there; it all looked a bit makeshift. One officer referred to the ship, affectionately it seems, as a “flat-topped old barmaid.” It lacked the clean lines of a modern, purpose-built carrier, such as the Ark Royal, which had joined the Royal Navy in 1938.

The Glorious was in the Mediterranean when the war broke out and was soon dispatched to the South Atlantic to search for the German pocket battleship Graf Spee. It returned to the smooth, sunny Mediterranean before being assigned to help protect Norway from German invasion. The rough, slate-gray Arctic was a dramatic change for the 1,200 men crowded in the ship’s labyrinthine steel interior of hangars, galleys, cabins, and endless corridors, the thrum of the engines and the motion of the sea constants.

“A carrier is a rum sort of a place, with its windswept flight-deck, its great grey cliff of steel up to the bridge and its bays of guns,” Ronald “Tubby” Healiss, a member of a Royal Marine antiaircraft crew, would write in his memoir, Arctic Rescue: A Memoir of the Tragic Sinking of HMS Glorious. He described the ship’s “miles of low-roofed passageways and a thousand coamings to stumble over, its brine-sprayed great hull and all the time its sickly sweet oil stench.”

The Daredevil Captain

Up in the bridge atop that great cliff of steel was the Glorious’s captain, Guy D’Oyly-Hughes. Before assuming command, he had been the executive officer of its sister ship, HMS Courageous, and was something of a legend in the Royal Navy. D’Oyly-Hughes had begun his career as a submariner in World War I, during which he single-handedly—and famously—swam ashore with a raft of explosives, blew up a portion of the Constantinople–Baghdad Railway, and then swam back to the sub. Photographs from the early 1920s, when he acted out this feat for newspaper photographers, show a beaming daredevil, bearded and stripped to the waist, happily embracing his central-casting looks. He was said to be a favorite of Winston Churchill’s.

D’Oyly-Hughes also had a temper, which often seemed to be aimed at Commander J. B. Heath, the director of air operations, and Lieutenant Commander Paul Slessor, Heath’s number two. Petty Officer Dick Leggott, the pilot of a Gloster Sea Gladiator fighter, recalled a strange introduction after he’d touched down on the flight deck for the first time. “We were taken up to the bridge to meet the captain, D’Oyly-Hughes, and he said, ‘Well, I’m very pleased to see you. You’ll be more use to me than those two over there.’ ” He gestured to Heath and Slessor. “We thought, ‘Oh, God, what’s going on here?’”

In a 1999 BBC documentary, D’Oyly-Hughes’s daughter, Bridget, recalled not only her father’s thrill at commanding an aircraft carrier but also his exacting standards. A man who blew up railroads and engaged in other solo Lawrence of Arabia–type exploits, she said, expected the same level of commitment, daring, and even showmanship from his underlings.

“He was delighted because he’d been so keen on flying, he’d learned to fly, he thought flying mattered, and it brought aeroplanes and the sea together in one command,” she said of her father’s appointment to be captain of the Glorious. As for a possible feud with his air staff, “he would have been impatient of any lack of enthusiasm on their part,” she said. “He was always impatient of lack of enthusiasm.”

J. B. Heath, interviewed years later, described being constantly overruled and “stamped on” by the captain. And he offered a radically different opinion of D’Oyly-Hughes’s ability, saying that he seemed to have a “total lack of knowledge of air affairs.”

The coming disaster would suggest that Heath’s assessment was correct.

A Fateful Quarrel

The Glorious, the Ark Royal, and their escorts arrived off the coast of Norway on April 24, 1940, flying off planes that had been loaded by crane in Scotland to the airfields where they would be based. Their arrival meant that the Glorious’sown complement of Sea Gladiators and Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers, both biplanes, would be reduced. Nonetheless, those that made the trip were kept busy.

“The clatter of arrester wires was going all the time as the Swordfish came back after nonstop two-hour patrols,” Healiss recalled. “It was pretty sure things were hotting up. You could tell that, too, by the mechanical hammerings coming all night from the hangars, where some of the Swordfish were struck down for maintenance as the other fighters were operational.

“The racket seemed to fill the whole ship, and I didn’t sleep too well.”

Between April and June the Glorious would make five round trips from Norway to Scapa Flow, with fuel concerns keeping it in the battle zone for relatively short periods, usually a few days. (It was known in naval parlance as a “short-legged” ship.) On May 26, its second-to-last visit, the Glorious safely flew off 18 Hawker Hurricanes of 46 Squadron that flew from the ship to land bases. It was on this mission that things came to a head between the captain and his air staff.

The Glorious was ordered to also send its Swordfishes, now only five, to land bases, where they were to attack German positions. Heath refused, saying the objectives were vague and this was not the proper use of naval aviation. In the wardrooms the pilots had been lamenting the fact that their light naval aircraft were outclassed by the Luftwaffe’s heavier, more powerful, and faster land-based fighters. Moreover, Heath argued, the assignment would leave the ship defenseless. “Do you risk matériel and men for five poor old aircraft trying to bomb a target that they don’t know even exists?” he recalled asking. “It was the most crazy high heroics that you could think of.”

D’Oyly-Hughes was furious at Heath, and the two men had a row. Interestingly, the pilots sided with the captain, not their air commander. “We thought an effort perhaps should be made to do something and help the army,” Leggott would later recall. When the ship returned to Scotland, Heath was placed under arrest, taken ashore, and charged with “cowardness in the face of the enemy.” He would await court-martial on dry land. Slessor, his number two, remained on board.

By early June it was obvious that Norway was lost and that the 18,000 British personnel there, along with their planes and other equipment, needed to be brought back to England to protect the homeland. The nightmare of Dunkirk was unfolding simultaneously. Operation Alphabet was launched to get everyone out. The Glorious and the Ark Royal steamed back to Norway, taking up station off Narvik.

To Save the Planes

Stranded ashore were the Hurricanes of 46 Squadron that had been flown in just days earlier. There would be no time to load them aboard with cranes, nor would the Glorious be risked by docking, and they didn’t have the range to fly from Norway to Scotland. The choice was to burn them or try to land them on a carrier at sea. The Hurricanes didn’t have arresting hooks to catch on flight deck cables, and their pilots had no carrier training. But their commander, Lieutenant Kenneth Cross, was determined to save his planes.

Ground-crew members surmised that placing sandbags in the planes’ tails and slightly deflating their tires might slow them enough when they hit the deck to keep them from shooting off the bow. While this had never been tried before, the Hurricane pilots decided to give it a go.

The Glorious was chosen because the elevators from its flight deck down to its hangar were large enough to accommodate the planes, whose wings, unlike those of naval aircraft, did not fold. So it was at 2 a.m. on June 8 that, one by one, the Hurricanes arrived over the Glorious and the other British ships. They circled, lined up, descended, and squealed to a stop on the flight deck, the pilots giving the brakes all they had, as the Glorious raced into the wind at full speed of 30 knots to give the fliers a few crucial meters of extra runway. None of the planes came even close to overshooting; they all stopped two-thirds of the way down the deck.

“We were rather proud of ourselves,” Cross recalled. He jumped out of the cockpit, relieved like the others to be safely out of Norway, and was taken up to the bridge to meet D’Oyly-Hughes. The captain’s words of welcome? “What took you so long?” He offered no handshake.

Roughly 30 minutes later the carrier requested permission to depart without the fleet, and it was granted by L. V. Wells, the vice admiral in charge of carriers. The Glorious and two destroyer escorts—the Ardent and the Acasta—sailed for home. Immediately after the war the Admiralty would maintain that the trio was sent in advance of the task force because the Glorious was running low on fuel. But in 1968 the captain of another destroyer, HMS Diana, would be quoted as saying that he had seen the carrier communicating via signal lamp with the Ark Royal, the flagship, asking for permission to proceed ahead to Scapa Flow for Heath’s court-martial.

In any event, the tiny squadron sailed into the still-bright Arctic summer night.

German Wolves of the Sea

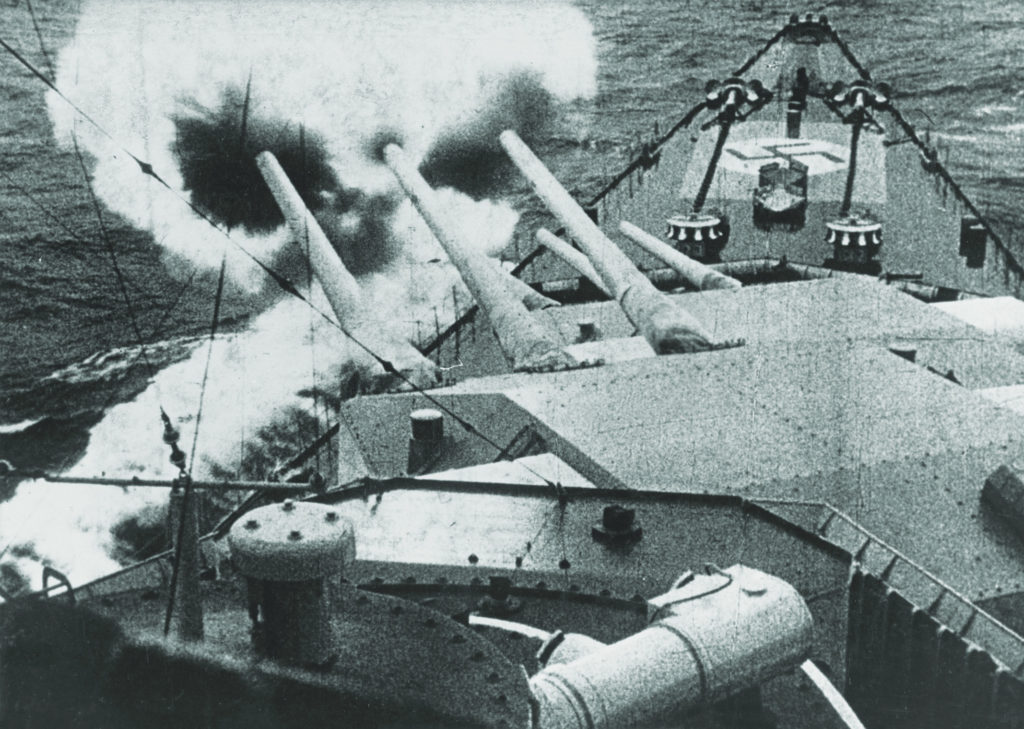

The German battle cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau were great wolves of the sea—32,000-ton state-of-the-art capital ships, both sporting three main turrets, each with three 11-inch guns. Their raked bows slid down in sheer, unbroken, almost elegant lines to their sterns. Their superstructures were modernist towers of bridges, compass platforms, range finders, and even early radar. It is hard to imagine two ships less like Britain’s “Old Barmaid.”

Throughout April and May, either as a pair or with others, the Scharnhorst and the Gneisenau had trolled the ocean, harassing British ships and, on at least one occasion, getting chased by Royal Navy battleships. After returning to port for repairs, the ships set sail on June 4 under the command of Admiral Wilhelm Marschall, who, like D’Oyly-Hughes, had been a submariner during World War I.

Marschall was under orders not to engage enemy warships but, rather, to find and sink retreating merchant ships and troop transports. The gray wolves raced through the Denmark Strait and into the Norwegian Sea, attracting the attention of at least one Allied coastal observer.

British code breakers at Bletchley Park also noted increased German navy radio traffic suggesting a possible breakout and relayed the intelligence to the Admiralty. The warnings were ignored.

Improbably, the German battle cruisers had a motion-picture crew onboard.

At 3:46 p.m. on June 8, the Glorious and its escorts, reaching a point several hundred miles off the coast of Norway, had turned south on a heading of 205 degrees for Scapa Flow. They were in the “fourth state” of readiness, steaming at 17 knots with 12 of the carrier’s 18 boilers lit, zigzagging to throw off any lurking German U-boats. No planes were in the air for reconnaissance, nor were any ready for takeoff. Nor was there a lookout in the Glorious’s crow’s nest. It was a calm sea with 6.5-knot winds—modest by Arctic standards—with unlimited visibility.

Leggott was having a cup of tea. Cross was in his bunk. Healiss was on the flight deck. “The sea was calm and deep blue,” Healiss would recall. “A good June day for the Arctic.”

The Enemy Closes In

At 4 p.m. two strange ships were sighted on the Western horizon on a course heading of 330 degrees. The Ardent was ordered to investigate and sped off toward them as a call came down to the Glorious’s hangar to arm the five Swordfish with torpedoes and bring them up on deck. Twenty minutes later a call came for “action stations.”

German lookouts had already spotted the British ships. The battle cruisers turned toward their quarry and revved to top speed; Marschall was not going to waste this opportunity. On they came, with the faster Gneisenau slowly overtaking the Scharnhorst. The Ardent issued a challenge with its signal lamp: Identify yourselves. At 4:27 p.m. they answered by opening fire.

Hit repeatedly, the Ardent fired a spread of torpedoes and turned around. One barely missed the Scharnhorst. The Acasta raced in behind, and both destroyers started belching smoke to shield the carrier.

It wasn’t enough. The battle cruisers trained their main batteries on the Glorious, with the Scharnhorst firing its first salvo at 4:32 p.m. from 16 miles away. The Gneisenau followed 12 minutes later.

“I was having my tea when I saw through the port hole splash, splash, splash,” Leggott later recalled. “I said, ‘What the hell is that?’ ” His memory might have been slightly off because records indicate action stations were called before the first salvo landed, but his words nonetheless capture the utter surprise with which many on the British ships greeted this sudden and violent intrusion on their peaceful journey home.

Healiss found himself pushing through a crowd of sailors to grab his sea boots, helmet, and a few bars of chocolate from his locker—he knew from experience that he might not eat for hours—before reaching his gun station.

Cross and his fellow Hurricane pilots mustered at their evacuation stations. Cross’s station was just over the stern beneath the aft end of the flight deck. “I assumed it was a practice drill, having been through many,” he said. But now, as Glorious turned to escape, he could see the attackers on the horizon as “two tiny smudges of smoke.” Distant flashes sparkled.

Scharnhorst’s first salvo had landed about 10 yards away, sending three towering pylons of water into the sky—accuracy that Cross thought “remarkable” considering the distance. He decided to report to D’Oyly-Hughes and see if, as commander of the Hurricane squadron, he could be of service. He made his way up a ladder. “As I stepped onto the flight deck the second salvo hit the ship about 10 yards in front of me,” he said. He finally made it to the bridge, but the “tenseness of the faces,” he said, made it “plain to me that I would be in the way.”

Tenseness can only be an understatement, whether in Cross’s description or in the emotions the officers allowed themselves to display. They were in serious trouble.

Battering the Sinking Ship

The powerful German ships were coming at them from the same direction as the wind, which meant that if the Glorious wanted to launch its torpedo-laden Swordfish, it would have to turn toward the Germans, closing the range even more. That option had already disappeared, however, because the Scharnhorst’s first hit had gone through the flight deck, rendering it unusable, and set the bombers in the hangar beneath on fire, along with several of Cross’s Hurricanes. It also ruptured a steam line, causing a momentary decrease in speed. The fire began to spread.

The Germans had found the range. The next salvo hit the compass platform directly above the bridge. “Plumes of smoke filled the air as I watched in horror,” Healiss wrote. “They’d hit the bridge. At the impact I threw myself on the platform instinctively.”

That shot killed D’Oyly-Hughes and most of the command staff. But for others the ordeal had only barely begun. The German gunners struck the Glorious again and again. One projectile blasted through several decks and hit the engine room, slowing the ship and causing it to turn helplessly in circles.

“This was murder,” Healiss said. “Sudden, blazing dirty murder.”

The now thoroughly engulfed airplane hangar was a “living furnace,” as Healiss put it, and horrors abounded. He saw one of his favorite shipmates confused and walking unsteadily because he had lost a leg.

Film footage taken on the German ships shows mountains of water as high as 10-story buildings falling around the Glorious in the opening minutes of the battle, followed by the frenzied and seemingly panicked defense by the destroyers. Finally, the footage captures the listing, burning hulk of the mortally wounded Old Barmaid, smoke and flames pouring from every opening, its already inelegant lines a shambles.

The Acasta and the Ardent, with their small 4.7-inch guns, each scored a hit on a German ship—with little effect—and the Acasta struck the Scharnhorst with a torpedo, killing 51 men. It was a spirited and courageous defense that drew praise years later from German sailors, but in the end, hopelessly outgunned, both destroyers were sunk.

Glorious went down at 6:10 p.m. The German ships sped off, leaving more than a thousand men in the sea.

The Sinking

The temperature of the water was 34 degrees; the men of the Glorious traded scorching heat for bitter cold. Healiss belly-flopped into what felt like concrete. Before he and the others went over the side, they were calmed by the officers walking through the flame and smoke, patting the backs of the young sailors and marines, some of whom could not swim. “C’mon, lads, don’t panic now. Get in line.”

Any hope of a quick rescue faded as night fell, though the sky remained bright, and the next day dawned as clear as the last. The men bobbed in the current, most treading water, some in the few half-swamped lifeboats and launches that had broken free from the Glorious.

Leggott recalled hanging on to a piece of rope with another man and asking if he was all right. “He said, ‘Yeah,’ and with that he died.” He described how others would simply put a hand up, as if to say goodbye, and then slip away.

Cross remembered excruciating thirst, and how the sea was dead calm, and how he could see several fathoms straight down. Healiss made it to a waterlogged launch with 20 others, many of them Royal Marines like himself, who at first sang heartily, “Roll out the barrel, let’s have a barrel of fun.”

After a night and a day and another night, however, he was the only one left alive.

The Glorious had managed to get off one or two Morse-code action reports, but whether they were picked up or understood remains a matter of dispute. A notation in the log of the cruiser Devonshire records that it had received a report as the Glorious was being shelled, but the location was believed to be in error. Moreover, the cruiser was under orders to maintain its course for home, and strict radio silence, because the king of Norway and his cabinet were aboard. While the Devonshire could certainly have rescued men from the sea, German battle cruisers lurking in the vicinity could easily have overwhelmed it.

The Germans didn’t consider the one-sided fight to be much of a victory. Marschall was removed from his command because he’d engaged warships rather than troopships.

He’d also used too much ammunition and allowed the Scharnhorst to be badly damaged.

Decades-Long Pain

The British Admiralty didn’t learn of the sinking for 24 hours—and then from a German broadcast. Search planes were finally dispatched. In the end, only 41 survivors were rescued; 1,519 British seamen, naval airmen, and marines died, the nation’s single largest loss of life in a sea action during the war.

In the end, Alan Beith, the member of Parliament, didn’t get many answers that January day in 1999 when he challenged John Spellar, Britain’s minister of defense. Nor did the Naval Historical Branch veer from its long-held position that the carrier had been sent home for lack of fuel. Beith, now a member of the House of Lords, wasn’t surprised. “When government agencies arrive at a view their instinct is often to defend that view unhesitatingly,” he told MHQ in a recent email exchange. “That is often the case on policy issues, and in this case it applied to history.”

Why did the Glorious episode still cause so much pain so many decades later?

“Anyone who has lost a family member in war feels pain, and that pain is even greater if there is reason to believe the death could have been avoided if better decisions had been made,” Beith said. “Then there were all the issues around commander D’Oyly-Hughes’s conduct and the then impending court-martial of Commander Heath, who was vindicated, and Lieutenant Commander Slessor, who was lost in the sinking.”

In recent years, the Naval Historical Branch has given more credence to the theory that D’Oyly-Hughes had decided to leave early to court-martial Heath. But because he died in the early moments of the encounter, his motivations will never be known.

In 2019 Ben Barker, whose grandfather commanded the Ardent, offered a new theory: that the Glorious was dispatched early because it was needed for Operation Paul, a secret but unexecuted plan to mine the harbors of neutral Sweden so that the Germans couldn’t export badly needed iron ore. Barker’s evidence is intriguing, though largely circumstantial, and his investigation garnered some press coverage. The theory would certainly explain why the British government prefers not to discuss the sinking of the Glorious, even today—such an operation would have been akin to an attack on a neutral nation.

D’Oyly-Hughes’s daughter was quoted in the Times of London as saying it vindicated her father, while the Ministry of Defence dismissed the theory. But the truth may not be revealed until 2041, as the sinking of the Glorious is the only British carrier loss of World War II for which the records have been sealed for 100 years.

Perhaps it was the court-martial. Perhaps it was fuel. Perhaps it was Operation Paul. Those are all possible reasons that the Glorious, Ardent, and Acasta were out alone in the Norwegian Sea. It might even have been a combination of those factors. But no one has been able to explain a perhaps more baffling issue: Why was D’Oyly-Hughes, a veteran mariner, so unprepared for action? How could he have allowed his men and ships to put themselves in such a hopeless situation? Cranky or not, he was by all accounts a skilled naval man and, after all, there was a war on.

The answers to these questions may lie not in secret files or documents or long-forgotten memos, but in the very nature of command, of management, and of loyalty and what one might call the “tyranny of experience.”

Unanswered Questions

Glorious had made five round trips without incident. The journey had become routine. And breakouts by German surface ships were relatively rare. Cross believes that even though the captain could fly, he was at heart a classic sea commander, one from a bygone era, and he didn’t fully grasp the 360-degree, round-the-clock nature of modern naval combat. In D’Oyly-Hughes’s view, Cross suggests, the little trio of ships was out of the battle zone and out of danger and sailing home.

Maybe. And it is certainly not the captain’s job to go up to the crow’s nest to make sure someone is up there looking sharp. The captain sets the tone, the degree of readiness, and expects his orders to be carried out. But it doesn’t always work out that way.

In the history of the Royal Navy, there is a storied episode from 1893, when, off Tripoli in the Mediterranean, HMS Camperdown collided with HMS Victoria, sending it to the bottom of the sea with 358 men. The two battleships were on maneuvers and executing a complex course change on orders of Vice Admiral Sir George Tryon, a demanding commander not known to favor the opinions of others. As the ships turned, it became clear that the Camperdown was on a collision course with the Victoria. Still, the ships plunged ahead. At least one junior officer quietly asked the vice admiral if he was sure about his orders, but the junior officer was rebuffed. The commander of the oncoming Camperdown was certain that Tryon would signal a course change at the last second; he assumed Tryon had a plan. He finally ordered the engines reversed. But it was too late. On a clear, calm, and sunny day, the Camperdown’s ram tore into the Victoria’s innards. The ship was gone in 15 minutes. Tryon was among the drowned.

Did D’Oyly-Hughes’s executive staff assume he knew what he was doing when he set the Glorious to the fourth degree of readiness? Or did they simply not feel like tangling with him? This was a man who’d blown up a desert railway by himself and was known to favor initiative and “high heroics” while barely acknowledging the exploits of others. He was a strong and forceful personality vividly remembered decades after his death. He saw loyalty as obedience, and he had gained fatal confidence in his own judgment through decades of successful exploits and service.

Was his personality so strong, his convictions so deep, his wit so biting, that his junior officers were afraid to speak up? If true, this was his greatest failure as a commander. A true leader must have the confidence to create an atmosphere in which divergent views can be aired. Clearly that wasn’t the case on Glorious’sbridge, high atop that great gray cliff of steel.