The Maus that roared and other exercises in megalomania

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]magine a young American GI on the front in Europe in late September 1944. The leaves are starting to change and there’s a chill in the air. There’s a chill on the ground, too. His regiment had faced scant resistance as it worked its way eastward the past few weeks; now the enemy is starting to put up a fight. Coming warily down a hill toward a small meadow, the men in the squad feel a faint tremor in the ground. No one can ever forget his first artillery barrage; all our young GI can do is mutter “Here we go again.”

The shaking grows stronger and the men look at each other in confusion. The ground is trembling, but there is no sound of artillery. Then they hear the clamor of heavy machinery growing ever louder. They all think the same thing: Tiger. The sight of a Tiger tank is unforgettable—a 60-ton monster twice as big as a Sherman and 10 times more frightening.

Somewhere in the woods beyond the meadow the grinding din grows so loud it nearly drowns out the noise of breaking tree trunks. German troops emerge from the forest, so the Americans take cover. As they do, a dark shape appears and someone says, “That Tiger is a lot closer than I thought!”

Then it breaks into the clearing and the GIs realize that it’s not closer—it’s bigger.

It takes the men more than a moment to wrap their heads around this thing that is definitely not a Tiger. It looks like a tank, but the German infantrymen next to it give it scale. It appears as tall as a four-story apartment building and wider than a boxcar is long. It has two guns in its turret that look bigger than the guns on that battleship their troop transport passed last summer. As the GIs stare at the guns, one jerks violently. There is a blinding flash. A split second later, the sound hits them like a freight train.

WERE THIS SCENARIO NOT FICTITIOUS, it would have marked a dream come true for an engineer—you might call him a mad scientist—named Edward Grotte. Grotte really had designed this behemoth weighing a thousand metric tonnes—about 1,100 tons—that our hypothetical GI saw on that hypothetical day in 1944. An imaginative and ambitious weapons inventor, Grotte had become interested in large tanks during World War I, but was part of a generation of German armament designers frustrated in their postwar ambitions by the dictates of the Treaty of Versailles, which denied their fatherland an arms industry.

In the interwar period, the newly formed Soviet Union provided a refuge for many German engineers and manufacturers. Most Russian engineers and industrialists had ties to the former Tsarist government and had fled when the Bolsheviks took power. That left a void the Soviet government wanted to fill to jump-start their industrial future so, taking advantage of the situation the treaty created, they invited Germans to come east. Aircraft manufacturer Hugo Junkers, for example, had designed some of the world’s first practical all-metal aircraft during World War I, but found himself unable to build airplanes in Germany. The man whose name would later be famous for some of the Luftwaffe’s most important aircraft—the Ju 52 transport; the Ju 87 Stuka dive-bomber; the Ju 88 multirole warplane—moved his factory to suburban Moscow in 1922.

Grotte also migrated east, in 1930 (some sources say as early as 1928) at the invitation of the Soviet government. He spent several years designing tanks at Bolshevik Plant 232 in Leningrad while dreaming of his thousand-tonne monster. In the meantime, he designed the multiturret, 112-ton T-42—never produced because the Soviets lacked an engine large enough. When Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933 and repudiated the Treaty of Versailles, Grotte returned to Germany. He found a home in Essen, at the Krupp industrial conglomerate that built everything from warships to artillery to tanks. He reportedly even found a place on its board of directors.

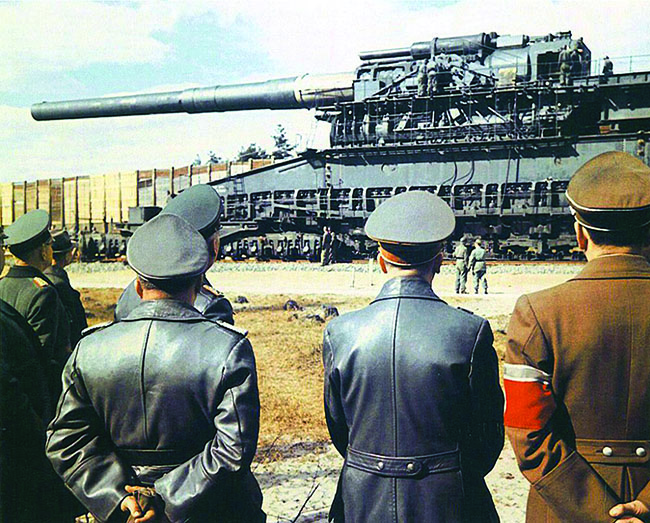

When Germany rearmed, Krupp had a friend in the Reich Chancellery—a very good friend. In 1934 Hitler had embraced Krupp’s scheme for a massive railway gun to be used to bombard the heaviest of fixed fortifications, such as France’s Maginot Line. Named Schwerer Gustav—“Heavy Gustav,” after company chairman Gustav Krupp—it had a bore of 800mm (31.5 inches) and could hurl a nearly eight-ton shell 30 miles. Two were actually built; one was used in the siege of Sevastopol in the summer of 1942. Never mind the enormous gun took hours to load and fire.

Edward Grotte, too, had a friend in Berlin, for Hitler was—dare we say—crazy about large tanks. Wehrmacht doctrine called for smaller, faster tanks—the ones that put the blitz into blitzkrieg—but Hitler believed that, as with warships, the bigger the better.

“What are you after?” the Führer had asked Albert Speer, his minister of Armaments and War Production, in the spring of 1942 during their discussion on how to meet the threat posed by the superior Soviet T-34 medium tank. “The faster ship has only one advantage: to utilize its greater speed for retreating.…It’s exactly the same for tanks. Your faster tank has to avoid meeting the heavier tank.”

With a sympathetic patron to indulge his dreams, Grotte’s thousand-tonne thing began to take shape on the drafting vellum at Krupp, and he completed preliminary drawings by December 1942. The company designated the tank Projekt 1000 because of its weight and named it Landkreuzer (Land Cruiser) because it seemed like a warship. They even picked warship armament—a dual-gun turret with a pair of 280mm (11-inch) SK C/34 naval guns, like those used in the battle cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau (although the turrets on those ships each had three such guns). An improved version of the SK C/28 naval gun, the SK C/34 was capable of hurling a 700-pound shell 25 miles. The armor was also like that of a warship—more than 14 inches thick on the forward part of the turret. They even planned to power this tank with 8,400-horsepower marine diesel engines like those Krupp used for U-boats.

GROTTE WAS NOT ALONE in appealing to the Führer’s fascination with big tanks. Today we know Ferdinand Porsche, a brilliant pioneering automotive engineer, for his compact sports cars and recall that, in the 1930s, he had been the designer who realized another of Hitler’s pet projects. Hitler had envisioned a small automobile that anyone could own, and it was Porsche who created the “Peoples’ Car” or, in German, the Volkswagen. The rest, as they say, is history.

Yet Porsche had another side—a tank side. In 1942 Hitler was thinking of a heavy tank, more than twice as large as the standard Panzer III and Panzer IV: a durchbruchwagen—literally a “breakthrough vehicle”—to crash through enemy lines. Porsche, then 67, was one of those who submitted designs in May 1942. He lost out to the Kassel-based firm of Henschel & Sohn, but it was Porsche who named the new Panzer VI the Tiger.

Porsche was down, but not out. The Tiger project had only served to fire his imagination for the gargantuan, and he had something even bigger up his sleeve. As Albert Speer recalled in his memoirs, “By way of pleasing and reassuring Hitler, Porsche also undertook to design a superheavy tank which weighed over a hundred tons and hence could be built only in small numbers, one by one. For security purposes this new monster was assigned the code name Maus. In any case, Porsche had personally taken over Hitler’s bias for superheaviness.”

This extreme durchbruchwagen was originally intended to be named Mammut (Mammoth), but later came to be wryly nicknamed Mäuschen (Little Mouse), which by early 1943 had been shortened to Maus (Mouse). Whether this name was satire or a security obfuscation, as Speer asserts, is not clear.

Porsche had already produced a full-scale wooden mockup of the Maus when the first Tiger tank rolled off Henschel’s production line in August 1942. General Heinz Guderian, the architect of blitzkrieg tactics who commanded panzer units in the conquest of Poland and France as well as in the early victories over the Soviets, was present when Porsche showed the mockup to Hitler. Guderian considered it grandiose.

“The total weight of the tank was supposed to reach 175 tons. It should be considered that after the design changes on Hitler’s instructions the tank will weigh 200 tons,” he wrote in his memoirs. “An intense debate started and, except for me, all of those present found the ‘Maus’ magnificent.”

At 200 tons, it weighed nearly eight times as much as a Panzer III, the ubiquitous standard Wehrmacht tank of the 1939–1941 blitzkrieg campaigns, and at 33.5 feet, it was twice as long. It stood 12 feet high and its armor exceeded the thickness of that found on many warships. Whereas the Tiger mounted an 88mm gun, Hitler specified the 128mm Pak 44 Krupp panzerabwehrkanone (antitank gun) as the main armament for Porsche’s magnificent Maus. When Guderian complained about a lack of secondary armament, Porsche added a coaxial 75mm gun to the main turret, a 7.92mm MG 34 machine gun atop the turret, and an MG 151/20 20mm antiaircraft gun.

And the Maus really was built—with a chassis by Krupp and final assembly at Altmärk-ische Kettenwerk GmbH in the Berlin suburb of Borsigwalde. The first behemoth was delivered by December 1943, with a second Maus completed about three months later.

Had Albert Speer decided to fast-track the Maus program, might the tank have existed in enough quantity by July 1943 to play a role that month in the Battle of Kursk, the war’s largest tank battle?

As we imagined a Landkreuzer on the Western Front in 1944, we can imagine the Maus on the battlefields of the Eastern Front in 1943. There were more than 200 Tigers at Kursk—but what if there had been 200 of Porsche’s magnificent 200-ton pride and joy? One can imagine Soviet 76mm shells exploding harmlessly against nine inches of steel armor and the withering effect of the rounds from its 128mm gun against the Soviet T-34s, as the unstoppable monsters thundered forward, easily crashing through the enemy.

Yet such imaginings dissipate like smoke curling up from a day-old battlefield, for this couldn’t have happened. The Maus was doomed from birth by its own weight. As enthusiastic as Hitler and his sycophants were about the immense Maus, it was so heavy that it pulverized paved roads. Yet when driven off-road, it was prone to sinking in all but very hardpacked soil. If it had made it to Kursk, transported on the massively reinforced flatcars built for it, and if the ground had not been too soft, and if it was able to maintain its top speed of barely 12 miles per hour, it still could not have kept up with other tanks, and its fuel reserves would have been dry in less than three hours.

The Maus was also too big and wide for bridges, so it was compelled to ford rivers. A 26-foot snorkel was designed so it could cross deep rivers underwater—assuming those rivers did not have soft, muddy bottoms that would mousetrap the Maus.

EVEN AS HITLER RELISHED the might of Porsche’s Maus, he looked forward to Grotte’s P.1000 with breathless anticipation. He even personally honored it with the nickname Ratte (Rat), because it was heavier—more than five times so—than a mere Maus.

Meanwhile, the sparks of imagination that crackled within the engineering minds of Grotte’s team at Krupp began to conceive of something even greater. As they worked on their thousand-tonne tank, they asked themselves: why not a Landkreuzer weighing 1,500 metric tonnes—or 1,700 tons? They put ink to paper and created the P.1500, a monstrous Landkreuzer simply named Monster. While the P.1000 design featured a pair of 280mm guns, the P.1500 would use a long-barreled variant of Krupp’s own 800mm Heavy Gustav.

If reality never sank in at Grotte’s aerie in Essen, it did at the armaments ministry in Berlin. Albert Speer realized that if the Maus was impractical on most terrain and impossible on bridges, both the P.1000 and P.1500 would have been ridiculously immobile. One day in early 1943, when the Führer wasn’t looking, he pulled the plug on both projects.

The Maus project, though, continued. Two had proceeded into the test phase and four more were being built in the summer of 1944 when Speer ordered those four to be scrapped. By now, he realized that he must devote the diminishing industrial capacity of the Third Reich to weapons that had a chance of affecting the outcome of the war.

Those first two tanks remained at the big Wehrmacht weapons proving ground at Kummersdorf, about 20 miles south of Berlin, until May 1945. With Soviet troops closing in on Berlin, one Maus prototype, which had a functional turret, was reportedly sent to nearby Wünsdorf to help protect the headquarters of the German High Command. There appear to be no accounts of it having fired a shot. The Germans scuttled it to keep it out of Soviet hands, though the turret remained intact.

Today, the P.1000 Ratte and the P.1500 Monster have become the stuff of legend, remembered in the way we remember fables from another time and place. The original blueprints are apparently long gone, superseded by fanciful artists’ illustrations that have the appearance of science fiction.

In the case of Porsche’s Maus, however, something tangible has emerged from the mists of time. The Red Army had seized remnants of both prototypes in 1945 and shipped them to their top-secret tank proving ground at Kubinka, about 50 miles west of Moscow. The two monster tanks vanished from public view and for half a century were presumed to have been scrapped. Then, in 1992, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Russians opened a tank museum at Kubinka to show off their vast collection of captured and Soviet-era armored vehicles. Among these—a Maus! The single intact turret had been mated with the intact first prototype hull and chassis.

Today, except on Mondays, anyone can travel to Kubinka, pay the equivalent of less than 30 dollars, and visit Porsche’s intimidating Maus, along with hundreds of its stablemates. The Maus rests in an unassuming corner of one of many huge tank garages at Kubinka, ready to be seen and touched—though not climbed upon—as we ponder those days so long ago when visions of land battleships setting sail for the steppes of central Russia filled the Führer’s imagination, and when men like Ferdinand Porsche were there to electrify his dreams.✯

This story was originally published in the August 2018 issue of World War II magazine. Subscribe here.