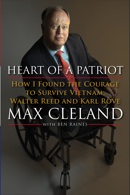

MAX CLELAND suffered severe wounds in Vietnam in 1968, losing both legs and one arm. He spent years recovering at Walter Reed Army Medical Center and the VA Medical Center in Washington, then returned to his home state of Georgia and won election to the state Senate in 1970. He was appointed in 1977, at age 34, to head the Veterans Administration by President Jimmy Carter. Upon returning to Georgia in 1981, he was elected secretary of state, and then went on to win election to the U.S. Senate in 1998. He lost his reelection bid in 2002 after a bitter campaign in which his patriotism was challenged by his opponent. Earlier this year, President Barack Obama appointed Cleland secretary of the American Battle Monuments Commission. His new book, Heart of a Patriot: How I Found the Courage to Survive Vietnam, Walter Reed and Karl Rove, has just been released. Max Cleland spoke with journalist Marc Leepson in Washington, D.C.

MAX CLELAND suffered severe wounds in Vietnam in 1968, losing both legs and one arm. He spent years recovering at Walter Reed Army Medical Center and the VA Medical Center in Washington, then returned to his home state of Georgia and won election to the state Senate in 1970. He was appointed in 1977, at age 34, to head the Veterans Administration by President Jimmy Carter. Upon returning to Georgia in 1981, he was elected secretary of state, and then went on to win election to the U.S. Senate in 1998. He lost his reelection bid in 2002 after a bitter campaign in which his patriotism was challenged by his opponent. Earlier this year, President Barack Obama appointed Cleland secretary of the American Battle Monuments Commission. His new book, Heart of a Patriot: How I Found the Courage to Survive Vietnam, Walter Reed and Karl Rove, has just been released. Max Cleland spoke with journalist Marc Leepson in Washington, D.C.

Writing to Heal

Q. Was there any particular motivation for you to come out with your new book, Heart of a Patriot, now?

Q. Was there any particular motivation for you to come out with your new book, Heart of a Patriot, now?

A. It’s part of my own therapy, my own healing. Those of us who suffer need to talk about it and write about it. I didn’t really have a connection to the suffering of those who have what we now call post-traumatic stress disorder—I call it “post-war stress”—in which you never quite get over what’s happened to you, but you move on. But after I lost the Senate race in 2002, my life collapsed. I went down in every way you can go down. I lost my life as I knew it.

It took me right back to Vietnam, right back to the battlefield, right back to the wounding. And I had to work through all that stuff. It took me years of counseling and years on medication, and it’s been several years of just writing. I had to make sense of it all, and I tried to.

You speak a lot about faith in your book.

In many ways, life itself is an act of faith. The Army’s trying to spend $50 million to find out the causes of suicides. If you suffer in a war that has some meaning and purpose, you are much more able to conclude that all the suffering you went through is worth it. However, if you serve in what I call in the book misguided wars—Vietnam, Iraq—in which our leaders have not learned lessons, then it’s a hell of a lot harder to suffer and then find meaning and purpose in it.

Stepping into Darkness

Your view on faith is a bit unorthodox.

What I concluded is that for all of us, just being alive is an act of faith. Crossing a street and trusting a car is not going to run over you is an act of faith. We often interpret faith in terms of religion, but the best definition of faith I’ve ever come across was a quote in Lt. Gen. Hal Moore’s marvelous book about healing after war and after the loss of his wife: When we come to the end of all the light, we have to step into the darkness of the unknown, and we must believe that there is something solid to stand on, or else we will be taught to fly.

I have come to the end of the light and I have stepped out into the darkness of the unknown many times.

The soldier doesn’t get a chance to choose his war. War chooses him. When you’re wounded in war and you suffer, just to live another day—another hour—is in many ways an act of faith that somehow it will all come right, somehow there is meaning and purpose behind it, somehow there’s some understanding.

You write that a veteran’s poem had a great impact on your outlook.

You write that a veteran’s poem had a great impact on your outlook.

When I was head of the VA, I was going through some stuff and I came across the poem about the ups and downs of life, the sense of which is we lose so much, but then by living another day, we gain so much.

It’s hard to put into words. It has to do with survival and finding some meaning and purpose, even if that meaning and purpose is just to help other veterans. Which is one of the reasons that I had wanted to share what I went through in this book.

How hard was it to do that?

It was much more painful than I thought it would be. I wasn’t sure I could really do it. There was a time when I thought: “What the hell? Why am I going through all this crap again?”

I once heard Bill Clinton say about his book, “Living my life was tough enough, but writing about it was pure hell.” So I went through pure hell, especially in dealing with the wounds from Vietnam. And then the collapse of my life.

I’m putting this out there for basically one reason: that hopefully I will help a fellow veteran. Maybe an Iraq or Afghanistan veteran will pick up the book and see that life is worth living one more day. That’s it. Only God can speak to the heart of someone, and give them a meaning and purpose for living. But if I, through my own story, can help that happen a little bit, then the book will have been worth it.

I’m putting this out there for basically one reason: that hopefully I will help a fellow veteran. Maybe an Iraq or Afghanistan veteran will pick up the book and see that life is worth living one more day. That’s it. Only God can speak to the heart of someone, and give them a meaning and purpose for living. But if I, through my own story, can help that happen a little bit, then the book will have been worth it.

How has General Hal Moore been such a big influence on your life?

I had met him briefly many years ago, but he helped me in my 2002 campaign for my reelection to the Senate. Then we were really able to connect when a financier at a leadership retreat in Colorado said General Moore wanted me to come. I couldn’t say no to him, so I went there and came across a book about him, A General’s Spiritual Journey. I found a lot of things in there that I could relate to, and he and I have visited since then. He’s a role model for all of us.

He is part warrior, part Trappist monk. You don’t normally expect that in a three-star general, a graduate of West Point, a winner of the Distinguished Service Cross, a Korean War veteran, a Vietnam veteran.

I can relate to both sides of Hal Moore. He covers the waterfront. And Vietnam veterans have had to cover the waterfront. We’ve had to dig deeper. We’ve had to go beyond the norm. We’ve had to do things we never thought we’d do in terms of spiritual development, personal faith, physical energy and stamina. It’s called survival. We had to do what we had to do in order to survive.

Support for Our Troops

Why is it important for veterans of the latest wars to know about what happened to you and Vietnam veterans?

I just turned 67, so our generation is giving way to the succeeding generation. In terms of veterans, we’re giving way to the Iraq and Afghanistan veterans who say to me that we paved the way for them in terms of public acceptance.

I was coming in on a plane today, and the stewardess took time to thank all the active duty forces who served—there were some on board—and me publicly. That was unheard of for a couple of decades after Vietnam. I appreciate it, but I think it means more to the guys wearing the uniform today and coming back now.

People come up to me and say, “Thank you for your service.” I don’t know whether they think I was in Vietnam, Iraq or Afghanistan. But I’ll take it. It beats the hell out of the alternative, and we Vietnam veterans know the alternative, unfortunately. It’s so hard for the public to separate the war from the warrior.

People come up to me and say, “Thank you for your service.” I don’t know whether they think I was in Vietnam, Iraq or Afghanistan. But I’ll take it. It beats the hell out of the alternative, and we Vietnam veterans know the alternative, unfortunately. It’s so hard for the public to separate the war from the warrior.

How do you think the public should support our warriors?

The best way to support the troops is never to send them into war in the first place. In the second place, if they go to war, make sure it’s worthwhile. That’s the second-best way to support the troops, so then they won’t have to worry about the reception they will get upon their return.

Ross Perot told me 25 or 30 years ago: “The next time we go to war, make sure that the country is behind our forces first, then you won’t have to worry about their reception when they come home.”

I think every soldier knows that he’s taking a risk when he puts on the uniform and goes to war. I think all soldiers are to be commended because they are willing to step forward, especially now with the absence of the draft and an all-volunteer force.

Nobody expects to be blown up, or to lose their arms and legs or eyes or parts of their brain. Nobody expects to get traumatized in their mind and have to recover from that. But it sure as hell helps if the country is sensitive to what you’re facing when you come back.

Survivors Are Not Alone

How will you know if the all pain you went through to write this book was really worth it?

If one life has been saved, if one veteran decides to live another day, to give it one more shot. At times I wonder what the hell is all this about, why do I keep putting up the fight? What do I want? Why do I have to go through this stuff time and time again?

But I have not seen, and you have not heard, what the good Lord has for us. Who knows? I’m not God.

If a veteran of any war—particularly the new veterans coming back from fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan, among whom suicide is now off the charts—reads the book and if it causes him or her to understand that they’re not alone in their struggle, then my writing the book would have been worth it. But, I really didn’t enjoy going back over all of this.

I will do my normal media interviews, but it is a depressing, distressing part of American history, both the Iraq and the Vietnam wars. There’s little to brag about except somehow those of us who are living today, the survivors, sometimes have to put our arms around each other and hold on tightly in order to survive. That’s just the way it is.

This book is my arms around my fellow veterans—and my fellow countrymen who have been through this with us. We haven’t been alone. We’ve been the front of the spear, as they say. But you don’t have to go to war to feel its effects. The wives and the families have all felt the effects of Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan, and we’re feeling the effects still. So we need each other to help each other.

What do you see for yourself in the future?

I see myself finishing up my work here at the American Battle Monuments Commission to care for the 24 cemeteries where Americans have been laid to rest around the world, and in a few years retiring back in Georgia to be with my father, who’s going on 96 now. He was stationed at Pearl Harbor after the attacks.

I also see spending some time at my alma mater, Stetson University in Florida, fleshing out the Max Cleland Collection, which I’ve donated my personal political memorabilia to. And maybe cranking up some kind of Max Cleland Institute for Public Service down there, if I can ever get a little money together, teaching the next generation what it’s like, the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune of public service, and the joys of it as well.

Would you consider teaching?

No. I don’t mind appearing and talking to a class and answering questions and then leaving. The only teaching I’ve ever done was at American University in 2003. I gave all the students A’s—what the hell. I might be a great teacher, but I’d be a terrible scorer of learners.

I don’t like teaching. I like appearing. I’m like an apparition. He was here; now he’s gone. Who was that masked man?