Nearly 70 years ago, U.S. Army Master Sergeant John C. Woods carried out his most famous assignment. On October 16, 1946, the beefy 35-year-old Kansan, the only American hangman in the European Theater, dispatched 10 top Nazis sentenced to death by the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg. He boasted later that he had already executed 347 people during his 15-year career, including several American servicemen accused of murder and rape, along with Germans accused of killing downed Allied pilots and other offenses. Nuremberg was “just what I wanted,” he told Stars and Stripes. “I wanted this job so terribly that I stayed here a bit longer, though I could have gone home earlier.”

The way Woods performed “this job,” the final chapter of the Third Reich, would prove to be highly controversial—raising questions about the Allies’ decision to employ hanging as the means of execution, and Woods as the executioner.

The International Military Tribunal had sentenced 12 Nazi leaders to die—one of them in absentia. Martin Bormann, Adolf Hitler’s right-hand man by the end of the war, had escaped from his bunker in Berlin during the war’s final days and seemingly vanished. (His purported remains turned up in a Berlin construction site in 1972; in 1998, DNA tests confirmed their identity and led to the conclusion that he had died on May 2, 1945, two days after Hitler committed suicide.) That left 11 to be hanged in Nuremberg.

Hermann Göring, the highest-ranking Nazi sentenced to death, was to be first to mount the gallows, which had been hastily constructed in the Nuremberg prison gym where American security guards had played a basketball game only three days before the execution date. But Göring also eluded Woods: he bit into a cyanide pill the night before the executions began.

What particularly incensed Göring and some of the others was the planned method of execution. Corporal Harold Burson, a 25-year-old from Memphis who reported on the trial and wrote daily scripts for the Armed Forces Network, recalls: “The one thing that Göring wanted to protect above everything else was his military honor. He made the statement more than once that they could take him out and shoot him, give him a soldier’s death, and he would have no problem with that. His problem was that he thought that hanging was the worst thing they could do to a soldier.”

Fritz Sauckel, who had overseen the slave labor apparatus, shared those sentiments. “Death by hanging—that, at least, I did not deserve,” he protested. “The death part—all right—but that—that I did not deserve.”

Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel and his deputy general, Alfred Jodl, also pleaded to be spared the noose. They asked for a firing squad instead, which, in Keitel’s words, would offer them, “a death which is granted to a soldier in all armies of the world should he incur the supreme penalty.” Emmy Göring would later reportedly claim that her husband only planned to use the cyanide capsule if “his application to be shot was refused.”

That left 10 men to face the hangman. Herman Obermayer, a young Jewish GI who had worked with Woods at the end of the war providing him with basic materials such as wood and rope for scaffolds for earlier hangings, recalls that the hangman “defied all the rules, didn’t shine his shoes and didn’t get shaved.”

There was nothing accidental about the way Woods looked. “His dress was always sloppy,” Obermayer added. “His dirty pants were always unpressed, his jacket looked as though he slept in it for weeks, his M/Sgt. stripes were attached to his sleeve by a single stitch of yellow thread at each corner, and his crumpled hat was always worn at an improper angle.”

This “alcoholic, ex-bum” with “crooked yellow teeth, foul breath, and dirty neck,” as Obermayer put it, knew he could flaunt his slovenly appearance since his superiors needed his services. And no more so than at Nuremberg, where suddenly Woods was at the center of events, yet betrayed no nervousness as he carried out his assignment.

A committee of four generals—from the United States, Britain, France, and the Soviet Union—determined the overall arrangements. Workers set up three wooden scaffolds, each painted black, in the gym. The idea was to use two of the scaffolds alternately, keeping the third in reserve if anything went wrong. Each scaffold had 13 steps; the ropes—a fresh rope for each hanging—were suspended from the crossbeams supported on two posts. As Joseph Kingsbury-Smith, the pool reporter at the scene, wrote, “When the rope was sprung, the victim dropped from sight in the interior of the scaffolding. The bottom of it was boarded up with wood on three sides and shielded by a dark canvas curtain on the fourth, so that no one saw the death struggles of the men dangling with broken necks.”

At 1:11 a.m., Joachim von Ribbentrop, Hitler’s foreign minister, was the first to arrive. The original plan was for the guards to escort the prisoners from their cells with their hands unrestrained, but following Göring’s suicide, the rules changed. Ribbentrop entered the room with his hands bound; a guard then replaced the manacles with a leather strap.

After mounting the scaffold, “the former diplomatic wizard of Nazidom,” as Kingsbury-Smith archly put it, proclaimed to the assembled witnesses: “God protect Germany.” Allowed to make an additional short statement, the man who had played a critical role in launching Germany’s attacks on country after country concluded: “My last wish is that Germany realize its entity and that an understanding be reached between the East and West. I wish peace to the world.”

Woods then placed a black hood over his head, adjusted the rope, and pulled the lever that opened the trap, sending Ribbentrop to his death.

Two minutes later, Field Marshal Keitel entered the gym. Kingsbury-Smith noted that he “was the first military leader to be executed under the new concept of international law—the principle that professional soldiers cannot escape punishment for waging aggressive wars and permitting crimes against humanity with the claim they were dutifully carrying out orders of superiors.”

Keitel maintained his military bearing to the last. Looking down from the scaffold before the noose was put around his neck, he spoke loudly and clearly, betraying no signs of nervousness. “I call on God Almighty to have mercy on the German people,” he declared. “More than two million German soldiers went to their death for the Fatherland before me. I follow now my sons—all for Germany.”

With Ribbentrop and Keitel still hanging from their ropes, the proceedings paused. An American general representing the Allied Control Commission allowed the 30 or so people in the gym to smoke—and almost everyone immediately lit up.

An American and a Russian doctor, equipped with stethoscopes, ducked behind the curtains to confirm the two men’s deaths. When they emerged, Woods went up the first scaffold’s steps, pulled out a knife strapped to his side, and cut the rope. Guards carried Ribbentrop’s body, his head still covered by the black hood, on a stretcher to a corner of the gym blocked off with a black canvas curtain. This procedure would be followed for each body.

The break over, an American colonel issued the command: “Cigarettes out, please, gentlemen.”

At 1:36, it was the turn of Ernst Kaltenbrunner, the Austrian SS leader who had succeeded the assassinated Reinhard Heydrich as the chief of the Reich Security Main Office, the agency that oversaw mass murder, the concentration camps, and all manner of persecution. Yet from the scaffold Kaltenbrunner insisted—as he had to G. M. Gilbert, an American psychiatrist at the prison—that he knew nothing about the crimes he was accused of. “I have loved my German people and my Fatherland with a warm heart. I have done my duty by the laws of my people and I am sorry my people were led this time by men who were not soldiers and that crimes were committed of which I had no knowledge.”

As Woods produced the black hood, Kaltenbrunner added: “Germany, good luck.”

Alfred Rosenberg, one of the earliest members of the Nazi Party, who served as the de facto high priest of its deadly racist “cultural” creed, was the most speedily dispatched. Asked if he had any final words, he did not respond. Although Rosenberg was a self-professed atheist, a Protestant chaplain accompanied him and prayed at his side as Woods pulled the lever.

After another short break, guards ushered in Hans Frank, Hitler’s Gauleiter, or governor-general of occupied Poland. Unlike the others, after his death sentence was announced he had told Gilbert: “I deserved it and I expected it.” During his imprisonment, he had converted to Roman Catholicism. As he entered the gym,he was the only one of the 10 with a smile on his face. He betrayed his nervousness by swallowing frequently, but as Kingsbury-Smith reported, he “gave the appearance of being relieved at the prospect of atoning for his evil deeds.”

Frank’s last words seemed to confirm that: “I am thankful for the kind treatment during my captivity and I ask God to accept me with mercy.”

Next, all that Wilhelm Frick, Hitler’s minister of the interior, had to say was “Long live eternal Germany.”

At 2:12 a.m., Kingsbury-Smith noted, the “ugly, dwarfish little man,” Julius Streicher—editor and publisher of the venomous Nazi party newspaper Der Stürmer—walked to the gallows, his face visibly twitching. Asked to identify himself, he shouted: “Heil Hitler!”

Allowing for a rare reference to his emotions, Kingsbury- Smith confessed: “The shriek sent a shiver down my back.”

As a guard pushed Streicher up the final steps, he glared at the witnesses and screamed: “Purim Fest, 1946.” The reference was to the Jewish holiday that commemorates the execution of Haman, who, according to the Old Testament, was planning to kill all Jews in the Persian Empire.

Asked formally for his last words, Streicher shouted: “The Bolsheviks will hang you one day.” While Woods was placing the black hood over his head, Streicher could be heard saying “Adele, my dear wife.”

But the drama was far from over. The trapdoor opened with a bang with Streicher kicking as he went down. As the rope snapped taut, it swung wildly and the witnesses could hear him groaning. Woods came down from the platform and disappeared behind the black curtain that concealed the dying man. Abruptly the groans ceased and the rope stopped moving. Kingsbury-Smith and the other witnesses were convinced Woods had grabbed Streicher and pulled down hard, strangling him.

Had something gone wrong—or was this no accident? Lieutenant Stanley Tilles, charged with coordinating the Nuremberg hangings, later claimed Woods had deliberately placed the coils of Streicher’s noose off-center so that his neck would not be broken during his fall; instead, he would strangle. “Everyone in the chamber had watched Streicher’s performance and none of it was lost on Woods. I knew Woods hated Germans…and I watched his face become florid and his jaws clench,” he wrote, adding that Woods’s intent was clear. “I saw a small smile cross his lips as he pulled the hangman’s handle.”

The procession of the unrepentant continued—and so did the apparent mishaps. Fritz Sauckel, the man who had overseen the vast Nazi universe of slave labor, screamed defiantly: “I am dying innocent. The sentence is wrong. God protect Germany and make Germany great again. Long live Germany! God protect my family.” He, too, groaned loudly after dropping through the trapdoor.

Wearing his Wehrmacht uniform with its coat collar half turned up, Alfred Jodl only offered up the last words: “My greetings to you, my Germany.”

The last of the 10 was Arthur Seyss-Inquart, who had helped install Nazi rule in his native Austria and later presided over occupied Holland. After limping to the gallows on his clubfoot, he, like Ribbentrop, presented himself as a man of peace. “I hope that this execution is the last act of the tragedy of the Second World War and that the lesson taken from the world war will be that peace and understanding should exist between peoples,” he said. “I believe in Germany.”

At 2:45, he dropped to his death.

Woods calculated that the total time from the first to the tenth hanging was 103 minutes. “That’s quick work,” the hangman declared later.

While the bodies of the last two condemned men dangled, guards brought out an eleventh on a stretcher. An army blanket covered the body, but two large bare feet protruded from it and one arm in a blue silk pajama sleeve was hanging down on the side.

A U.S. Army colonel ordered that the blanket be removed to avoid any doubt about whose body was joining the others. Hermann Göring’s face was “still contorted with the pain of his last agonizing moments and his final gesture of defiance,” Kingsbury-Smith reported. “They covered him up quickly and this Nazi warlord, who like a character out of the Borgias, had wallowed in blood and beauty, passed behind a canvas curtain into the black pages of history.”

In his Stars and Stripes interview, Woods maintained that the operation had gone off precisely as he had planned it. “Everything went A1. I have…never been to an execution which went better,” he said. “I am only sorry that that fellow Göring escaped me; I’d have been at my best for him. No, I wasn’t nervous. I haven’t got any nerves. You can’t afford nerves in my job.”

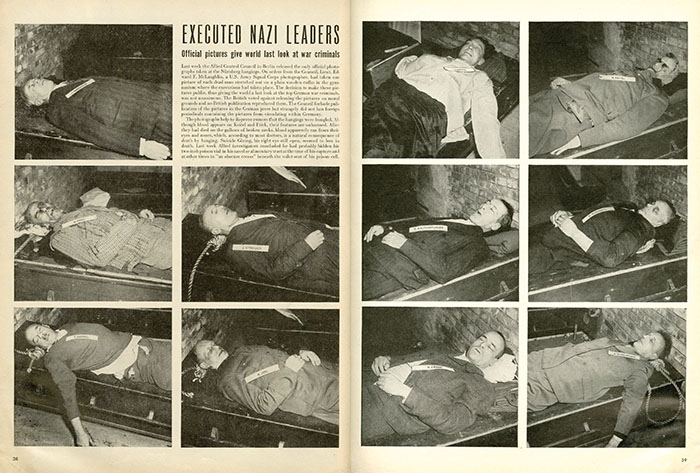

But in the aftermath of the hangings, some press accounts and military men fiercely disputed Woods’s claims. Kingsbury-Smith’s pool report left no doubt that something had gone wrong with Streicher’s execution, and probably also with Sauckel’s. A report in the London Star claimed that the drop had been too short and the condemned men were not properly tied, which meant they hit their heads as they plunged through the trapdoor and “died of slow strangulation.” In his memoirs, General Telford Taylor, who helped prepare the International Military Tribunal’s case against the top Nazis and became the chief prosecutor in the subsequent 12 Nuremberg trials, pointed out that photographs of the bodies laid out in the gym seemed to confirm such suspicions. Some of the faces appeared to be bloodied.

This prompted speculation that Woods had intentionally bungled some parts of the job. Albert Pierrepoint, Britain’s highly experienced hangman, did not want to criticize his American counterpart directly, but he did refer to newspaper reports of “indications of clumsiness…arising from the unalterable five-foot drop and the, to me, old-fashioned four-coiled cowboy knot.” In his book Nuremberg: A Nation on Trial, German historian Werner Maser asserted that Jodl took 18 minutes to die; Keitel as long as 24 minutes.

Those claims did not tally with Kingsbury-Smith’s pool report, and some subsequent accounts of the hangings may have deliberately exaggerated or sensationalized what went wrong. Still, the hangings were hardly the smooth operation that Woods insisted he had carried out. He tried to deflect criticism prompted by the photographs by saying that sometimes victims bit their tongues during hangings, which would account for the blood on their faces.

The debate about Woods’s performance only underscored the issue several of the condemned men had raised in the first place: why choose hanging over the firing squad? As Whitney Harris, a member of the U.S. prosecution team pointed out, the Allies had clearly decided to have the top Nazis share the fate of “common criminals”; they had no desire to provide them with what they considered to be the more dignified military ritual of a firing squad. Yet Woods was genuinely convinced about the virtues of his trade. Obermayer, the young GI who had assisted Woods when he carried out earlier executions, recalled “a more-or-less drunken moment” when one soldier asked the hangman whether he would like to die at the end of a rope or by some other means. “You know, I think it’s a damn good way to die; as a matter of fact, I’ll probably die that way myself.”

“Aw, for Christ’s sake, be serious, that’s nothing to kid about,” another soldier interjected.

Woods wasn’t laughing. “I’m damn serious,” he said. “It’s clean and it’s painless, and it’s traditional.” He added: “It’s traditional with hangmen to hang themselves when they get old.”

Obermayer was not persuaded. “Hanging is a special kind of humiliating experience,” he said, looking back at those encounters with Woods. “Why so humiliating? Because when you die, all your sphincters lose their elasticity. You become a shitty mess.” In his view, it was hardly surprising that the top Nazi officials at Nuremberg pleaded so desperately for the firing squad instead.

Nonetheless, Obermayer was convinced that Woods was sincere in his belief that he was carrying out a job that needed to be done with maximum efficiency and decency. Pierrepoint, his British counterpart whose father and uncle had plied the same trade, made a similar claim at the end of his career: “I operated, on behalf of the State, what I am convinced was the most humane and dignified method of meting out death to a delinquent,” he wrote in a memoir published in 1974. Among Pierrepoint’s victims during his tour in Germany were the “Beasts of Belsen,” including the former commandant of Bergen-Belsen, Josef Kramer, and the infamously sadistic guard, Irma Grese—just 22 when she went to the gallows. By the time Pierrepoint reached old age, however, his views had changed. “Capital punishment, in my view, achieved nothing except revenge,” he concluded.

Obermayer remained convinced that Woods approached all his assignments, including his most famous one, with professional detachment. It was “just another job for him,” he wrote. “I’m sure his approach to it was much more like that of the union workman who stands on the slaughtering block in a Kansas City packing house than that of the proud French fanatic who guillotined Marie Antoinette in the Place de la Concorde.”

But in the aftermath of the war, it was hardly surprising that notions of revenge and justice often intermingled, regardless of the motives of the executioners themselves.

Among his fellow GIs at Nuremberg, Corporal Burson, the Armed Forces Network scriptwriter—later co-founder of the giant global public relations firm Burson-Marsteller—regularly encountered arguments that there was no need for trials since summary executions of the top Nazis would be quicker and easier. In his scripts, Burson countered that view, quoting the reasoning of Supreme Court Justice Robert H. Jackson, the chief American prosecutor in that lead trial: “We must never forget that the record on which we judge these defendants today is the record on which history will judge us tomorrow.” Or, as Burson put it in his script: “We do not desire to employ the Nazi way…‘to take ‘em out and shoot ‘em’…for our system is not lynch law. We will dispense punishment as the evidence demands.”

As for Woods, his prediction about how he would die proved wrong. On July 21, 1950, while repairing a power line on Eniwetok in the Marshall Islands, Woods accidentally electrocuted himself.✯

Andrew Nagorski is an award-winning journalist and editor for Newsweek. He is the author of several books including The Greatest Battle: Stalin, Hitler and the Desperate Struggle for Moscow That Changed the Course of World War II and Hitlerland: American Eyewitnesses to the Nazi Rise to Power. The following is an adapted excerpt from his latest book, The Nazi Hunters, by Andrew Nagorski. Reprinted with permission of Simon and Schuster. Copyright © 2016 by Andrew Nagorski.

This excerpt was originally published in the July/August 2016 issue of World War II magazine. Subscribe here.