It was autumn 1642, and the English Civil War had broken out between the Parliamentarian Roundheads and Charles I’s Royalist Cavaliers. Expected to fight by his king’s side, attorney general and chief justice Sir John Bankes rode out of Corfe Castle in southwest Dorset. Left behind to defend the fortress were Lady Mary Bankes, their children, the maidservants and a garrison of just five soldiers.

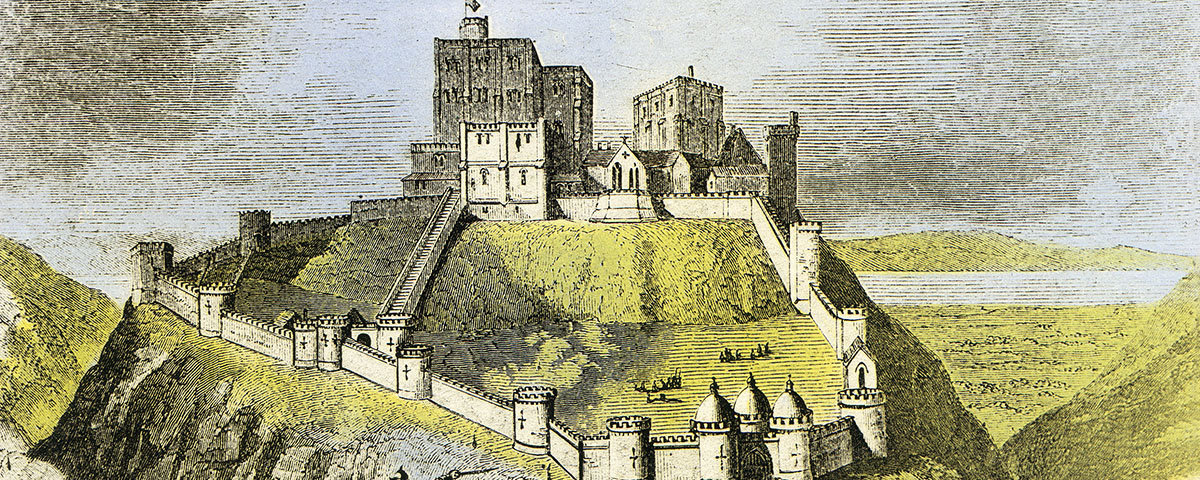

Founded by William the Conqueror in the 11th century, Corfe was an imperious place to call home. Its looming keep—among the first in Britain built of stone—commanded the sole strategic gap in the Purbeck Hills. Its capture was considered essential for control of the coastal shire.

It wasn’t long before the Roundheads came calling. In May 1643 a force of 40 sailors approached, demanding entry to the castle and the surrender of its four guns. A single cannon shot was enough to send them scurrying—and signaled that the lady of the castle was no pushover.

Within weeks the Roundheads, having secured key coastal towns, returned to besiege Corfe. Upward of 500 men led by Sir Walter Erle (one of four commissioners who would negotiate a peace with Charles in 1646) approached, Royalists caught wind of the impending attack and sent reinforcements, boosting Lady Bankes’ garrison to around 80 men. Despite his advantage in numbers, Erle found the castle a disheartening target. An attacking force had to overcome three uphill lines of thick walls, gatehouses and portcullises, all the while within firing range of the keep. The garrison readily repulsed the first assault waves. According to the 1643 journal Mercurius Rusticus, a desperate Erle offered a £20 bounty to the first of his men to scale the walls. When that proved insufficient motivation, he proffered booze, apparently in the belief “drunkenness makes some men fight like lions that being sober would run like hares.” During the spirit-fueled pincer attack that followed, Lady Mary, her garrison and staff rained down stones and hot embers from the battlements. After six fruitless weeks Erle—with the loss of 100 men to Bankes’ two, and on learning Royalist forces were en route to lift the siege—withdrew in haste. Sir John even returned home for a brief leave.

With Lady Bankes’ stalwart defense of Erle’s onslaught, Corfe represented the last Royalist stronghold between London and the southwest city of Exeter. “Brave Dame Mary” was gaining a reputation. But in December 1644 her luck began to change—word came her husband had suddenly fallen ill and died. She remained holed up amid hostile neighbors.

In June 1645 Parliamentarians under Sir Thomas Fairfax and Oliver Cromwell scored a decisive victory at Naseby, breaking the back of the Royalist army. Months later Corfe again found the enemy at its gates, this time led by Col. John Bingham, governor of Poole. Despite weeks of resistance and an attempt by a daring young Royalist to spirit away the redoubtable Lady Bankes (who refused to leave), the castle ultimately fell.

The weakness was human, but the fault wasn’t Lady Mary’s. A turncoat officer in her garrison had opened a sally port to a party of enemy musketeers disguised as Royalist Cavaliers. In recognition of Lady Bankes’ resolve, the Parliamentarians allowed her to keep the keys to the fortress. Later that year the Roundheads rent asunder indomitable Corfe with gunpowder, leaving it in ruins.

When Lady Bankes died in 1661, St. Martin’s Church [stmartins-ruislip.org] in Ruislip, Greater London, where she is interred, erected a plaque commending the deceased for “a constancy and courage above her sex.” That said, more recent historians have called into question accounts of Lady Mary’s heroic defense, as other period records suggest she and her daughters may have left for London ahead of the final siege.

But Corfe Castle [corfe-castle.co.uk] remains constant, its jagged ruins still commanding the gap in the Purbeck Hills. Owned by the National Trust conservation organization, the site is open year-round to visitors, whom guides regale with the story of Brave Dame Mary and a number of other historical tidbits, including the 978 murder of Anglo-Saxon boy King Edward the Martyr.