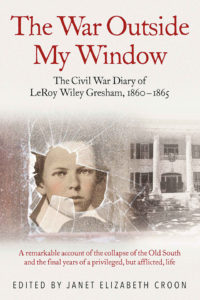

Edited by Janey Elizabeth Croon

Savas Beatie, 2018, 441 pages, $34.95

In 1860, 12-year-old LeRoy Gresham began keeping a daily diary. The second son and middle of three children, he had been horribly crippled four years earlier when a chimney collapsed on his left leg. Unable to walk unaided, he was further beset by what medical experts now believe was tuberculosis, which produced painful abscesses along his spine that often interrupted his sleep and forced him to lie down much of the time.

Gresham’s family had the means to provide the best medical care—which proved largely ineffectual—and slaves who could help care for him and occasionally pull him about the city in a specially rigged wagon. Essentially an invalid, he was rarely able to go to church and never fit to accompany his father on trips to the family’s two plantations south of Macon, Ga.

Gresham’s family had the means to provide the best medical care—which proved largely ineffectual—and slaves who could help care for him and occasionally pull him about the city in a specially rigged wagon. Essentially an invalid, he was rarely able to go to church and never fit to accompany his father on trips to the family’s two plantations south of Macon, Ga.

Despite almost constant pain, Gresham proved a faithful and observant chronicler of life in the South immediately before and during the Civil War. From his home in Macon, he produced a detailed account of his daily activities, interlaced with reports, both rumored and real, of the shifting fortunes of Confederate forces. His entries betray the indiscriminate eye of an adolescent boy: news of battles and complaints about Southern generals often share equal space with reports about the quality of the fruit he ate that day, the antics of his dogs, the books he read voraciously, and the often very unpleasant weather.

Gresham laments the death of the “Brave, gallant Stonewall Jackson…the pride of the nation…[who] never committed an error” and a few sentences later complains, “I never in my life saw peaches so defective wormy + rotten everywhere.” After the fall of Vicksburg. General James Pemberton is “as grand a sneak as lives,” while throughout Robert E. Lee remains above criticism.

Gresham relied on word-of-mouth accounts, the telegraph, and newspapers for information that often proved suspect. He hopes for European intervention long past the point when that proved impossible. In an April 8, 1862, entry, the Battle of Corinth (Shiloh) is a “Great, and Glorious Victory!; nine days later he reports “the second day was drawn.”

What Gresham fails to mention or understates is telling. Despite several references to the Union army as “abolitionists,” the Emancipation Proclamation goes unremarked upon until a February 1863 entry claiming, “Lincoln is going to raise an army of 150,000 contrabands.” He takes for granted the ministrations of the family’s slaves and seems untouched by one’s failed attempt to run away. Without being specific, he hints that a rash of fires that destroyed homes and businesses suggest that Macon’s enslaved population was increasingly restive as the war progressed.

Throughout the diary, superbly edited and annotated by Janet E. Croon, a retired public-school teacher from Northern Virginia, Gresham undramatically speaks of his constant pain. Croon argues convincingly that Gresham did not know he was dying until the day before his death on June 18, 1865, when he asked his mother directly, “I am dying, ain’t I?” The final entry in his diary, written nine days earlier, reads only, “I am perhaps….” LeRoy Gresham’s gritty diary demonstrates that bravery was not the sole province of fighting men during the Civil War.