Tom Collins will never forget Jan. 19, 1968. The Army military police officer was standing guard onboard a cargo ship in the middle of Qui Nhon harbor in central South Vietnam. His watch was nearly over, and he was waiting to be relieved. Collins stood by the railing and checked out an approaching boat to make sure it wasn’t an enemy craft. He saw that it was an American water taxi and comrades from the 127th Military Police Company were clustered onboard.

Then something unusual caught Collins’ eye. On the boat, amid all the olive drab uniforms and dark green helmets marked “MP,” stood a civilian dressed in a madras shirt and white jeans. He had red hair that looked familiar. “Chickie?” Collins thought, and shook his head in disbelief. It couldn’t be his friend from the old neighborhood back in the States. Could it?

As the water taxi pulled alongside the cargo ship, the MP heard the civilian call out, “Hey, Collins!” It was Chickie!

A dumbfounded Collins answered: “What the hell are you doing here?”

Chickie pulled a can from his backpack and handed it to his friend. “I came to give you a beer,” he said. “This is from the Colonel and me and all the guys in Doc Fiddler’s.”

Collins popped open the still-cold Pabst Blue Ribbon beer and guzzled it down, wondering how John “Chickie” Donohue made it to the war zone in Vietnam, thousands of miles from that little bar in the Inwood neighborhood of Manhattan, New York.

“I was shocked,” Collins recalled in an interview. “I couldn’t believe he would go in harm’s way just to bring me a beer.”

Donohue also delivered beer to three other friends in Vietnam.

The improbable but true story of his odyssey is recorded in The Greatest Beer Run Ever: A Memoir of Friendship, Loyalty and War, by Donohue and Joanna Molloy, a former New York newspaper reporter and columnist. The book is being made into a movie by producer and director Peter Farrelly, who scored three Academy Awards for Green Book in 2019. Initial media reports put Zac Efron, Russell Crowe and possibly Bill Murray in starring roles.

Donohue’s journey halfway around the world began on a cold night in November 1967 when he strolled into Doc Fiddler’s seeking brew and brotherhood. Then 26, the former Marine was in between jobs as a seaman on merchant ships. The mood was low in the bar. News filtered in about how badly things were going in Vietnam and how protesters were taking it out on the military men who had served there.

The Greatest Beer Run Ever

by John Donohue and JT Molloy

If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.

“We got to do something for them,” growled bartender George Lynch, nicknamed “the Colonel.” He had made it only to private first class, but patrons of the bar promoted him out of respect for his deep patriotism. “Somebody ought to go over to ’Nam, track down our boys from the neighborhood and bring them each a beer,” the Colonel proclaimed. “We gotta support them!”

After more than a few beers, everyone in the bar was in raucous agreement with the Colonel—including Donohue, who said he would go. “Get me a list of the guys and what units they’re with, and I’ll do it,” he heard himself saying.

The next thing he knew, Donohue was headed to Vietnam with a burlap sack full of American beer and a list of six buddies from Inwood. To carry out his unauthorized mission, he used his seaman’s card to get a spot on the merchant ship hauling ammo. Donohue had no idea what he was going to do once he got to Vietnam.

“There was no plan,” he remembered. “There was nothing material to plan with! I just kept going. How could you plan to get on a couple of planes and helicopters and find these guys? It’s not plannable!”

Donohue left New York on the merchant ship in late November 1967 and got to Vietnam on Jan. 19, 1968. He hitched rides on jeeps, trucks, aircraft and water taxis to search for his pals. All he had to do was find six guys from Inwood, New York, in a haystack of some 500,000 American service members.

Donohue’s quest was complicated by bad timing. He stumbled into the communists’ Tet Offensive, launched on Jan. 31, 1968, when the North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong struck bases and cities throughout South Vietnam, inflicting thousands of casualties.

His unlikely success amid all of those hurdles sounds like a tall tale concocted after drinking too many beers—or perhaps the story of a miracle bestowed by a heavenly hand.

“Do I think God sent me there? No,” Donohue, now 79, said in a thick New York City accent. “I think George Lynch sent me. But, if there was any divine intervention, he did it in my favor.”

Almost immediately after the ammo ship docked at Qui Nhon, Donohue grabbed the burlap sack of cold beer from the vessel’s refrigerator and jumped on a water taxi ferrying troops around Qui Nhon harbor. Immediately, he noticed the soldiers on the boat had the same insignia as Collin’s unit: 127th MP. On a lark, Donohue asked if anyone knew his friend, who had a fairly common name.

“Yeah, we know Collins,” one of them said. “He’s on that ship right over there.”

Donohue couldn’t believe his luck. He walked up the cargo ship’s gangway to his stunned friend, who asked what was going on. “I came over to buy you a beer,” Donohue recalled saying. “The Colonel sends his regards. Oh, and your mother says you better write to her so she knows you’re OK.”

After Collins downed the beer, he brought Donohue to his barracks, where the latter explained his mission. Next on the list was Rick Duggan, who was somewhere up north with the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile), near An Khe in South Vietnam’s Central Highlands.

“How the hell are you going to get up there?” Collins asked.

Earlier in the day, Donohue had spoken with a pilot scheduled to go to An Khe on a mail run the next day. He hitched a ride on the pilot’s Grumman HU-16 Albatross plane and landed at the base, only to find that the 1st Cav had moved to a remote location closer to the Demilitarized Zone border between North and South Vietnam.

Donohue found out where the unit had gone, then hitched a ride in a jeep headed in that direction. He hopped in the back with two soldiers and began speaking to the driver, who asked his unexpected passenger what he was up to. Donohue explained.

Suddenly, the jeep screeched to a halt. The driver turned around. “Holy Christ, Chick! What the hell are you doing here?”

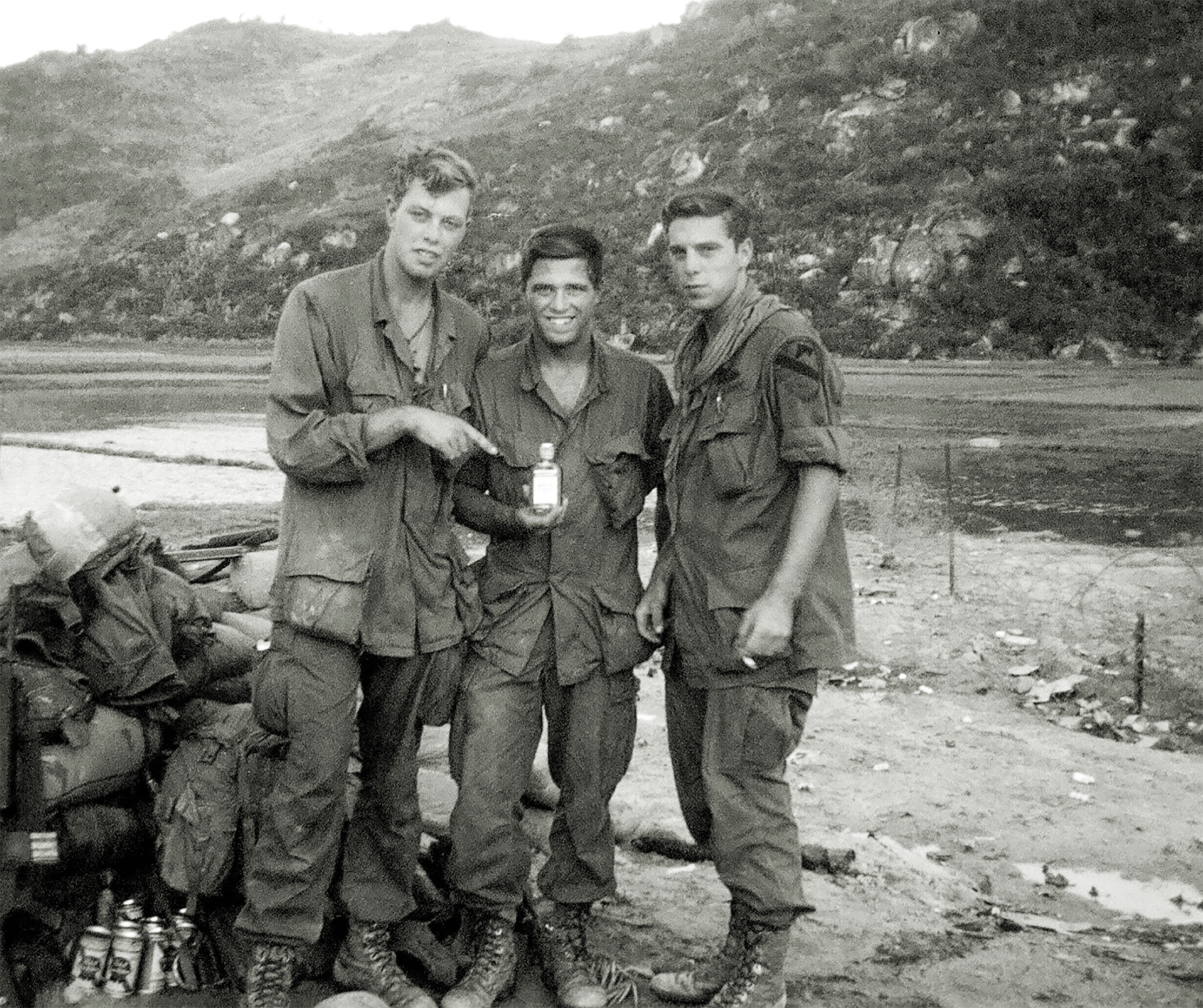

Donohue was now looking at Kevin McLoone, another friend from the neighborhood on the list. The two Inwood drinking buddies had a short reunion and toasted each other with beer before McLoone, a Marine in the transport helicopter squadron HMM-261 “Raging Bulls,” took Donohue to the An Khe airfield.

At the airstrip, Donohue jumped on a two-engine prop plane and asked if anyone knew how he could find Bravo Company of the 1st Battalion, 5th Cavalry Regiment.

Two young soldiers piped up that they were with that unit. Donohue asked if they knew Duggan. They said they did. After the plane landed at Phu Bai, about 10 miles south of Hue, Donohue tagged along as the troopers marched on their own mission.

The beer delivery man soon learned that Bravo Company was at Landing Zone Jane, near Quang Tri city, about 30 miles north of Hue. Donohue managed to wrangle another ride on a flight, this time a Huey helicopter The major in charge of flight operations at LZ Jane asked very few questions.

Donohue, who served in the Philippines and Japan when he was in the Corps from 1958 to 1964, was surprised to see the deference received by a civilian without papers in a war zone. He soon realized that most officers thought he was someone else.

“They didn’t know how to treat me,” Donohue said. “They just assumed I was some sort of government agent for the CIA or another group. That’s how I was able to talk my way onto so many planes.”

Donohue eventually made it to LZ Jane. He found out that Duggan was just beyond the perimeter at an ambush post. When the two men met, Donohue got the typical greeting from one of his neighborhood friends: “Chickie! What are you doing here?”

Duggan took Donohue to his post. They had to wait on the beer toast because the enemy was so close. Duggan handed a poncho to his friend, who was wearing the same clothes as the day he arrived in Vietnam.

“That outfit is like wearing a sign that says, ‘Shoot me, I’m from New York,’” Duggan told him.

In the middle of the night, they were awakened by sounds in the dark. It was the North Vietnamese Army. The Americans sent up flares, and a firefight started. Donohue was handed an M79 grenade launcher and told to take cover, which he did, deep in a hootch.

Eventually, the shooting quieted down, and the two men made their way back to LZ Jane, where they were finally able to toast their friendship. Duggan’s unit was ordered to a new position in the A Shau Valley, so Donohue left on another chopper.

By some remarkable stroke of luck, the Inwood native had tracked down three buddies in Vietnam in four days, bunking down with them in barracks, tents and outposts. Donohue set out for Saigon. He had missed the return voyage of the merchant ship, so now he was stuck in Vietnam with no papers—and no way out. It took some time, but Donohue got a passport and visa through the U.S. Consulate. He arranged a flight to Manila in the Philippines so he could book passage on another freighter returning to the States.

While waiting, he walked into a bar and—in another roll of the dice that turned up a “Lucky 7”—spotted a merchant mariner from New Jersey. He had previously sailed with the man, who helped Donohue get fresh clothes and food from his ship.

As they walked through South Vietnam’s capital, Donohue’s friend pointed to a tiny sliver of the moon and noted that it was New Year’s Eve on the Vietnamese calendar. “They call it Tet,” his buddy said. “They’ve called a truce! It’s party time, man!” They didn’t stay out too late, though. Donohue had an early flight to catch the next morning—Jan. 31, the dawn of the Lunar New Year.

Shortly after midnight, a massive attack by the NVA and Viet Cong engulfed the country. The launch of the offensive during a truce caught American and South Vietnamese troops off guard. Saigon was one of the many places under attack.

Donohue, on his way back to the hotel, at first thought the explosions were fireworks displays to mark the start of the Tet holiday. However, it soon became apparent that this was no celebration.

“There was firing everywhere,” Donohue recalled. “There were bodies lying in the street in front of the American Embassy. I hid behind a tree for safety.”

The Viet Cong blew a hole in the wall around the U.S. Embassy but were immediately confronted by Army MPs and Marines. The enemy never got into the building itself. After several hours of fighting inside the compound, the MPs and Marines eliminated the VC threat, killing 18 of the 19 intruders. Four MPs and a Marine also died.

Just before the Tet Offensive started, Donohue had managed to track down a fourth friend on his list. Bobby Pappas, a communications specialist in the Army, was stationed near Saigon at Long Binh, the largest ammunition supply depot in the world.

Donahue hitched a ride to the massive base. He told MPs at the gate his crazy story about buying beers for his buddies in Vietnam. They laughed and escorted him directly to Pappas, who was in a bunker. Donohue greeted him with, “Hey, buddy!”

Pappas looked at him and said, “Chick? What the hell are you doing here?” Donohue handed him one of the last beers in his bag. They talked about Vietnam, and Donohue said he thought the war was about over.

When Tet erupted, Donohue became concerned about his friend. On the morning of Jan. 31, while dodging bullets and hiding behind trees, Donohue saw a huge mushroom cloud in the sky to the northeast of Saigon.

He knew it could only mean one thing: Viet Cong commandos had attacked the ammo dump and blew it up. He feared for Pappas’ life and headed back to Long Binh.

“There were shells all over,” Donohue remembered. “The place was a wreck. I went into the bunker and Bobby was standing there. He looked at me and said, ‘You? You told me this freaking war was over!’ He was so mad at me. I looked at him and said, ‘Thank God!’ I thought he was dead.”

There were still two names on his list to toast with beer. Although he didn’t know it at the time, one of them, Marine Richard Reynolds, had been killed in combat on Jan. 20 in Quang Tri province. Another friend, Joe McFadden, had been shipped home by the Army with a bad case of malaria.

That was the end of Donohue’s beer-delivery mission. Now he had to get back home. As usual, he had no plan. Given that fierce fighting was still raging around Vietnam, U.S. government officials had more pressing concerns than helping him get out of there. Fate, once again, played a hand. Donohue learned that a merchant ship had been attacked in the Saigon River. An oiler in the engine room had been injured and couldn’t make the return trip. Donohue’s job in the merchant marine? Oiler. He signed on.

“I knew the union rules,” Donohue said. “A ship can’t sail short of a full crew if there is a qualified seaman in port. I convinced the captain he had to hire me.”

Donohue sailed to the West Coast, flew to New York City and took a taxi to Doc Fiddler’s on April 1, 1968.

“I got out of the cab—I will never forget that—and was paying the driver when someone walked out,” he recalled. “He yells back in the door, ‘Hey! It’s Chickie! He’s back alive!’ By that time, some of the guys I met in Vietnam were back in the old neighborhood. They knew I was there but didn’t know what had happened to me.”

The Colonel was overjoyed. He poured himself and everyone in the bar a brew and gave a toast: “To Chickie, who brought our boys beer, respect, pride—and love, goddamn it!”

Life slowly returned to normal in Inwood. All the men who received American beer in Vietnam returned home. They went on with their lives, got jobs and raised families. Donohue purchased Doc Fiddler’s in 1970 and ran the bar for several years.

Not much was said about what happened, mainly because the veterans didn’t want to dredge up painful wartime experiences. Donohue, Collins, McLoone, Duggan and Pappas met from time to time but little was said about what took place in Vietnam in January 1968. The shared experience created a mutual bond, nonetheless.

The men did start talking about that crazy adventure after Molloy proposed writing a book, and documentarian Andrew Muscato made a short film entitled The Greatest Beer Run Ever for Pabst in 2015. They even gathered in 2019 to mark the occasion during the 50th anniversary commemoration of the war. Now the five friends talk regularly with each other about what happened and how it shaped their lives.

Today, Donohue shakes his head when he thinks about how the journey of a lifetime all fell together so incredibly. He realized at the time—and still acknowledges today—it was something he just had to do.

“I was often asked, ‘Why did you do that?’” he said. “Simply put, it was the right thing to do. As outrageous as the idea sounded coming from the Colonel and as difficult as it would have been to accomplish, it was just the right thing to do—or at least try to do it. So I did it.”

And when he did it, the guys from the neighborhood were very impressed. As McLoone said just before guzzling his PBR in Vietnam, “Wow! That’s a helluva beer run!” V

David Kindy is freelance feature writer who lives in Plymouth, Massachusetts. He is a frequent contributor to magazines that cover military history.