Frank Meyer combed Asia for unknown fruits and crops that proved valuable to U.S. agriculture

“… the song of liberty is so sweet. Now in these last days the sun shines brighter, the birds sing more gaily and everything seems more laughing, now that my prison walls are crumbling away under the steady hammer strokes of father time,” Frank Meyer wrote shortly before leaving a job at a nursery in Washington, DC, to scout plants in the wild, a task the young man loved even more than tending specimens in a greenhouse. Born Frans Nicholas Meijer in Holland in 1875, Meyer spent more than a decade roaming China and Central Asia on behalf of David Fairchild, himself a legendary plant explorer risen to chief of the U.S. Agriculture Department. From the field Meyer sent to USDA tons of plant material for study and experimentation. Many Meyer specimens led to valuable crops, including a soybean now among the varieties most planted in the country. Meyer achieved immortality for discovering in China a dwarf citrus tree with unusually sweet fruit that he introduced to America, where it is known as the Meyer lemon. Smaller, rounder, and thinner-skinned than standard lemons, the Meyer descends from the interbreeding of the citron, the pomelo, and the mandarin orange.

A son of a modest family, Meyer managed to apprentice himself at 14 to the great Dutch botanist Hugo de Vries, who besides training his worker taught him French and English. Within eight years Meyer was head experimental gardener at Amsterdam’s botanical garden, the Hortus Botanicus. In 1901, he sailed to America, worked a year in greenhouses in DC, then for four years traveled in the United States, Cuba, and Mexico.

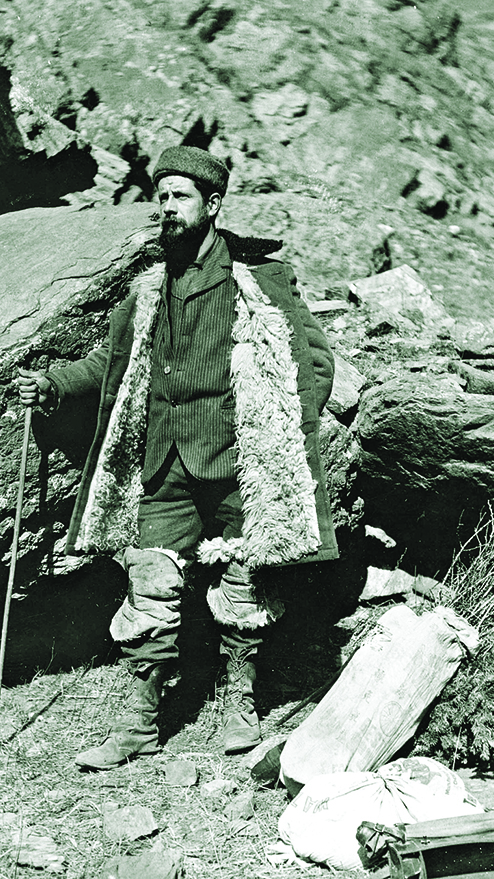

The assignment Fairchild proffered was not for the fainthearted; the holder would be traveling alone, with only enough money to hire a translator and buy basic supplies. Meyer eagerly signed on. As a precaution, he cultivated a rough air, letting his hair grow and wearing a sheepskin coat and heavy boots. As part of a wave of plant-collecting adventurers dispatched to gather novel and economically useful specimens, he endured the occasional wilderness mugging.

In three expeditions that collectively consumed 13 years, Meyer meandered nation to nation, trudging the wilds to find and collect seeds, fruits, and cuttings that he carefully packed for shipment to the States. In China, he located the source of a fungal blight destroying American chestnut trees.

Witnessing myriad uses of the soybean, Meyer recognized that legume’s commercial potential. North Americans had been growing soybeans since colonial days, but Meyer collected 42 more varieties, including the first found to be a source of oil. In 2018 soybean acreage surpassed corn as top crop in the United States. He collected countless novel varieties, including types of bamboo, pear, persimmon, and plum. In Afghanistan, he spied a tiny wild fruit that proved to be the progenitor of the domesticated peach.

Meyer kept Fairchild abreast of his doings with lively updates by mail. “I am sitting now in a Chinese house, for the inn I lived in at first was too noisy and dark and there was no room to dry seeds or specimens,” he wrote while holed up as warlords battled in 1917. “Some mice are running about, mosquitoes buzz, a cricket sings in an old wall and the policeman, who I stationed to spy upon me, snores on a bench, for it is well into the night. Tomorrow we may go to see a lot of wild pear trees, 15 miles away from here….”

Reproved for departing a locale before its vegetation leafed out, Meyer wrote that he was not able to remain still for long, “unless I was of a barnacle nature, which God help me, I never hope to become.” He and an assistant once hiked 40 miles in 15 hours to catch a train. Some of Meyer’s lodgings were so cold the ink in his pen froze.

By 1917, Meyer wanted to return to the United States. He confessed to his patron that he worried about how he could make a living. “I might easily advise you to come back to this country and take up the breeding of plants, but I do not feel sure that a man of your restless disposition will be contented with the necessarily quiet life of a plant breeder,” Fairchild replied.

Meyer admitted to his boss in a letter from Hupeh, in central China, that fieldwork was wearing. “Of course, this exploration work with its continuous absence from people who can inspire one, gets pretty hard on one’s nerves,” he wrote. “One must be some sort of a reservoir that carries along all kinds of stores. Soldiers in the field have more dangers to face, but they get at least companionship and often recreation supplied to them. For about one month now I haven’t seen a white person, for all of the missionaries are at the mountain and seaside-resorts and travelers one rarely meets here…”

On June 1, 1918, Meyer’s reservoir ran dry. At 11:30 p.m. fellow passengers on a Yangtze riverboat bound for Shanghai reported him missing from his cabin. Days later his badly decomposed body, bearing no trace of violence, surfaced 30 miles downriver.

His servant recalled that Meyer had described a dream in which his father and old friends came to see him, a vision Meyer considered a bad omen. The American consul reported on June 14, 1918, “It appears that Mr. Meyer while traveling down the Yangtze from Hankow to Shanghai on the S.S. `Feng Yang Maru’ of the Nisshin Kisen Kaisha, was drowned near Wuhu. Whether he fell off the ship accidentally or committed suicide in a fit of depression will probably never be known.”

Meyer specified in his will that $1,000 be distributed among colleagues or spent on an outing or entertainment. In 1920 Fairchild established the USDA Frank N. Meyer Award honoring distinctive service to the National Germplasm Program in the memory of an intrepid scientist who braved remote regions and survived cold, civil war, and illness only to encounter his most dangerous foe within.

“The remarkable new field that he has opened up, the vast quantities of material that he has introduced, will always remain as a great epoch in American agriculture and horticulture,” a friend wrote. “I know that few people ever realized the tremendous battle that was raging within his soul…”

This story appeared in the December 2019 issue of American History.