On April 1, 1915, Roland Garros took off in a Morane-Saulnier L from an airfield in northern France, planning to play an April Fool’s Day trick on the Germans. The Frenchman soon spotted a two-seater Albatros B.II reconnaissance plane and approached it head-on—no doubt much to the German pilot’s surprise. The Morane-Saulnier challenging him was a single-seater, without an observer in the rear armed with a rifle, as was the German observer. Perhaps the Albatros pilot never even saw the gas-operated Hotchkiss machine gun fitted in front of Garros before the Frenchman opened fire. As the bullets passed through Morane-Saulnier’s propeller arc and into the Albatros, the German pilot slumped dead over the controls and the aircraft dropped out of the sky, the observer helpless in the rear cockpit. On that day, as American World War I pilot Arch Whitehouse later wrote: “Roland Garros had given the machine gun wings. His fantastic device gave birth to a new and most deadly weapon, providing the military forces with a lethal piece of armament. It made the airplane as important a war machine as the naval dreadnought.”

Garros was 26 when he became the first pilot to down an enemy airplane with a machine gun firing through the propeller. Described by a contemporary as possessing “a liquid eye and an olive skin,” the young Frenchman had gained his pilot’s licence in 1910 and that year competed in Britain, France and the United States flying a Demoiselle, a bamboo-and-fabric monoplane that aroused much hilarity at exhibitions. The British aviation journal Aero reported that “the whole attitude and jerky action of the machine suggest a grasshopper in a furious rage.”

Garros soon graduated to the Morane-Saulnier H, a monoplane designed by Raymond Saulnier and the Morane brothers, Léon and Robert. In September 1913, he flew it across the Mediterranean Sea from France to Tunisia in what The New York Times described as “one of the most notable feats in aviation.” Garros returned to Europe a hero, but already his aerial fame was being overtaken by events.

Earlier in 1913, the First Balkan War had ended with a resounding victory over the Ottoman Empire for the combined forces of Serbia, Greece, Montenegro and Bulgaria. During the conflict Bulgaria used aircraft to conduct reconnaissance missions over enemy lines, also dropping two bombs—by hand—on Odrin, Turkey. Aircraft designers were now awakened to the airplane’s military potential, and the race was on to create a plane capable of more than just scouting. The real challenge was armaments, which would exercise the ingenuity of both Raymond Saulnier and Swiss engineer Franz Schneider in 1913.

Schneider had worked for the French manufacturer Nieuport before joining the German Luft-Verkehrs Gesellschaft (LVG) firm. In July 1913, he patented an “interrupter” gear, so named because when the pilot pressed the gun trigger a series of mechanical linkages interrupted firing until the propeller blade was clear. But the German military was unimpressed with Schneider’s work, refusing even to loan him a machine gun for testing.

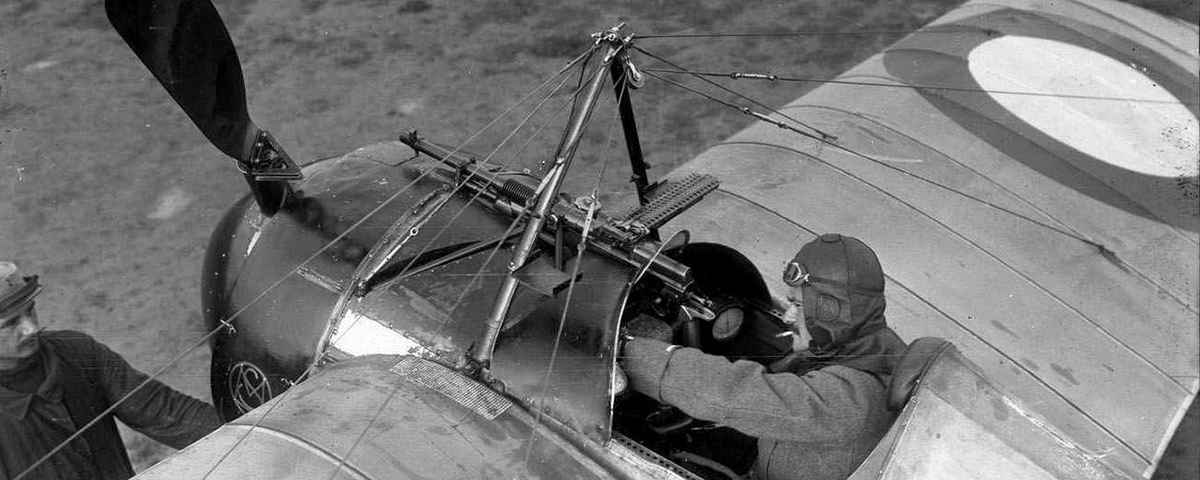

The Germans might have been more receptive had they known that Saulnier was conducting similar experiments in France. He was in fact wrestling with the same problem confronting Schneider: The structural design of front-engine aircraft restricted the use of machine guns to a three-quarter rear field of fire by an observer sitting behind the pilot. Saulnier knew the solution lay in inventing a device that allowed the pilot to operate a forward-firing machine gun. He balked at experimenting on an interrupter gear because with open-bolt machine guns such as the Hotchkiss and Lewis, the ammunition had no “uniform period of ignition.” This unpredictability could lead to hang-fire failures (an unexpected delay between a weapon being triggered and the bullet actually firing) and the possibility of a bullet hitting the propeller. Instead Saulnier fixed wedge-shaped steel deflector plates to the propeller blades where the arc crossed the line of fire of a front-facing gun. The French military loaned him a Hotchkiss machine gun, and initial trials went well, with only superficial damage to the prop. But ultimately Saulnier’s invention also met with disdain. The French, like the Germans, still believed aircraft didn’t require heavy armament. When World War I began in July 1914, neither country was equipped for an offensive aerial war.

Nor were the British. Fighter ace James McCudden, who would have 57 victories at the time of his death on July 9, 1918, began the war as a mechanic with No. 3 Squadron. In his memoirs, completed shortly before he was killed in a flying accident, McCudden described the arrival at his squadron of two Bristol Scouts: “These Scouts were far ahead in performance of anything the Germans had in the air at this time, but the trouble was that no one had accurately foreseen developments as regards fitting machine-guns so that they could be used with any effect from single-seater machines. The Bristol in No. 3 Squadron was fitted with two rifles, one on each side of the fuselage, shooting at an angle of about 45 degrees in order to miss the air-screw.”

In December 1914, Garros paid a visit to his old friend Saulnier and asked him to fit metal deflector plates to the propeller blades of his Morane so that he could mount a Hotchkiss gun at the front of his cockpit. Garros then spent the first few weeks of 1915 familiarizing himself with his new weapon. But he soon discovered there was a downside to Saulnier’s invention, as described by McCudden after No. 3 Squadron took delivery of a Morane-Saulnier Nm with a front-mounted Lewis gun. “[It] had a piece of steel fixed on each blade directly in front of the muzzle of the Lewis gun,” wrote McCudden. “So that the occasional bullets that hit the propeller were turned off by these hard-steel deflectors—as they were called. The deflectors took off almost thirty percent of the efficiency of the propeller, so that for the smallness of the machine and its ample power (80-hp Le Rhône) it was not very efficient in climb and speed.”

By the end of March 1915, however, Garros had gained sufficient confidence in the deflector plates to test them in an operational flight, so he embarked on the April 1 patrol that ended in his victory over the Albatros B.II. The shoot-down made the front page of the Salt Lake Tribune on April 10, when the paper carried an eyewitness account of the encounter from Major Raoul Pontus: “Presently the crackling of a quick-firer showed the Frenchman judged himself sufficiently near to take the offensive. Could the German escape? It seemed difficult, for Garros shot forward in great bounds, getting nearer and nearer, but the German observer used his carbine freely and it seemed that a bullet might strike the Frenchman. Suddenly a long jet of white smoke gushed from the German machine and then a little flame, which, in an instant, enveloped the whole aeroplane. Notwithstanding the extreme peril the pilot took to flight but his effort to escape soon was converted into a horrifying downward plunge.”

The day after the Tribune’s report, Garros attacked another two-seater, an Aviatik B.I, whose observer emptied his Mauser pistol at Garros. The Frenchman claimed a victory, but could not get it confirmed. The next day he claimed another unconfirmed success over an LVG Scout, and on April 15 he dispatched another Aviatik. Garros’ lethal stretch continued on the 18th, when he shot down an Albatros as his third confirmed victim—earning him a citation for the Legion of Honor and an invitation to address the Directorate of Military Aeronautics.

Suddenly the French authorities were desperate to learn more about Saulnier’s invention. With the benefit of hindsight, one might expect they would have done their best to ensure their new secret weapon didn’t fall into enemy hands. But perhaps their belief in Garros’ invincibility explains why they allowed him to take off alone on April 18 for yet another patrol.

Accounts vary as to what exactly happened as Garros approached the Belgian town of Courtrai, four miles from the French border. According to the leader of a detachment of German soldiers guarding the railway line, Garros attacked a southbound train approaching on the line between Ingelmunster and Kortrijk.“Suddenly the plane went into a steep dive of about 60 degrees from a height of about 2,000 meters to about 40 meters from the ground,” wrote the German. “As the plane had swooped down over the train the Bahnschutzwache troops had fired on it following my order to open fire. We shot at him from a distance of only 100 meters as he flew past. After he had thrown his bomb at the train he tried to escape, switching his engine on again and climbing to about 700 meters through the shots fired by our troops. But suddenly the plane began to sway about in the sky, the engine fell silent, and the pilot began to glide the plane down in the direction of Hulste [northeast of Courtrai].”

Other reports made no mention of a train, attributing Garros’ problems to engine failure as he was strafing German troops in the trenches. Either way, the Frenchman managed to nurse his Morane-Saulnier away from Courtrai before eventually landing in a field. He leapt out of the plane and tried to destroy it, but the wing fabric and spruce framework were damp and wouldn’t catch fire. Then the pilot spotted an approaching enemy patrol and fled, evading his pursuers but leaving his precious machine in German hands.

Garros was soon captured by Württemberger cavalrymen, one of whom told the Schwabishen Merkur newspaper that their prisoner “was a good-looking, dark-haired Frenchman with a high white forehead, a slightly crooked nose and a small black beard. With his lips pressed together he looked at us in wide-eyed amazement.” The capture of the most famous flier of the war made headlines around the world. The French paper Le Temps described how “the news has caused a great emotion in France…because his exploits have made him the terror of the Germans.”

When members of the German army air service inspected the Morane-Saulnier, they couldn’t believe their luck. Within days Garros’ airscrew had been transported to the workshop of Dutch aviation engineer Anthony Fokker.

Fokker had learned to fly at age 20, and just two years later, in 1912, he started building airplanes. At first business was slow, but then came war. As Fokker wrote in his memoirs: “In the desperate struggle to keep the business afloat I had joyfully sold my planes to the German army…Holland had preferred French aeroplanes; England and Italy hardly responded to my offers; in Russia I was put down by the general corruption, and only Germany seemed to give me a civil reception, albeit not with open arms. As a young man of twenty-four, I wasn’t very interested in German politics and cared not where it would lead. I was Dutch and neutral.”

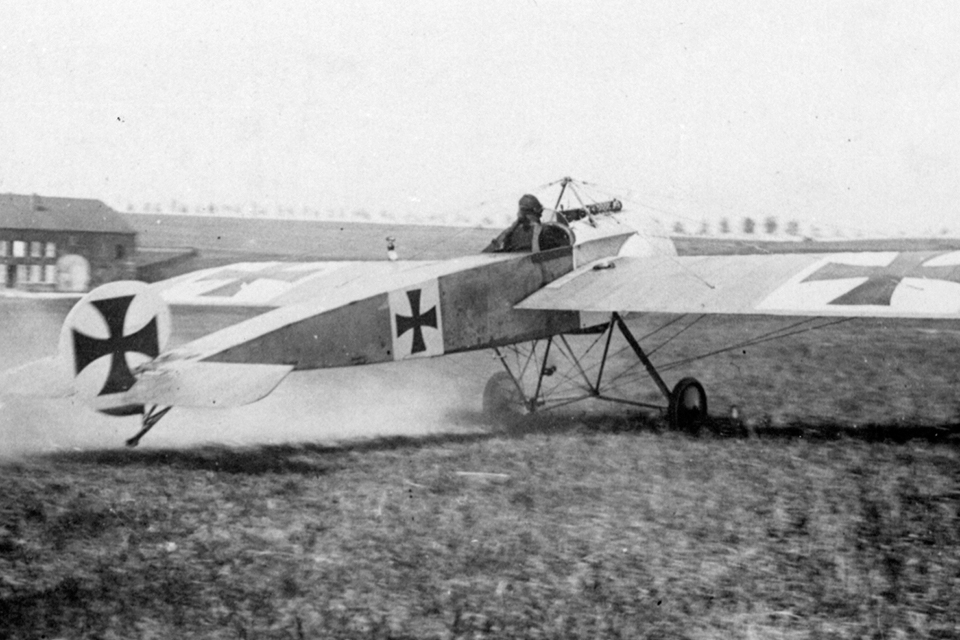

As the money rolled in, Fokker began improving the performance of the monoplane he had first designed in 1912. Unlike the wooden Morane-Saulnier, Fokker’s machine was made of welded steel tubing and powered by an 80-hp Oberursel engine.

Fokker recalled that on April 20, 1915, two days after Garros’ capture, he was summoned to Berlin, where he collected the deflector plates salvaged from the Morane-Saulnier, along with a Parabellum machine gun, then returned to his workshop. He later described the French design as “very cunning,” but he believed it could be improved. Within two days Fokker and his team of engineers had produced a synchronized gear whereby the machine gun’s rate of fire was controlled by the propeller’s revolution, so the bullets avoided hitting the blades. “We placed a cog on the prop, that lifted another rod with a spring that released the firing cock of the machine gun,” Fokker explained. “The prop passed a given point 2400 times a minute, so with this machine gun that fired 600 rounds per minute we needed only one cam on the prop. The pilot had a lever that enabled him to make contact between the cam on the propeller and the firing mechanism. That was all.”

On April 22, Fokker took his design to Berlin, and the next day gave a demonstration to a group of air service officers, using a gun fitted to a monoplane pulled by an automobile. All went well, and Fokker assumed he would receive instructions to fit the synchronization gear to all German aircraft. He noted, however, “In my overconfidence I had not taken into account the conservatism of the military mind.” The officers demanded to see the system in action in the air, so Fokker obliged them, but “still they weren’t happy and stated that the only way to test the gun was that I, not a German nor a soldier, would go to the front and shoot down a plane with it myself. Without leaving me any choice I was packed off to the front…[where] I was issued a uniform and an identity card, styling myself Lieutenant Anton Fokker of the German Air Force. In this manner I flew for several days, two or three hours a day, looking for an Allied aeroplane. Then one day I saw a Farman two-seater coming out of a cloud at 800 meters below me. At last I could show off the capabilities of the gun and I dived towards it.”

As he closed in for the kill, Fokker later claimed, his conscience got the better of him, and he broke off his attack. He returned to Douai, where he “quit the front line flying business.” Fokker said he had a furious row with Flieger Abteilung 62’s commanding officer, insisting that as a citizen of a neutral country he refused to be responsible for the death of a French pilot. As a compromise, Fokker offered to teach a German pilot how the synchronization gear worked.

“Lieutenant Oswald Boelcke, later to become Germany’s first ace, was assigned to the job,” Fokker recalled. “The next morning I showed him how to manipulate the machine gun while flying the plane, watched him take off for the Front, and left for Berlin. The first news which greeted my arrival there was a report from the Front that Boelcke, on his third flight, had brought down an Allied plane. Boelcke’s success, so soon after he had received the new weapon, convinced the entire air corps overnight of the efficiency of my synchronized machine gun. From its early skepticism headquarters shifted to the wildest enthusiasm for the new weapon.”

By July 1915, the synchronization gear had been fitted to Fokker’s single-seater M.5K Eindecker. Equipped with its forward-firing Parabellum, the monoplane—known as the Fokker E.I—became the German air service’s first fighter. Flying an E.I on August 1, Max Immelmann shot down a British two-seater, and by the end of that summer Royal Flying Corps pilots were referring to themselves as “Fokker-fodder.”

Not only did the Allies have no answer to the front-firing Eindecker, but at that point they had no pilots equal to Boelcke or Immelmann. Both men were brilliant technicians, with Immelmann inventing his famous climbing turn and Boelcke always attacking head-on, out of reach of his opponent’s gun. “To see a Fokker just steadying itself to shoot another machine in the air is, when seen close up, a most impressive sight,” wrote the RFC’s McCudden, who was fortunate to survive several such encounters.“For there is no doubt that the Fokker in the air was an extremely unpleasant-looking beast.”

For the rest of 1915, the Germans ruled the skies over the Western Front. French bombing sorties into German territory were halted in the face of the “Fokker scourge,” and British pilots’ morale dipped low, as they lost 49 pilots and observers to Fokker E.Is in the year’s last two months. Had McCudden not been sent back to England for training at the Central Flying School in January 1916, he might have been added to the list. As it was, when he returned to France in July, McCudden found superiority in the air war had shifted back in the Allies’ favor.

The French had introduced the Nieuport 11 Bébé sesquiplane (a biplane with the upper wing chord greater than the lower) in early 1916, which soon ended the Fokkers’ dominance. Small and swift with a good rate of climb, it was armed with a Lewis gun on the top wing firing over the propeller arc. The British quickly took delivery of a number of Nieuports, and over a four-day period at the end of May 1916, 19-year-old Albert Ball shot down three German aircraft while flying an up-powered Nieuport 16.

By this time the British had an impressive airplane of their own, the de Havilland D.H.2. Initially labeled the “spinning incinerator” because of a series of fatal spin accidents during training, the D.H.2 pusher proved agile and maneuverable in the right hands. Since the plane’s engine was in the rear, the Lewis gun in the nose had a clear field of fire for the pilot and, more important, an unlimited rate of fire.

Yet it would be another British pusher aircraft, the two-seater Farman Experimental F.E.2b, that was responsible for the death of Immelmann on June 18, 1916. Boelcke, having notched 40 victories, was killed in October of that year, and in November acting command of his Jagdstaffel 2 passed to his protégé, Manfred von Richthofen. Boelcke had schooled Richthofen in his “dicta,” a set of aggressive tactics by which fighter pilots hunted rather than patrolled. The Germans reasserted their dominance in the air in the spring of 1917, but by the end of the year they were struggling to manufacture an adequate number of airplanes due to metal and rubber shortages.

Richthofen had raised his score to 80 when he was killed on April 21, 1918, just a couple of weeks after Roland Garros rejoined the air war. The Frenchman had escaped from a German POW camp in February 1918 and made it back to his homeland. Desperate to atone for his failure to set fire to his secret weapon nearly three years earlier, he reenlisted in his old squadron and scored his fourth victory. But on October 5, Garros was shot down and killed while flying a Spad XIII.

By war’s end, Fokker was much in demand—except by his own government. Unwanted by the Dutch, he opened a factory in the U.S., and by the end of the 1920s was America’s largest civil aircraft manufacturer. Only the introduction of the all-metal Douglas DC-1 in 1933 ended the Dutchman’s dominance in American aviation.

Yet for all his achievements in civil aviation, it was in the military sphere that Anthony Fokker showed his greatest foresight. As James McCudden wrote of the Fokker E.II in 1918, “I must admit that the enemy deserves credit for first realising the possibilities of the scout type of aeroplane firing ahead, and for getting such machines in action before we had any machines ready to counter them.”

Gavin Mortimer is the author of Chasing Icarus: The Seventeen Days in 1910 That Forever Changed American Aviation. Recommended reading: The Origin of the Fighter Aircraft, by Jon Guttman; Sharks Among Minnows, by Norman Franks; Early German Aces of World War 1, by Greg VanWyngarden; and Aces High: War in the Air Over the Western Front, 1914-18, by Alan Clark.