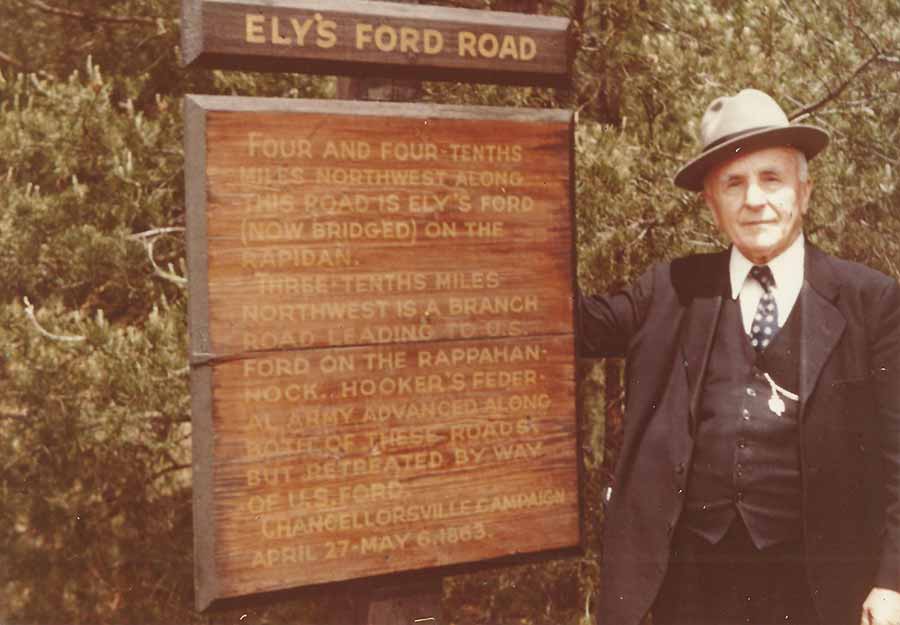

Fred Wilder Cross was so knowledgeable about the Civil War history of his home state of Massachusetts that a friend swore he could call the roll of many of its regiments from memory. He greatly admired the heroics of John Mosby—Cross owned at least six books on the Confederate guerrilla—and relished walking Civil War battlefields, often with a half-dozen or so friends from Virginia and Maryland, whom he called “The Battle-field Expeditionary Force.” Cross, who stood only about 5’2” or 5’3”, was always the “General” of the force, while his friends in the merry band he called “colonel,” or “major,” or a lesser rank.

In the decades before World War II, Cross traveled from his Cape Cod–style house near railroad tracks in South Royalston, Mass., to his second home in Florida. He went by bus because trains didn’t stop at battlefields. A first-class Civil War geek, Cross sometimes stayed in private hotels, but preferred historic homes on battlefields, where he enjoyed talking with descendants of those who lived at the sites during the war.

“He would not sponge on any of the battlefield folks he stayed with,” insisted Cross’ friend, Jim Clifford, a major in the expeditionary force, years later. And although he was a Yankee and “one hundred percent Massachusetts,” Southern hosts liked Cross. “I’ll say this for General Cross,” Clifford remembered, “he appreciated a good soldier and a brave man on either side and said so!”

And when you walked hallowed ground with General Cross, oh, what an experience that was. “He never stopped talking of what happened at that spot, at that instant, and who did what to who,” Clifford recalled of excursions with Cross in the 1930s and ’40s. “And he was waving his arms around and walking fast as he could travel! I mean, he was going a streak and you better listen to him and not interrupt the flow of facts.”

Cross’ resumé was impressive—he was a Phi Beta Kappa graduate of Williams College in 1900, a principal of Massachusetts high schools, and served as a member of the Massachusetts General Court in 1914-18 and as a state senator representing South Royalston in 1917-18. From 1918 to 1938, he was the military archivist for Massachusetts, compiling in his tenure a 6,500-page history of the state’s men who served during the Civil War.

But Cross’ real calling was as a “battlefield tramper.” Of all the battlefields Cross visited, Maryland’s Antietam and South Mountain were easily his favorites. His love affair with the Civil War history of western Maryland may have begun with his first visit there in July 1903, when he was 34. On summer vacation in 1919, he was accompanied to the state by his wife, Ida May, and daughters Bertha May and Dorothy. On other trips in the 1920s, he traveled to the region alone, documenting his experiences with a camera he had purchased in Fredericksburg, Va., in 1912.

“There are few places that I have visited or of which I have ever dreamed that have such a hold upon my heart as the picturesque hills and broad valleys of Western Maryland,” Cross wrote in 1926. “A most beautiful and romantic country, much of it rich in agricultural resources, its low mountains not too lofty to be ascended with ease, their summits presenting to the traveler most wonderful landscapes, every hill and road and stream abounding in historic associations; there is a lure to this section, which calls me back to it again and again.”

Eager to follow in the footsteps of Massachusetts soldiers, Cross walked Fox’s Gap, Crampton’s Gap, Turner’s Gap, Antietam, and other battlefields. He was keen to visit with the locals there, interviewing them about what happened in the area during the war. Sometimes, an interview subject had first-hand knowledge of wartime events.

In Sharpsburg, a resident told of aiding the clean-up at Henry Rohrbach’s farm, used as a makeshift hospital by the Army of the Potomac’s 9th Corps. The smell of the wounds of a dying Federal Maj. Gen. Isaac Rodman became so offensive in the house, the man told Cross, that he had to eat outside on Rohrbach’s porch. “Such incidents as these are not pleasant to relate,” Cross wrote, “but they represent the actual and terrible character of war.”

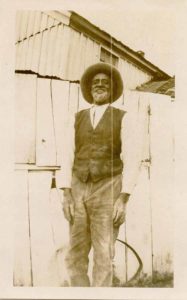

During a visit to Antietam in 1919, Cross spoke with Alexander Davis, who said he worked for the Nicodemus family at the time of the battle. The Nicodemus farm lent its name to battlefield landmark Nicodemus Heights, and “Uncle Aleck” told of burying soldiers days after the fighting. While digging graves alone, Davis told Cross he was approached by a soldier who asked if he had seen the body of Jimmie Hayes, a private in the 19th Massachusetts. Davis turned over a body in a blanket to reveal Hayes, who was identified by letters that had fallen from the 18-year-old private’s blouse. The soldier wept at the sight of his brother.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Cross’ real calling was a ‘Battlefield Tramper'[/quote]

“Incidents, ludicrous as well as pathetic, the old gentleman often told me,” Cross wrote about Davis, whose tales included the story of a stubborn battlefield bull. The night before major fighting erupted at Antietam, according to Davis, the “bovine majesty” refused to leave the barnyard of farmer David R. Miller, whose cornfield became site of horrific fighting on September 17. “In the morning, doubly excited and maddened by the artillery fire which began before dawn,” Cross wrote, “the bull smashed through the barnyard gate, and with flaming eyes and waving tail charged along through the entire length of the cornfield which that day won its bloody name, and never stopped in his mad course until he had reached the banks of Antietam Creek.” “Some of the soldiers,” claimed Cross, “who were lying on their arms in the edge of the cornfield, and in the early gray of the morning saw the terrible apparition sweep past, laughed over it until their dying day.”

In the 1920s, Cross gathered his experiences at South Mountain, Antietam and other battlefields into self-published reports that included the many photographs he had taken of the sites. He later shared the reports with friends. In his South Mountain report, Cross included a photo of Carlton Gross, whose family’s house was struck by Rebel artillery during the battle. “This little house was under fire during the artillery duel that proceeded the infantry attack, and a Confederate cannonball is preserved in the house, which was fired into it on the morning of September 14, 1862,” Cross wrote. “It came in at the right end of the house…pierced the westerly wall and the open front door, and wedged itself in the wall beside the door casing. I have a section of the shattered door casing in my collection at home.”

End of An Era

At Antietam, Cross met Jerry Summers, the last survivor of the six slaves who lived on the Henry Piper Farm in 1862. The farm and its slave quarters are preserved by the National Park Service. Cross later

typed up his description of the encounter:

“Jerry Summers was the last of the slaves of Sharpsburg. He was the property of Henry Piper who owned the famous Piper farm which was fringed on its northerly and easterly edges by the “Sunken Road” or “Bloody Lane”. In war time Jerry was carried off by the Union Army but later recovered by his indulgent master who regarded him almost like one of his children.

At Henry Piper’s death Jerry was given the use for life of a small cottage and garden plot facing the northerly stretch of the “Bloody Lane”, and here I found him in 1922 and in 1924….He died in 1925 aged about 76 or 77 years.”

Labors of love, the reports included images of Union Maj. Gen. Jesse Reno’s monument at Fox’s Gap; the Middletown house where 23rd Ohio Lt. Col. Rutherford B. Hayes, a future president, recovered from his South Mountain wounds; and a New York veteran’s visit to a farmer’s field where he had fought decades earlier. Cross’ Antietam report included a remarkable, undated image of the ruins of Dunker Church, flattened in 1921 by a violent storm. The church was rebuilt in time for the 100th anniversary of the battle, in 1962.

In one of his reports, Cross wrote: “I have prepared and annotated this collection of pictures because of the pleasure that I enjoy in revisiting in fancy the scenes, which hold for me such surpassing interest, and because of the feeling that, perhaps, long years to come my children may like to view again in these pages the scenes, which they once visited with me—scenes that are so intimately and pathetically connected with our Country’s history, and that have always filled and thrilled me with such absorbing interest.”

After Cross’ death in 1950, Jim Clifford and John Winters, a “colonel” in the expeditionary force, traveled separately from Virginia to their friend’s house near the railroad tracks in South Royalston. Cross had put his friends in his will, designating each to receive some of the many Civil War relics and books he had collected during his lifetime.

In wood boxes, Winters and Clifford packed up hundreds of books from Cross’ collection as well as cannonballs and projectiles by the dozens. Clifford was bequeathed a large, oak bookcase that held belt plates, bottles, buttons, pieces of exploded shells and scores of war relics Cross had collected from Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania battlefields.

Later, Clifford visited Cross’ grave, only 50 yards from the house where he was born. It says so right on his gravestone. “His tombstone [was] erected and carved to his specifications,” Clifford recalled in 1987. “It was tall, maybe four feet and five or six inches thick, and made of pure black slate. Beautiful and solid looking. His wife’s, too.” Next to his friend’s grave, Clifford found a marker for a homeless Union veteran, whom Cross had befriended and aided. “Wonderful of Mr. Cross,” Clifford wrote. “This alone should get him into the kingdom of heaven.”

John Banks is author of two books on the Civil War, Connecticut Yankees at Antietam and Hidden History of Connecticut Union Soldiers, both by The History Press. He also is the author of a popular Civil War blog (john-banks.blogspot.com/). Banks lives in Avon, Conn.