On the afternoon of June 17, 1861, a keen-eyed observer surveyed the scene before him and then dictated to a telegraph operator by his side. ‘This point of observation commands an extent of country nearly 50 miles in diameter,’ he said, and the operator obligingly tapped out his words with the telegraph key. ‘The city with its girdle of encampments, presents a superb scene. I have pleasure in sending you this first dispatch ever telegraphed from an aerial station, and in acknowledging indebtedness for your encouragement for the opportunity of demonstrating the availability of the science of aeronautics in the military service of the country.’

The man dictating the fulsome message was Thaddeus Lowe. He and the telegraph operator were in a gas balloon tethered 500 feet above the grounds of the Columbia Armory in Washington, D.C. The telegraph cables, which ran along one of the rigging wires to the ground, were connected to the War Department and the White House. Most important was the man on the receiving end of the message–President Abraham Lincoln. With a finely honed gift of salesmanship, Lowe was making his pitch to become the head of an aeronautic corps attached to the Union Army, using the balloon as a military machine.

The use of balloons in war was not really new. In a letter to a friend written less than three months after the first manned balloon flight in France in 1783, Benjamin Franklin suggested that ‘five thousand balloons, capable of raising two men each could not cost more than five ships of the line, and where is the prince who can afford so to cover his country with troops for its defense as that ten thousand men descending from the clouds might not in many places do an infinite deal of mischief before a force could be brought together to repel them?’

During the turmoil that followed the French Revolution, the government in France established a balloon corps attached to the army and a training academy for corps members. Its main purpose was to observe enemy positions and strength. Other European nations, including Denmark, Russia and Austria, either employed balloons in military actions or attempted to do so.

In the United States, the use of balloons by the military had been suggested prior to the Civil War, although they had not been utilized up to that time. During the Seminole War in Florida between 1835 and 1842, Colonel John Sherburne suggested to Secretary of War Joel Poinsett that balloonists could make night ascensions to spot the campfires of the rebellious Seminoles. Poinsett seriously considered the idea but declined to approve it after the military commander in Florida, Maj. Gen. Warren K. Armistead, said the terrain there was not suitable for balloon use.

During the Mexican War, John Wise, considered the ‘Father of American Aeronautics,’ devised a plan to take the city of Vera Cruz, which was guarded by the imposing fortress of San Juan de Ulua. Wise suggested fabricating a gas balloon capable of lifting 20,000 pounds, attaching it to a five-mile-long cable and flying the craft over the fortress so that 18,000 pounds of explosives could be dropped on it. Wise sent his ambitious idea to the War Department, but it appears to have gone unanswered.

Two months before he stood in the basket of the tethered balloon dictating his telegraphic message to President Lincoln, Lowe had made a lengthy flight that may have inspired his thoughts about the value of such aircraft to the military. Along with several other balloonists, he had set a goal of flying across the Atlantic Ocean during the summer of 1860. Lowe hoped to use the balloon Great Western to make the Atlantic crossing, but the craft burst during an attempt to inflate it on September 8. Like other aeronauts, Lowe believed that the wind at higher altitudes moved from west to east and would, once he reached the proper altitude, waft him easily across the Atlantic.

As he sought funding to replace Great Western, Lowe received advice about putting his theory of west-to-east winds to a safer test than would be possible over an open ocean. Joseph Henry, secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, suggested that Lowe make some test flights over the interior of the country. To do so, Lowe took his new balloon Enterprise to Cincinnati in the spring of 1861 and began inflation for a trial flight on the night of April 19, exactly one week after the Confederate bombardment of Fort Sumter.

While the winds did carry Lowe east, they also carried him south, and he received a less-than-friendly greeting after touching down near the border between South and North Carolina. When he attempted to land, Lowe was met by a group of armed men who advised him in no uncertain terms to take off again. As he did so, Lowe released a bag of sand ballast over the side, which caused one of the men on the ground to call out: ‘Hey, mister, I reckon you’ve dropped your baggage.’

When Lowe next attempted a landing, he found himself again in the midst of armed and unfriendly country people, some of whom apparently felt that the aeronaut was some kind of devil, if not in fact a spy. The unwelcoming committee decided to escort Lowe to Unionville, S.C., along with his balloon, which was deflated and placed in a wagon. After his arrival, Lowe was recognized by some better-informed residents, including the editor of the local newspaper, who had heard of his exploits as an aeronaut and gave him a letter of introduction to friends in the capital city of Columbia.

Upon his arrival there, he was arrested by the local sheriff and thrown into jail. He was released after a visit from government officials, including Mayor W.H. Boatwright, who drew up a passport for Lowe stating that he was ‘a gentleman of integrity and high scientific attainments.’

On April 26, Lowe and his balloon successfully made it back to Cincinnati via railroad. During his flight over South Carolina and the time he was in the state, he had observed activity by Confederate troops, and he decided to give up his idea of flying across the Atlantic and offer his services to the Union military. Murat Halstead, editor of the Cincinnati Daily Commercial, offered to write to Salmon P. Chase, secretary of the treasury, urging him to consider Lowe for service with the Union forces as a reconnaissance aeronaut. That contact later led directly to Lowe’s journey to Washington and his aerial telegraph message to Abraham Lincoln.

While Lowe may have had the inside track through his personal contacts with Lincoln, there were other aeronauts who also had been seeking to head up a nascent balloon corps. Among them were Wise, James Allen of New England and John La Mountain of Troy, N.Y. La Mountain had flown with Wise before the war but had taken to launching verbal barbs at both him and Lowe on a fairly regular basis. Indeed, the prewar relationships between the balloonists was one of considerable bickering and backbiting, which did not change during the period when each sought to control the Army’s aeronautical services.

Allen’s flight attempts were short and anything but sweet. On July 8, 1861, he was ordered to make reconnaissance flights over Confederate forces near Washington. Allen made an attempt to inflate one of his two balloons on July 9, but his gas generator failed to operate sufficiently to fill the vessel. Allen decided to use city gas to inflate his balloon and then transport the inflated balloon by wagon. During a subsequent inflation attempt on July 14, Allen’s smaller balloon burst. Later, his larger airship was inflated, and 60 men from the 11th New York Zouaves were assigned to move it by hand to Falls Church, Va. They had towed the balloon only a short distance when a gust of wind came up and blew it into a telegraph pole, destroying it. Exit James Allen.

Wise fared little better. He arrived in Washington on July 18. Placed under the command of Major Albert J. Myer, Wise also decided to inflate his balloon with city gas and have it moved in the direction of Manassas. Unfortunately, the movement of Myer’s troops was slowed by the necessity to keep the balloon out of trees that bordered their route. Frustrated by the slow pace, Major Myer ordered the balloon attached to a wagon, a move that Wise argued against. His objections were well founded. The faster pace set by the trotting horses caused the balloon to begin swaying, and it was promptly wedged in the branches of the roadside trees. Following one bad decision with another, Myer ordered the horses driven forward to free the balloon, which tore the fabric. A disconsolate Wise returned to Washington with his damaged balloon.

Wise made the necessary repairs to the shredded silk and successfully made an ascension over Arlington on July 25, where he noted the presence of Confederate forces and supposedly with his rifle fired the first hostile shot from an airborne contrivance in military history. Two days later, he was directed to take his balloon to Ball’s Cross Roads. During the journey, Wise noticed that the troops towing the balloon were hampered by their knapsacks and rifles, so he had them remove their equipment and place it inside the balloon’s gondola. The party soon encountered winds that made the balloon sway, and the mooring ropes came into contact with telegraph wires. The wires cut through the ropes and the balloon sailed away. It came back to earth eventually in damaged condition near a New York regiment whose members deflated it and sent it back to Washington, after first enjoying a snack thanks to the contents of the knapsacks found in the balloon’s gondola. Wise returned home to Lancaster, Pa.

Other than Lowe, the last balloonist making a bid to head up the Army balloon corps was John La Mountain. From his home in Troy, La Mountain had written to Federal officials seeking the post. His efforts at first were ignored, but he later received a letter from Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler offering him employment as a balloonist if his services proved to be of value. La Mountain arrived at Butler’s headquarters at Fort Monroe in late June 1861. The New Yorker criticized Lowe’s use of the telegraph and claimed he had a method of conveying intelligence from above. La Mountain also was critical of Lowe’s method of observing from a tethered balloon, instead advocating free flights over enemy positions.

La Mountain’s proposed system required that Union forces be located to the east of Confederates. While such a situation existed in the summer and fall of 1861, it was not likely to remain that way throughout the course of the war. Other limitations were a lack of communication with those on the ground and the necessity of ascending to high elevations to catch the air currents blowing east, which would make it difficult to determine where the original takeoff position was so that a landing close to it could be made.

By the fall of 1861, Lowe was firmly established as the head of aeronautical activities, with authority to construct additional balloons and portable hydrogen gas generators. With the new balloons on hand, La Mountain entered the picture once more. He had been flying his own gasbags, Atlantic and Saratoga, and both were suffering from age and use. In November, Saratoga was lost in a high wind and was never recovered. La Mountain coveted the new balloons. In December 1861 he requested that he be allowed to use one of them, alleging that Lowe was hoarding the craft. La Mountain’s attempt to gain use of one of the balloons was unsuccessful, but in February 1862 he tried again, claiming that two of the new balloons were sitting idle.

Lowe responded to his superiors that the two balloons in question were not idle. He went on to unleash a salvo at La Mountain: ‘A man who is known to be unscrupulous, and prompted by jealousy or some other motive, has assailed me without cause through the press and otherwise for several years… .He has tampered with my men, tending to a demoralization of them, and in short, has stopped at nothing to injure me.’ Major General George B. McClellan, the Union commander, had made previous attempts to get Lowe and La Mountain to cooperate with each other. By now he had had his fill of the bickering balloonists, and on February 19 he issued an order dismissing La Mountain from the service.

By the winter of 1861-62, Lowe had recruited a team of aeronauts for the corps. Among them were William Paulin (who had flown with Lowe prior to the war), John B. Starkweather, Ebenezer Mason and Ebenezer Seaver. Lowe also managed to sign on James Allen, along with Allen’s brother Ezra, Philadelphia lawyer and balloonist Jacob Freno, and balloonist John Steiner. Lowe hired his father, Clovis Lowe, as an assistant.

Thaddeus Lowe’s salary was $10 a day. Steiner, Seaver and Starkweather, who were sent to locations far removed from the Washington area, received $5.75. Allen, who functioned as an assistant to Lowe, was paid $4.75, while Ezra Allen, Mason, Paulin, Freno and Clovis Lowe each received $3.75.

Lowe now faced problems with members of his own corps. Paulin attempted to keep up his career as an ambrotypist in addition to his ballooning, and Lowe found it necessary to dismiss him in January 1862. In the spring, Mason and Seaver refused to fly because they had not been paid, and Lowe dismissed them. Their transgressions were mild in comparison to Freno’s. After several months of service in 1862, the Philadelphia lawyer-turned-balloonist was dismissed for being absent without leave, making disloyal statements, running a gambling operation and having a demoralizing effect on his subordinates.

John Steiner, who was a German immigrant, had been sent west to Illinois and became a victim of indifference from the commander there, Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck. Demonstrating an unfortunate fracturing of the English language, he wrote to Lowe: ‘I can not git eny assistance here. They say they know nothing about my balloon business… they even laugh ad me. Let me hear from you as soon as possible and give me a paper from Headquarters to show these blockheads hoo I am.’ The indifference was coupled with a failure to pay Steiner, who wrote again to Lowe: ‘I am here like a dog wisout a tail and I dond know ware I will be abel to draw my pay, for no one seams to know eny thing abought this thing. I am treed wis contempt and if I had the means to return to Washington I would strait today… now that I can git no pay out here.’ Steiner later returned to Washington and the Army of the Potomac, where his efforts were better appreciated.

Lowe’s corps enjoyed its greatest success with the Army of the Potomac. The corps’ primary objective was to observe and report on enemy activity. Other duties included warning of surprise moves by Confederate forces and reporting on the accuracy of artillery fire so that it could be corrected.

To prepare for an ascension, the balloons were sheltered from surface winds and attached to mooring cables that were worked through pulleys attached to fixed objects such as trees. When the aeronaut was in the basket and ready to go up, he would signal the ground crew, which would then slowly pay out the cables until the balloonist signaled them to stop. After the aeronaut finished making his observations, he once again signaled the crew members to pull the balloon back down to the ground.

While aloft, either the aeronaut or a military observer with him would note the number of the enemy or estimate it by the number of tents present in a given area. In the case of night ascensions, the number of fires observed might serve the same purpose. Even clouds of dust could have meaning. A dust cloud moving slowly along a road might indicate marching infantry, while a fast-moving cloud signaled the rapid movement of cavalry. With the aid of a telescope, balloonists could see 30 miles on a clear day.

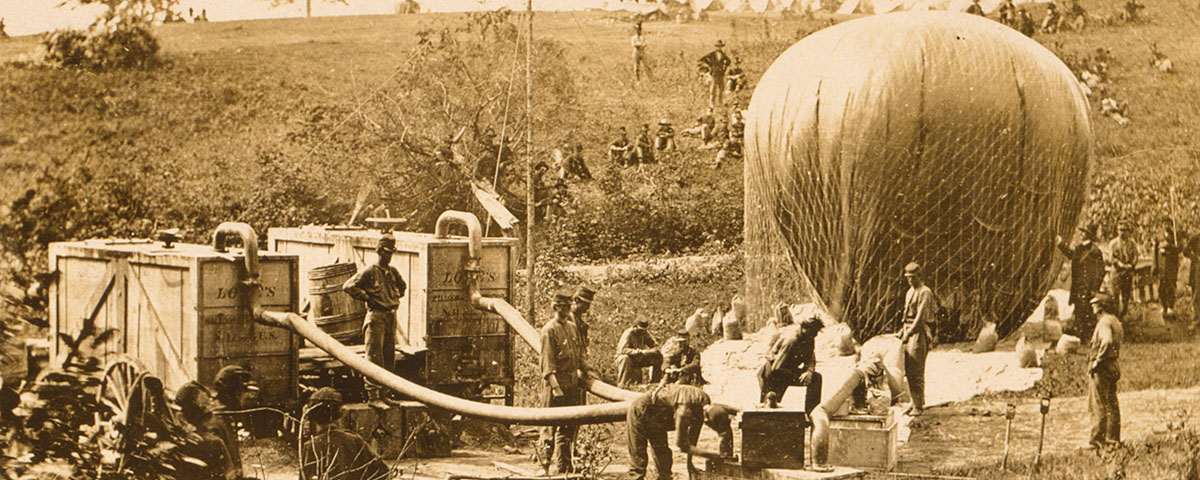

The need to tow a balloon, which had proved disastrous for Allen and Wise, was lessened by portable hydrogen generators designed by Lowe, 12 of which were ordered along with new balloons for the corps. The generators were designed to fit on an army wagon and consisted of a large tank containing shelves for iron filings. A funnel on top allowed the crew to add sulfuric acid to the tank. The hydrogen that resulted from the mixture was fed through a hose to a cooler before it was pumped into the balloon.

Some towing of balloons was still necessary, however, and the corps came up with a different way to transport them. The balloon boat George Washington Parke Custis was built by refitting an existing coal barge. The entire hull was covered with a flat deck for inflating and launching balloons, with one of Lowe’s portable generators also aboard. A tug towed the boat to various locations.

Confederate forces did not take kindly to having their actions and positions observed from above. They began trying to shoot down the aeronauts, winning Lowe the unwanted title of ‘the most shot-at man in the war.’ While none of the balloons was shot from the sky, Confederate gunners learned that they could more easily direct their fire at them when they were ascending or descending, since the tether lines dictated the area where they would be sent up and pulled down. Despite numerous Rebel efforts, the only casualty associated with the corps was the death of D.D. Lathrop, a telegraph operator who stepped on a concealed torpedo planted at the base of a telegraph pole in Yorktown, Va.

Artillery fire proved mainly to be a problem for ground forces situated near the balloons. In February 1863, David Hogan, an enlisted man with the 13th New Hampshire Infantry, was performing sentry duty when a shell aimed at Lowe, who was aloft, instead hit a cesspool near Hogan, covering him with the unpleasant contents. Hogan was not injured, but a fellow soldier noted dryly that ‘his clothes and appetite are utterly ruined.’

Confederate forces took actions on the ground to frustrate Union attempts to observe them from above. General P.G.T. Beauregard ordered his forces to conceal their fires at night and to pitch tents under the cover of trees. The Confederates also sought to confuse aerial observers with the placement of so-called Quaker guns–logs or stovepipe blackened to resemble the barrels of artillery pieces.

While the Union forces had the upper hand when it came to aeronautical activities, they by no means had a monopoly on employing balloons. Early during the Peninsula campaign, on April 13, 1862, Confederates under the command of General Joseph E. Johnston launched a hot-air balloon near Yorktown, Va. It was piloted by 21-year-old Captain John Randolph Bryan, who had volunteered since he was familiar with the terrain in the area. The tethered balloon was inflated by the heat and smoke of burning pine knots soaked in turpentine. Bryan made several flights, including one unintended free flight when his tether rope was cut in order to untangle a soldier whose leg had become caught in it just as Bryan was ascending. The free-flying balloon started to drift over Union positions but encountered a fortunate shift in the wind and landed safely behind Confederate lines.

These Confederate balloon flights were of short duration because the hot air quickly cooled and became denser. As a result, the Southerners looked with envious eyes at the Union’s fleet of gas balloons. In the summer of 1862, the Confederates would get a gas balloon of their own, although they would not have it long. The balloon, which would come to have a romantic legend associated with it, was known as the ‘Silk Dress Balloon.’

Former Confederate Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, in an 1886 article in Century magazine, appears to have gotten the story going. Longstreet wrote: ‘We longed for the balloons that poverty denied us. A genius arose for the occasion and suggested that we send out and gather together all the silk dresses in the Confederacy and make a balloon. It was done, and soon we had a great patchwork ship of many and varied hues.’ While Longstreet’s story created a fanciful picture of the sacrifices made by the women of the South, his tale was not accurate. The Silk Dress Balloon was made during the spring of 1862 in Savannah, Ga., by Captain Langdon Cheeves. Cheeves purchased 40-foot lengths of multicolored dress silks. After being sewn together and coated, the balloon was shipped to Richmond and first saw service on June 27.

The Silk Dress Balloon, inflated with city gas and moved to desired locations by railroad, made several flights. It was being transported in a deflated state aboard CSS Teaser when it was captured by Union naval forces on July 4, 1862. A second balloon made of dress silk was constructed that summer by Southern balloonist Charles Cevor and was in operation until the summer of 1863, when it was lost during the siege of Charleston. Overall, Confederate aeronautical activities were hampered by the Southerners’ inability to generate gas in the field.

The Union aeronautical corps was also plagued by problems throughout its existence. One involved the training of ground crews. A crew typically consisted of the aeronaut, a captain and 50 noncommissioned officers and enlisted men. The practice was to assign the crews from troops located near the site where a balloon was to be sent up. That custom led to a new ground crew being assigned whenever a balloon was moved–which meant the crew members had to be trained all over again. An aeronaut was lucky if he had the same crew for a few weeks.

An additional complication centered on the question of who was in charge. Lowe felt that the corps should be commanded by a commissioned officer, and he had himself in mind as that person, but in reality the aeronauts retained their civilian status throughout the war. That meant that had any of them been captured by the enemy, they could well have been charged as spies. Lowe was subject to the control of various field commanders as well as officious Washington administrators, and he often was unsure who was in charge. The balloon corps went from control by the Bureau of Topographical Engineers to the Quartermaster Corps, the Corps of Engineers and the Signal Corps. The constant shifting could not help but lead to problems.

Still another problem was officers who refused to use the balloon as a war machine. Conversely, those officers with firsthand experience with the balloons seemed to favor using them. Lowe took several generals aloft for flights, including McClellan, Irvin McDowell, Fitz-John Porter, William Smith and Samuel P. Heintzelman. All of them endorsed the use of balloons.

Lowe’s civilian status worked against him in terms of his inability to do things the ‘Army way.’ His account books and inventory procedures were frequently questioned by the War Department. In April 1863, Captain Cyrus B. Comstock was assigned to take charge of aeronautical activities. It was an assignment he took seriously, as he later wrote to Assistant Secretary of War P.H. Waterman concerning the balloon corps. ‘I found it as I thought, an unsuccessful experiment,’ Comstock wrote, adding that Lowe had been ‘acting without the knowledge or authority of anyone connected with the Army of which he is an employee.’ Comstock reduced Lowe’s salary from $10 to $6 a day and summarily dismissed his father from the staff. Lowe submitted a letter of resignation on April 12, 1863, but continued flying without pay until he left the service on May 6.

Lowe’s resignation left James and Ezra Allen as the sole remaining members of the corps. They continued flying but complained about the poor condition of their balloons in the weeks that followed. In June, they noted movement by the Confederates from Fredericksburg toward the Blue Ridge Mountains, the first steps of the campaign that culminated in the fight at Gettysburg.

There is no exact date marking the official end of the balloon corps, but there does not appear to have been any activity past the summer of 1863. Confederate artillery officer E.P. Alexander later said: ‘I have never understood why the enemy abandoned the use of military balloons early in 1863, after having used them extensively up to that time. Even if the observers never saw anything, they would have been worth all they cost for the annoyance and delays they caused us in trying to keep our movement out of their sight.’

After the corps was disbanded, its members went their various ways. Some continued their aeronautical activities, while others did not. John La Mountain flew for a time, but died in 1878. William Paulin took up photography full time.

John Wise pursued his goal of crossing the Atlantic–but without success. In the autumn of 1879, at age 71, he took off from Sterling, Ill., with a passenger, George Burr. Wise was never seen again, but Burr’s body washed up on the Indiana shore of Lake Michigan.

The only balloonists who flew again in a military capacity were the Allen brothers. As for Lowe, he was offered an opportunity to head up an aeronautical corps for Emperor Dom Pedro of Brazil to aid in that country’s ongoing war with Paraguay. Lowe declined but passed along the offer to the Allens, who flew reconnaissance missions for Brazil in 1867 and 1868. They returned to New England and, with other members of their family, continued flying until the early 20th century.

Thaddeus Lowe stopped flying in 1866. The pioneering balloonist made and lost several fortunes in the course of his life, but he died impoverished in 1913. Fittingly, the Lowe Astronomical Observatory in California is named after him.

This article was written by Ben Fanton and originally appeared in the September 2001 issue of America’s Civil War magazine.

For more great articles be sure to subscribe to America’s Civil War magazine today!