Hunkpapa Sioux leaders and Battle of the Little Bighorn veterans Gall and Sitting Bull, with the approval of the U.S. Army, were asked to join Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West show in the mid-1880s. Sitting Bull reluctantly agreed, but Gall replied, “I am not an animal to be exhibited before crowds.” By then, the two old friends were increasingly going in different directions.

Nine years younger than Sitting Bull, Gall was born about 1840 on the Moreau River, a branch of the Missouri in what would become South Dakota, and was given the name Matohinshda (Bear Shedding His Hair). His people, the Hunkpapas, were a small Lakota subdivision, consisting of only several hundred families. During a difficult period for the tribe, his mother discovered him eating the gallbladder of an animal killed by one of their neighbors and changed his name to Pizi, meaning Gall (or Man That Goes in the Middle).

As a youth, he had no father to teach him, which sometimes made life difficult. But his widowed mother early on recognized his strength and determination. When he was 3 years old and the tribe was moving toward the Powder River in search of buffalo, his mother placed him in a travois pulled by a dog. As she walked along beside him, digging roots as she went, a rabbit suddenly crossed their path and the dogs, including the one pulling Gall, bolted after it. Gall, gripping the dog’s tail in one hand and a travois pole in the other, hung on till the dog caught the rabbit in its jaws. Gall’s mother ran to her son and clutched him, and his grandmother poured some water for the tired dog. An older man who had observed the event declared it an omen—the boy would draw his people’s attention with more brave exploits in the future.

Gall grew into a strong, tenacious youngster. Once, at an intertribal gathering, a huge wrestling match was held, pitting the Lakota boys against Cheyenne boys. Gall found himself evenly matched against a young Northern Cheyenne brave named Roman Nose—probably the same Roman Nose who would distinguish himself in the Battles of Upper Platte Bridge (1865) and Beecher’s Island (1868), where he would lose his life. After all the other matches had ended and victors were proclaimed, Gall and Roman Nose were still locked in battle. Finally, when Gall had his equally tenacious opponent sprawled on the ground, Roman Nose’s mother stepped forward, placed a buffalo robe over Gall’s shoulders and declared him the winner.

Early on, Gall also made an enemy for life. Bloody Knife, whose mother was from the Arikara tribe and married to a Hunkpapa warrior, especially disliked Gall. Because Gall and the other Hunkpapa boys teased and tormented him, Bloody Knife felt like an outsider. At about 12, the extremely unhappy Bloody Knife and his mother left the Hunkpapas and returned to the Arikaras, but that did not end Bloody Knife’s hatred for Gall.

By the time he was a teenager, Gall had so distinguished himself in the tribe’s many battles that he earned a place in the Strong Hearts, the tribe’s most prestigious warrior society. Fellow member, Sitting Bull, played the role of Gall’s older brother and mentor. In time these two Hunkpapas would become among the best known and most feared of all Sioux warriors.

By his late teens, Gall had already demonstrated enough skill and daring to stand out as a leader among the Strong Hearts. In the late 1850s, Gall, Sitting Bull and several other prominent warriors founded the Midnight Strong Heart Society, an elite secret group within the Strong Hearts that gathered for late-night ceremonies.

During the summers of 1864 and 1865, Gall and his fellow warriors encountered and fought with many soldiers and settlers on the northern Plains. In the fall of 1865, food was in short supply and the Indians were lulled by the whites into believing peace was possible. In December of that year, Gall and his people arrived at a site south of Fort Berthold, in present-day North Dakota, prepared to trade. However, Gall did not know that perched on a scaffold inside the fort was his boyhood enemy, Bloody Knife, who was now a guide for the Army.

Obviously still harboring a grudge, Bloody Knife ran to the Fort Berthold commander—Captain Adam Bassett of Company C, 4th U.S. Volunteer Infantry—and offered to lead the soldiers to the brave responsible for killing several white men found dead and scalped in secluded spots along the river. Immediately, a lieutenant and a platoon of troopers were ordered to follow Bloody Knife to the Hunkpapa encampment, where they surrounded Gall’s tepee.

When Gall emerged from his lodge, he was struck by a bullet that knocked him down. A soldier dashed up and rammed his bayonet through Gall’s chest. Another stabbed Gall through the neck. As blood streamed from Gall’s wounds and mouth, the lieutenant walked over, bent down, examined the bleeding body, and proclaimed him dead. Still not satisfied, Bloody Knife stood over Gall’s prostrate body and shoved his gun toward his enemy’s bloodied face. However, before he could pull the trigger, the lieutenant pushed the gun aside, and its discharge tore up the ground alongside Gall’s head. Satisfied he had completed his mission, the lieutenant ordered his platoon and Bloody Knife back to the fort, leaving Gall’s body bleeding in the snow. The next morning when Bloody Knife returned to remove the scalp, he discovered that the body had vanished.

It is believed that the wounded Gall was taken by one of his wives to an elderly tribal woman skilled in healing, and together, after several months, they restored his health. Gall’s extraordinary strength and constitution no doubt aided in his recovery. The attack left him with ugly permanent scars on his body and a mind full of hatred for the white soldiers who ambushed him and for the Indian scout who assisted them. He was now resolved more than ever to defend the Hunkpapas and their land from the intrusions of settlers and soldiers. He further aimed to ensure that his people, in all future dealings, would remain united against the whites.

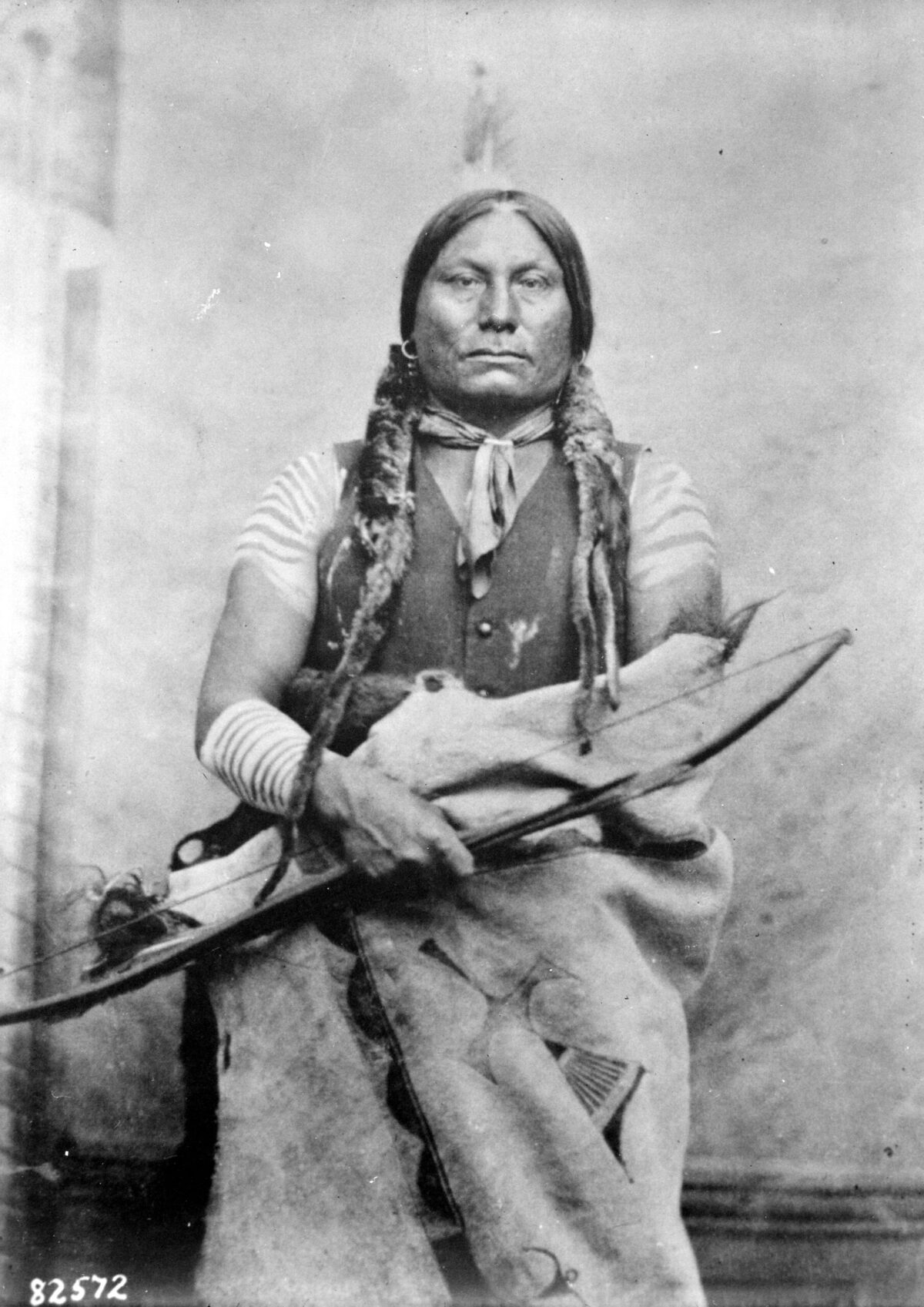

By the winter of 1866, many soldiers recognized Gall as the “Fighting Cock of the Sioux.” According to Joseph Taylor, a trapper who was friendly with the Indians, “Gall stood in his moccasins near six feet tall [actually he was just 5-foot-7], a frame of bone, with the full breast of a gladiator and bearing of one born to command. No senator of old Rome ever draped his toga with more becoming grace to the dignity of his position in the Forum than did Gall in his chief’s robe at an Indian Council.”

In July 1867, Congress passed a bill to make a new peace with the Indians. That fall a peace commission, which included Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman, came to Fort Laramie to talk with Lakota leaders. In spite of strong warnings by General Sherman, Lakota leaders Red Cloud, Crazy Horse and Gall intensified their raids. Finally, in 1868, the Indian attacks became so intense that travel on the Bozeman Trail leading to the Montana Territory gold fields became almost impossible. The government sent the well-respected Jesuit missionary Pierre-Jean DeSmet to persuade the leaders to meet again to talk peace. DeSmet reached the Hunkpapa camp near the junction of the Yellowstone and Powder rivers on June 19 and met with some success. Sitting Bull wouldn’t attend, but Gall would go and speak on his behalf.

Arriving at Fort Rice, in present-day North Dakota, on July 2, 1868, Gall and the others were offered a treaty identical to the one that had been signed earlier that year by the lesser chiefs. It called for the creation of the Great Sioux Reservation in the western half of what is now South Dakota. This reservation included only a fraction of the Lakotas’ traditional lands and excluded the Hunkpapas’ hunting grounds. Gall responded to the offer by saying:

“God raised me with one thing only, and I keep that yet. There is one thing that I do not like. The whites ruin our country. If we make peace, the military posts on this river [the Missouri] must be removed and the steamboats stopped from coming up here. Below here is the L’eau qui cours, which is our country. You fought me, and of course I had to fight you, too. I am a soldier. The goods you speak of I don’t want; our intention is to take no present. You talk of peace; if we make peace you will not hold it. We told the good father [DeSmet] who has been to our camp that we do not like these things [gifts]. I have been sent here by my people to see and hear what you have to say. My people told me to get powder and I want that. Now, there are many things that have happened that is not our fault. We are blamed for many things. I have been stabbed. If you want to make peace with me, you must move this post this year and stop the steamboats, and if you won’t, I must get all these friendly Indians to move away. I have told all this to them and now I tell you. One thing I forgot, I want 20 kegs of powder.”

After the other chiefs had their say, Gall, having made his terms for peace, went to the table and signed under the name Man That Goes in the Middle. Several other chiefs also signed, though Red Cloud would not do so until November and Sitting Bull never did. The treaty of 1868 would soon have dire consequences.

With Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse and other Lakotas, Gall spent the next few years drifting back and forth between northern Montana Territory and the prairies south of the Yellowstone, where they encountered fewer whites than in the past. The lull ended when in 1871 and 1872 the new Northern Pacific Railroad crews arrived to lay out the route through Indian lands.

In their attempt to stop this intrusion, Gall and the other major chiefs took up arms and brutally attacked the railroad surveying crews and their military escorts. Finally it got so dangerous that the surveyors proposed changing the planned route of the rail line. In the fall of 1872, Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan called for additional cavalry to bolster the U.S. forces in the region. In response, the 7th Cavalry—consisting of about 2,000 men, 40 scouts and close to 400 wagons, under the command of Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer—arrived in the spring of 1873.

In June of that same year, Custer and Colonel David S. Stanley, who had overall command, departed on another expedition into the Powder River country. By August they had reached the Yellowstone and were moving north toward the Tongue when the Indians spotted them. Gall and Sitting Bull, leading a sizable band of Hunkpapas and Minneconjous, immediately set out to destroy Custer. The troopers held them off and forced the Indians to retreat to an outcropping on the Yellowstone called Pompeys Pillar, where they forded the river on bullboats.

The next day, on the bank of the Yellowstone, more warriors arrived, and Gall tried to provoke the troops by riding back and forth before them dressed in a brilliant scarlet robe and a war bonnet. Finally, Stanley used his cannon to drive off the Lakotas.

Nearly a year later, in July 1874, Custer led a large expedition from Fort Lincoln to explore the Black Hills, which had been given to the Indians by the treaty of 1868. When he wired back that they had discovered gold, the news spread and miners were soon scrambling to reach the Black Hills. By the summer of 1875, U.S. officials knew that it would be impossible to control the flood of prospectors and the old treaty could not be maintained. Their answer to the problem was to buy the Black Hills back from the Indians.

Late in the summer of ’75, government agents invited the Lakotas to a council to discuss the matter. Some 400 Oglalas attended, and even Red Cloud was there, though he arrived late. On December 3, the U.S. issued an ultimatum that if the reluctant leaders did not return to the agencies by January 31, 1876, the U.S. Army would take action against them.

By June 1876, in the area between the Little Missouri and Powder rivers, some 3,000 Indians, including as many as 800 warriors, gathered around Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse and Gall. Because food at the agencies had run out or was in short supply, the Indians were hungry and had no choice but to return to their hunting ways. Following a herd of buffalo, the tribes would camp for a few days and then move on. It was inevitable that they would soon discover the 7th Cavalry and realize that a major campaign was being launched against them.

Because of recent successful raids on Army forts and the blocking of the sale of the Black Hills back to the government, the tribes felt that they were ready to counter any assault by the soldiers. Plus, the warriors’ fighting spirit was fueled by the recent celebration of the Sun Dance in which Sitting Bull had experienced the vision of a vast army of soldiers falling headfirst into an Indian village.

On June 17 while moving up Rosebud Creek, a large coalition of tribes, including Hunkpapas, attacked a column of more than 1,000 men, 120 wagons and several hundred mules led by Brig. Gen. George Crook. Gall was probably at the Rosebud but not as an active participant. The battle lasted several hours. In the end, though they had experienced fewer casualties, Crook’s soldiers took such a severe beating that they were forced to retreat. The Indians, basking in victory, moved to the Valley of the Greasy Grass (Little Bighorn Valley), where many other tribes joined them.

A few days later, while Gall’s followers were resting in their tepees, they were attacked by troops under the command of Major Marcus Reno. Gall’s tepee was one of the first to be hit, resulting in the death of two of his wives and three children. A large Hunkpapa war party soon charged the line of soldiers. Leading the charge, astride a black pony and wearing nothing but war paint, was Gall, who later said: “It made my heart bad. After that I killed all my enemies with the hatchet.” When a party of Oglalas joined the Hunkpapas, Reno retreated while Gall led his followers on to find the command of Custer.

The Battle of the Little Bighorn is one of the most written about Army defeats in U.S. history, and historians have offered countless versions and interpretations. Some credit Gall with being the battle’s leading chief. However, this is how he described his role in an 1890 magazine article by Francis Holley:

“I can’t say that I or anyone else was in command. I was sitting in my lodge, and all at once I heard the cry sound, ‘They are coming,’ and everybody rushed for their guns and horses. When I went for my horse they were running away. As soon as I caught them my plan was to try and head off the soldiers from the creek, so I circled around on the outside for that purpose. Everybody was fighting, and pretty soon I heard women on the hill calling, ‘Daycia! Daycia! [Here they are!]’ Then I saw some soldiers in that direction, and the women running that way too, and we kept circling around and around them. I caught a lot of soldier horses and hurried with them to my lodge, but when I got back every man was killed.”

After the battle, Gall and the Hunkpapas, along with other Lakota tribes, made their way north, hunting and fishing as they went, toward Canada. The Army, constantly in pursuit, engaged them at every opportunity, causing many tribes to surrender and return to the agencies. In May 1877, many of the Hunkpapas, along with other Sioux and Cheyenne tribes, crossed the border into Canada, where the government allowed them to live peacefully. For the next several years the Lakotas, in search of food, drifted back and forth across the border. In August 1880, Gall and his hunting party came across a herd of cattle being led by several American ranchers. Among the ranchers was Edwin H. Allison, an American scout and interpreter whom Gall had known for several years.

Allison fed the hunters and tried to convince Gall that it would be better for him and his people to surrender to the Army and become agency Indians. After weeks of careful thought and watching his people grow hungrier and hungrier, Gall led his 23 lodges away from Sitting Bull’s camp and on November 25 reached the Poplar River Agency, near Fort Peck, in Montana Territory. By December his followers had grown to 75 lodges and had become a security concern for the agent in charge.

On December 24, Major Guido Ilges, leading several companies of soldiers, arrived to make sure Gall and his followers remained docile and would continue on to Fort Buford. Gall met with Major Ilges and insisted that he be allowed to spend the rest of the winter where he was. The next morning, the Army attacked. Neither Gall nor his people offered much resistance. Thus, after nearly 20 years of fighting the white men, Gall was finally defeated and forced to walk, in snow and subzero weather, to Fort Buford. Steamboats later carried him and his people to the Standing Rock Agency, near the southern border of present-day North Dakota.

The agent at Standing Rock, short, strong-willed James McLaughlin, recognized Gall as a leader having the full respect of his people. The agent did not have so much respect for another Standing Rock resident, Sitting Bull. Therefore, McLaughlin made Gall and another warrior, John Grass, the agency’s head chiefs.

Gall adjusted quickly to reservation life. In 1884 he represented the Sioux at the New Orleans Exposition. Four years later, he was one of several envoys to Washington, D.C. Upon his return, in 1889, he was appointed a judge of the Court of Indian Offenses and continued to have an important impact on the lives of his people. A few years before his death, he told his followers, “I think it better for us to live as we are now living rather than create trouble, not knowing how it will end.”

On December 5, 1894, Gall, at age 54, died at his home near Oak Creek, S.D., about 50 miles from where he was born. Some say his death was caused by an overdose of antifat medicine. Some believe it was from the lingering ailments of his injuries at Fort Berthold. Others believe it was a combination of the two.

Originally published in the June 2006 issue of Wild West.