At times, criminal justice in the Old West was almost as painstaking and thorough as we find it today. For instance, due process of law got its due in Montana in the interesting and strange case of William Gay, a frontiersman who became a well-to-do businessman — and then a killer.

When Gay was arrested, a Colt Model 1878 double-action revolver was in a snug-fitting shoulder holster worn under his coat, and an 1875 .32-caliber New Line Model Colt five-shot derringer with nickel finish and mother-of-pearl grips was hooked to his belt.

After witnessing Gay’s execution by hanging on June 8, 1896, in Helena, Mont., an old acquaintance, Idaho Sheriff William Ryan, remarked: “Bill Gay was one of the bravest men I ever knew, and I have seen many brave men during life in the West. He had been raised on the frontier and was a typical plainsman — one of the class of men now fast dying out, who were always ready to use a gun.”

Born in Virginia in 1844, Bill Gay had become a Westerner by age 14. In the early 1870s when he was about 30, he was a stout, adventurous man engaged in freighting supplies to Idaho mining camps after the goods were offloaded from Missouri River steamboats at Fort Benton, Mont. The Helena Daily Herald newspaper said in an 1895 article that Gay had once helped rescue a female survivor from a wagon-train party that had been massacred, and had once scouted for George Armstrong Custer‘s 7th Cavalry. Later, Gay, with his brother Al and John Nelson, spent a winter traveling among and trading with the Sioux.

On the day of his execution in 1896, the Herald published a story that said Gay had also been a cattleman and mail carrier.

Gay, according to Sheriff Ryan, was one of the first white prospectors to enter the Black Hills of the Dakotas in the mid-1870s. By the time he left Deadwood in the summer of 1876, Gay had $100,000 in gold. He did not go far. He and brother Al capitalized on the influx of people into Dakota Territory to organize a new town, which they called Gayville. Bill Gay operated a saloon and gambling hall in the town that bore his name.

“His greatest fault was in helping every poor prospector, miner and the poor people until he was almost beggared himself,” recalled Gay’s daughter Maud in a Helena Daily Independent article published 11 months before her father was hanged. “He will be remembered by hundreds of the old pioneers with feelings of gratitude. But, unfortunately, like most all early pioneers, they are broke or are not in a position to assist him now.”

Gayville was hit by several damaging fires, but a more serious problem surfaced for Bill Gay in 1877. That spring, Gay killed a chap named Forbes for being too attentive to Mrs. Gay. After Gay was found guilty of second-degree murder and sentenced to 15 years in prison, his many friends in Gayville and Deadwood wrote a petition and reportedly spend $40,000 to try and secure his early release. It worked; Bill Gay was pardoned after serving only one year. When he arrived home in Gayville, he was greeted with a brass band.

Despite the reception that greeted Bill’s return, he found things changing for the worse in Gayville. The South Dakota community was in decline, and its future did not look bright or golden.

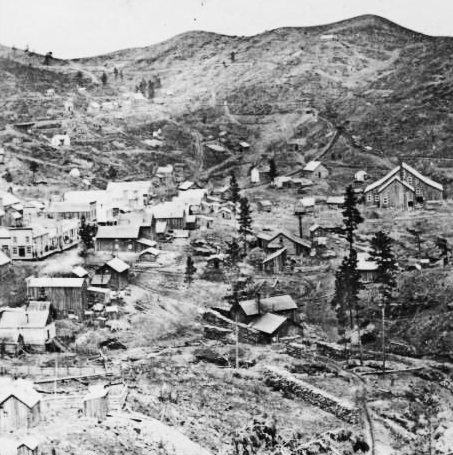

In 1889, Gay and his family, along with his brother-in-law, Harry Gross, relocated to Castle in Montana’s Meagher County. At first, Gay did carpentry and odd jobs for others. Eventually, he moved to a ranch 6 miles south of Castle, but he built his house on land also claimed by N.E. Benson, who owned the Castle Reporter and was chairman of the Republican Party for the area. Reports soon surfaced that Gay and Gross had robbed a store in northern Wyoming. Tensions further increased when Benson’s newspaper published an article that suggested Bill Gay had an incestuous relationship with his daughter.

After a fire destroyed the Castle Reporter print shop, some citizens alleged that Gay was responsible. In May 1892, Gay began to receive anonymous threatening letters and found notes attached to his front door. The last message said, “The citizens of Castle take this method of informing you that unless you get out of the country you will be killed.” There was no signature, just the cryptic old Montana Vigilante symbol, “3-7-77.” Gay ignored the threat.

Gross was arrested on April 4, 1893, while resisting a search warrant served on him in an effort to find evidence to pin the Wyoming robbery on him. Gross escaped from custody after persuading the deputies to allow him to stop at Gay’s ranch to explain his situation and to get Bill to help him secure a bail bondsman.

Later, at Gay’s trial, Constable Peter Westbrook testified that following Gross’ escape, Gay had told him he was tired of being hounded by the citizens of Castle and that he had not stolen from anyone in Castle.

“There was not men enough in Meagher County that had sand enough to arrest me,” Westbrook quoted Gay as saying. The constable added that when Gay made the statement, he was carrying a .45-120-caliber Sharps buffalo rifle. Not long after Gay allegedly said that, he and Gross were freeing a wagon from a mudhole not far from Gross’ ranch when some deputies showed up intent on arresting them.

Who fired the first shots in a brief exchange has been disputed, but, in any case, the deputies left empty-handed. Meagher County Sheriff James O’Marr then organized a posse of several local citizens and enlisted as his deputies an ex-sheriff named William Rader and the same Peter Westbrook who would later testify at Gay’s trial.

As the posse closed in on Gay and Gross, Sheriff O’Marr split his force, probably wanting to encircle the two men. Rader and Westbrook followed up the trail and soon encountered Gay and Gross, who were resting along a creek while their horses grazed.

“Throw up your hands!” Rader shouted. But tather than comply, Gay and his brother-in-law took cover. The two possemen shouted again and then began firing. Rader maneuvered to a higher position and got off a good shot.

Seeing Gay fall with what turned out to be a leg wound, Rader told Westbrook, “You hold the horses; I think I have broken that fellow’s back.”

Later, Westbrook said that his gun “choked” and that the fighting had to be done by Rader. As Rader approached the fallen Gay, according to Westbrook’s testimony, Harry Gross shot the lawman in the back, killing him instantly. Westbrook then retreated, allowing Gay and his brother-in-law to once more escape.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

After Westbrook located Sheriff O’Marr and the rest of the posse, the group recovered Rader’s body and then continued the pursuit of the two wanted men. Correctly assuming that the two fugitives were headed toward the Musselshell River country 80 miles north of Castle, the posse once more caught up with Gay and Gross. The outlaws hastily dug a shallow rifle pit in a stand of willow trees and opened fire on the posse. In the ensuing gunfight, Deputy Sheriff James Macke was killed. With a dying declaration, Macke told the other officers it was Bill Gay that had shot him, although Gay would insist later that it was Harry Gross who had killed Macke. Again, both Gay and Gross were able to get away into the wilds of Montana. The posse, at this point, had run out of steam.

Gross was never brought to trial, but Gay was apprehended in California in the spring of 1894, almost a year after the two lawmen were killed. Someone who had known Gay and was aware he was a wanted man had tipped off the law. During his year on the run, Gay had traveled a circuitous route from Montana into Utah and Nevada. He had changed his name and worked for a mining company, but his efforts to again become a rich man through prospecting had not paid off. He eventually had found his way to Providence, Calif., and was reshoeing his horse there when two men approached him. Before Gay knew it, he found himself at gunpoint and in handcuffs.

After being returned to Montana, Gay stood trial in Lewis and Clark County — a change of venue ordered because of the threat of violence in Meagher County. A lengthy court proceeding ended in a guilty verdict. For the shooting death of Deputy Macke, Gay was sentenced to death by hanging. His lawyers took the case to the state Supreme Court, which denied the application for a new trial after a lengthy review. A motion was then filed with the U.S. Supreme Court, but the court refused to grant a hearing after deciding that there was no federal question involved in the application. Gay saw his execution date postponed three different times during his incarceration.

After receiving petitions with the signatures of 4,500 people urging leniency, as well as letters from Gay’s friends who felt the sentence was too severe, Montana Governor John E. Rickards ruled on the latest scheduled date of execution.

“I am fully satisfied, after a most thorough examination, that Mr. Gay had the benefit of a fair and impartial trial and that he was accorded all the rights allowed him under the law and is seeking to evade punishment for the crime he had committed,” the governor said. “One of the most appalling crimes in the list of punishable offenses is the murder of officers of the law in the discharge of their duties. To permit sympathy to interfere with the punishment of a man found guilty of such a crime is to weaken the safeguards thrown around the public.”

After the governor turned down the request for leniency, Gay responded with a published letter: “I am innocent and will with my last breath say so. Could the spirit of Macke come here he would say so, too, and the cowardly curs who swore my life away should feel ashamed of their low and contemptible acts. I mean O’Marr, Thoe, Sarter, Denny McGrail and more especially Peter Westbrook and George Williams… I am not afraid to meet death in any form. I never knew what fear was. I have risked my life a hundred times or more to save people from harm, people I never saw before, or since, but that don’t count for anything among the race today. A hundred years ago, people appreciated such favors and deeds. I have seen men burned at the stake and I would rather a thousand times over be burned than die like a sheep killing dog. My enemies, the cowardly curs, may rejoice at my fate, but the time will come when they will remember me and they will die a harder death than mine.”

During the morning of June 8, 1896, Gay was readied for his execution. Having been ill for a 36-hour period prior to the appointed time, he was given an injection of morphine before leaving his cell. He asked for a drink of whiskey and got it; he then offered the sheriff a drink, but the lawman declined. On the way to the hangman’s noose, Gay was greeted by his friend Sheriff William Ryan, who had come to witness the hanging.

“Goodbye, Bill,” Ryan said.

“Goodbye,” Gay replied, “but if I hadn’t been sick, I would feel better, don’t you know.”

The condemned man was moved into position, and Montana Sheriff Jurgens placed a black hood over his head. Next came the noose, which was attached to a 460-pound weight.

“Now as I said, it seems hard that I have to die this way,” Gay said. “I want to see the sun as long as possible. I will never see another one and I want to see this one as long as I can. Gentlemen, you are witnesses to a man being murdered. I am murdered right here.”

He then turned to the sheriff and said, “You’ve got to get the rope around haven’t you? Make it solid.”

It was solid enough. The trap was sprung, and frontiersman Bill Gay swung off to oblivion.

This article was written by E. Dixon Larson and Al Ritter and originally appeared in the June 1996 issue of Wild West.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.