For one Union regiment, the dreadful casualty count from Pickett’s Charge included numerous desertions

When we think of deserters in the Civil War, we imagine an army’s cowards, scoundrels, and riff-raff who abandon their comrades to save their own skins. While some fit this profile, the reality is that what prompted men to desert was often more complex than the simple broad brush that is usually applied. A spike in desertions typically followed every major battle, including Gettysburg. Even the best regiments experienced desertions. The 69th Pennsylvania Infantry is an example. It was an excellent unit, but between July 5 and July 17, 1863, it lost 11 soldiers to desertion. Their stories can provide us some idea of desertion’s complexities.

The 69th was engaged July 2–3 on Cemetery Ridge. On the 3rd, its position was struck by the full fury of Pickett’s Charge. The famous Copse of Trees stood directly in the 69th’s rear. With Confederates surging forward in their front and on both flanks, the regiment held, though the cost was high. In the two days of combat, 40 were killed, 80 wounded, and 17 captured, just more than 50 percent of the regiment’s strength.

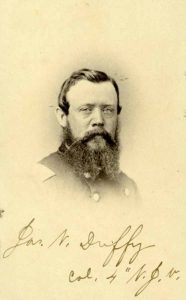

The first to desert was Private George Haws of Company A, a 29-year-old plumber in civilian life. Haws was Major James Duffy’s orderly. When Duffy was seriously wounded July 3, Hays accompanied him to his home in Philadelphia. Once the major was safe, Haws disappeared into the city, never to be seen by his regiment again. He apparently went straight to the docks and, probably under an assumed name, signed on as a merchant sailor, concluding perhaps he would not survive another battle like Gettysburg.

Each man had his limit of how much combat he could endure without breaking, and Haws may have reached his in the terrifying action of July 3. That may have also been why Patrick Harvey of Company F deserted on July 6. Harvey’s company was overrun by Pickett’s men on July 3, with nearly every man killed, wounded, or captured. Where Harvey went is unknown, but he returned to the regiment on September 27 carrying his rifle and equipment. The Army court-martialed him and docked his pay, but no more. He served out the remainder of his enlistment without incident. Even though both men were in the battle, you’ll not find Haws’ name on the 69th’s tablet on the Pennsylvania Memorial; Harvey’s is. Deserters who returned were deemed worthy of having their name on the monument. Those, like Haws, who never returned were omitted.

A third soldier deserted the regiment on July 7, three more on July 11, one each on July 12 and 13, and two more on July 14. The 11th deserter was John Harvey Sr., on July 17.

Not all of these were guilty. Patrick Lundy straggled during the regiment’s march July 12, was captured by Confederate partisans, then rescued by Union cavalry during a skirmish. In the action, Lundy lost two fingers and wound up in a Washington, D.C., hospital. Word failed to reach his company commander, and Lundy was carried on the regimental rolls as a deserter until August, when he wrote his commander that he had not deserted but was wounded and in the hospital.

John Eckard of Company A was one of those to desert on July 11. He was 27 and a laborer before the war. He had already deserted once, on August 28, 1862, and returned on April 29, 1863, under a pardon President Lincoln issued to entice deserters to return to their regiments. Other than the period he had absconded, Eckard served in every battle in which the regiment participated. The Army tracked him down in Philadelphia in September. He was court-martialed, sacrificing all back pay, and was ordered to pay the government $10 a month of his wages for nine months. Eckard, like many in the regiment, was poor and the sentence hit him hard financially. He appealed to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton in March 1864 to be allowed to reenlist as a veteran volunteer. Because of his sentence, he had been denied this right. “You will be rendering a never to be forgotten favor on [me],” by approving the request, he wrote to Stanton. The secretary approved and Eckard reenlisted. It did not end well for him. The private was captured at Ream’s Station, Va., on August 25, 1864, and sent to North Carolina’s Salisbury Prison, where he soon died of disease.

From his record, William Farrell was a good soldier, but he had quarreled with Colonel Dennis O’Kane, the 69th’s commander. Farrell was wounded in the July 3 fighting and likely didn’t know that O’Kane had been killed. Determined he would not return to serve under O’Kane again, Farrell slipped out of an Army hospital in Philadelphia on July 13 and made his way to the city’s Marine Corps recruiting office. He enlisted for six years under the name William Giblin, served out his enlistment honorably, and was discharged in 1869. Years later he applied for a pension for disability from his service in both arms. When the remarkably thorough Pension Office investigated, officials discovered he had deserted from the 69th Pennsylvania but had served honorably in the Marines. His pension for service with the 69th was denied, but approved for the Marine Corps.

Other than Eckard, who had previously deserted, each of these deserters had good records as soldiers. They had done their duty and been present in all the regiment’s battles and campaigns. Something about Gettysburg, or perhaps the cumulation of everything leading to Gettysburg, tipped the scale in them. Each had his own reason to desert his comrades, a decision that could not have been easy. They were not scamps or cowards, but men who had reached the end of what they could bear. All paid some price for their decision. Their story is a reminder that the war’s casualties were not just the killed, wounded, and captured.

Scott Hartwig writes from the crossroads of Gettysburg.