Eighty years ago, the first Free French execution opens some conservative eyes to the real terms of the Nazi Occupation

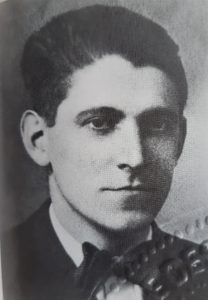

Count Honoré d’Estienne d’Orves followed a classic path for the son of a noble French family: top schools to the elite Polytechnique, naval officer to ship commander, practicing Catholic to marriage and five children. His profile was a perfect match to those the ultra-conservative Vichy government wanted on its side during the 1940-44 Nazi occupation of France.

So when the German authorities stood d’Estienne d’Orves in front of a firing squad and shot him dead on Aug. 29, 1941, it was also a warning to the conservative classes who had been willing to play Marshal Philippe Pétain’s game of collaboration up to then. If they could kill d’Estienne d’Orves, no one was out of range.

“His death opened the eyes of many to the reality of Hitler,” said François Guy Trébulle, mayor of the French town of Verrières-le-Buisson, where d’Estienne d’Orves was born and where he was buried. The town, just south of Paris, turned out on Sunday’s 80th anniversary date for a ceremony honoring their native son.

Trébulle said that today, d’Estienne d’Orves represents not only a boldly taken resistance engagement, but that his last and most enduring act was to open a door to reconciliation. “He did everything he could for reconciliation,” Trébulle said.

D’Estienne d’Orves’ execution occurred during a wave of rising tension against the Germans; August 1941 was a pivot point in the Occupation on several levels. Following the Russia-Germany breakup in June, young French communists leapt into action, organizing resistance groups and even holding a brief protest in Paris on August 13. At the same time, Vichy officials were writing a new law that set the death penalty for any communist activity, such as publishing tracts, organizing groups or protesting. Two 20-year-old demonstrators arrested on the 13th were executed on August 15. In revenge, a comrade of theirs then shot and killed a German naval cadet in the Barbès-Rochechouart Metro station on August 21, the first assassination of a German since the Occupation had begun more than a year before. France was turning into a vengefest, with the German police taking dozens of hostages for each German attacked, and threatening to kill them. Many of the hostages were known communist activists, though the party itself had been banned in 1939.

For the French, d’Estienne d’Orves had nothing to do with this. But he happened to be in prison, condemned to death for espionage, when the Germans declared that anyone in prison for any reason could be shot as a hostage in reprisal for attacks. D’Estienne d’Orves had joined the Free French in London after the French navy was disabled by the British in July, and was sent with a team into the Brittany region of France to organize a clandestine Resistance group he named Nemrod. The team arrived on Dec. 21, 1940, and d’Estienne d’Orves, working under the pseudonym Jean-Pierre Girard, began setting up contacts and information networks.

They were there barely a month before the team’s radio operator sold them out to the German intelligence service in Nantes. Alfred Gaessler was an Alsatian with a drinking problem, overheard complaining that Churchill didn’t pay enough. His indiscretion was such that he invited bar buddies to his room to see his radio set. The rest of the team warned d’Estienne d’Orves to get rid of him, but before he could move, the Abwehr was on them. Twenty-six members of the group were arrested.

At the Cherche-Midi Prison, d’Estienne d’Orves soon became an anchor of support for the dozen Resistance prisoners held in cells around him. In memoirs, surviving prisoners noted his generosity of spirit, his efforts to keep morale high, his empathy reaching through iron doors and stone walls. Agnès Humbert, an art curator arrested for resistance work, wrote that he conducted an imaginary flag-raising ceremony every morning, all of them quietly singing the Marseillaise in their cell, ending with “Vive le général de Gaulle!” When the guards were gone, d’Estienne d’Orves put together “Radio Cherche-Midi” in which everyone contributed anecdotes, memories, songs or poems, while he played the role of broadcaster. They spoke through ventilator holes or under the door crack, lying on the floor.

After a 14-day trial in May 1941, he and two companions were convicted of espionage and sentenced to death (a total of nine members of the group received death sentences on various charges). He told Humbert he had been happy to have seen his wife at last and learned that his last child, Philippe, was a healthy six-month-old. Humbert was by then in the cell next door to his, and they could speak easily through the wall. “Despite everything, we joked around, we described ourselves physically to each other so as not to be disappointed when we get to see each other at my place […] Because I do not want, no, I do not want to believe that he will be executed, and I sense that it amuses him to play the game, to think of the future that he perhaps will not have.”

Even Vichy was shocked by his death sentence. Admiral François Darlan, former head of the French navy then serving as Pétain’s prime minister, employed his excellent relations with the Germans to try to get a pardon for d’Estienne d’Orves. So did both the Abwehr colonel who arrested him and the German magistrate who had sentenced him. Hitler, however, incensed by the increasing attacks on Germans in France, flatly refused and ordered the execution carried out immediately.

At dawn on August 29, d’Estienne d’Orves, Yan Doornik and Maurice Barlier were driven to the fort at Mont Valérien. They asked not to be blindfolded or have their hands bound. They would look their killers in the eye. Before the order to fire was given, d’Estienne d’Orves offered forgiveness to the German magistrate, present at the execution. He had written to his sister the night before, a last missive of love and compassion. “No one should dream of avenging me. I desire only that peace and greatness be returned to France. Tell them all that I die for her, for her complete freedom, and that I hope my sacrifice will serve her.”

D’Estienne d’Orves, the first military officer and first Free French agent to be executed, had spent his seven months in prison writing in a journal and letters to friends and family. Mayor Trébulle noted that because of these documents, his selfless nature and generosity of spirit were on evidence. In keeping, the town of Verrières-le-Buisson has been twinned with the German town of Hoevelhof for 50 years, and the latter’s mayor, Michael Berens, attended the ceremony on Sunday. He said that d’Estienne d’Orves’ last act of pardoning his executioner “was the beginning of German-French forgiveness.”

Both towns have been working to keep the message of d’Estienne d’Orves alive. In Verrières, the primary school is named for him, and in Hoevelhof, the school is named for Franz Stock, the German army chaplain who counseled d’Estienne d’Orves and wept at his death. On Sunday, members of the Verrières’ Children’s Municipal Council read from his letters as part of the ceremony. A group from his alma mater, the Polytechnique, also participated as color guard and chorus.

D’Estienne d’Orves’ name has been given a special place in French memorials of the war. Across the country, more than 80 streets, schools, ships and halls have been named in his honor.

This article was originally published in the