The story of Creede, Colorado, like that of many other Western boomtowns, is equal parts fact and fiction. It is known that on August 26, 1889, experienced miners Nicholas C. Creede and George L. Smith emerged from their tent and hiked up a Rocky Mountain gorge to do what they’d been doing for decades—seek their fortune. About midday, with a shadowed, narrow view of tall evergreens dotting the gray canyon’s steep walls, they stopped for lunch beside East Willow Creek, where mountain trout plied the cool, swift water. Legend has it Creede, who’d been pecking at the rocks with his geologist’s hammer, suddenly stopped, squinted at the glistening chips in his hand and exclaimed to Smith, “Holy Moses!” So, the story goes, went the birth of the Holy Moses Mine and the town of Creede.

As settlers in ox-drawn covered wagons plodded across the plains in search of wide-open spaces where they could grow crops and children, fortune seekers like Creede and Smith clambered over one another in search of ore, hoping to be the next one to strike it rich. In their wake such men ultimately left hundreds of ghost towns across the American West, including dozens each in California, Alaska, Utah and Colorado. And though almost every ghost started life as a boomtown, perhaps none boomed louder or fell harder than Creede.

A Colorado Territory gold strike in 1858 triggered the Pike’s Peak Gold Rush, lined Denverites’ pockets and beckoned prospectors to the Rocky Mountains. After the Civil War new railroad lines brought even more miners from every corner of the country. In their quest for gold they often found silver. Though it was a far less valuable ore, silver strikes in the mid-1870s in Leadville fueled a modest boom. In an odd combination of cause and effect, the 1878 Bland-Allison Act and 1890 Sherman Silver Purchase Act, which required the government to buy and coin vast amounts of silver, drove its price even lower yet drew more miners to Colorado, which gained statehood in 1876.

Some 250 miles south of Denver, on the Old Spanish Trail between Santa Fe and Los Angeles, the Rio Grande meanders between green peaks bordering grasslands where Kit Carson’s nephew-in-law Tom Boggs ran cattle as early as the 1840s. By 1889 the town of Del Norte had become a base camp for miners, hunters and fishermen venturing northwest through Wagon Wheel Gap, gateway to the dark, winding world of the San Juan Mountains. Eight miles beyond the gap, at the bottom of remote Willow Creek Canyon, stood a cluster of miners’ tents with no roads, buildings or stores. Wagons climbed the 37 miles from Del Norte to bring in supplies.

By the end of 1891 the population of the little camp on Willow Creek had leaped from several hundred to more than 10,000 souls, most crammed between the towering canyon walls in a pocket just six-tenths of a square mile in area

For about a year after Nick Creede’s “Holy Moses!” lunch little changed in Willow Creek Canyon, except that he and George Smith dug a shaft and extracted ore samples with dazzling assay results. They finally took it all to David H. Moffat, wealthy president of the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad, who jumped at the chance to invest in the mine. The company tracks already stretched to Wagon Wheel Gap, so Moffat proposed building a spur to the canyon in order to haul out his ore. To his surprise the company’s other executives refused to back the plan. Determined to make the most of his new investment, the intrepid Moffat ultimately resigned from the railroad, financed the spur himself, then let the Denver & Rio Grande operate it in exchange for free shipping. Once he’d recouped the construction cost and turned a nice profit, he signed over the spur to the railroad.

Trains opened the human floodgates, and by the end of 1891 the population of the little camp on Willow Creek had leaped from several hundred to more than 10,000 souls, most crammed between the towering canyon walls in a pocket just six-tenths of a square mile in area. It was a town of businesses, with virtually no residential houses, which rapidly became a sea, or perhaps more properly a swamp, of humanity. The mud—a mix of dirt, rain, floodwaters, mine runoff and animal waste—was often knee-deep. As little sunlight reached the canyon floor, it never dried out, and nonstop traffic continually churned the muck. There were so many people, animals and wagons coming and going, it was hard to move. There was no incorporated town, so each corner of the canyon got its own name, taken from the nearest, biggest claim. Adjoining the original Holy Moses were Stringtown, Amethyst, Spar City, Stumptown and Weaver. At the busy heart of it all was Jimtown, while spilling out into the flatland was Bachelor, a makeshift suburban settlement for those working in town. Residents commonly referred to the whole muddy mess as Creede.

About the time Creede was on the make, Denver’s Law and Order League was cleaning up a criminal element that had taken over the city’s booze trade, gambling, prostitution and even politics. Jefferson Randolph “Soapy” Smith II, who earned his nickname running the notorious prize soap con (selling bars of soap in paper wrappers for $1 on the false promise some contained bills up to $100), had risen to run the Denver syndicate. A conspicuous philanthropist, he also had a piece of all the vice and graft in town, and he paid the police and city fathers to ensure he kept it. “The city is absolutely under the control of this prince of knaves,” the reform-minded Rocky Mountain News wrote about Smith, “and there is not a confidence man, a sneak thief or any other parasite upon the public who does not pursue his avocation under license from the man.”

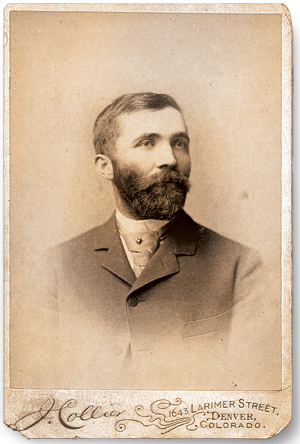

The Denver cleanup effort hinged on the mayoral election of 1889. The criminal element had a lot to lose if the Law and Order League candidate won, while a victory by the incumbent meant business would continue to flourish for the crime bosses. One of the key players in the syndicate was William Barclay “Bat” Masterson, who ran the gambling operations. Bat was a Renaissance man, an educated fine dresser with gentile manners, oiled black hair and a carefully styled mustache, who at times had been a buffalo hunter, Army scout, Indian fighter, boxing promoter, county sheriff and city marshal. He ran in big circles from New York to San Francisco, counting lawman Wyatt Earp and gunfighter Luke Short among his friends. On election day Bat, Soapy and their cronies walked the streets from one precinct to another, handing out slips of paper bearing dead men’s names and paying voters with cash and beer to use those names to vote multiple times. Regardless, their man lost, and syndicate control dwindled over the next couple of years, so Soapy, Bat and friends set their sights on the next boomtown, Creede.

They arrived late to the game, in February 1892, but were quick to establish a new syndicate, infusing Creede with their system of thugs, protection, kickbacks and political fixes. Prostitutes who accompanied Soapy from Denver helped him snap up deeds and leases until he owned most of Jimtown’s Main Street. Meanwhile, Bat managed the Denver Exchange, a saloon financed by a Denver investment group, and married his longtime girlfriend, Emma Moulton. The hardly blushing bride had finalized her divorce from her previous husband days earlier.

Two ore trains rolled out of Creede each day, each returning loaded with dozens more miners, storekeepers, opportunists and hangers-on. They spent freely in the town’s three-dozen-plus restaurants, 40-odd saloons, gambling halls and brothels. Creede also boasted two dentists, four doctors, three groceries, five general stores, six hardware stores, 10 livery stables, three printers and five assayers. In a boomtown almost entirely composed of businesses, everyone not working underground was competing to strip miners of their pay. Businesses filled the canyon floor, backed up against the basalt walls and even hovered on stilts over Willow Creek. Some operated out of tents, but most were in hastily erected frame buildings made of green wood sure to dry, shrink and crack within months. There was not a single brick structure, and the only paint showing on most places was on the sign. The busy railroad couldn’t keep up with maintenance, so disabled boxcars cluttered the sidings, one serving as Creede’s depot and telegraph office.

The place buzzed with so much excitement and so many dreams of the next mother lode, few gave much thought to rest. Anyway, Creede offered only enough hotel and boardinghouse rooms for about a third of its residents. The Denver & Rio Grande took to leaving sleeping cars on the sidetrack and charging weary townsmen a dollar a visit for their use. The miners slept in shifts, one flopping down exhausted on a warm bed as another rose to head for the mines or saloons. Some 2,000 at a time remained awake all night under the glow of new hydroelectric-powered streetlamps. Journalist Cy Warman, who left Denver in 1892 to launch his own newspaper, The Creede Chronicle, immortalized the city’s hardscrabble, sleepless existence in the closing verses of his poem “Creede”:

While the world is filled with sorrow,

And hearts must break and bleed—

It’s day all day in the daytime,

And there is no night in Creede.

Creede’s saloons and gambling halls typically occupied two-story buildings with false fronts, the bar running along one wall, leaving plenty of room for gaming tables. Some included a dance hall with a stage, separated from the gaming tables by swinging doors. Dark stairways led up to the rooms of soiled doves with such colorful monikers as Creede Lil, Killarney Kate, Slanting Annie and Timberline Rose. Bob Ford, the man who assassinated Jesse James, arrived to operate a saloon, with girlfriend Dot Evans running its upstairs brothel and notorious female gambler “Poker Alice” Tubbs dealing cards. Alice usually had a big black cigar in her mouth and openly packed a .38 Smith & Wesson. The impressible “Calamity Jane” Canary—whose acquaintance (a sweetheart in mind alone) “Wild Bill” Hickok had been murdered in Deadwood in 1876—was another rumored resident. By 1892 Calamity was a dedicated alcoholic in her 40s and had settled down with her husband and daughter to run a hotel in Boulder. But legend has it she boarded at Zang’s Hotel in Creede for a time, possibly seeking adventure or perhaps backsliding into prostitution.

The miners who laid down their bets and bedded the soiled doves were far from the stereotypical weary sourdough leading his swaybacked burro on an endless circuit of the West. Most were company men. Under the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, with the price of ore low and demand sky-high, the only way to make silver mining pay was to produce huge quantities of ore. So virtually every time a prospector struck silver, he sold his claim to a mining company, which then brought in engineers and the latest machinery and hired on men as diggers. As the mines drove ever deeper, they filled with water, calling for tunneling companies, which employed even more men and machines to drain the shafts. After a time virtually all miners in Creede were employees clocking 12-hour shifts for round-the-clock mining operations.

While they toiled day after repetitive, dust-choked day, Soapy, Bat, Ford and other entrepreneurs took a piece of every dollar in town and never had to get their hands dirty. The syndicate disliked Ford, as his tavern became a den of violence. He had a way of antagonizing customers, men such as Edward O’Kelley, an alcoholic who, like Ford, hailed from Missouri. An admirer of Jesse James—thus almost certainly holding a grudge against his assassin—O’Kelley became marshal of Bachelor in March 1892. In April he reportedly received a beating in Ford’s saloon.

Many such men measured their explosive life in Creede in months, others only weeks. Faro dealer William “Reddy” McCann was among the many gamblers who had arrived from Denver that February. Around 4 a.m. on March 31 a drunken McCann shot out a dozen of the new streetlights on Main, then dropped into the Branch Saloon for a drink and a cigar. Minutes later William “Cap” Light, Soapy’s brother-in-law, strolled in. Light—who’d served as a deputy sheriff in Temple, Texas, then an enforcer for the Denver syndicate—was Soapy’s new deputy in Jimtown. Though he lacked a badge, he was fearless and forceful, which townspeople seemed to agree was what Creede needed at the time.

Light informed McCann he was under arrest for shooting up the town. When McCann brushed him off and insisted on finishing his drink, the short-tempered Light slapped the cigar from his mouth. Pushing away from the bar, McCann drew his revolver from its holster. Light wasn’t daunted, having faced down gunmen and killed two of them as a lawman in Texas. As the drunken McCann snapped off two wild shots, Light pulled his pistol, took deliberate aim and fired three times. Hit by all three slugs, McCann fell, moaning, “I’m killed”—and he was right.

Such episodes were surprisingly rare. Most Creedites favored strong law enforcement, and what the town lacked in such stabilizing influences as churches, families and a regular city government it made up for with an understanding the syndicate wasn’t going to abide either reckless gunplay or gunfights. And considering the number of people living atop one another in Willow Creek Canyon, the amount of money they all made and lost, and the abundance of vices available to them, the place remained relatively free of violent crime. A stern talking-to from a Creede policeman, a night in the slammer or at worst a pistol butt across the noggin was all it took to keep most men in line, and it all operated at the pleasure of the syndicate. Miners were expected to behave and spend their money, and business operators were expected to make money. The more one made, the more everyone benefited.

The syndicate duly chastised the impulsive Light for killing McCann, and the downcast deputy, recognizing that his brand of law enforcement was becoming an anachronism, returned to Texas. Relative peace returned to Creede, as workmen replaced the streetlights McCann had shot out. Less than three weeks later someone shot them out again.

The night of April 17 Bat Masterson set up a match between Billy Woods, a black heavyweight boxer who had made a lot of money for Masterson in Denver, against local tough Al Johnson. The betting was heavy in Creede, with Johnson the decided favorite. Masterson made sure everything about the match was first-class, with an elevated ring in the middle of Main Street, Marquess of Queensbury rules, a professional referee and a sizable purse.

Saloonkeeper Ford was in attendance, liquored-up and letting his money ride on Johnson. He also may have been on edge, as April 3 had marked 10 years to the day he shot James in the back of the head, and he feared a similar fate. So when Billy Woods won the fight, losing Ford a lot of money, the sloshed saloonkeeper pulled his pistol and shot at the stars. Then he reloaded and shot at streetlights, windows, signs and water barrels. Deputies on hand simply waited until Ford wearied of shooting, quietly arrested him and put him on a train out of town. Only after he begged Soapy for forgiveness and promised to behave was he allowed to return a few days later. Eager to comply with the syndicate’s entrepreneurial credo, he soon found an investor and opened a new saloon, Ford’s Exchange, with the brightest paint job in town.

In the early morning hours of Sunday, June 5, everything the townspeople had worked for went up in flames. The blaze began in a saloon, and before the volunteer fire department could make their way through the thousands of curious onlookers and horses clogging the streets, the flames had sped from one frame building to the next. Noting with alarm that the town’s liquor supply was also going up in flames, quick-thinking schemers did manage to tote cases of whiskey and roll barrels of beer to safety, providing refreshment to spectators taking in the fire. Only after the unchecked blaze had ravaged the business district did it burn itself out at the base of the gorge.

The debris couldn’t be cleared until the ashes cooled, but impatient Creedites weren’t about to wait for that. Telegrams brought trains with beer, whiskey and tents the next morning, and within 24 hours virtually the entire business district reopened as a sea of white canvas on wooden platforms. Bob Ford, whose brightly painted Exchange saloon was among the buildings lost to the fire, reopened in a tent. He was standing at the bar on the afternoon of June 8 when a drunken Ed O’Kelley walked in, called out, “Hello, Bob,” and triggered both barrels of a shotgun, shredding Ford’s neck with buckshot and killing him instantly. Less than a week later Creede incorporated, and a month later residents elected a mayor and aldermen. By month’s end O’Kelley had been sentenced to life in prison for murder, though he’d serve only nine years before his release.

Just over a year later, as financial markets went into free fall during the Panic of 1893, Congress repealed the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, prefacing a return to the gold standard of exchange. Silver prices were already at rock bottom, so when the government stopped buying silver, the big mines were ruined, and almost everyone in town moved on in search of better stakes. Original settler Nick Creede, made fabulously wealthy from his shares in Creede’s mines, had already moved on to Pueblo, Colo., and then Los Angeles, along the way getting married and adopting a daughter. Alas, in 1897 the marriage ended in divorce, and Creede died soon after from an accidental overdose of morphine, leaving the bulk of his estate to his adopted daughter. In the town that bore his name timeless canyon winds whistled through the weathered slats of decaying buildings on every street. The flash in the pan was over. In 2010, according to the U.S. census, the town population was 290. WW