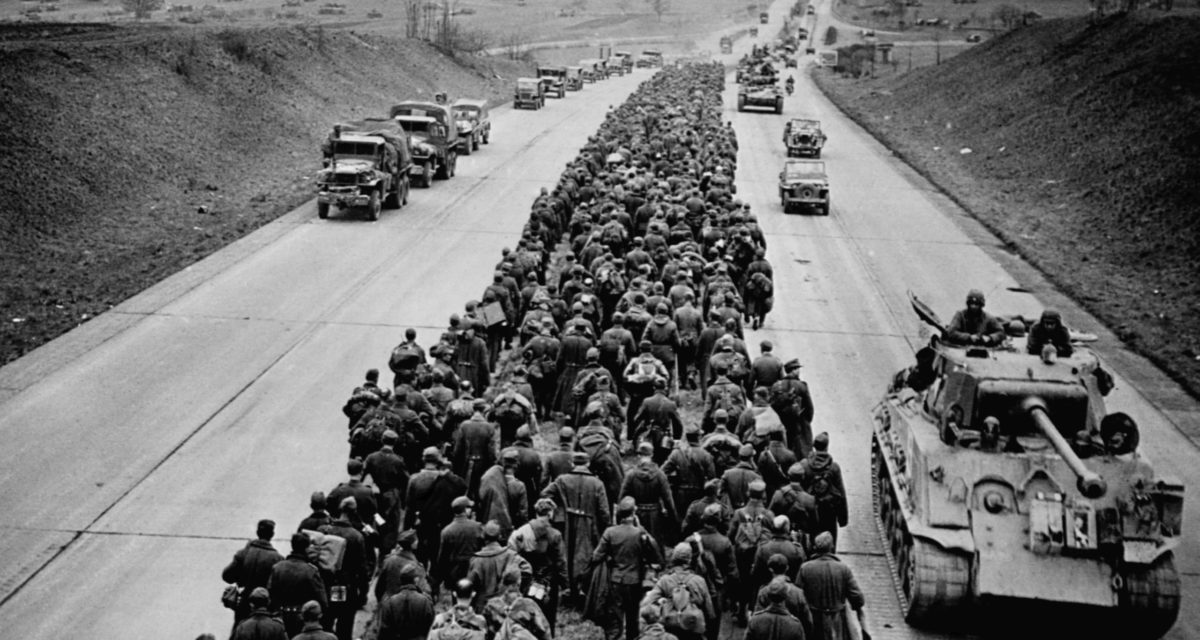

Compressed by the popular imagination into a head-on charge to victory, the dozen weeks of fighting that put paid to the Thousand-Year Reich constituted a complex and highly engineered, yet brutal and often improvised end game. The conflict’s outcome was not in doubt — though in the lees of the Ardennes counterattack a rueful Gen. George Patton wrote in his diary entry for Jan. 4, 1945, “We can still lose this war.”— but the cost of and paths to triumph were. In titling his latest effort “Fire and Steel: The End of World War II in the West,” the talented and prolific military historian Peter Caddick-Adams reprises the trope he coined in naming volumes on the Battle of the Bulge (2014’s “Snow and Steel”) and the Allied invasion at Normandy (2019’s “Sand and Steel”). Caddick-Adams as easily could have played on the subtitle of his 2013 account of the arduous reduction of the Wehrmacht redoubt at Monte Cassino (2013’s “Ten Armies in Hell”) to characterize the hard, gruesome work seven Allied armies had to undertake to liberate the last of Europe, including Germany itself, from obstinate Hitlerian control.

These liberating armies, too, spent a season in hell: the American 1st, 3rd, 7th, and 9th; the British 2nd; the Canadian 1st; and the French 1st. The author properly dives into and sorts the disputations that inevitably arose within and among the leadership and subordinate elements of this fractious assemblage as its millions of warriors rumbled across the Continent. Not all the fighting in the ETO involved enemy troops, and “Fire and Steel” illuminates these internecine arguments and their effects on making war.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

For good reason Caddick-Adams uses the 820-mile Rhine River, Europe’s greatest waterway and defensive perimeter, to frame “Fire and Steel.” He gives the river pride of place, dividing his narrative into sections slugged “To the Rhine,” “Across the Rhine,” and “Beyond the Rhine.” Until the liberating armies could secure a lodgment on the great stream’s east bank sufficient to mount a drive to Berlin, they might as well have been sitting on Omaha Beach playing pinochle. Hence Caddick-Adams’s strategic decision to devote 80 of his book’s 529 pages to the intricacies of the attackers’ approach to, the unlikely survival of, and the fleeting but crucial service provided the Allies by the bridges over the Rhine at Remagen.

Another of the author’s strategic decisions is to visit and repeatedly revisit in excruciating detail the serial awakening among advancing Allied troops to the systematic horrors of the German death camps. As his countryman Richard Overby does effectively but statistically in his recent “Blood and Ruins: The Last Imperial War 1931-1945,” Caddick-Adams, presenting visceral first-glimpse recollections by individual soldiers, reminds the reader that Nazi Germany was a gangster state whose economy ran on slavery.

Fluent in high-altitude analysis, Caddick-Adams spices that needed sense of historical remove with judicious cuts to close-ups of men at arms in deep duress of many sorts. “Fire and Steel” page by page replaces glib assumptions about the final sequence of events that brought Germany’s totter and fall with a rich and emotionally wringing grasp of what that achievement really took.

Michael Dolan was senior editor of World War II magazine from 2012 to 2016.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.