Resistance isn’t always glorious in real life, nor in Jean-Pierre Melville’s Army of Shadows.

In September 1984 I was a wide-eyed American student on my first trip to Europe, there to pursue my master’s degree at King’s College London. The Cold War was then at a renewed height, and many Europeans pointed fingers of blame at President Ronald Reagan, whose firm military stance against the Soviets and rhetoric of their “evil empire” seemed inadvertently—or perhaps intentionally—liable to provoke a full-scale conflict between NATO nations and Soviet-backed Warsaw Pact countries.

Nor was that all. I had no sooner made my home in an international residence hall than a movie debuted on Leicester Square that was widely viewed as sheer American jingoistic propaganda. The film was Red Dawn, a preposterous concoction in which the entire Communist world—Soviets, Cubans, Nicaraguans, East Germans—executes a surprise invasion of the United States. The contours of the war are left vague in all ways but one: deep in the Colorado Rockies, a young band of American students—dubbed the “Wolverines” after their high school mascot—conduct a flamboyantly effective resistance movement against the Communist occupiers. Watching this premise unfold on the silver screen and reflecting on its solid box office success one critic reflected, “You understand better now why the most important person in the United States has begun dreaming aloud of bombing the ‘empire of evil.’” In short, the film seemed an adolescent fantasy.

But for me, Red Dawn was less a source of alarm or offense than of acute embarrassment. There was something surpassingly tasteless about the American imagining of an experience—military occupation—that millions of Europeans had endured within living memory. True, like the fictional Wolverines, some Europeans had also resisted. But the reality of their resistance bore little resemblance to the lurid Hollywood invention.

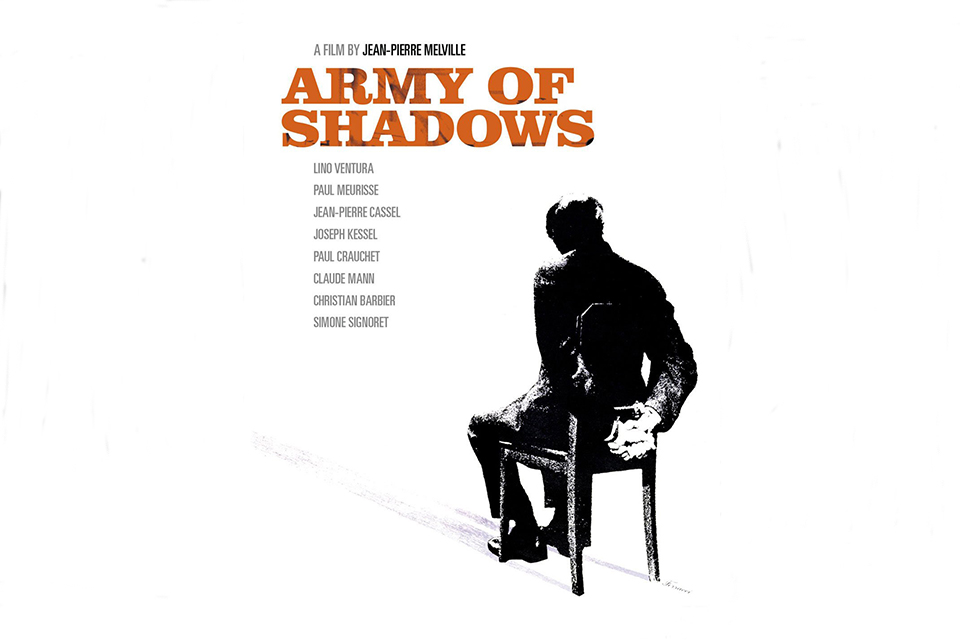

Perhaps no film drives home that point more strongly than L’Armée des Ombres (Army of Shadows), a 1969 epic written and directed by Jean-Pierre Melville, who had himself been a member of the French Resistance against the Nazis. And not just the Nazis; resistance also required opposition to one’s own government, the state of Vichy France, which the victorious Germans had established as a puppet regime. Indeed, the movie opens in unoccupied France—the Free Zone—where Vichy authorities have imprisoned the film’s main protagonist, Philippe Gerbier (Lino Ventura), a self-possessed industrial engineer in his early 40s who looks nothing like a man of action or derring-do. How Gerbier became involved in the Resistance is not defined. What soon becomes clear, however, is that he is part of a loose confederation of courageous individuals, many of whom have only the sketchiest knowledge of the others.

The film depicts no dramatic raids on enemy warehouses or troop trains; in fact, there isn’t a single scene reminiscent of Red Dawn. Gerbier and his compatriots are mainly concerned just with surviving long enough to do the slow work of organizing a large-scale resistance—a task that, judging by their limited results, may well be a fool’s errand. What drives them onward appears to be more simple faith—a need to do right for its own sake—rather than hope of victory.

Its director, however, never romanticizes doing right by cloaking it as something noble. For example, after Vichy authorities hand Gerbier over to the Germans and he manages to escape, he and three colleagues find it necessary to execute a frail, frightened young man who, it transpires, was the one who betrayed Gerbier in the first place. One team member has rented a seemingly secluded house in which they expect to neatly dispatch the youth with a pistol, only to discover last minute that its previously vacant units are occupied and a pistol is now out of the question; the loud gunshot will give them away at once. The only viable method, they conclude, is to twist a towel around the victim’s neck and choke him to death. The deed may be just and imperative, but its perpetrators experience it only as loathsome and ugly. When it is finished, a shaken teammate confesses to Gerbier, “I did not think we could do it.”

“Neither did I,” Gerbier responds.

Later events take an even greater spiritual toll—including the pitiless assassination of a courageous female resister who has been compromised to the Germans and thus becomes an innocent but intolerable threat; she simply knows too much. And in a sense the whole drama comes to naught, for the film’s conclusion makes clear that all of the major protagonists—Gerbier included—encounter imprisonment, torture, and death long before they have a prayer of witnessing the hour of liberation. But Army of Shadows is not about the triumph of resistance. It is about its cost: not just to the body, but to the soul. In war, doing right and feeling right have little to do with each other. ✯

This article was published in the April 2020 issue of World War II.