Two empty freight train cars fell into the Potomac River, closing sites including John Brown’s Fort and The Point

Seven empty northbound freight cars jumped the rails on a Potomac River bridge in the Harpers Ferry National Historical Park last month, wiping out a popular pedestrian bridge that serves both visitors to the park and the hikers on the Appalachian Trail.

CSX Transportation officials said no one was injured in the derailment, which happened in the early hours of Saturday morning Dec. 21. No cause was announced, and the 125-year-old bridge—built by the old B&O Railroad—reopened to train traffic two days after the incident.

Two of the cars landed in the Potomac, not far from the fire engine house that served as a fort for abolitionist John Brown’s raiders in 1859. The cars were used to haul grain and did not contain any dangerous substances, CSX officials said.

The derailment closed sites at Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, including John Brown’s Fort and The Point. Getting the worst of it was the pedestrian bridge cantilevered to the railroad bridge, which is a vital link in the Appalachian Trail. No timetable has been set for its reopening or the other parts of the park.

Along with the Appalachian Trail, the bridge links the Harpers Ferry National Historical Park on the West Virginia side of the Potomac with the Chesapeake and Ohio National Historical Park. It’s a rare place where three National Park units converge.

Hikers and bicyclists on the C&O towpath use the bridge to visit Harpers Ferry, and visitors to Harpers Ferry use the bridge to access the trail to Maryland Heights for an iconic view of the town. Maryland Heights played a key role in Lt. Gen. Stonewall Jackson’s capture of Harpers Ferry and more than 12,000 Union soldiers in 1862 in a prelude the Battle of Antietam.

Harpers Ferry Mayor Wayne Bishop told MetroNews of West Virginia that he hopes CSX shows the “same enthusiasm” for repairing the pedestrian bridge as it did for reopening the bridge to freight traffic.

Looking Their Best

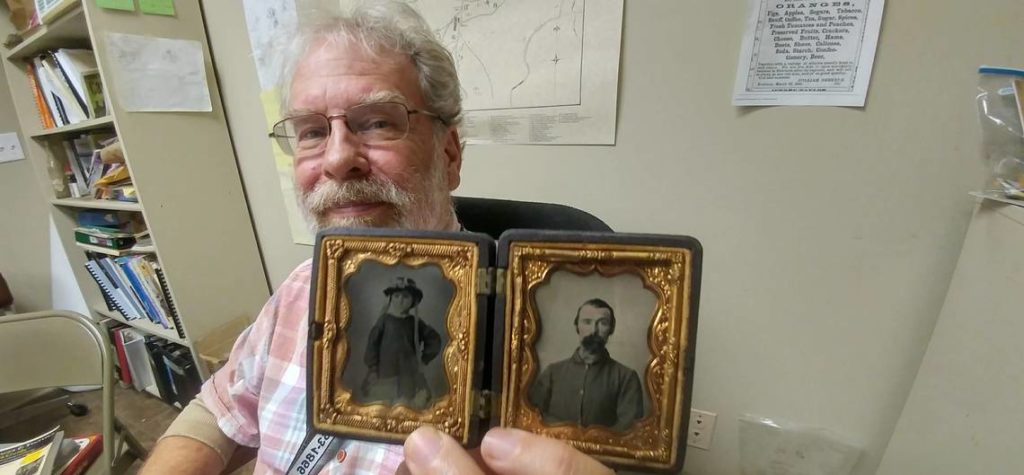

Soldiers on both sides of the Civil War had ready access to a form of immortality soldiers earlier generations could not have dreamed of: photographic portraits to record their images for posterity.

ew technologies made both ambrotype (glass-backed) and tintype (metal-backed) emulsion plates affordable for the average Civil War soldier, and thousands had their personal portraits made. And, much as people today spiff up to have their photos taken, the soldiers wanted to look their best, even to the extent of dyeing their hair to appear younger and more vigorous.

When archaeologists from Transylvania University working at Camp Nelson—a former Union supply depot in central Kentucky—unearthed broken bottles at the site of a photography studio on the excavation site, they initially thought the bottles had likely contained medicine. Further research, however, indicated the bottles actually contained hair dyes used to darken light-toned locks, products that went by names such as “Christadoro” and “Dr. Jaynes.”

But it wasn’t just older, graying men who used the product.

“One of the things the photographic books mention is if you had light-colored or blonde hair, the black and white photography process could make you look like you had white hair or gray hair,” researcher Stephen McBride told Newsweek.

Founded in 1863, Camp Nelson eventually covered more than 4,000 acres, with more than 300 buildings and tents, and housed 8,000 or so soldiers. A range of private businesses, including the photography studio, were allowed to set up shop, leading to a treasure trove for researchers today.

“Civil War photographic discovery is still very active today,” Bob Zeller, director of the Center for Civil War Photography, told the Lexington (Ky.) Herald-Leader.

“And now we have an archaeological discovery of a Civil War photo studio. As far as I know, it has not happened before.”

Manassas Burns Again

Smoke rose once again from the Civil War battlefield in Manassas, Va., in late November, but this time it was for a more benign reason than when the First and Second Battles of Manassas (Bull Run) were fought there in July 1861 and August 1862, respectively.

Instead of using mowers to maintain the battlefields, keeping them free of brush and trees, the National Park Service conducted a controlled burn on 75 acres near Brawner Farm, to restore the landscape to its 1860s appearance. An added benefit of the fire is the reduction of invasive plant species in natural grasslands that are home to ground-nesting birds, like bobwhite quail. Controlled burning is cheaper and more effective than using equipment to maintain the battlefield, officials said. This was the third time that controlled burns had been conducted at the battlefield.

“Building off the great success we had with prescribed fires in April 2018 and March 2019, this is another opportunity to continue our efforts to return a significant segment of the battlefield back to its Civil War appearance,” Manassas National Battlefield Park Superintendent Brandon Bies said. “In addition to supporting the park’s goal of landscape restoration, prescribed fire allows native grasses to flourish and improves wildlife habitat.”

The long-term benefits of the burns outweigh any short-term impact from the smoke, Bies said, and safety is always a top priority.

Cutting Edge

In a fascinating application of today’s cutting-edge technology to 1860s cutting-edge technology, modern artificial intelligence is putting names to photos of previously unidentified Civil War soldiers.

Kurt Luther, professor of history and computer science at Virginia Tech, founded Civil War Photo Sleuth in 2018, which uses facial recognition technology to identify soldiers whose names had been lost to history.

The technology analyzes 27 facial landmarks, such as the corners of the mouth or the tip of the nose, and then hunts for a match in a database of nearly 30,000 photographic images uploaded to the Photo Sleuth site from various contributors. Luther’s partners are Ron Coddington, editor and publisher of Military Images Magazine, and professor Paul Quigley, director of the Virginia Center for Civil War Studies. The service is free.

To date, Civil War Photo Sleuth has made more than 3,300 identifications with an accuracy rate estimated between 75 percent and 80 percent, according to Luther and his team. The site has 14,000 registered users, including employees at the Library of Congress and the National Archives, as well as private collectors.

More information about Civil War Photo Sleuth is available at civilwarphotosleuth.com.

Best and Worst of Civil War Films

In what is sure to provide grist for passionate discussion, the movie review website Rotten Tomatoes identified the five best and five worst movies set during the Civil War. The rankings are based on reviews by writers who are certified members of various writing guilds or film critic associations.

In the rankings below, percentages indicate positive reviews.

Best

The Good, The Bad and The Ugly (1966)—97%

Glory (1989)±93%

The General (1927)—92%

Lincoln (2012)—89%

Dances With Wolves (1990)—82%

Worst

Gods and Generals (2003)±8%

Jonah Hex (2010)—12%

Field of Lost Shoes (2014)—39%

Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter (2012)—34%

Free State of Jones (2016)—46%