[dropcap]T[/dropcap]hose planes were over our community,” scolded the enraged man with three stars on each shoulder. “They were enemy planes. I mean Japanese planes.”

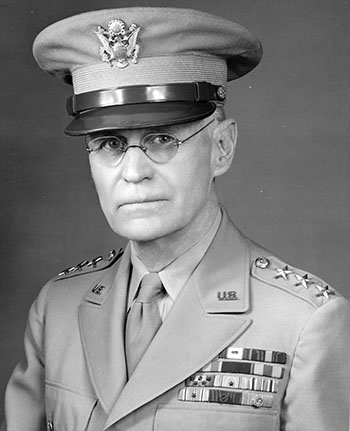

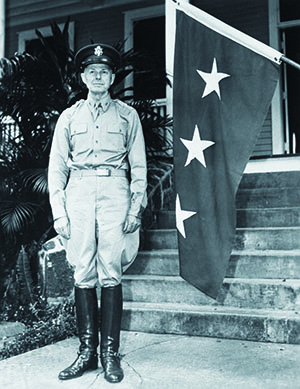

It was the morning of December 9, 1941, and Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt had come to San Francisco’s City Hall to address an emergency meeting of the city’s Civil Defense Council. The city’s top civilian leaders were there, including Mayor Angelo Rossi and his department heads, but DeWitt was the man of the hour. He stood before them, tall and erect, with a physique like that of a steel scarecrow. Stern and bespectacled, he glowered at the city fathers with the eyes of an uncompromising schoolmaster about to rake errant students across the coals of his wrath.

Just shy of his 62nd birthday, DeWitt had been in uniform for nearly 44 years but, having been born and raised on army posts, considered himself to have been in the army all his life. From his headquarters in the 1,500-acre Presidio of San Francisco—a U.S. Army fort near the Golden Gate Bridge, now a part of the National Park Service—he led the Western Defense Command and the U.S. Fourth Army. One of the army’s handful of three-star generals, DeWitt was the senior commander in the West: the man responsible for the defense of the 1,300-mile coastline of the three Pacific coast states and the more-than 6,000-mile coastline of the Territory of Alaska.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor just 48 hours earlier had shocked and galvanized the nation—but on the West Coast, people were reacting with special trepidation. Until sunrise on that terrible Sunday, air attacks by enemy bombers were something that happened only on the other side of the world. Suddenly, the havoc people had seen in newsreels of the London Blitz no longer seemed so abstract. By Tuesday, most people assumed that it was possible—indeed probable—that an enemy who could rain destruction halfway across the Pacific could reach all the way to the West Coast and rain destruction upon cities from Seattle to San Diego.

On the evening of December 8, DeWitt had ordered a blackout of San Francisco to prevent the city lights from aiding navigators of presumed incoming enemy bombers. But large swaths of the city had remained illuminated.

DeWitt was livid.

“Death and destruction are likely to come to this city at any moment,” he asserted to the city leaders, while a United Press correspondent took notes. “Unless definite and stern action is taken to correct last night’s deficiencies, a great deal of destruction will come.”

As with Winston Churchill a year and a half earlier during the Battle of Britain, DeWitt had been handed an opportunity to set the tone that would carry his people through a time of grave crisis. “I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears, and sweat,” the British prime minister had told his people.

But where Churchill’s words were inspirational, DeWitt’s were disconcerting at best. Churchill had stood with his people to lead them through a maelstrom of darkness and adversity. DeWitt, on the other hand, accused his people of “criminal apathy.” Interpreting the city’s failure to achieve a complete blackout as a dereliction of duty rather than a clumsy beginning on a steep learning curve, he screamed at San Francisco’s civilian leaders, telling them their city contained “more damned fools…than I have ever seen.” The Japanese were out there and they were coming, DeWitt angrily told city officials. “If I can’t knock these facts into your heads with words, I will have to turn you over to the police and let them knock them into you with clubs.”

There was fear behind DeWitt’s tough talk. But while he spoke of Japanese bombers and fanned the public’s concern over enemy saboteurs already inflaming street corners and editorial pages across the West, at the heart of his fear was the dread of sharing the fate of his old friend and colleague, Lieutenant General Walter C. Short.

The army’s senior commander in Hawaii, Short was relieved of duty on December 17, 1941, for having his forces “not on the alert.” Like DeWitt, Short had methodically climbed the career ladder. Now the general’s career and reputation were in shambles. En route to Washington a few days after losing his command, Short stopped off in San Francisco, where he called on DeWitt at the Presidio. Joining them was Short’s aide-de-camp, Captain Louis W. Truman, a second cousin to then-senator Harry S. Truman. “Short had taken off one star [indicating that relief in command resulted in Short reverting from a temporary rank to his permanent two-star rank of major general],” Louis Truman recalled decades later. “And so DeWitt asked him, ‘Walter, what can I do to protect myself here?’… I heard Short say, ‘Well, be damn sure you know what the War Department is telling you.’”

In a 1991 oral history interview by Neil Johnson of the Truman Presidential Library, Louis Truman went on to say that Short had counseled vigilance, telling DeWitt to carefully consider what was expected of him and noting the scant guidance Short and his naval counterpart, Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, had gotten from the War Department and navy officials about Washington’s expectations ahead of the Pearl Harbor attack.

Colonel Victor Hansen, a member of DeWitt’s War Plans Division and later a respected California superior court judge, remembered that DeWitt greatly feared the wrath of the leaders who had fired Short: Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson and army chief of staff General George C. Marshall. “I’m charged with the protection of the West Coast,” Hansen recalls DeWitt saying on multiple occasions: “Not only the defense of the coast, but I’m in charge of the whole defense. I’m on notice of this.”

DEWITT VERY MUCH UNDERSTOOD what it meant to be “on notice” and, benefiting from Short’s experience, intended to ensure this reality would guide his actions.

His actions, however, raise a host of questions.

Did DeWitt truly believe that there were Japanese planes over the West Coast? Perhaps, though he should have known better. Some of the “sightings” of Japanese planes in the early months of the war were attributable to American aircraft, but many reports arose when there was nothing for military or civilian spotters to see or hear. Regardless of the sights and sounds of unidentified airplanes, or the absence thereof, the complete lack of hard evidence—bombs being dropped, for example—should have provided a clue that there was no enemy in the sky.

Did DeWitt truly believe there were saboteurs lurking beneath every strategic bridge, or spies signaling to enemy submarines offshore? Quite possibly. “DeWitt took every report most seriously,” writes historian H. W. Brands in his book about Franklin D. Roosevelt, Traitor to His Class. In DeWitt’s mind, “Stray radio signals became secret transmissions from Japanese spies to ships offshore. When the signals fell silent, their very silence indicated the insidious guile of the enemy.”

Or was DeWitt covering up for the inadequacies of his own command? At least in the beginning, there were reasons for concern about the ability of his first responders to respond. In a press conference the same day as DeWitt’s tirade at San Francisco’s City Hall, Brigadier General William Ord Ryan, commander of the IV Interceptor Command, confirmed DeWitt’s assertions of Japanese aircraft over the city.

“There was an actual attack,” said Ryan, whose handful of fighter planes, scattered at airfields across the West, were the first line of defense against any air attack. “A strong squadron was detected approaching the Golden Gate. It was not an air raid test. It was the real thing. The planes came from the sea and turned back.”

When a reporter asked whether Ryan’s interceptors had gone up to meet the intruders, he replied that “you don’t send planes up unless you know what the enemy is doing and where they are going. And you don’t send planes up in the dark unless you know what you are doing.”

Ryan’s admission that the IV Interceptor Command knew neither what the enemy was doing—aside from apparently flying over the West’s second largest city—nor what his own command was doing, did little to allay public concerns. Again and again Ryan kept his planes grounded, notably on the night of February 24-25, 1942, when “mystery airplanes” over Los Angeles were met with 1,400 rounds from antiaircraft guns—but no interceptors.

Today, we know that no Japanese aircraft carrier ever ventured close enough to the West Coast to attack San Francisco, Los Angeles, or other cities on the numerous nights when DeWitt or someone in his chain of command declared a blackout. Nor did the Japanese have any secret airfields in Mexico, as had been widely rumored in 1941-42.

The Japanese did conduct a submarine campaign off the West Coast for most of December 1941 that resulted in the loss of two American merchant ships—including one that sank in dramatic fashion in full view of the Pacific Coast Highway. In early 1942 enemy subs returned to shell two targets on land and to sink another ship near the mouth of Alaska’s Puget Sound. While the state-of-the-art Japanese B1-class submarines that took part in these operations had hangars on deck that could each accommodate a single observation plane, those hangars most often carried extra fuel for the submarines.

The only confirmed attacks by Japanese aircraft on the West Coast were two bombing strikes in September 1942 against the forests of southwestern Oregon by a floatplane launched from the submarine I-25. Warrant Officer Nobuo Fujita managed to drop two incendiary bombs during each strike, but the forest fires he aimed to ignite fizzled among the damp, fog-soaked cedars.

JOHN L. DEWITT was a man ill-suited for the post he held. His appointment to this assignment had probably looked good on paper in 1939, but he was an administrator, not a combat commander. DeWitt was a product of an insular bureaucracy, having worked his way up the rungs. His specialty had been logistics. In World War I he had been the supply officer for the First Army; his most prominent position before his present post had been as the army’s quartermaster general. Nevertheless, with his Western Defense Command designated as a theater of operations on December 11, 1941, this combat-inexperienced general now found himself a theater commander.

The power he wielded was, for a time, almost omnipotent. On December 13, 1941, the morning after another false-alarm blackout—spurred by a report of enemy bombers headed for Los Angeles—he had sent a memo to California Governor Culbert Olson ordering that the Pasadena Tournament of Roses Parade and the Rose Bowl football game, scheduled for New Year’s Day, be canceled “for reasons of national defense and civilian protection.”

As DeWitt told Victor Hansen of the War Plans Division that week, a situation like this, where many thousands of people gathered, would be an ideal time for saboteurs, who “are going to get in there and blow these people up, and you’re going to have to account for this.”

Tickets to the game, already two-thirds of the way to a sell-out, were, as the Los Angeles Times put it, “usually worth their weight in gold, and now only scrap paper.” Duke University, favored by 14, offered to host the game at their stadium in Durham, North Carolina. It would turn out to be Oregon State’s only Rose Bowl victory.

DeWitt’s assertions about unseen saboteurs helped stoke the already widespread public panic. Anxious constituents pressured state officials and congressmen for action. In the Senate, Monrad “Mon” Wallgren, a Democrat from Washington, asked “that the War Department be given full and immediate power to clear all strategic areas of enemy aliens, ‘dual citizens,’ their families, and their children—even though the children may be U.S. citizens—and place them in internment camps.” John M. Costello, a Democrat from Southern California, told the House of Representatives that “if we don’t move in advance of…sabotage, Pearl Harbor will be insignificant to what will happen here. All of the Japanese should be moved out of the area for their own good as well as ours.”

The cry was heard at the White House, where the infamous Executive Order 9066 went to President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s desk for signature on February 19, 1942. It authorized the secretary of war to designate “military commanders” to “prescribe military areas…from which any or all persons may be excluded.”

The commander thus appointed was DeWitt, who prescribed the three Pacific coast states as the “military area,” and all Japanese Americans—never mind that two-thirds were American citizens—became the people to be “excluded.” This in turn led to the internment of as many as 120,000 people for the duration of the war—one of the worst injustices inflicted on Americans by their own leaders since the Civil War.

FOR A TIME, DeWitt remained omnipotent. “In a military way, he holds us all in the palm of his hand,” wrote Los Angeles Times columnist Tom Treanor in 1942, after interviewing DeWitt for his March 5 column. “His is the authority to do what the situation calls for in the Western theater. On his skill and judgment rests the efficiency of our defenses. He is the boss out here.”

DeWitt seemed to relish this role. His typical response to the news media was to reply to their questions with a disdainful “none of your business.” Treanor’s column described how DeWitt ordered him not to publish the substance of his interview: “General DeWitt said that when there is something to be told he will tell you himself. He seems accustomed to obedience, so the chances are I will obey him.”

DeWitt was the man whom state governors, never mind journalists, dared not disobey. When he said that Japanese aircraft were overhead—which he did sometimes several times a week in the early months after Pearl Harbor—the media and the general public believed him. For the better part of a year, they were—to borrow Treanor’s phrasing—inclined to trust the “skill and judgment” of “the boss.”

Gradually, however, the credibility of the boss’s skill and judgment lost its luster. The Japanese invasion of the Aleutian Islands of Attu and Kiska in June 1942 and the year-long occupation that followed made the theater commander seem impotent. Meanwhile, the narrative of Japanese American sabotage, which had seemed so probable in the days after Pearl Harbor, had begun to fray. No evidence of West Coast sabotage or subversion, nor conspiracies of any sort, materialized. By 1943, the pendulum of public opinion, especially across the rest of the country, began to swing in the opposite direction, bringing with it a strong tide of support for allowing Japanese Americans to return to their homes.

The turning point for DeWitt came in April 1943. Congressman and World War I Medal of Honor recipient Edouard Izac, a Democrat from California, arrived in San Francisco with members of the House Committee on Naval Affairs, which he chaired, for a series of hearings on defense matters. For the first time, the boss found himself on the defensive.

“A Jap’s a Jap,” DeWitt insisted when Izac asked him about the evolving public opinion on the matter of Japanese Americans. “It makes no difference whether he is an American citizen or not…. I don’t want any of them. We got them out. They were a dangerous element. The West Coast is too vital and too vulnerable to take any chances.”

Three days later, at 8:19 p.m. on Easter Sunday, DeWitt’s Western Defense Command issued a “yellow alert” warning, plunging Los Angeles into the darkness of a blackout. As had happened in the wake of all the other air raid warnings and chaotic blackouts since December, the “all-clear” sounded in the wee hours of the next morning and, in the clear light of day, an official spokesman in DeWitt’s chain of command confirmed that it was yet another false alarm.

Shortly thereafter, rumors began to circulate in Washington that the boss’s bosses had had enough. DeWitt was an embarrassment. Secretary of War Stimson and army chief of staff Marshall allowed him to remain in his post through the recapturing of Attu and Kiska by mid-August 1943, though he served only as a figurehead in the operation. When that was done, so, too, was DeWitt’s time on the Pacific coast.

DeWitt headed to Washington, D.C., to lead the newly created Army and Navy Staff College—a training program for officers destined for joint operations. There he found himself out of the limelight, his area of responsibility reduced from 1.2 million square miles to a suite of offices. DeWitt might have retired into obscurity from there, but his career took one more twist.

In August 1944, the Associated Press reported that DeWitt had been relocated to England, having been summoned to Europe to take up an “undisclosed command of great importance.” The mysterious assignment, not revealed until after the war, was to command the fictitious First U.S. Army Group (FUSAG). Before the Normandy invasion in June 1944, military leaders created FUSAG, under the command of Lieutenant General George S. Patton, as a part of a massive deception. The Allies leaked “secret” information to the Germans about an immense fighting force being prepared for a cross-Channel invasion in the vicinity of Calais. The Germans believed it and diverted a substantial force to meet it, thus watering down their defensive forces in Normandy.

Allied leaders decided to keep the ruse going. When Patton took command of Third Army after the invasion, commander of U.S. Army ground forces Lieutenant General Lesley J. McNair was moved out of Washington and reassigned to head FUSAG. But two days after arriving in France on July 23, McNair died in a friendly fire disaster. The War Department scrambled for a successor—a lieutenant general with little else to do. It settled on DeWitt.

From the command of much, to the command of very little, DeWitt’s new assignment was now to command nothing. Military leaders eventually terminated the imaginary FUSAG without fanfare and it went away virtually unnoticed. The man who had commanded it also faded into a corner of history, overshadowed by so many who had done so much to win the war.

DeWitt’s departure from the Presidio of San Francisco in 1943 had been front-page news. His final departure from the U.S. Army in 1947 went unnoticed by the press. He lived his final years at an apartment building in Washington, D.C., and died of a heart attack in 1962 at age 82. He is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

WHILE RECENTLY RESEARCHING a book about the Pacific coast during the war, I mentioned DeWitt’s name at the visitor center at the Presidio. I received blank stares. We were standing literally across a parking lot from DeWitt’s wartime headquarters, but no one on duty could recall having even heard his name. When I contacted the museum at Quartermaster Corps headquarters at Fort Lee, Virginia, where DeWitt served as the army’s quartermaster general, I learned that mine was one of a scant handful of inquiries they had received about DeWitt in more than three decades.

Except in the institutional memory of Japanese Americans, where his name is still spoken as an obscenity, the once formidable ruler of the Pacific coast is little more than a forgotten footnote to World War II, even in the land he once ruled. ✯

This story was originally published in the August 2017 issue of World War II magazine. Subscribe here.