He steered clear of the Confederate columns for eight days, returning only as Lee’s army slipped across the Potomac River at Williamsport, Md., and back into Virginia. “He seemed to be really glad that he had got home again,” reported his slave-owning mistress Martha Twyman, who was unable to pry any more details out of her reticent bondsman. “I afterwards asked him about it, but he evaded my questions, and I could get nothing further from him, in relation to it.” For Beverly, the Gettysburg Campaign was another cruel reminder of the painful ironies and heartrending conditions of American slavery.

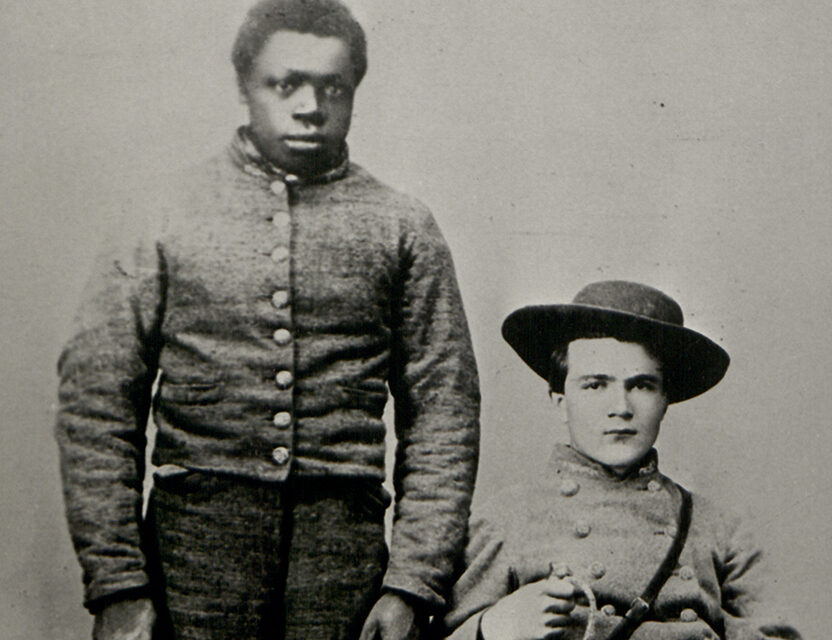

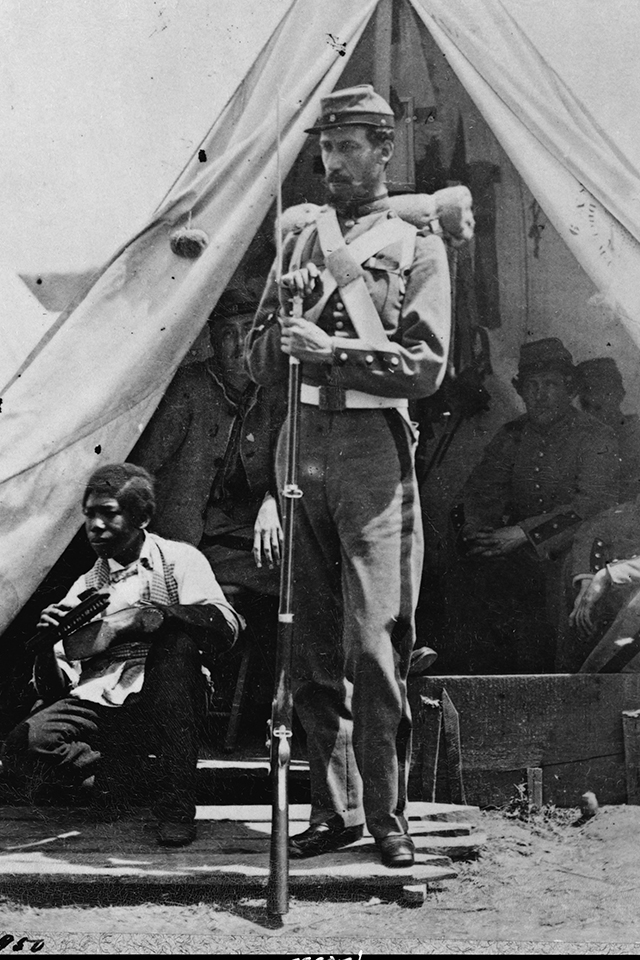

Slaves were ubiquitous in Confederate armies dating back to the war’s earliest days. Legions of enslaved people labored as servants, cooks, and teamsters, helping to free Southern whites to fight. In May 1861, an Alabama recruit’s first taste of camp life included winding his way through “throngs of negro cooks.” As they adjusted to army life, Confederate soldiers frequently wrote home, imploring relatives or acquaintances to “send me a negro boy.”

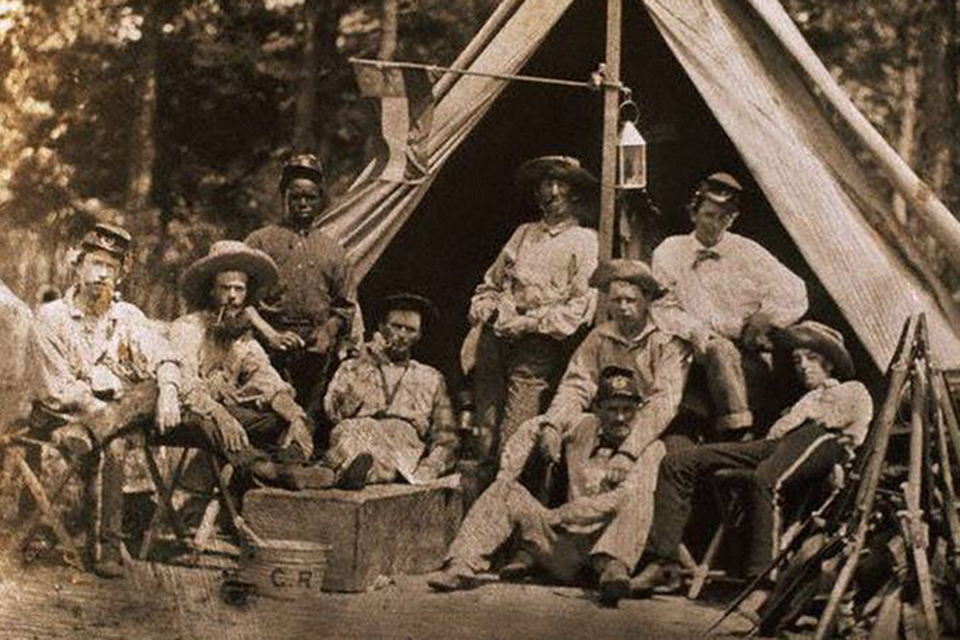

The presence of slaves allowed Lee’s soldiers to configure their camps as “small Southern communities,” in which bondsmen completed everyday tasks such as laundry, cooking, and caring for animals, while also seeing to their master’s personal comfort. While “a man can do everything that a soldier has to do,” reasoned a Mississippian who later joined Barksdale’s Brigade, “it is needlessly making a slave of himself if he can get some one else to do it for him.” Before his family sent an enslaved man named Jim to act as his servant, the Mississippi officer “scarcely had time to write a letter or read a line; now I have plenty to do both.”

Often lacking the funds to purchase their own slave, many enlisted men pooled their money to hire (or “rent”) an enslaved person from his master, or hire a free black servant. “We have hired a negro man to cook for us,” wrote one Confederate soldier. “We don’t pay but 80 cts a piece a month for him, and I had much rather pay that than to be standing over a hot fire cooking.” Samuel Burney and his mess mates in Cobb’s Georgia Legion shared a camp slave named Daniel, who “does all for us; brings wood, water, cooks, spreads down beds, blacks shoes, &c.” Although Daniel was not his slave, Burney seemed satisfied with his function as a shared servant, opining that he “does me as well as if he were mine.”

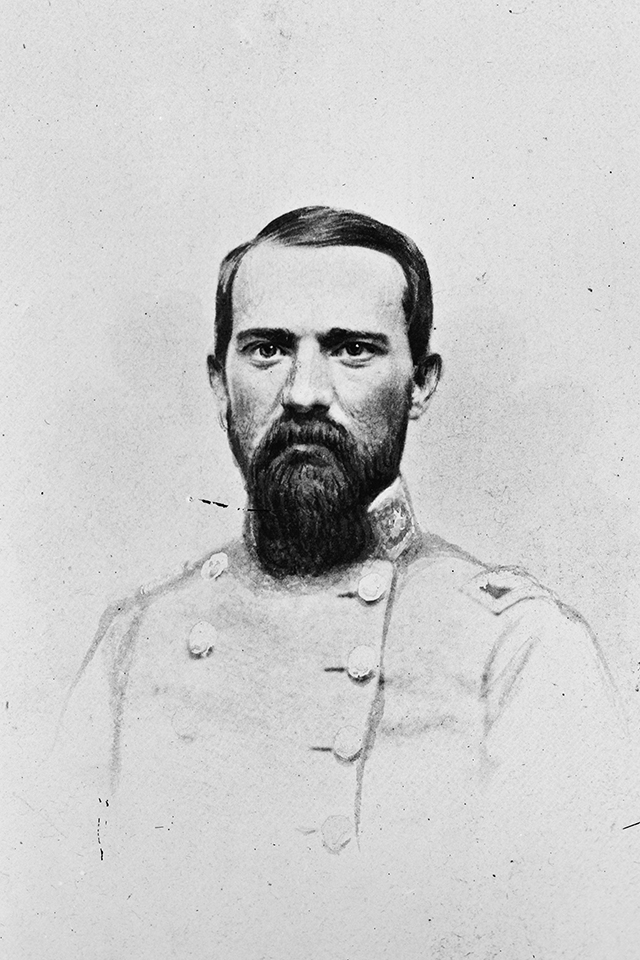

Life for camp slaves was often grueling and harsh. One of Lee’s divisional commanders, Maj. Gen. William Dorsey Pender, was “horrified

to see how white men calling themselves gentlemen neglect their poor helpless negroes in this camp.” Paralleling the experience of many soldiers, slaves fell ill in startling numbers as unsanitary conditions and exposure to new diseases took their toll. Pender, a North Carolinian, looked on with dismay as slaves and “free boys” alike—“in most cases forced from home,” he added—came down sick and “are allowed to die without any care on the part of those who are responsible for their well being.” And just like soldiers, homesickness plagued slaves who were separated from family and loved ones, often for prolonged periods of time.

To reconstruct the lives and experiences of enslaved people, historians are often forced to sift through diaries, letters, and reminiscences left by whites. Reading between the lines, we can attempt to recover some of what enslaved people experienced, but crucially not all of their thoughts, feelings, and motivations are clear to us. Accounts left by several disgruntled slave owners suggest that some slaves preferred the army as a welcome reprieve from monotonous labor at home, offering opportunities for travel generally unavailable to slaves in the antebellum period—and not to mention the improved prospect of escape to Union lines. During the summer of 1862, a Charlottesville, Va., slaveholder groused that this slave George ran away, and “passing as a free man” joined up with a Confederate artillery unit. Farther to the south, an Amelia County, Va., slave owner advertised for the return of a slave who had accompanied him during the Peninsula Campaign “and has since been anxious to go to the army again.”

Slaves and a small number of free African Americans might also have received cash for taking on additional tasks, or simply as a “bonus” for good work. Pender, who castigated the treatment of camp slaves, paid his servant Joe $15 per month—higher than the average Confederate private’s monthly wage ($11). Yet as events quickly demonstrated, Joe’s status was still secondary to that of white Confederate soldiers.

Shortly after the Antietam Campaign, Joe instantly aroused jealousy from white Confederate soldiers by purchasing “a nice gray uniform, french bosom linen shirt.” Pender determined that Joe would make no further purchases without his consent. “I have ordered him to allow me to be his treasurer,” Pender wrote home. Nor did Pender’s earlier criticisms prevent him from administering the lash. “I gave Joe a tremendous whipping last night,” Pender scribbled in a note to his wife. “He is a good and smart boy but like most young negroes needs correction badly.”

When slaves were near the front lines, amused Confederates drew on heavy dosages of slave vernacular and the “Sambo” stereotype, to depict them as clueless, “comical bystanders,” who lacked the battlefield courage of white Southerners. Shortly after the First Battle of Manassas, the Richmond Enquirer ran a satirical column about a camp slave named Sam who had purportedly followed his master into the thick of the “popin of de guns.” Sam wrapped up his story with a joke that seemed to place him in lockstep with white Confederates. Why was the place of battle called Manassas, he asked? Because “de abolitioners met us dar—we was de ‘men’ and day de ‘asses.’” While Sam’s parting quip—if indeed his own words—might have conveyed some vague sense of camaraderie, white Southerners were quick to remind him and other camp slaves of their secondary status. Reading the Enquirer from his camp in northern Virginia, a member of the 16th Mississippi copied the joke into his diary—complete with slave vernacular. Rolling with laughter, he recorded its provenance from “one of our negro cooks.” Although Sam’s story was that of a slave on the front lines, this Mississippi soldier—along with most white Southerners—considered Sam first and foremost a slave, not a fighting man.

The loyalty of Confederate slaves has proved a bedeviling topic in public memory of the Civil War. During the conflict, Southern papers churned out sentimental stories of “faithful” slaves combing battlefields to retrieve the bodies of their wounded or slain masters, anecdotes that painted the slave system in a harmonious and favorable light. In postwar reminiscences, former Confederates extolled the virtues of their similarly “devoted” slaves. Remarkably, many recent websites, books, and articles have accepted these claims as fact—with little or no critical analysis. Some have even gone as far as to declare broadly that the Southern Army’s legion of camp slaves were active supporters of the Confederacy.

During the war, most Confederates believed their slaves were loyal. “Out of the many negroes in this army I haven’t known one to even try to make his escape to the enemy,” boasted James Paul Verdery of the 48th Georgia. “There are several in my Reg’t and they are all so well contented, that every thing moves along easy with them.” When slaves did escape, disgruntled Confederates echoed the accusations that slaveholders had been repeating for decades—a third party, an abolitionist or a “Yankee,” had “seduced” their slave into leaving.

Most Confederates were unwilling or unable to believe that slaves had legitimate reasons for leaving, much less the agency and wherewithal to plot their own escapes. An Alabama officer leveled just such an accusation after his “negro cook” Charles ran away in 1864. “My opinion is that he was enticed away or forcibly detained by some negro worshipper,” the Alabamian reasoned, “as he had always been prompt and faithful, and seemed much attached to me.”

Largely convinced of their slaves’ loyalty, Confederates confidently toted their human property into a Northern free state. Slaves had accompanied the Army of Northern Virginia into Maryland in September 1862, but the Gettysburg Campaign would mark the first and only time Lee’s army carried a substantial number of slaves into a free state. While the British observer Arthur Fremantle recorded that each of Lee’s regiments had from “twenty to thirty negro slaves,” the precise number of camp slaves the Army of Northern Virginia brought to Gettysburg remains unknown. Estimates ranged as high as that of Thomas Caffey—another Englishman, serving as a Confederate artillery officer—who placed the number at 30,000 “colored servants who do nothing but cook and wash,” to the more conventional figure of 6,000–10,000, adopted by most scholars.

As Lee’s columns entered Pennsylvania in late June 1863, Confederates were eager to establish their slaves’ loyalty. From Mercersburg, Confederate surgeon Thomas Fanning Wood proudly reported that a slave in his brigade had refused the invitation of local “abolition women” to help him escape. “Our negroes are not at all prepossessed with their Yankee brethren,” Wood wrote home, “and I don’t suppose one in the Regt. could be induced to leave.” Confederates seized upon their slaves’ supposed loyalty on free soil to paint a picture of affectionate master-slave relationships and a benign slave system. “A chance for freedom they had,” bragged Private William S. White of the 3rd Richmond Howitzers, “but they preferred life and slavery in Dixie to liberty at the North.” Thoroughly coached in proslavery paternalism, White predicted that freedom would be an “absolute curse” to “careless” African Americans, who would “ever miss their kind and considerate masters.”

Some even claimed that slaves were more eager than white Confederates to wreak havoc on Yankee territory, in revenge for the hard war waged throughout much of the Union-occupied South. General Pender boasted that his servant Joe “enters into the invasion with much gusto and is quite active in looking up hidden property.” Pender maintained the excitement extended beyond just Joe and included the army’s entire accompaniment of slaves, who “seem to have more feeling in the matter than the white men and have come to the conclusion that they will [im]press horses, etc., etc. to any amount.” Members of the Washington Artillery of New Orleans (Eshleman’s Battalion) similarly testified that Lee’s General Orders No. 72—instructing Confederates to respect civilian property—came “much to the disgust of the negro cooks, who cannot understand why the army should act so differently from the Federal armies in Virginia.”

These claims require more context. Although Pennsylvania was a free state, throughout the Gettysburg Campaign Confederates occupied large swaths of the south central part, and were already rounding up blacks without regard to their legal status. Escape, under these circumstances, would have amounted to a “suicide mission,” in the words of scholar Colin Woodward. Not only that, but despite their own aspirations for freedom, many bondsmen remained tied to the South through enslaved family members back home. Just like the Virginia slave Beverly, the prospect of a prolonged, perhaps permanent separation from loved ones—coupled with fears of retribution against relatives still in bondage—discouraged many slaves from running away once the army reached Pennsylvania soil.

Similarly, the excitement Pender and others attributed to their slaves could stem from a multitude of factors, not just zealous loyalty to the Confederate cause. Most slaves had spent their entire lifetime in slavery, and the past several years in war-torn Virginia. The southern Pennsylvania countryside, by comparison, seemed a veritable cornucopia of agricultural bounty. Just as white Southern soldiers ate well in Pennsylvania, so too did the army’s contingent of slaves. And if camp slaves were eagerly searching for stashes of food and livestock, in many cases it was because their masters ordered them to do so.

Family ties likely influenced George, the slave of an English-born Confederate officer. On July 1, 1863, George’s master, Colonel Collett Leventhorpe, led his 11th North Carolina Infantry (Pettigrew’s Brigade) across Willoughby Run and smashed into the left flank of the famed Iron Brigade. In the furious fighting that blanketed Herbst Woods, Leventhorpe fell with wounds in his hip and arm. As the battle raged on to the east, the fallen colonel was joined by his slave. George “nursed his wounded master”—first at the impromptu field hospital set up at the Samuel Lohr farm, and later still in Union captivity, at hospitals in nearby Mercersburg, and eventually at Fort McHenry in Baltimore.

It was in Union hands that George’s story takes a surprising turn. “Discovering that he would be forced to become a Union volunteer,” a North Carolina paper later swanked, “he skillfully duped the Abolitionists by donning Federal uniform and by a feigned conversion to yankee philanthropy and bribery.” His deception complete, George procured a pass from a garrison officer to run some routine errands, and “with the aid of this pass…and by some strategy, George safely reached Dixie, as he says, ‘heartily sick of all yankees and all yankeedom.’”

If the North Carolina newspapers that celebrated George’s tale were to be believed, here was a slave running away to the South. Yet just months earlier, the colonel’s wife had offered George a potent reminder of the family ties that probably motivated his return. “Tell George his Mother & all are well,” Louisa Leventhorpe added in a letter to her husband written in February 1863.

George’s return was not the only such instance. On July 6, several slaves belonging to the 3rd Richmond Howitzers were captured by Union forces, only to return to Confederate lines three days later. An enslaved man by the name of George Washington also returned south. Washington was owned by Joseph Bryant of Bossier Parish, La., who hired him out as a cook to Private Burrel McKinney of the 9th Louisiana (Hays’ Brigade). Washington was “captured by the Yankees with our wagon trains in Pennsylvania,” but escaped, swam across the Potomac River, and eventually made his way to Richmond. There he was jailed as a runaway, and his ultimate fate remains uncertain. While Confederates viewed their slaves’ return as proof of unflinching loyalty, in most cases enslaved people’s true allegiances rested with their family members, who remained in bondage.

While each of these men had their own, perhaps complicated reasons for returning south, the vast majority of enslaved people made their loyalties known. The claims of fidelity and devotion that Southern diarists and columnists were all too eager to trumpet unraveled before their eyes as the war progressed. Through word-of-mouth and eavesdropping, slaves learned of the rise of the Republican Party, Lincoln’s election and the outbreak of war. When the opportunity presented itself, slaves consistently ran to—not from—Union lines. The wartime “desertion” of more than half a million slaves undermined many Southerners’ long-held proslavery convictions.

“As to the idea of a faithful servant, it is all a fiction,” the North Carolina diarist Catharine Devereux Edmondston concluded in September 1863. “I have seen the favourite & most petted negroes the first to leave in every instance.” According to General Joseph Johnston, “desertion” also plagued Confederate armies’ camp slaves. “We never have been able to keep the impressed Negroes with an army near the enemy,” he admitted in January 1864. “They desert.”

Even Robert E. Lee acknowledged in May 1863 that “our negroes” constituted “the chief source of information to the enemy.” Escaped slaves often proved valuable informants to the Army of the Potomac’s intelligence chief, Colonel George H. Sharpe. Just days after Lee’s cautionary epistle, a slave who ran away from Brig. Gen. George H. Steuart’s Brigade correctly informed one of Sharpe’s men that the Confederate army “intended to march to the [Shenandoah] valley and visit Maryland.” A week later, after the fight at Brandy Station, Va., two slaves identified as officer’s servants came into the Union lines and shared more valuable information. One enslaved man, a servant in Cobb’s Legion, confirmed the presence of Lee and all three corps commanders at a recent review in nearby Culpeper, while also shedding light on the army’s trajectory toward Pennsylvania.

“A great many negroes have gone to the Yankees,” wrote Edgeworth Bird, a quartermaster for Benning’s Georgia brigade, in a letter dated July 9. A Chambersburg minister who had taken special note of the Southern army’s sizable contingent of “colored servants and teamsters” reported rumors that some had deserted. Just how many camp slaves escaped during the Gettysburg Campaign remains unknown, though several individual cases do survive. An enslaved man named Joe—who served a group of brothers in the 18th Mississippi—disappeared during the retreat from Gettysburg. Unwilling to completely forsake Joe’s loyalty, an advertisement for his return speculated that he “ran away…or was captured…on Gen. Lee’s retreat from Pennsylvania.”

During the retreat, Captain Charles Waddell of the 12th Virginia (Mahone’s Brigade) briefly left the regiment, returning to find that his slave Willis had seized the opportunity to escape, taking with him Waddell’s camp equipage. And while his slave did not escape, Captain Shepherd G. Pryor of the 12th Georgia (Doles’ Brigade) expressed frustration with the newfound assertiveness of his camp slave, Henry. As the army entered Pennsylvania, Henry became “very trifling,” Pryor wrote, and “dont care for any thing but to make money for himself.” Pryor thought that Henry “will get better” once he “got farther away from the free states.”

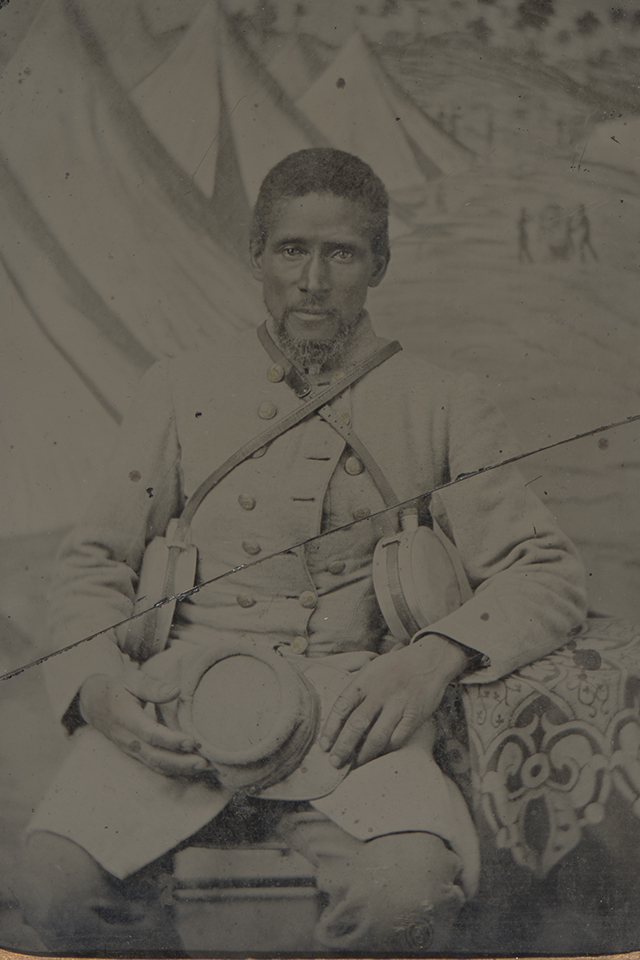

Many camp slaves who fell into Union hands were brought to Baltimore’s Fort McHenry. By July 30, the fort’s commandant, Brig. Gen. William W. Morris, could count 64 “Negroes, Servants of Officers in the Rebel Army” from Gettysburg and the retreat. Shortly after their arrival, the men were visited by Colonel William Birney—the older brother of Maj. Gen. David Bell Birney, who had fought at Gettysburg and whose father was a prominent prewar abolitionist. During the summer of 1863, Birney was in Baltimore tasked with recruiting U.S. Colored Troops—often concentrating his efforts in the city’s slave pens and prisons, much to the ire of Maryland slaveowners. When word of the captured camp slaves reached him, Birney headed directly to Fort McHenry. There the abolitionist colonel “appealed to them as freemen,” and pointing to the “glorious” stars and stripes floating above, “urged them to assert their rights, and strike the blow that should deliver their oppressed brethren from the tyranny of their so called masters.”

At least 16 followed Birney’s call and enlisted, while another eight left with Union regiments as cooks. Morris was optimistic that the remaining number might be employed as “laborers, teamsters, &c&c,” though he noted that several of the men declared themselves to be free, “and have families to whom they desire to return.” Union officials debated this request, though Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton ultimately decided that no black detainees would be sent south. Still, at least six managed to escape—a testament to the strength of family bonds.

For enslaved people, the Gettysburg Campaign had a wholly different meaning than the decisive Union victory celebrated in Northern papers, or the bitter defeat that Southerners only begrudgingly conceded. Stepping foot on free soil (most likely for the first time), they confronted a cruel dilemma—family or freedom. While some took flight as opportunities presented themselves, others stayed put, aspiring to keep their families intact despite slavery. Like Beverly, they were forced to maintain a painful, evasive silence about their heart-wrenching brush with freedom, a uniquely human story of Gettysburg that remains largely untold.

The Myth of ‘Black Confederates’

The African Americans accompanying the Army of Northern Virginia as camp slaves were noncombatants. The myth of “Black Confederates” has misconstrued and distorted the nature of slavery within Confederate armies. Many proponents of the myth point to a post-battle report published in the New York Herald on July 11, 1863, which counted “among the rebel prisoners…seven negroes in uniform and fully accoutered as soldiers.” These men, however, were not soldiers, but among the thousands of camp slaves accompanying Lee’s army. If anyone would be baffled by modern-day claims about “Black Confederates,” it would be Confederate soldiers. Decades of antebellum slave codes in Southern states had strictly curtailed African-Americans’ access to firearms, and most Confederates warmed to the idea of arming blacks only during the winter of 1864-65, and even then only out of sheer desperation to continue the fight for independence.

At Gettysburg, enslaved people were present in large numbers in the Army of Northern Virgina, but not in the battle lines sweeping toward Union positions. Camp slaves occupied much of the First Day’s battlefield after it was firmly in Confederate hands, tending to the wounded, cooking meals for Southern soldiers, and caring for the army’s multitude of horses and animals. After the fighting on July 1 had concluded, Confederate artillery officer Coupland R. Page met his “negro boy, Pete” along the Chambersburg Pike west of town. Pete had “kindled a bright fire” and procured food from “four full haversacks” scavenged off the lifeless corpses of Union 1st Corps dead. “He then took my horse, fed him, and returned to the fire,” recalled Page. “By 8 o’clock my mess were all filled with real coffee and other substantials.”

A prisoner from the 1st Minnesota encountered a similar scene on the morning of July 3, as he was escorted behind Confederate lines, observing “long lines of negro cooks baking corn pone for rebel soldiers at the front.” Once the firing sputtered to a close, many camp slaves were faced with the unenviable task of traversing the battlefield in search of their wounded or potentially slain masters. “Negro servants hunting for their masters were a feature of the landscape,” recalled Confederate artillerist Edward Porter Alexander. When referring to camp slaves, Confederate soldiers consistently used the terms “servant,” “cook,” or “negro”—making a clear distinction that the African Americans traveling with Lee’s army were laborers and servants, not soldiers.

Cooper H. Wingert is a historian and the author of 12 books, including The Confederate Approach on Harrisburg, Slavery and the Underground Railroad in South Central Pennsylvania and Abolitionists of South Central Pennsylvania. Wingert has appeared on CSPAN Book TV, and is currently a student at Dickinson College.