In 1918 Captain George S. Patton Jr. sent his wife, Beatrice, a blow-by-blow account of his role in the Saint-Mihiel offensive.

When the United States entered World War I in April 1917, Major General John J. “Black Jack” Pershing was made the commander of the American Expeditionary Forces on the Western Front, and he brought Captain George S. Patton Jr. with him to France. Patton had joined Pershing’s staff the year before, accompanying him on a military expedition into Mexico to hunt down Pancho Villa.

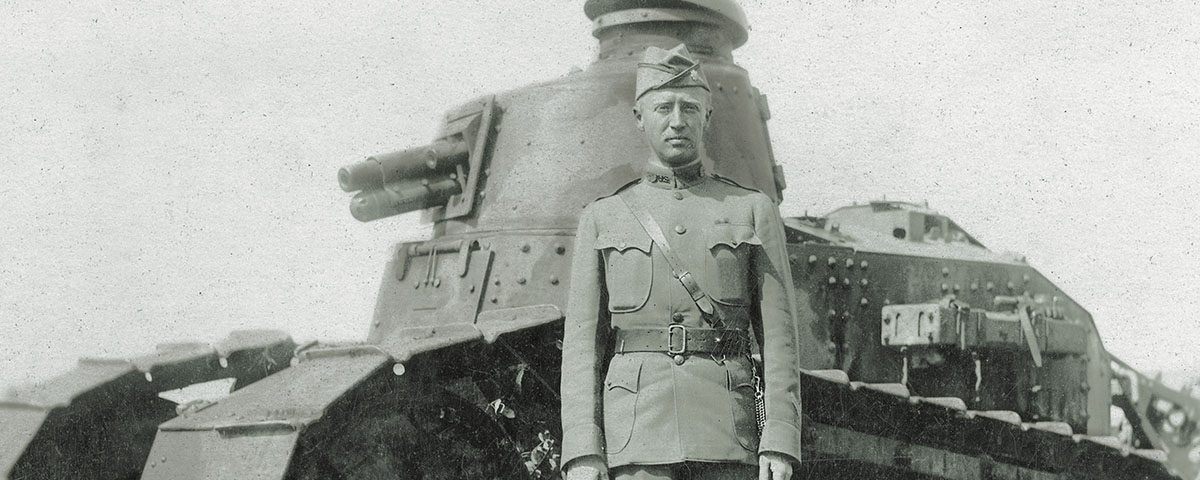

In November 1917 Patton, newly promoted to major, left Pershing’s headquarters staff to become the first officer in the new U.S. Army Tank Corps. In the ensuing months he would organize and train the new tank units; he was also promoted to lieutenant colonel.

Patton would go on to become an expert practitioner of mobile tank warfare in the European and Mediterranean theaters during World War II. After he warned his men, who both feared and admired him, that they would be up to their necks in blood and guts, they took to calling him “Old Blood and Guts.” He died on December 9, 1945, after seriously injuring his head and spine in an automobile accident.

Throughout his career Patton wrote loving, supremely candid, and often touching letters to his wife, Beatrice, whom he married less than a year after graduating from West Point in June 1909. “I am not so hellish young and it is not spring,” he wrote in one of them, “yet still I love you just as much as if we were 22 again on the baseball grandstand at West Point the night I graduated.” Another time, after a gasoline lantern exploded and badly burned his face, Patton wrote, “I love you with all my heart and would have hated worst to have been blinded because I could not have seen you.”

On September 12, 1918, Patton led the first U.S. tank units into battle during the Saint-Mihiel offensive. To inspire his men, he often led from the front, for example, walking ahead of the tanks into the German-held village of Essey and riding on top of one during the advance into Pannes until he was forced off by enemy machine gunners.

In the letter to Beatrice that follows, Patton recounted, in great detail, his role in the Saint-Mihiel offensive. Dated September 16, 1918, it is one of six of Patton’s letters to his wife that appear in Pershing’s Tankers: Personal Accounts of the AEF Tank Corps in World War I, edited by Lawrence M. Kaplan (University Press of Kentucky, 2018).

Darling Beat:

The news is out, so I can give you a brief account of the battle of St. Mihiel, etc. At 10 a.m. August 22 I got a telephone message to report to Gen. R. [Brigadier General Samuel Rockenbach] with my reconnaissance officer ready for protracted field service. I did, at 3 p.m. We were at Army HQ and had been told the plans, which as you know, contemplated the attack by III Corps. I was to command the tanks in the V Corps. The rest of the tanks were to be supplied by the French. At 6 p.m. I reported to your old friend Gen. Burtt [Brigadier General Wilson B. Burtt] (Capt. in Mexico) who was chief of staff. Next day I went to French corps HQ to get permission to visit the front. On going there I was told it was a marsh where tanks could not move. As I did not believe this, I went out with a French patrol that night to the Bosch [Boche, nickname for the Germans] wire and found the ground hard and dry, though in winter it is probably a marsh. We worked hard and got all ready to fight; also got our tanks, for on August 22 we had only 22. I had to patrol and make plans and then travel back to the center every other night, a four-hour ride, to arrange things there. We thought that “D” day would be September 7. On September 4, I got ordered to leave the V Corps and report to the IV Corps near Toul. Here I got a new job and had to start all over again, which was a bore; still it had to be done.

I walked down the Rupt de Mad by day to the bridge at Xivray, which is in no man’s land and was not shot at. I had to do it to see whether we could cross the stream.

Then we started to detrain and that was awful for four nights. The French made every mistake they could, sending trains to the wrong place or not sending them at all. The last company of the 327 Battalion detrained at 3:15 a.m. and marched right into action.

We attacked at 5 a.m. on Thursday, September 12. At 1 a.m. 900 plus guns opened and shot till 5. It was dark with a heavy rain and wind. I was on a hill in front of the main line where I could watch both battalions and 30 French that I had also under me.

I could see them coming along and getting stuck in the trenches. It was a most irritating sight. At 7 o’clock I moved forward two miles and at 9 o’clock I decided I had to see something, so I took an officer and three runners and started forward.

There were very few dead in the trenches, as the Bosch had not fought hard, but you never saw such trenches—eight feet deep and 10 to 14 feet wide. At the first town we came to, St. Baussant, the Bosch were still shelling and it was not pleasant. At [Maizerais] I found the French stuck in a place under shell fire. I talked to the major and went on. I had not gone 20 feet when a shell, six inches, struck the tank he was working on and killed 15 men. I went on toward Essey and got into the front line infantry who were laying down. As there was only shell fire, I walked on smoking with vigor; most of the shells went high. Here I met [Brigadier] Gen. MacArthur (Douglas) commanding a brigade. He was walking about too, so we stood and talked, but neither was much interested in what the other said as we could not get our minds off the shells. I went up the hill to have a look and could see the Bosch running beyond Essey fast, then five tanks of my right battalion came up, so I told them to go through Essey. Some damned Frenchman at the bridge told them to go back as there were too many shells in the town. The lieutenant in command obeyed. This made me mad, so I led them through on foot, but there was no danger as the Bosch [were] shelling the next town.

Some Germans came out of dugouts and surrendered to Gen. MacArthur.

I asked him if I could go on and attack the next town, Pannes. He said sure, so I started. All the tanks but one ran out of gas. When we got to Pannes, some two miles, the infantry would not go in, so I told the sergeant commanding the tank to go in. He was nervous at being alone, so I said I would sit on the roof. This reassured him and we entered the town. Lieut. Knowles [First Lieutenant Maurice H. Knowles] and Sgt. Graham sat on the tail of the tank. I watched one side of the street and they the other. Pretty soon we saw a Bosch who threw up his hands. I told Knowles and Graham to go get him and I went on outside the town toward Beney. I saw the paint fly off the side of the tank and heard machine guns so I jumped off and got in a shell hole. It was small and the bullets knocked all of the front edge in on me. Here, I was nervous. The tank had not seen me get off and was going on. The infantry was about 200 meters back of me and did not advance. One runner on my right got hit. If I went back the infantry would think I was running. If I did not, they would not support the tank and it might get hurt. Besides, machine gun bullets are unpleasant to hear.

Finally, I decided that I could get back obliquely, so I started as soon as the m.g.’s [machine guns] opened. I would lay down and beat the bullets each time. The captain of doughboys said he could not advance, as the troops on his right were not up. I asked him to send a runner to the tank to recall it. He said it was “not his tank,” so I went and I burned the breeze too, so did the bullets. I kept the tank between me and the bullets as much as possible and finally got it back. By this time four more tanks had come up, but there was no officer. I put Lieut. Knowles, who had caught 30 Bosch instead of one, in the tank and asked the infantry if they would follow. They said yes, so I started the tanks. In the meantime, some of our m.g.’s had pushed out in front and one tank thought they were Bosch and began to shoot at them. I had no time to get someone, so we went out again. The tanks went on to Beney, but the infantry swerved off to the right and I sent a lieutenant out to change direction of the tanks. Then I followed the advance on foot, but there was not much shooting. The tanks had scared the Bosch away.

From here I walked along the line of battle to the left flank at Nonsard where the other battalion was. The captain who would not send a runner was killed at this time. I was very tired indeed and hungry as I had lost the sack with my rations and my flask of brandy. At Nonsard I found 25 tanks. They had taken the town and only lost four men and two officers, but they were out of gas. All my runners were gone, so I started back seven miles to tell them to get some gas. That was the only bad part of the fight. I had had no sleep for two nights; nothing to eat since the night before except some crackers I got off a dead Bosch. I would have given a lot for a little brandy, but even my water was gone.

When I got to [censored] it had been raining two hours and the mud was bad.

Here I met an officer sightseeing and he gave me a lift. This was lucky as the car got stuck in a jam and went slower than the men on foot and an airplane dropped a bomb on the road and killed two soldiers who had been walking just back of me.

I got a motorcycle and got the gas and reported to the court. The 13[th] we did nothing. I will tell you of the 14[th] later.

This is a very egotistical account of the affair full of “I” but it will interest you.

I at least proved to my satisfaction that I have nerve. I was the only man on the front line except Gen. MacArthur who never ducked a shell. I wanted to, but it is foolish, as it does no good if they are going to hit you, they will.

I had in this action 144 tanks and 33 French tanks; quite a command. We lost two tanks with direct hits and eight men and three officers only, one killed and one lost an eye.

All the losses were small, absurdly so. The great feat the tanks performed was getting through at all. The conditions could not have been worse. Only 40% did it the first day, but we had 80% up by morning. The men were fine. Nearly all the officers led the tanks on foot.

Gen. R. [Rockenbach] gave me hell for going up, but it had to be done—at least I will not sit in a dugout and have my men out in the fighting.

I am feeling fine and just at present have little to do….

Personally, I never fired a shot except to kill two poor horses with broken legs.

I love you with all my heart.

[hr]

This article appears in the Spring 2019 issue (Vol. 31, No. 3) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Tanks for the Memories

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!