On April 18, 1945, at around 10 o’clock in the morning, U.S. Army lieutenant colonel Joseph B. Coolidge and four other men were bumping along in a jeep on a shell-pitted dirt road some 200 yards from the beach at Ie Shima (now Iejima), a small island just off the northwest coast of Okinawa, Japan. Coolidge, commanding the 305th Regiment, 77th Infantry Division, was en route to his forward command post; the others were bumming a ride. The road had been cleared of mines, booby traps, and other hazards, but it offered a clear line of sight to a coral ridge 300 yards away. Without warning, a Japanese machine gunner opened fire. The men jumped clear, tumbling into a roadside ditch. Coolidge and one of the other men, both of whom should have known better, raised their heads to look around. “Are you all right?” the man asked. Before Coolidge could reply, there was another brief burst of fire. Coolidge fell backward, unhurt, but his companion sagged to the ground, killed instantly by a bullet to the left temple, just below his helmet.

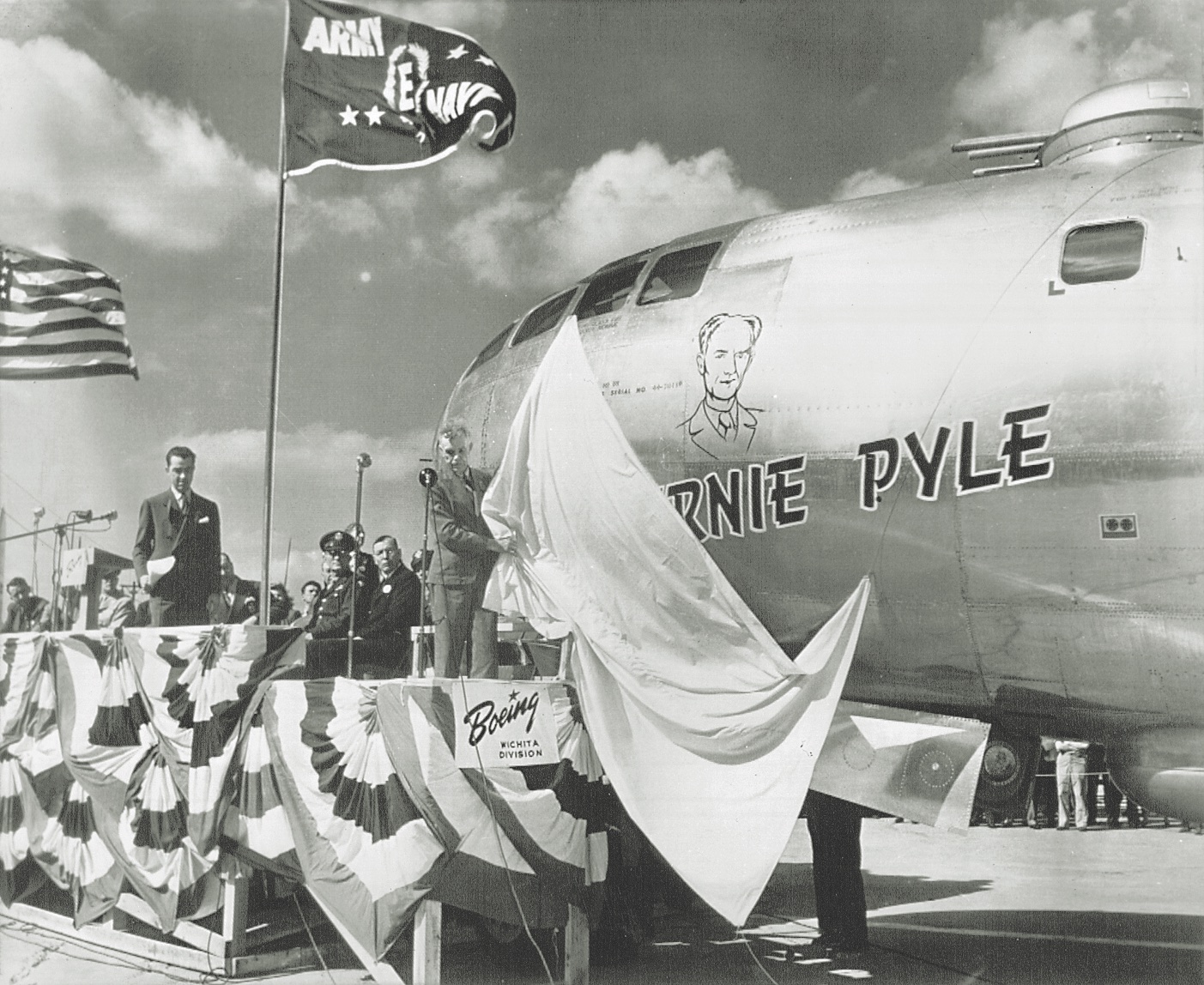

His name was Ernie Pyle, and at the time of his death he was the world’s most famous war correspondent, perhaps the most famous in American history. Certainly, he was the best liked. It was fitting that Pyle used his last words to ask about a fellow American soldier: He’d spent the past three years doing just that, in person and in print. “Ernie Pyle, the Soldier’s Friend,” his newspaper editors styled him, and millions of readers back home with husbands, fathers, sons, brothers, sweethearts, and friends serving on the front lines of World War II counted on Pyle to keep them informed of their loved ones’ lives—and, all too often, their deaths. Pyle took that responsibility very seriously, and it ultimately wore him down physically and mentally. Indeed, it may have been sheer exhaustion, more than anything, that unaccountably caused the veteran combat observer to raise his head while under fire at Ie Shima.

Pyle had frequently told his wife and colleagues that he was worn out. He didn’t expect to survive his current assignment, yet he felt he owed it to “the boys” to cover what was shaping up to be the last American campaign of the war. While sailing on a troopship from Western Europe to Okinawa, he had already written, but not filed, what turned out to be his final newspaper column. “And so it is over,” his handwritten draft read. “The day that had so long seemed would never come has come at last.” He was referring to the looming Allied victory in Europe, but he might as well have been speaking about his own fate. “The companionship of two and a half years of death and misery,” he went on to observe, “is a spouse that tolerates no divorce.”

At the White House President Harry S. Truman announced Pyle’s death with a matter-of-factness that the correspondent would have appreciated. “The nation is quickly saddened again by the death of Ernie Pyle,” Truman said. “No man in this war has so well told the story of the American fighting man as American fighting men wanted it told. He deserves the gratitude of all his countrymen.” It was only six days after the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt, Truman’s towering predecessor. In one of the saddest ironies of a sad and often ironic war, neither the American president who tirelessly prosecuted the war nor the journalist who most piercingly reported on it lived long enough to see the victorious end of the fighting. Their personal wars ended first.

Handsome, patrician, urbane New York native Franklin Roosevelt had little in common with homespun Hoosier farm boy Ernie Pyle. Born in the flyspeck village of Dana, Indiana, on August 3, 1900, Pyle yearned for a life beyond the windswept flatlands of his home state. At age 18 he enlisted in the U.S. Naval Reserve, but World War I ended before he could complete basic training. He enrolled at Indiana University in 1919, majoring in economics but concentrating on journalism. Pyle served as the editor of the Indiana Daily Student and worked on the yearbook staff before he left college one semester shy of graduation in 1923 to take a job as a reporter for the Daily Herald in LaPorte, Indiana.

For the next dozen years Pyle worked for various newspapers in Washington, D.C., and New York City. He achieved some measure of national fame as “the Hoosier Vagabond,” crisscrossing the country and writing human-interest features for the Scripps-Howard newspaper chain. His work as a columnist brought him into contact with common, hardworking men and women, and he honed a simple, plainspoken writing style, one that highlighted his sharp eye for detail as well as his inherent sympathy for the struggling underdogs of Depression-era America. With his wife, Jerry, at his side, Pyle visited all 48 states, plus Alaska, Hawaii, and parts of Central and South America. In his travels he talked with thousands of people—from the soda jerk in small-town Iowa to Park Avenue millionaires to Hollywood movie stars. True to form, he favored “the little man.”

When World War II broke out in Europe in 1939, Pyle said he sensed that it would be “a war to end everything.” He traveled to London in 1940, arriving in time to witness and report on the Nazi terror bombings known as the Blitz. He was sitting in his room at the Savoy Hotel on December 29 when 130 German bombers struck London in one of the largest incendiary raids of the war. Spurning the safety of the hotel’s basement bomb shelter, Pyle watched from his balcony as nearly 2,000 fires broke out in the city, some near historic St. Paul’s Cathedral. His graphic cable to New York described a “London stabbed with great fires, shaken by explosions, its dark regions along the Thames sparkling with the pinpoints of white-hot bombs, all of it roofed over with a ceiling of pink that held bursting shells, balloons, flares.” Through the rosy smoke he beheld the famous dome of St. Paul’s, still standing in the mayhem “like a picture of some miraculous figure that appears before peace-hungry soldiers on a battlefield.”

Time magazine reprinted Pyle’s column, calling it “one of the most vivid, sorrowful dispatches of the war” while pointing out that “until last week Ernie Pyle, an inconspicuous little man with thinning reddish hair and a shy, pixy face, was not celebrated as a straight news reporter.” His reputation was made. Roy W. Howard, the all-powerful head of Scripps-Howard, wired Pyle: “your stuff not only greatest your career, but most illuminating human and appealing descriptive matter printed america since outbreak battle britain.” Pyle continued sending columns from war-torn England for the rest of the year.

Pyle returned to the States the next spring to attend his mother’s funeral and nurse his troubled alcoholic wife back to health after the first of several suicide attempts. Fans besieged him everywhere he went in his newly adopted hometown of Albuquerque, New Mexico. So many people drove past the couple’s modest ranch house that Pyle had to rent a hotel room downtown to complete two new columns for an upcoming book of his London pieces, Ernie Pyle in England. He began planning a trip to the Far East to find new subjects to write about but had to scrap it when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.

Though he was 41, Pyle briefly entertained the notion of joining the American armed forces. The navy rejected him as too small (he was 5 feet 8 inches tall and weighed 110 pounds), and he ultimately decided against enlisting in the army. Instead, in June 1942 he accepted an assignment from Scripps-Howard to tour new American bases in England and Ireland. Four months later he accompanied U.S. forces to Algeria to prepare for a U.S.-British offensive in North Africa. At a forward air base at Biskra in mid-January 1943, Pyle witnessed his first combat fatality, the pilot of a crippled B-17 Flying Fortress that crash-landed back at the base after losing two engines in a bombing raid over Tripoli, Libya. “One of the returning Fortresses had released a red flare over the field, and I had stood with others beneath the great plane as they handed its dead pilot, head downward, through the escape hatch onto a stretcher,” Pyle wrote. “The faces of his crew were grave, and nobody talked very loud. One man clutched a leather cap with blood on it. The pilot’s hands were very white. Everybody knew the pilot. He was so young, a couple of hours ago. The war came inside us then, and we felt it deeply.” Before the war was over, Pyle would see thousands more dead men of many nationalities, from North Africa to Western Europe to the coast of Japan.

In January 1943 Pyle attached himself to Major General Lloyd R. Fredendall’s II Corps infantry, headquartered at Tebessa, near Algeria’s border with Tunisia. He spent a month living with GIs in frigid mountain foxholes, sleeping on the ground, brewing coffee and cooking stew in a five-gallon gasoline can, and slouching next to the soldiers in chow lines. Unlike other correspondents, Pyle was relaxed and natural with the enlisted men, swapping stories about their hometowns, laughing at his own foibles, and never consciously attempting to guide conversations into ready-made articles. A New York soldier wrote to his father that Pyle was “a pleasant talker, easy-going and with a faculty for becoming ‘one of the boys’ in two seconds flat.” It was Pyle’s greatest strength as journalist, something he had learned in his years of traveling across back-roads America during the Depression, and it would serve him well throughout the war.

In mid-February, Pyle witnessed firsthand the embarrassing rout of green American forces by the battle-hardened German Afrika Korps at Kasserine Pass. After watching German panzers obliterate American tanks at Sidi Bou Zid, Pyle joined the soldiers in a chaotic retreat through the mountain passes that he described as “awful nights of fleeing, crawling and hiding from death.” Even then, he demonstrated his concern for the families of the young GIs, silently picking through the wreckage of a bombed jeep for scraps of clothing, paper, or anything that might reveal the identity of the three Americans killed in the bombing.

Pyle told the truth to readers back home, describing the defeat at Kasserine Pass as “damned humiliating” and “a complete melee.” Still, he reassured them. “You need to feel no shame nor concern about their ability,” he wrote of the fighting men he was accompanying. “There is nothing wrong with the common American soldier. His fighting spirit is good. His morale is okay. The deeper he gets into a fight the more of a fighting man he becomes.” He estimated that it would take the United States, a peace-loving country, two years to fully adjust itself to war. Once in action, it took the frontline soldiers considerably less time than that to “make the psychological transition from the normal belief that taking human life is sinful, over to a new professional outlook where killing is craft,” he wrote. “To them now there is nothing morally wrong about killing. In fact it is an admirable thing.”

Joining the 1st Infantry Division, the famous “Big Red One,” Pyle followed Major General Terry de la Mesa Allen Sr. and his men into battle at Bizerte, on the Mediterranean coast of Tunisia. “Terrible Terry” Allen soon became one Pyle’s favorite soldiers. The foul-mouthed Texan shared his headquarters tent with Pyle and always leveled with him about the progress of the campaign. “He didn’t give a damn for hell or high water,” Pyle wrote of Allen. “If there was one thing in the world Allen lived and breathed for, it was to fight. He hated Germans and Italians like vermin, and his pattern for victory was simple: just wade in and murder the hell out of the low-down, good-for-nothing so-and-so’s.”

Pyle accompanied the fighting men of the Big Red One as they hacked their way to Bizerte through waist-high wheat and up rocky hillsides held by grim-faced, seasoned German soldiers. “We’re now with an infantry outfit that has battled ceaselessly for four days and nights,” he reported. “This northern warfare has been in the mountains. You don’t ride much anymore. It is walking and climbing and crawling country. The mountains aren’t big, but they are constant. They are largely treeless. They are easy to defend and bitter to take. But we are taking them.”

Hastily scribbling notes from a foxhole as snakes, lizards, and scorpions crawled nearby and machine gun bullets sprayed dirt within 10 feet of him, Pyle conveyed to readers the reality of modern combat. “It ain’t no play,” he wrote. Before Pyle, war correspondents had traveled in the rear with the generals, reporting on grand strategy and largely repeating what they were told by self-interested commanders. Henceforth, with Ernie Pyle as a model, they followed the men into combat, “the God-damned infantry, as they like to call themselves,” Pyle reported, “the mud-rain-frost-and-wind boys that wars can’t be won without.” Following the Allied victory at Bizerte and Tunis (taken by the British Eighth Army) in May 1943, Pyle joined Operation Husky, the joint British-American invasion of Sicily. Tired and sick—he would spend five days in the hospital with “battlefield fever” amid the death rattle of fatally wounded soldiers—he carried on. “I’m getting awfully tired of war and writing about it,” he admitted to his wife. “It seems like I can’t think of anything new to say; each time it’s like going to the same movie again.” Often, he told her, he had to get good and drunk before he could go to sleep.

To Pyle’s surprise, his readers back home didn’t seem to mind seeing the same movie again—or at least his descriptions of it. Returning briefly to the States that September for the publication of his second book, Here Is Your War, after 428 days overseas, Pyle found himself besieged by autograph seekers, reporters, booking agents, advertising copywriters, intelligence officers at the Pentagon—even Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who invited Pyle to tea at the White House.

Here Is Your War climbed to the top of the bestseller lists, exhausting its first print run of 150,000 copies and forcing the publisher, Henry Holt and Company, to petition the government for more rationed paper to print extra copies, on the grounds that the book was good for American morale. Before returning to the front, Pyle finalized a deal with Hollywood producer Lester Cowan to make a movie based on his book. Cowan won the correspondent’s reluctant approval by promising to keep the usual movie “hokum” to a minimum and allowing Pyle to review the final script. Pyle subsequently met with the film’s chief screenwriter, a then unknown playwright named Arthur Miller, who would later win fame as the author of Death of a Salesman and The Crucible. But the two men didn’t see eye to eye on the movie’s direction, with the idealistic young Miller insisting that the movie be about large issues and Pyle insisting equally that it be about “the guys” at the front. In the end, the two writers agreed to disagree.

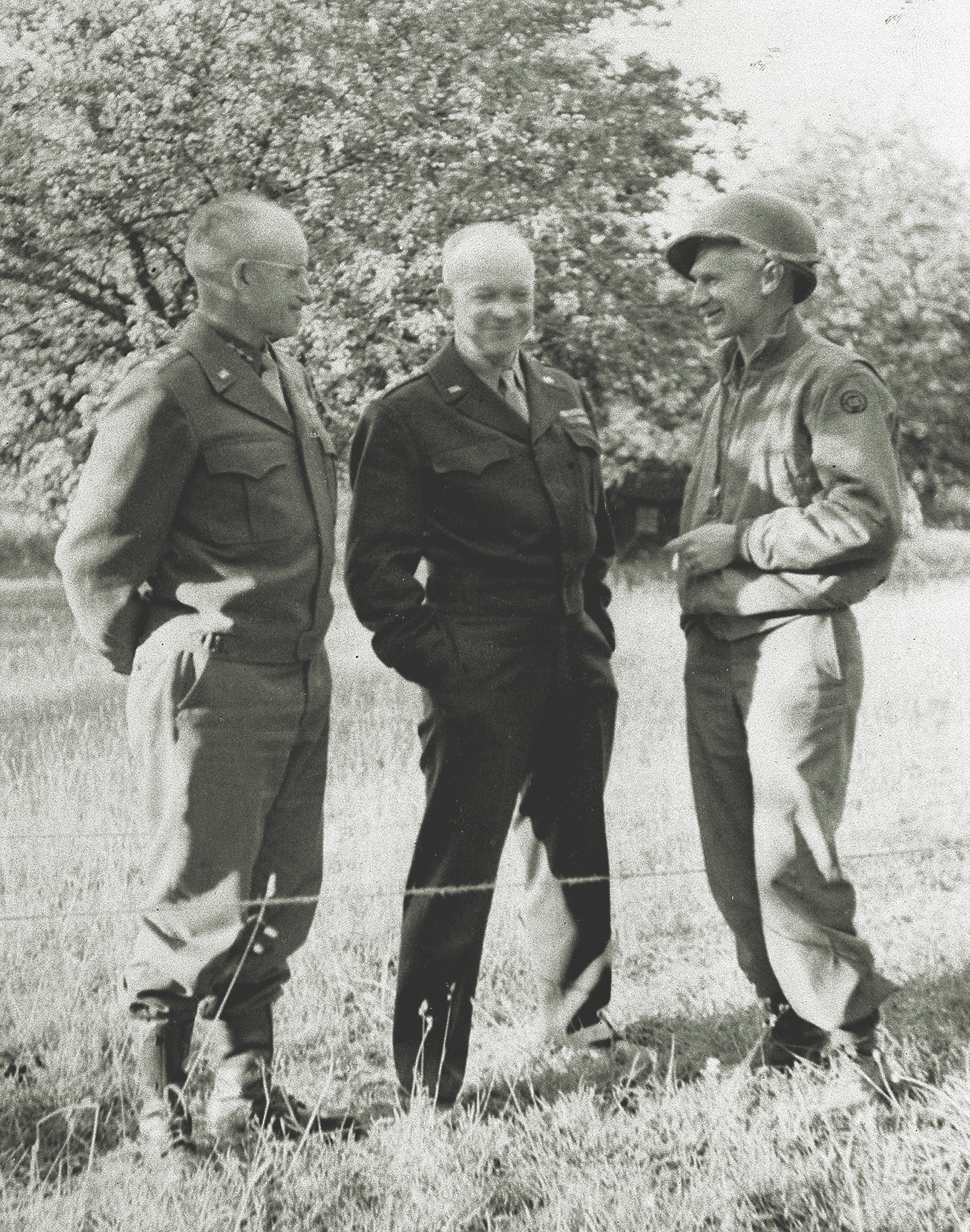

Pyle returned to the war in late November 1943, flying to Algiers, where he dropped off a copy of Here Is Your War at army headquarters for commanding general Dwight D. Eisenhower, and then hopping across the Mediterranean to Italy, where the U.S. Fifth Army was bogged down around Naples in knee-deep mud and heavy rains. It was the beginning of what Pyle called “the long winter misery” of the Italian campaign. Under Lieutenant General Mark W. Clark, the Fifth Army confronted a fiercely defended German line, 10 miles deep, in the jagged Apennine Mountains. Back at the front, Pyle reported on the army’s progress—or lack thereof. “The hills rose to high ridges of almost solid rock,” he wrote. “We couldn’t go around them through the flat peaceful valleys, because the Germans were up there looking down upon us, and they would have let us have it. So we had to go up and over.” The GIs, he said, were “living in almost inconceivable misery. Thousands of the men had not been dry for weeks. Other thousands lay at night in the high mountains with the temperature below freezing and the thin snow sifting over them. They dug into the stones and slept in little chasms and behind rocks and in half-caves. They lived like men of prehistoric times, and a club would have become them more than a machine gun.”

On December 14, Pyle found himself at the base of Mount Sammucro, also known as Hill 1205, where elements of the 36th Infantry Division were hunkered down in a shallow mine dug out of the clay hillside. The hill was so steep that supplies had to be hauled up by mules and then hand-pulled the rest of the way by rope. As Pyle looked on, he noticed a young soldier limping into view. The soldier, a private named Riley Tidwell, told Pyle that his company commander had been killed that morning by an enemy shell. The officer, Captain Henry T. Waskow of Belton, Texas, had pushed Tidwell out of the way before the shell exploded, striking the captain in the chest. “He was one of the finest men I ever met,” Tidwell told Pyle. The soldiers had to wait two more days and nights before they could bring Waskow’s body down the mountain on the back of a mule.

Pyle’s account of Waskow’s death became the most famous single dispatch of the entire war. As Pyle reported, the men in Waskow’s company filed past his body, one by one. “God damn it!” said one. “God damn it to hell anyway,” said a second. “I’m sorry, old man,” murmured a fellow officer. “I sure am sorry, sir,” said a fourth. One soldier held Waskow’s hand as he looked into the fallen captain’s face, straightened his collar, and rearranged his uniform as best he could. “The rest of us went back into the cowshed,” Pyle concluded. “We lay down on the straw in the cowshed, and pretty soon we were all asleep.”

“The Death of Captain Waskow” was instantly hailed as a classic of war reporting, reprinted by hundreds of American newspapers, read aloud on the radio, and reprinted as a War Bond promotion. The Washington Daily News splashed the column across its front page in large type, telling readers, “We thought Ernie Pyle’s story would tell you more about the war than headlines that Russians are 14 miles outside Poland.” Grove Patterson, the editor of the Toledo Blade, praised Pyle for “the most beautiful lines that came out of the whole dark and bitter conflict,” adding that his piece was “the most beautifully written newspaper story I have ever read, and that covers a lot of ground.” The article has been widely anthologized ever since, and the incident served as the dramatic climax of the 1945 movie The Story of G.I. Joe, starring Burgess Meredith as Ernie Pyle and a then little-known Robert Mitchum as Captain Waskow (renamed Walker in the movie).

Pyle next linked up with a hard-fighting rifle company—Company E, 168th Infantry Regiment, 34th Division—in the mountains north of Naples. It had been in combat almost continually since landing in Italy in September. Of the company’s 200 original members, only eight remained; the rest had been killed, wounded, transferred, or rotated home. Pyle concentrated on the remaining eight, particularly 28-year-old sergeant Frank “Buck” Eversole, a transplanted Idaho cowboy about whom he wrote several articles. Eversole was Pyle’s perfect embodiment of the American citizen-soldier: quiet, modest, tough on the outside but caring on the inside. Above all, he was “cold and deliberate in battle,” Pyle wrote. “War is old to him and he has become almost a master of it, a senior partner in the institution of death.” It was the image that Americans back home cherished of their fighting men, and one that Pyle, more than any other correspondent, had implanted in their minds.

Of the core eight soldiers in Company E, one was killed, two were wounded, one was captured, and three others, including Eversole, were sent to the rear with bad cases of trench foot caused by the incessant rains. A few weeks later, on March 17, 1944, Pyle himself narrowly escaped death when a 500-pound bomb exploded next to the four-story waterfront villa he was sharing with other correspondents at Anzio. The blast collapsed the top floors where Pyle was quartered, and one of his fellow correspondents announced, “Well, they got Ernie.” Remarkably, Pyle escaped with only a small cut on his face. He had gotten up an instant before the explosion to look out the window; seconds later, an entire wall fell on the bed where he had been lying.

Before leaving Italy in April, Pyle made a lasting contribution to his beloved GIs by calling for combat pay for infantrymen similar to the flight pay that American airmen received while conducting missions. A month later, Congress passed legislation authorizing a 50 percent increase in pay for men engaged in frontline combat. It became known as the Ernie Pyle Bill.

In April, Pyle returned to England, where Allied forces were massing for the D-Day invasion. He was staying at the Dorchester Hotel when he got word in early May that he had won a Pulitzer Prize for his war reporting. Characteristically, he played down the honor, and when someone compared his writing with “the rugged simplicity of the Bible,” Pyle joked, “I never did think the Bible was very well written.” His own style, honed over two decades of column writing, reflected the man himself: simple, direct, down to earth, and not showy. It was the verbal reflection of his modest Midwestern upbringing. A battalion commander, not a literary critic, explained concisely Pyle’s popularity with readers: “He writes about and writes to the great, anonymous American average.” That’s who Pyle was aiming for.

On June 7, D-Day plus one, Pyle waded ashore at Omaha Beach, where thousands of American soldiers had died the day before. The beach was still “hot,” with exploding mines sending geysers of dirt and water skyward at the shoreline and sniper bullets zipping overhead. The front had moved inland a couple of miles, but Pyle chose to stay behind for a day. It was an inspired decision. While other correspondents followed the fighting, got pinned down, and had little to write about (and no way to send their observations anyway), Pyle wrote one of his most memorable columns. He went for a walk on the beach, he said—Omaha Beach.

“It was a lovely day for strolling along the seashore,” Pyle wrote. “Men were sleeping on the sand, some of them sleeping forever. Men were floating in the water, but they didn’t know they were in the water, for they were dead.” He found the high-water mark “strewn with personal gear, gear that will never be needed again, of those who fought and died to give us our entrance into Europe. Here in a jumbled row for mile on mile are soldiers’ packs. Here are socks and shoe polish, sewing kits, diaries, Bibles, and hand grenades. Here are toothbrushes and razors, and snapshots of families back home staring up at you from the sand. Here are pocket-books, metal mirrors, extra trousers, and bloody, abandoned shoes. Here are broken-handled shovels, and portable radios smashed almost beyond recognition.” He stepped around a couple pieces of driftwood, only to see with a start that they weren’t driftwood at all. “They were a soldier’s two feet,” he wrote. “The toes of his G.I. shoes pointed toward the land he had come so far to see, and which he saw so briefly.”

Once again Pyle, with his clear, unsentimental eye for detail and his understated, matter-of-fact writing style, had brought the human cost of the war back to readers on the home front, in words and images they could relate to. The most momentous invasion in history had been reduced—or expanded—to the sight of a pair of dead infantryman’s boots pointing inland toward France, and toward victory.

Pyle accompanied the 9th Division, a unit he had previously covered in North Africa, on its drive across the Cotentin Peninsula to Cherbourg. To his chagrin, he found himself besieged by starstruck GIs wherever he went. “Hey, Ernie!” they called out, as though they were meeting an old friend. They brandished rifle stocks, canteens, franc notes, letters, and clippings of his old columns for him to sign. Some asked him to pass along messages to their loved ones back home, a request he always took pains to grant. On one occasion, GIs actually interrupted a firefight with retreating Germans to crowd around him for autographs. A soldier in the 1st Armored Division explained Pyle’s appeal. “Most of these news men over here give me a healthy pain, but Ernie Pyle is different,” A. E. Bush observed in a letter to his father. “He lived and traveled right along with all of us, did the things we did, slept and sweated out all the things we did.” Pyle shrugged it off. “Soldiers like to read about themselves,” he said. Apparently, everyone else liked reading about them too: By that time, Pyle’s column was appearing in 700 daily or weekly newspapers, with an estimated readership of 30 million Americans.

The street fighting in Cherbourg was “full of sound and fury,” Pyle reported. He joined a company of riflemen on a foray up a narrow street. They crouched behind an old stone wall and then dashed one by one across an open culvert in the rain. “The men didn’t talk any,” Pyle wrote. “They just went.…They weren’t warriors. They were American boys who by mere chance of fate had wound up with guns in their hands sneaking up a death-laden street in a strange and shattered city in a faraway country in the driving rain. They were afraid, but it was beyond their power to quit. They had no choice.…And even though they aren’t warriors born to the kill, they win their battles. That’s the point.”

Pyle joined the 4th Infantry Division in late July on the breakout push codenamed Operation Cobra. On July 25, in an orchard outside Saint-Lô, he narrowly survived a mistaken dive-bombing by American planes that killed 111 GIs, including the overall commander of army ground forces, Lieutenant General Lesley J. McNair, and Associated Press photographer Bede Irvin. Another afternoon, a German shell struck a mere 20 feet behind him—“not with a crash,” he wrote, “but with a ring as though you’d struck a high-toned bell.” Other shells destroyed a forward command post just moments before he arrived. Pyle interviewed Private Tommy Clayton, who had landed at Omaha Beach and spent 37 straight days in combat. The worst part of the experience, Pyle wrote, “is just the accumulated blur, and hurting vagueness of [being] too long in the lines, the everlasting alertness, the noise and fear, the cell-by-cell exhaustion, the thinning of the ranks around you as day follows nameless day. And the constant march into eternity of your own small quota of chances for survival.” Pyle spent four days and nights on his cot, sweating out fever, stomach pains, and a deadening sense of depression. “I really don’t believe I could go through the whole thing again and keep my sanity,” he told his agent.

A month later, still aching physically and mentally, Pyle rode into Paris alongside the onrushing Free French and American forces. Curiously, the accompanying celebration left him unmoved, even disgusted. The “pent-up semi-delirium” of the newly liberated citizens gave him a “rather low opinion of Paris,” he confessed privately. “I felt as though I were living in a whorehouse—not physically but spiritually.” It was time for another Stateside furlough, which he undertook in late September.

But Pyle got little rest on his return to the United States. He passed through New York City, where his publisher was about to bring out a new book-length collection of his columns, Brave Men, and reunited with his wife in Albuquerque, New Mexico, where she was hospitalized after another failed suicide attempt. (“Are you Ernie Pyle?” she asked. He said he was. “I don’t believe it,” she replied.) He then traveled to Los Angeles and met with director William A. Wellman and actor Burgess Meredith about The Story of G.I. Joe, the film version of Here Is Your War. He paid a brief homecoming visit to Dana, Indiana, and accepted an honorary doctorate from Indiana University, from which he had dropped out in 1923. “I’ve got to go back with the boys,” he told a childhood neighbor. “I’ve got to stick with them.”

For months, readers had clamored for Pyle to report on the war in the Pacific. Although his heart was still with the soldiers in Europe, he reluctantly agreed, departing the States on New Year’s Day, 1945. He flew from San Francisco to Honolulu to Guam. Everywhere he went, he was thronged by enlisted men and civilian autograph seekers. But he felt out of place in the Pacific and thought the fighting conditions there were a good deal more comfortable than in wintry Europe. It was “like watching a slow-motion picture,” he wrote, an “endless sameness” that drove the men “pineapple crazy” with boredom. Unless you were a marine on an island invasion, a naval flier, or a sailor on an infrequently engaged ship, “the bulk of the war out here, and the bulk of the men engaged in it, are simply marking time for months on a stretch,” he wrote “They’re just doing a sort of normal, safe, drudgery job away from home.” It was, he said, “dull as dishwater.”

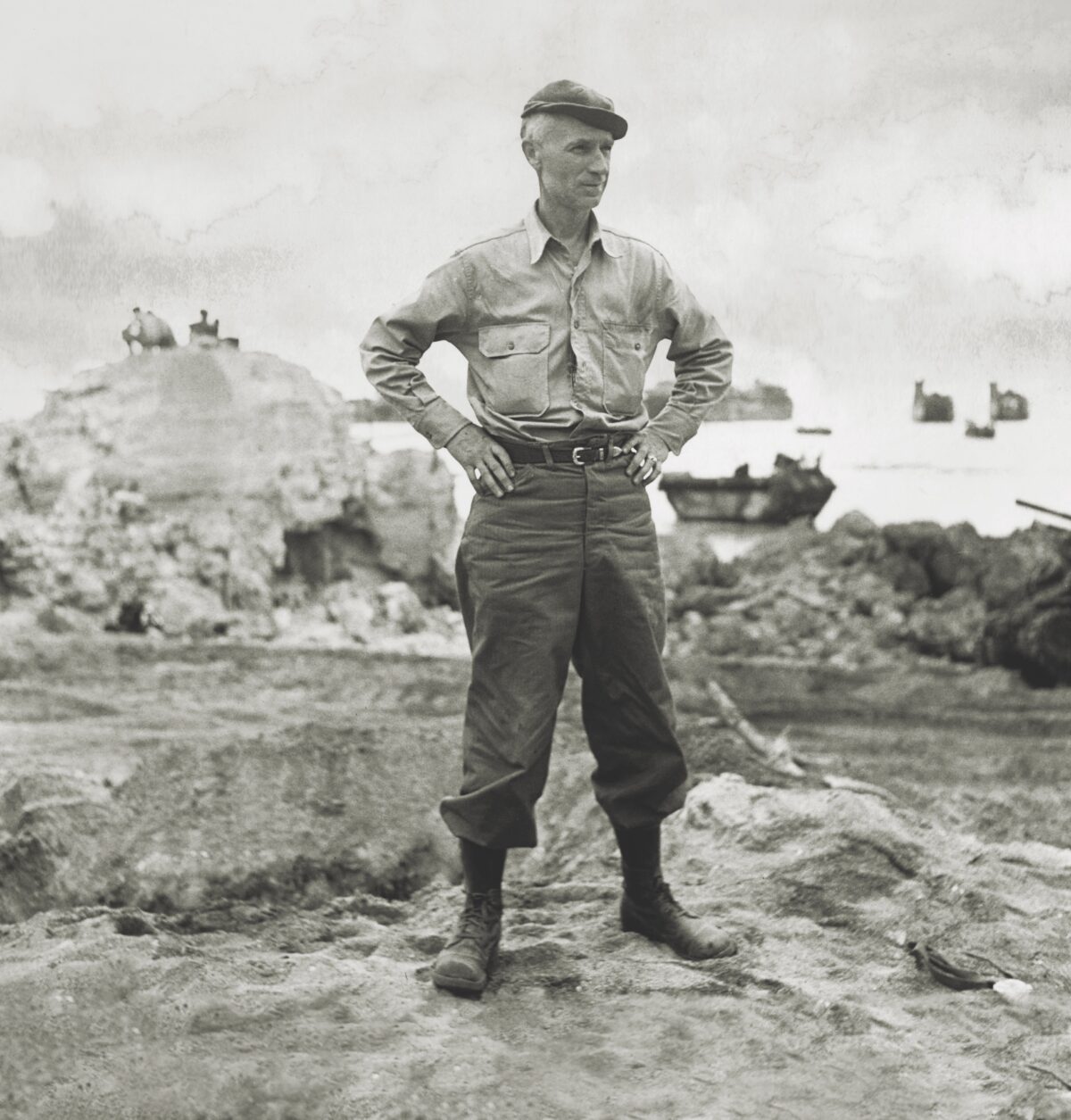

The boredom lifted when the marines and army prepared to invade Okinawa, the last Japanese-held island before the mainland. Pyle sailed to the island aboard the command ship USS Panamint. He was fighting a bad cold—an ironic ailment in balmy Pacific waters for a veteran of the snowy foxholes on North Africa and Western Europe. Privately he confided to friends, “I’m not coming back from this one.” On April 18, on a rutted dirt road on the neighboring island of Ie Shima, Pyle’s premonition came true. He died holding the battered cloth fatigue cap he had worn all through North Africa, Sicily, Italy, and France. He was buried in a temporary grave beside an infantry private and a combat engineer. At the site where he was killed, the men of the 77th Division erected a monument noting: “At this spot the 77th Infantry Division lost a buddy Ernie Pyle 18 April 1945.”

Millions of other soldiers, in Europe and the Pacific, felt the same way. General Eisenhower, who had known Pyle since the early days of the war in North Africa, spoke for all the men in his command when he said, “The GIs in Europe—and that means all of us—have lost one of our best and most understanding friends.” First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, recalling the afternoon she and Pyle shared tea, said, “I shall never forget how much I enjoyed meeting him in the White House last year, and how much I admired this frail and modest man who could endure hardships because he loved his job and our men.” And cartoonist Bill Mauldin, whose popular Willie and Joe comic strip was the visual equivalent of Pyle’s stories about the weary but persevering dogfaces, offered his own tribute: “The only difference between Pyle’s death and the death of any other good guy is that other guy is mourned by his company,” he said. “Ernie is mourned by his army.” For Ernie Pyle, that would have been more than enough.

Roy Morris Jr. is the author of nine books, including, most recently, Gertrude Stein Has Arrived: The Homecoming of a Literary Legend (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2019).

This article appears in the Autumn 2020 issue (Vol. 33, No. 1) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: ‘Ernie was one of us’