Thirty-six years after clashing over North Vietnam, two fighter pilots reconciled

On the night of April 28, 2009, two former adversaries from the Vietnam War gave a double presentation at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. Thirty-seven years earlier, they had engaged in a life-and-death struggle over North Vietnam. But on that night in 2009, former enemies Dan Cherry and Nguyen Hong My stood together as friends to recount the remarkable events that led to this unlikely moment.

The American

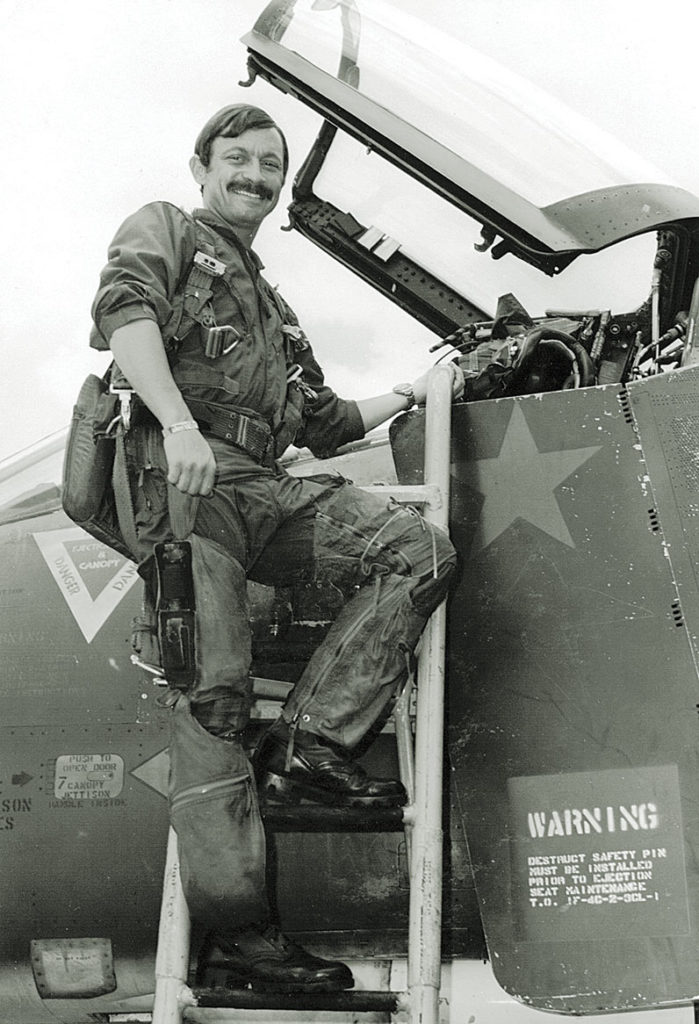

Edward Daniel Cherry, born in Youngstown, Ohio, in 1939, enlisted in the U.S. Air Force in July 1959. After completing flight training in 1965, he was assigned to the 49th Tactical Fighter Wing in Spangdahlem, West Germany, flying the Republic F-105D Thunderchief fighter-bomber. From January through August 1967, Cherry flew 100 combat missions over North Vietnam in F-105Ds with the 421st and 44th Tactical Fighter squadrons from Korat Royal Thai Air Force Base.

In 1971, after returning to the States for a stint at McConnell Air Force Base in Wichita, Kansas, as an F-105 instructor, Cherry requested a second Southeast Asian tour and reported in June to the 432nd Tactical Reconnaissance Wing at Udorn Royal Thai Air Force Base, flying the McDonnell Douglas F-4D Phantom II fighter-bomber. Over the next year he logged 185 combat missions—50 over North Vietnam.

On March 30, 1972, the North Vietnamese invaded South Vietnam in what became known as the Easter Offensive. Although the United States had withdrawn all but two of its combat brigades by then, it provided South Vietnam with critical air support. On April 6, President Richard Nixon launched Operation Linebacker, a bombing campaign against North Vietnamese industrial and transportation targets. The North Vietnamese air force responded with a formidable triad air defense combining anti-aircraft artillery, surface-to-air missiles and MiG fighters.

“On April 16, 1972,” Cherry recalled, “my name came up for a mission. I was with the 13th Tactical Fighter Squadron, and we were pretty well prepared.” His unit’s Phantoms were to escort bomb-laden strike Phantoms from the Korat air base to the Hanoi area. Capt. Frederick S. Olmsted Jr., with Capt. Stuart Maas as his weapons system officer, led the four-plane flight with Capt. Steve Cuthbert and Capt. Daniel Souell at his wing. Trailing them were Cherry, a major at the time, with Capt. Jeffrey S. Feinstein. Their wingmen were Capt. Greg Crane and Capt. Gerry Lachman. Each of the F-4Ds carried AIM-7 Sparrow radar-guided air-to-air missiles. All but Crane’s aircraft were also equipped with heat-seeking AIM-9 Sidewinders.

Recommended for you

The Mission

Departing from Udorn at 7:30 a.m., the flight orbited over Ban Ban, Laos, but the strike planes never arrived at the rendezvous point. Olmsted then led his flight north on a secondary mission to seek and destroy enemy MiGs.

As the Phantoms approached the North Vietnamese air base at Yen Bai, Maas in the lead plane detected enemy aircraft approaching from 20 miles away. Pilot Olmsted turned toward the “bandits.” As the range closed to 5 miles the Americans spotted two MiG-21s flying 5,000 feet above them. Olmsted and the other pilots turned and climbed.

“I was on the outside of the turn,” Cherry reported afterward, “so I fell behind as we turned. About halfway through the turn, my wingman called a third MiG. It was a camouflaged MiG-21 and he was at 12 o’clock level to me and climbing into position behind Olmsted’s element. The North Vietnamese had apparently been setting a trap, using the two silver MiGs for bait. The camouflaged MiG had been at low level and as we started our turn he had climbed, hoping to sandwich us between the two lead MiGs and himself. Their separation wasn’t great enough, though, and the hunter suddenly became the hunted. As we had prebriefed, we separated the flight into two elements. Olmsted continued after the two lead MiGs, and I went for the camouflaged 21. The MiG must have spotted me about the same time I rolled out of my turn and headed for him, for he turned hard left away from me and into a cloud.”

Cherry followed into the cloud and—after breaking out into the clear with his wingman, Crane—spotted the third MiG at 2 o’clock and 5,000 feet above them in a climbing turn. “I went to max afterburner and pulled around to go after him,” Cherry said. However, when he launched his two sidewinder missiles, they would not track. The MiG went into a diving spiral. As the Phantoms pursued it, Crane called, “I’m taking the lead, passing on the right.” Cherry acknowledged and rolled into the wing position.

The chase was at about 25,000 feet when Crane fired his AIM-7s. The first two malfunctioned. His third was about to strike, Cherry noted, but “at the critical point the MiG driver broke hard and the Sparrow went right by his tail without detonating.”

Crane had shot his bolt, but the dodging MiG-21 had lost speed and Cherry still had three Sparrows.

“Flying to the inside of Greg’s turn,” he reported, “I began to gain on him. While this was going on, I called Jeff in the back seat and told him, ‘I’ve got the reticle [crosshairs] on the MiG…lock him up!’ He did and the analog popped out indicating a good radar lock. It took awhile for me to pull up line abreast of Greg. When I finally did, I clamped down on the trigger again…never expecting the missile to come off. Suddenly, whoosh! That big AIM-7 smoked out in front of us.” The missile hit its target, blowing the MiG’s right wing off and sending it spinning to the left, trailing smoke and debris.

“After about two rolls the MiG driver ejected right in front of me,” Cherry reported. “I pulled off to the left to miss the chute and make sure that Jeff would see the guy and the MiG going down in flames…We must have been close to supersonic, with the afterburners cooking…and I know we weren’t more than 50 feet away from him when we passed. Even at that I got a good look at him…he had on a black flying suit, and his parachute was mostly white, with one red panel in it. I thought, ‘This is just like in the movies!’”

Within a minute of Cherry’s victory, Olmsted caught up with the two higher MiG-21s. The leader did a split-S maneuver and dove for the deck, but his wingman remained behind. Olmsted fired an AIM-7, which knocked off the MiG’s right horizontal stabilizer. His second Sparrow struck dead center, destroying the MiG in a fireball. It was Olmsted’s second victory. He had previously been credited with a MiG-21 on March 30.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

REturning home

Returning to Udorn, the Phantom crews threw a celebration. Adding to their success, an F-4D of the 432nd TRW, crewed by Capt. James C. Null and Capt. Michael D. Vahue, had knocked down a third MiG-21. It was an exceptionally good day for the 432nd TRW and a bad one for the North Vietnamese, whose records mention no pilot losses but acknowledge the loss of all three MiG-21s. As one consequence, the enemy air force restricted MiG activity south of the 20th parallel, where they would be close to U.S. forces at the Demilitarized Zone separating North and South near the 17th parallel.

By the end of 1972 the bombing campaigns of operations Linebacker I and II had resulted in American tactical victories that, like many others before them, did little to change the war’s ultimate outcome—the fall of South Vietnam on April 30, 1975. Cherry continued in his Air Force career, retiring on Dec. 1, 1988, as a brigadier general with numerous awards including the Distinguished Service Medal, the Silver Star with an oak-leaf cluster and the Distinguished Flying Cross with nine oak-leaf clusters.

After returning to his hometown of Bowling Green, Kentucky, Cherry dwelt little on his wartime experiences. Yet he wondered what had become of the enemy pilot he shot down.

In June 2004, Cherry visited the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base near Dayton, Ohio. At the nearby town of Enon, the Veterans of Foreign Wars post had taken charge of a Phantom that served with the Air Force Reserve until retired in 1989. Although painted in current gray camouflage, the plane had a red star on the intake splitter plate. Checking the plane’s serial number—66-7550—Cherry found the plane to be the very F-4D he had flown when he downed the MiG.

Although the Phantom was suffering from neglect, Cherry arranged to have it moved to a Bowling Green site being developed into the Aviation Heritage Park, devoted to military aviators from Kentucky. His F-4D was the first of several aircraft displayed there. By the time restoration was complete, Cherry commented, “It was in better shape than it was when I flew it back in April 1972.”

Finding the MiG PIlot

The rediscovery and resurrection of his Phantom led Cherry “to believe anything is possible.” He began making inquiries to see if he could identify the MiG pilot he had downed. In response, an attorney acquaintance with friends in Vietnam contacted the producers of a popular reality TV program that reunited people who had lost contact with each other. Weeks later, he heard from Thu Uyen Nguyen-Pham, producer of the show The Separation Never Seems to Have Existed (English translation), broadcast in Ho Chi Minh City, the former Saigon.

“Please write me a letter,” she said. “Tell me what you’d like to do and why.” Two weeks after Cherry sent her an email giving details of his combat, she replied: “We have found the brave MiG pilot, and we’d like you to come to Vietnam to meet him.”

Cherry consulted with the U.S. Embassy and former prisoners of war, including Lt. Col. Wallace G. Newcomb, a former F-105D pilot of the 13th TFS who had been shot down on Aug. 3, 1967, and spent the rest of the war in the notorious “Hanoi Hilton” POW prison. “I was encouraged from all sides,” Cherry said. “Wally Newcomb told me, ‘Dan, it’s just too good an opportunity for you to turn down.’”

“Thu Uyen was a delight to work with,” Cherry said. “She’d been educated in the United States and was a Fulbright scholar [an exchange program for U.S. and foreign scholars]—very professional.” When the show started at 9 p.m., April 8, 2008, he had yet to meet his former opponent, Lt. Nguyen Hong My.

“I’d never even seen a picture of Hong My,” Cherry said. “So it was very dramatic when he came in from the other side of the stage. He was an imposing figure—I thought he’d have made a good movie star. We just locked eyes immediately, sizing each other up, but he had a pleasant look on his face, and I remember he had a very firm handshake. He spoke a little English and he said, ‘I’m glad to see you’re in good health and I hope we can be friends.’”

The North Vietnamese

Nguyen Hong My, born in 1946 in Nghe An province in central North Vietnam, had joined the air force on July 1, 1965, and trained in the Soviet Union. “In 1968 I graduated from the pilot training course and went immediately back to my country to participate in the battle,” Hong My said. “My unit was the 1st Squadron of the 921st Air Force [Fighter] Regiment, nicknamed the ‘Red Star Squadron.’”

The 921st was the first unit in North Vietnam to be equipped with the MiG-21. “Some pilots had shot down Phantom jets before me, but we actually didn’t learn or have a plan worked up on how to dogfight with enemy planes,” Hong My said. “It was a case of ‘you or me.’”

North Vietnamese records credited Hong My with downing an RF-4C photoreconnaissance Phantom near the Laotian-Vietnamese border on Jan. 19, 1972, which earned him North Vietnam’s Badge for Victory. Cherry’s research revealed that Maj. Robert K. Mock and 1st Lt. John Stiles of the 14th Squadron, 432nd TRW, were downed at that exact location, but on Jan. 20. The date discrepancy possibly was a record-keeping error. Mock and Stiles, under anti-aircraft fire at the time, believed themselves victims of a 37 mm artillery shell.

Cherry is sure that Hong My’s hastily loosed R-3S missile struck the RF-4C and that the American crew, focusing on the anti-aircraft fire, never saw the missile hit.

“On Jan. 19, 1972, when I spotted John Stiles’ RF-4C,” Hong My said, “my fuel tank was very low. The air base called me back, but I still kept track on his plane and shot him down. Then I flew back to Tho Xuan air base, near Thanh Hua city. … Just after I landed, my plane ran out of fuel and shut off.”

Hong My, like Cherry, wondered what became of his opponents. As it turned out, Mock and Stiles were safely rescued by helicopter.

Almost three months later, Hong My had his fateful encounter with Cherry when he attacked the American Phantoms. In the North Vietnamese air force, he said, “we were taught to never run away from the enemy, both in the academy and in combat—to do so showed bad character. We were trained in how to evade most of your missiles.”

The dogfight from the other cockpit

Hong My explained the events of the aerial duel as he saw them: “On April 16, 1972, there were only two planes in my flight. I tried to evade your missiles and dodged five of them, but finally my plane took a hit from your missile and was shot down. I just took to my parachute—I had no time to think what was going on. I just tried to get out of the plane ASAP. Two of my arms were broken, and I was badly injured on my back. I spent a long time, six months, in the hospital. Four times I underwent surgery. The doctor said my health was not good, that I could not fly anymore.”

Nevertheless, he returned to service.

“In 1974, I got out of the Vietnam Air Force,” Hong My said. “As a pilot it was difficult to find a job. I went to school to take economics and foreign languages. After graduation I worked for the Vietnam Insurance Company. I retired in 2006 and cannot get any job now. But I’m busy enough working as a grandparent!”

Fast Friends

After the TV show in Ho Chi Minh City, the former opponents continued to talk with each other. “Being from Kentucky, I’d brought him a gift—a little bottle of Maker’s Mark [bourbon whiskey],” Cherry said. “As we got to know each other more, the chemistry continued to build. I saw two medals that he proudly wore on his chest—his First Class Wings, presented by Ho Chi Minh, and a badge for his aerial victory.

“We became instant celebrities, reliving the combat on top of the Majestic Hotel in downtown Saigon. At one point, he pointed to my hand and asked, ‘You shoot your missile like this or like that?’ meaning thumb or forefinger. When I showed him, he spanked my trigger finger with a hearty laugh…At the end, he said, ‘I want you to come to my home in Hanoi.’

“It was very surreal as we flew on Vietnam Air, over the same country I flew countless missions over. I stayed in the Metropole Hotel, within walking distance of Hong My’s home. We took a wonderful stroll through the streets of Hanoi, past the old French opera house. At his house I met his daughter, Giang, and his son, Quan. Hong My then let me hold his grandson, little Duc, who was just having his first birthday.

A familiar Face

“The next day we took a tour of Hanoi, all the museums. The exhibits at the war museum—including a photo of my squadron, the 13th TFS—were a sad reminder of the war. But sadder still was the Maison Centrale, the ‘Hanoi Hilton.’ The French had originally used it for political prisoners, and it was a horrible place, now a museum. Hong My turned somber as we went through the exhibits, and he asked me, ‘You have a friend in here?’ Just then my eyes fell on a picture of Col. John Flynn, and I answered, ‘Yes, I did.’”

Flynn, an acquaintance of Cherry’s in the 49th TFW at Spangdahlen Air Base, was vice commander of the 388th TFW at Korat when his F-105D was brought down by a ground missile on Oct. 27, 1967. Flynn was the highest-ranking American POW in North Vietnam until his release on March 14, 1973.

When Hong My learned that his new friend personally knew POWs at the prison, “he dropped his head and walked away, to leave me to my thoughts,” Cherry said. “When I came outside, he put his arm around my shoulder.”

Cherry added: “Our POWs don’t hold anything against the pilots who fought us. They do still hold something against the government and the prison administrators.”

After returning to the United States, Cherry wrote a short account of his odyssey in a book, My Enemy, My Friend, published in February 2009. The end of that book was not the end of the story, however.

COming to America

Cherry reciprocated Hong My’s hospitality by inviting him and his son to visit Bowling Green. On April 16, 2009, exactly 37 years to the day after the aerial combat in Vietnam, Hong My and Quan “sat in the cockpit of 550, which gave him possibly the unique distinction of being the only vanquished fighter pilot to sit in the fighter that actually shot him down,” Cherry said.

Cherry flew Hong My in his Cessna 172 to Frankfort. “I cried when I was at the Kentucky Vietnam Memorial,” the Vietnamese veteran said. “Seeing the names of all the American soldiers who died in the war made me think too of all my friends.”

Hong My wanted to know if the airmen he had shot down were still alive. Tragically, pilot Mock had died in a car wreck in Colorado just two months before Cherry began his research. The navigator, Stiles, lived in North Carolina. “We had a double full circle as Hong My visited Stiles and met his family, and they too became friends,” Cherry said.

On April 26, Cherry, Stiles and Hong My went to Washington. “I think a lot about this visit,” Hong My later remarked. “I would like to see my country cooperate to bring back the remains of all soldiers missing in the war. I had two unforgettable things during my visit. First, the governor ‘promoted’ me to be an honorary Kentucky Colonel! The other was when I met John Stiles, to have dinner with him. I felt very happy.”

The two pilots were able to recount the story of their shared experience at the National Air and Space Museum. At the end, Cherry concluded: “I hope in its way this helps Vietnam War veterans on both sides to find some closure and that it will be an inspiration to our two countries. If there is one thing I learned from this experience, it is that holding grudges is really futile.”

“To me,” Hong My remarked, “the joy and the miracle of it all is, here we are, me, Dan Cherry and John Stiles, still alive and meeting together in Washington, D.C.” V

Jon Guttman is research director for Vietnam magazine. Cherry’s book, ‘My Enemy, My Friend,’ written with Fran Erickson, and additional information are available at aviationheritagepark.com.

This article appeared in the April 2021 issue of Vietnam magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.