“I wish I were triplets,” Ellen Swallow said as a newly arrived but belated Vassar College undergraduate, dreaming at 25 of making up for lost time.

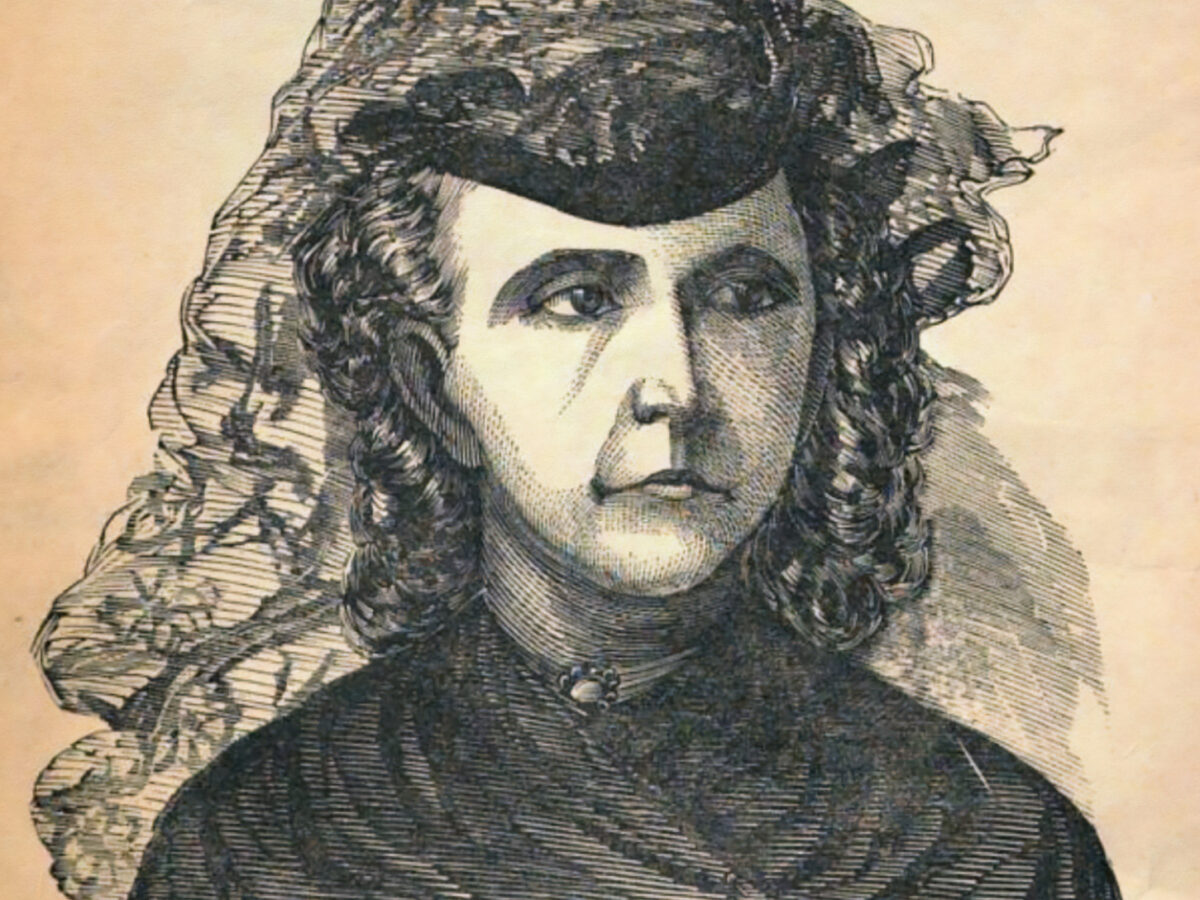

By the time she died at 68 of heart disease in 1911, she had built a career as a chemist and engineer that smashed gender barriers and would have filled a half-dozen résumés. Slight, bright-eyed, and dark-browed, with a quizzical, crooked expression, Ellen Swallow was a one-woman parade of firsts: first female student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, first female fellow of the American Association of Mining and Metallurgy, first female professor at MIT.

She invented the word “euthenics,” meaning the science of environmental management. When eugenics — controlled breeding of humans — was all the rage as a path to better living, Swallow posited a holistic understanding of environmental conditions as the key to health. Colleagues credited her with establishing the academic discipline of home economics, a line of study that helped households run healthfully and efficiently. Swallow founded what became the American Association for University Women, as well as a seaside lab that evolved into the prestigious Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Early Promise

In childhood, Swallow displayed unmistakable talent despite physical frailty. Raised in Dunstable, Massachusetts, by schoolteacher parents who kept a farm, she grew up surrounded by books. When she was 17, her father opened a store in Westford so his daughter could attend school there. Two years later, he moved the store to Littleton, where Ellen served as postmistress, sharing periodicals and discussing the issues of the day with customers. In 1865, at age 23, she took a position teaching children in Worcester. Observing female friends’ unhappy marriages, she doubted that she would wed.

“Pray for me, dear Annie, that my life may not be entirely in vain, that I may be of some use in this sinful world,” she wrote to a cousin. “I feel sometimes as though I would be glad to leave it, the ties that bind me to earth at times seem very slight.”

She found purpose in 1868 when she tested into the junior class at Vassar — then the only American college for women. Diving into laboratory science, she found a mentor in Maria Mitchell, helping the pioneering astronomer record meteorological observations. Deft fingers that in girlhood had won her an award for embroidery made her a gifted and meticulous technician. At her dormitory, she chose a fifth-floor room, so she could watch the sky and study uninterrupted. Curiosity and a quantitative bent—she counted the steps to her room and calculated the miles she walked on campus — came to define her life.

Recommended for you

Mastering MIT

Graduating from Vassar in 1870, Swallow applied to the new Massachusetts Institute of Technology, which as yet had admitted no women. Enrolled as a “special student” over certain instructors’ objections, she decided utility could trump sexism. Offering fellow students help ranging from tutoring to mending, Swallow said later, she learned “where the powder magazines were situated, and carefully avoided the vicinity, but did not put out my candle. And now I begin to see that my little light has had its effect. An extra covering is thrown over the fiery material when I am around so that I can come nearer, and I feel that I’ve conquered.”

At all times operating with calculated determination, Swallow was inventive. Frustrated that women’s clothing lacked pockets, she sewed a pouch she suspended from a belt. She recognized that to progress women had to be in shape.

“Nowadays the last card they can trump up against us is that we are not physically equal to what we try to do,” she said.

To avoid unwelcome attention or criticism, she counseled her striving sisters to go “unremarked in a crowd” — even though her own talents and discipline consistently stood her apart.

Robert Richards, her geology and minerology professor, noted her skill.

“She came near to being one of those immortals who have identified new elements in the earth’s crust,” he said.

In time, an instructor who had balked at even letting Swallow into MIT hired her for a water quality project with landmark results. Boston and adjacent towns were spewing waste and sewage into waterways, utterly unregulated. The project showed Swallow firsthand what industry did to water — and the need for rules to prevent air and water pollution and adulteration of food.

Fruitful Middle Years

In 1875, two years after receiving a chemistry degree from MIT, Ellen Swallow married Robert Richards, now head of the institute’s mining engineering department. Buying a house in Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts, they enlarged the windows and swapped a coal furnace for a cleaner-burning gas model. Daily, the two walked or bicycled together.

Swallow Richards’s middle years were a catalog of achievements expanding scientific education for women and improving the public health. In 1875, while teaching chemistry at MIT for no pay, she raised money to convert a garage into a laboratory for female special students. Not until 1883 did the institution enroll women as a matter of course. In 1884, Swallow Richards was hired as professor of sanitary chemistry; during her lifetime, she was MIT’s only paid female instructor.

Inventing Health Food and Fighting Dewey

The state of Massachusetts hired her as a consultant. To aid women struggling to educate themselves, she created and ran a correspondence course. She wrote household management manuals The Chemistry of Cooking and Cleaning, The Science of Nutrition, Home Sanitation, and Food Materials and Their Adulteration. Her endeavors foreshadowed the test kitchen and the health food restaurant. An 1890 project sought to nourish the impoverished by distributing scientifically balanced meals that recipients did not always find palatable. Swallow Richards had more success with Rumsford Kitchen. That facility, at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, offered healthy meals, recipes and nutritional education. A Swallow Richards venture delivered healthy lunches to high school students in Boston who until then had been buying food, typically sweets, from janitors or going hungry. This effort expanded into nutrition programs at hospitals and prisons.

Swallow Richards laid the groundwork for a revolution in understanding the interaction of nutrition, environment and health. She brought a scientific perspective to household life: how to cook healthy meals, the importance of ventilation, the need for clean air and water. She and her allies advocated on behalf of reforms in the home and in the factory. Recognizing housekeeping to be a set of important skills, in 1909 Swallow Richards helped found a body dedicated to household management. Her intensely scientific orientation led to debate with co-founder Melvil Dewey, creator of the Dewey decimal library system, over the organization’s name. Dewey prevailed, and so emerged the American Home Economics Association, in 1994 renamed the American Association of Family and Consumer Science.

Improving Vassar

In 1894, convinced Vassar should be an exemplar, she used her trusteeship to help devise the school’s first sewage system, retiring the practice of using a Poughkeepsie creek as a toilet drain. The initial estimate for the job was $37,000; the version Swallow Richards implemented cost $7,500.

“The quality of life depends on the ability of society to teach its members how to live in harmony with their environment — defined first as the family, then with the community, then with the world and its resources,” she said.

Claims that women running households needed no higher education irked her.

“’What do you expect this will do in the kitchen?’ I have never succeeded in banishing the ring of that question from my ears. Indeed, it has been repeated in other forms so many times since that I have had little opportunity to forget,” she said. “Can a housekeeper know too much of the effect of fresh air on the human system, of the danger of sewer gas, of foul water?”

All her life, she pressed on.

“I ask nothing more, only longer days or quicker memory,” she said. There is so much to do.” In her 1902 book Euthenics, Ellen Swallow Richards wrote, “If the State is to have good citizens it must provide for the teaching of the essentials to a generation that will become the wiser mothers and fathers of the next.”

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.