Two ships and their captains battle fate in the grip of an infamous typhoon

The waves in the Philippine Sea were monstrous, as winds roared at up to 140 miles per hour. Visibility dropped to near zero. On the dark, gray morning of December 18, 1944, Henry Plage, skipper of the destroyer escort USS Tabberer, and Jim Marks, captain of destroyer USS Hull, found themselves fighting for the very survival of their crews and ships. As the sea surged, Tabberer and Hull rolled and bucked, trembled and shook.

To Plage, the 60-foot waves “looked like vertical mountains bearing down on us.” When one wave hit, the ships’ bows would rise high out of the water, then smash down heavily, spume reaching beyond the bridge. Now and then, a wave would strike broadside and push the ships over at an angle—sometimes as far as 72 degrees. Slowly the vessels would right themselves, only to be jolted in the opposite direction by the next wave. Before the week was out, these two 29-year-old officers would be subjected to an ordeal that would have tested the mettle of even the most seasoned, battle-hardened captains in the U.S. Navy.

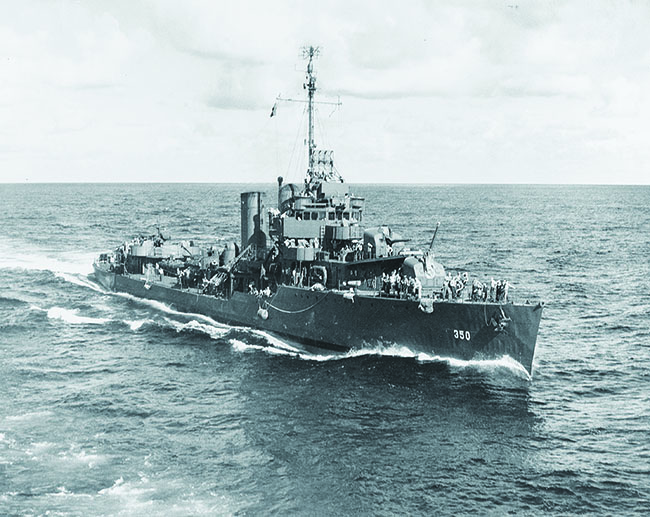

Tabberer and Hull had drawn the unglamorous task of protecting the 24 oil tankers that were part of the 170-some vessels composing Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey’s Third Fleet during its air support operations on December 14 off the coast of the Philippines. There the striking arm of Halsey’s fleet had conducted three days of successful raids against Japanese installations on Luzon. The operation had depleted many of the ships’ fuel supplies, especially among the dozens of escort vessels. So on the fourth day, December 17, the force retired to the east for refueling before engaging another round of attacks.

It was on that day when the Philippine Sea began to churn and blow, forcing the suspension of oiling activities. Halsey had unknowingly sailed his armada into the maw of a deadly category-four typhoon the navy later named “Cobra.”

AN UNFETTERED FLOW OF OIL was critical to the strategic success of Halsey’s campaign in the South Pacific. All his ships—from battleships and carriers to stubby ocean-going tugs—had a voracious thirst for fuel, and so a train of two dozen fleet oilers followed in the task force’s wake.

The refueling process itself was an intricate dance between two ships, the receiver and the oiler, cruising in tight formation fewer than 50 yards apart while connected by a complex web of booms, lines, and fuel hoses. In the best of times, at-sea refueling required precision seamanship. In storm waters, with the ships rolling and yawing, demands on the captains’ skills rose exponentially. Seeking calmer waters, Halsey changed the fleet’s course four times in fewer than three hours to no avail as the weather worsened. Finally, refueling was rescheduled for the following morning, Monday, December 18.

There was widespread confusion among the task force’s commanding officers about the nature of the weather they were sailing into. This was in part due to a weather map released on December 17 at 1 p.m. by Halsey’s chief meteorologist, Commander George F. Kosco, who was aboard Halsey’s flagship, the USS New Jersey. Based on scanty data, Kosco said the map indicated a “tropical disturbance” 600 miles to the east and “moving north-northwest at 12 to 18 miles per hour” away from the Third Fleet. The ever-aggressive Halsey had a tight schedule of strikes to meet and he was loath to let a little storm slow him down. What neither man knew was that this mere “disturbance” was in fact a full-blown typhoon roiling the Pacific barely 200 miles east-southeast and nearing the peak of its destructive powers.

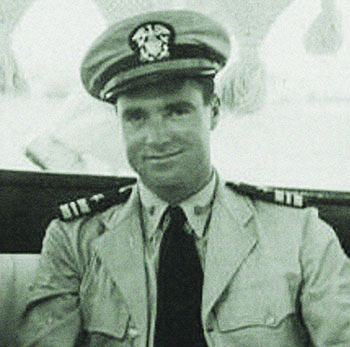

Caught in the brewing storm was Tabberer’s captain, Lieutenant Commander Henry L. Plage. A reservist from Atlanta, Georgia, Plage was tall, thin, and thick-browed. He had majored in industrial management at Georgia Tech, where he was a championship swimmer and a star cadet in the Navy Reserve Officers’ Training Corps, excelling in seamanship. Upon graduating in 1937, Plage was commissioned an ensign in the Navy Reserve. He married that summer, took a job as an insurance adjuster, and moved to Florida.

In January 1941, sensing war might be on the horizon, Plage asked the navy to activate him. They did, but to his disappointment they anchored him to a desk. Then in May 1942, Plage was given the chance to get into the shooting war when he was made commanding officer of the Panama Canal-based subchaser PC-464. Eighteen months later, he took control of the destroyer escort USS Donaldson. As soon as that ship arrived in the Marshall Islands at the beginning of March 1944, Plage was handed his third command, USS Tabberer. Then fitting out at a Houston, Texas, shipyard, the ship was a John C. Butler-class destroyer escort, 306 feet long, with a crew of 215.

Tabberer, or “Tabby,” was commissioned on May 23. After a round of sea trials, it made its way to Pearl Harbor, arriving there in early September. Plage used the 10-week cruise to mold his crew. There was a lot of molding to do; two-thirds of the ship’s complement—officers and enlisted men, many still in their teens—had never been to sea. By the time Tabby reached Hawaii, Plage had drummed the basics of sailing a ship into their heads. Over the following weeks, the captain concentrated on teaching the finer points of combat at sea, with rigorous antisubmarine and gunnery drills. During this intense period, the skipper earned his crew’s respect with firm but fair—sometimes almost paternal—leadership. In October 1944, the ship sailed to the navy’s advance support base at Ulithi Atoll to join Admiral Halsey’s Third Fleet.

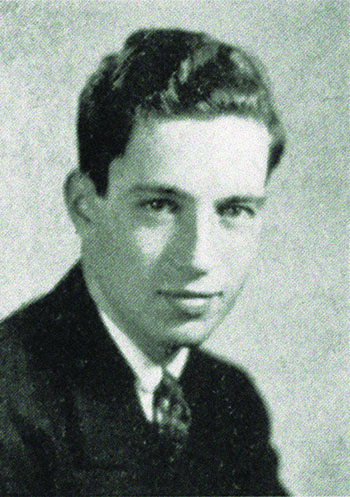

Hull’s commander, James Alexander Marks, hailed from Washington, DC, where his father was a senior Treasury Department official. Short and slim, Marks was his high school class valedictorian and, at Annapolis, played a mean swing clarinet in the Naval Academy’s jazz band. He graduated in 1938, ranking near the top of his class. After a year as an engineering officer aboard the battleship Colorado, Marks joined the destroyer USS Trippe. On October 2, 1944, after nearly four years of convoy duty in the North Atlantic, he was finally given command of his own ship.

The USS Hull, commissioned in 1935, was one of eight Farragut-class destroyers. It was 341 feet long with a complement of 260 men. But Marks’s style of command proved a stark contrast to the congenial and popular captain he succeeded. One of his first acts was to ban fraternization between officers and enlisted men. And, decreeing there would be no profanity aboard his ship, the rookie captain punished sailors for using what he deemed “foul language.” His crew chafed at his draconian rules, earning Marks a reputation as an unyielding martinet who took little interest in the welfare of his men. He also proved inept at handling his ship, making scores of elementary piloting mistakes that worried the crew. Their lack of confidence grew so acute that when the Hull departed for Hawaii in mid-October, 20 seamen jumped ship, refusing to sail with Marks.

DECEMBER WEATHER in the western Pacific can be tempestuous—and so it was throughout the night of the 17th. But conditions grew even worse the next morning. “The waves were so great and the wind was such a high velocity that the rain would just about cut your skin, it was coming down with such force,” recalled Pat Douhan, a sonarman aboard Hull.

Over on the New Jersey, Bull Halsey and George Kosco still didn’t know for sure where the storm was or if it was more than just a tropical disturbance. At about 5 a.m. Halsey, at Kosco’s recommendation, ordered the Third Fleet to change course southeast to avoid the maelstrom—but that was exactly where Cobra lay ready to strike.

Tabby’s commander Henry Plage watched with concern as the ship’s barometer dropped like a lead weight. Taking it as a warning that the storm center was near, he ordered his

crew to batten down all hatches and add ballast to the ship by pumping seawater into empty fuel tanks to stabilize it. Captain Marks, on the other hand, had decided that ballasting Hull was inadvisable. As he later said, “The ship was riding satisfactorily.”

Around 8 a.m., the Talk-Between-Ships (TBS) radio circuit came alive. Light carrier Monterey: “All planes on my hangar deck on fire.” Escort carrier Cape Esperance: “Thirty-two aircraft jettisoned over the side by wind force and roll.” Rudyerd Bay reported it was dead in the water. Kwajalein lost steering control. Flagship New Jersey, destroyer Dewey, and Tabberer all narrowly avoided collisions with ships that loomed suddenly out of the mists.

It wasn’t until 10 a.m. that Kosco finally concluded that the fleet was about to encounter a typhoon. By then it was too late. Throughout the morning, plaintive calls of “man overboard” punctuated ships’ reports. Many vessels found themselves “locked in irons”—drifting helplessly in deep troughs of waves, unable to steer themselves out. That afternoon, the typhoon carried Tabby’s mainmast away along with its radar and radio antennas, leaving the ship deaf, dumb, and blind.

AS COBRA COILED AROUND THE FLEET, Jim Marks on Hull grew cautious, then obstinate, then paralyzed. To veteran quartermaster Archie DeRyckere, the captain did not seem to be “fully in command.” When 24-year-old Boatswain’s Mate First Class John Ray Schultz suggested he take a detail to cut away the ship’s dangling whaleboat, Marks curtly replied, “permission denied” and ordered him off the bridge. Shortly after, as Hull rolled side to side, the whaleboat broke loose, smashed into a dozen deckhands, and swept them into the sea.

Schultz continued to confront Marks, who had wedged himself into a corner of the wheelhouse. The boatswain wanted the skipper to tell his men to don their life jackets, which he had sagely equipped with whistles and small flashlights. Marks shouted, “What are you trying to do, panic my crew?” The disgusted young mate took matters into his own hands, picked up the microphone and announced, “Man your life jackets.” When an officer on the bridge said he didn’t have one, the sailor looked over at Marks and said, within earshot, “Why don’

t you ask the captain for his? He’s supposed to go down with the ship anyway.”

Sometime after 11 a.m. Marks ordered a course change. Lieutenant Greil Gerstley, the ship’s cool-headed executive officer, was standing next to the helmsman. An experienced ship handler, Gerstley warned the captain, “Don’t turn the ship!” But it was too late. The destroyer dropped into a trough, was caught “in irons,” and was more than ever in the grip of Cobra.

Schultz was furious at Marks. In the words of Gerstley’s son, writer Greil Marcus, the boatswain “begged my father—who was trusted as the captain was not, admired as the captain was reviled—to seize the ship: to place the captain under arrest, take command, and save the ship; in other words, to lead a mutiny.” Marks ignored Schultz’s plea. Gerstley briefly considered taking action, but then said to the boatswain, “If I take over and save the ship, he’ll say it was mutiny. If we don’t all drown, he’ll have me tried and hanged.” And with that the ship’s fate was sealed.

Just after noon on December 18, USS Hull keeled over one degree too far, and instead of righting itself, stayed on its side in the convulsing sea and slowly began to sink. Every man who could jumped or dove into the water. A hundred or more doomed sailors were trapped below decks. Captain Marks got off safely. Lieutenant Gerstley did not.

Surviving Hull sailors floated singly or in small groups. A few clung to life rafts. As the hulk went down, the powerful suction pulled men down with it. The waves and winds made it difficult treading. “A big wave just beats the tar out of you. It threw me around like a ball in a court,” recalled Schultz. “It’s so big out there, and it’s so scary,” said sonarman Pat Douhan, “I was by myself in the middle of the South Pacific wondering what’s going to happen next. Am I ever going to be saved?”

With the coming of nightfall, the storm began to abate and the wild Philippine Sea began to calm. Little pinpoints of light and whistle tweets pierced the darkness as Hull’s men sought their crewmates. It was a difficult night for the survivors. Some just gave up and drifted off to die. At sunup, a new threat appeared. “The first thing we saw that next morning was dorsal fins,” said Douhan. One group of men watched in horror as a 12-foot shark attacked first one man, then a second. Archie DeRyckere remembered thinking, “God…first you sink my ship, then you have me swimming in this ocean all night, and now you’re going to feed me to the sharks. That just ain’t right.”

TABBERER STAYED AFLOAT because of Henry Plage’s expert seamanship. The precautions he had taken the previous day to batten down hatches and add ballast made the Tabby all the more stable in the face of Cobra.

At 9:50 p.m. on December 18, Chief Radioman Ralph E. Tucker saw a flicker of light on the sea. “Man overboard!” he shouted. Plage recalled, “With the waves so high you could only see that man’s little flashlight maybe one second out of every ten.” But it was enough for the ship’s searchlights to spot him. The skipper deftly maneuvered Tabby through the rollers to where his crew could toss the sailor a line and haul him aboard.

Taken to the sickbay, Quartermaster Au-gust Lindquist told Commander Plage that his ship, the Hull, had sunk at the height of the typhoon and that there were more men floating in the waters nearby. Plage directed his crew to watch for lights and listen for whistles. Their efforts soon paid off. In the space of 90 minutes, Tabby picked up 10 more of Hull’s crew and, by dawn the next day, had pulled in another eight, including Jim Marks. By sundown, the ship had rescued 41 Hull survivors.

Early the next morning, December 20, the escort carrier Rudyerd Bay relieved Tabby of rescue operations so the destroyer escort could proceed to Ulithi Atoll for repairs. As Plage shaped his course east, he saw still more men floating in the sea, and by noon had recovered 14, not from Hull, but from the destroyer USS Spence, which had also succumbed to Cobra. When Tabby finally turned toward Ulithi, it was carrying 55 lucky and grateful men. During the voyage, Captain Plage posted a memo to all hands praising their performance. He closed with, “I admire the fine job you have done, [and] I am proud of having the opportunity to serve with you on the Tabberer.”

The losses to Bull Halsey’s Third Fleet were staggering. Cobra had sunk three ships—destroyers Hull, Spence, and Monaghan—and damaged 29 more, some so severely they were forced to return to Pearl Harbor for repairs. One hundred forty-six aircraft were de-stroyed or lost overboard and 790 sailors perished. Despite fleet-wide rescue efforts, only 94 men were pulled alive from the sea.

On December 25, shortly after Halsey’s fleet reached Ulithi, the navy convened an official court of inquiry to “investigate the causes of loss and damage, and the responsibility for them.” The court wanted to know how this disaster could have happened. Admiral Halsey testified that he “did not have timely warning” of the approaching storm. Was the navy’s weather service adequate? “It was nonexistent,” Halsey replied. Chief meteorologist George Kosco was called before the board twice to explain his forecasting blunders. He admitted underestimating the strength of Cobra, basing his prediction on historical data about regional storms rather than relying upon current local observations.

On the fourth day of the proceedings, Jim Marks read his statement to the court in front of his ship’s surviving men. “In endeavoring to alleviate the heavy rolling of the ship, I tried every possible combination of rudder and engine, with little avail. It was apparent that no matter what was done, the ship was being blown bodily before the wind and sea.” He told the board that the high winds “laid the ship steadily over on her starboard side and held her down in the water.” After completing his statement, the court asked Marks if he had any complaints to make about the conduct of his crew. “No,” he said. “The performance of duty was at all times highly creditable.”

The survivors were asked the same question of their captain’s conduct. “No,” they responded. The insolence displayed by Boatswain’s Mate First Class John Ray Schultz in the wheelhouse and the talk of mutiny with Lieutenant Greil Gerstley was never mentioned.

After hearing from dozens of witnesses, the court released its report on January 3, 1945, finding that the “Preponderance of responsibility falls on Commander Third Fleet, Admiral William F. Halsey.” Halsey’s only punishment was a slap on the wrist for “errors in judgment.” Chief meteorologist George Kosco was likewise mildly reprimanded.

On December 29, 1944, Halsey conferred upon Henry L. Plage the Legion of Merit for the skipper’s “courageous leadership and excellent seamanship through treacherous and storm-swept seas.” Later that day, Halsey led his decimated fleet out of Ulithi toward its first combat sortie since his encounter with Cobra. The Third Fleet had been out of action for 18 days.

TYPHOON COBRA EMERGED VICTORIOUS in its lopsided tangle with Bull Halsey. It was, said Commander in Chief, Pacific, Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, the “greatest loss we have taken in the Pacific since the First Battle of Savo Island” in August 1942. In a February 1945 letter to all his forces outlining his views on the disaster, Nimitz wrote: “The important thing is for it to never happen again.”

Then in June 1945 Halsey sailed the Third Fleet into Typhoon Viper.

This time losses were not nearly as great—no ships were sunk and only six sailors died—but it appeared that the admiral had failed to heed Nimitz’s cautionary warnings.

A second court of inquiry found Halsey again shouldered primary responsibility and recommended he be relieved. He was not; he fought on until the end of the war and retired as a five-star fleet admiral in 1947.

As a direct result of these naval battles against superior natural forces, in mid-1945 the navy expanded its Pacific weather forecasting capabilities and established the Typhoon Tracking Center on Guam. Now called the Joint Typhoon Warning Center and headquartered at Pearl Harbor, the unit combines data from weather satellites, hunter aircraft, and computer models to provide warnings of cyclonic events for the greater Pacific and Indian Ocean areas. The center is a lasting legacy of Bull Halsey’s deadly encounters with Cobra and Viper.

On May 19, 1986, Cobra claimed one more victim. After suffering for years from the effects of trauma following the loss of his ship, Captain James Alexander Marks, then retired from the navy, shot himself in the living room of his Florida home. He was 71. ✯