By January 14, 1945, I had been in England with the U.S. Eighth Air Force for more than seven months, piloting a B-24 heavy bomber. I had completed 35 bombing missions over France and Germany—at that time, a tour of duty—and was set to return to the States for a 30-day furlough. I wrote to my fiancée, Betty Sue Nunn, that for me the war was over and I was coming home to Pittsburgh for the wedding we had planned.

In the meantime, I learned that if I took a second tour without returning to the States, the tour requirement would be cut in half and I could then expect a permanent stateside assignment. The decision became easier when I was offered the chance to join a P-51 fighter squadron. The Mustang—the best single-engine propeller aircraft of all time—was every pilot’s dream. I carefully prepared a follow-up letter to Betts and my parents explaining that I had elected to stay in Europe, and arrived at my new station at Steeple Morden Airfield near Cambridge. First Lieutenant R. A. Gray reporting for duty.

During the next several weeks, I flew nearly every day, practicing landing, formation, and getting some gunnery practice. Several bomber escort missions over Germany followed. Then came April 4, 1945.

Like the others, this mission was in escort of heavy bombers. We climbed out over the Channel and proceeded toward Germany. My flight dropped down to observe one of the bombers’ targets: an airfield about 100 miles north of Berlin. We circled at low altitude. As we completed the first pass, 20mm guns mounted in flak towers surrounding the field began firing on us. Since my plane was on the inside of the circle, I became the principal target.

My immediate reaction was to make a diving pass across the field to spray some .50-caliber bullets toward one of the towers. As I made my pass, about 20 feet above the runway, I saw several Heinkel 111 bombers off to the side and, in my anxiety to score victories, forgot the tower. That was a big mistake.

All of a sudden everything went black: oil was pouring from my engine onto the windshield. Once I had gained a little altitude, I saw that about three feet of my left wing had been shot away. I decided to stay at low altitude, search for a clear spot to crash-land, and take the consequences. Reacting instinctively, I redirected toward a clearing and tipped up vertically to slip between bordering trees. Because most of our training was done with a left-hand landing pattern, I instinctively dropped the left wing. That, too, was a mistake: with the missing tip, the wing didn’t have normal lift, and I speculate that I slid vertically and caught it on the nearest trees.

I’m forced to speculate, for I have no memory of what happened then or what I did. My first memory is of coming awake curled in the fetal position under some shrubbery, my pistol clutched in my arms. My head and right leg hurt like hell, my shirt was soaked with blood, and my vision was blurred and faint. I started walking through the woods, but my strength was ebbing rapidly; after only about 1,000 yards, I lay down again. When I reawakened, I found my vision had cleared up, but I had no sight in my right eye. My nose had several broken bones, and there was a large laceration in the middle of my forehead and possibly a splintered bone in my right leg.

I resumed walking until I came upon a dirt road. I furtively looked out and saw a horse-drawn wagon approaching me. I can only guess what I must have looked like to this farmer and his son as I stood there, bloodied in my U.S. uniform, my .45-caliber automatic pistol in clear view. By my gestures, they understood that I did not mean to harm them. They helped me onto the wagon and drove me to their farm a short way down the road. The farmer and son went into the house and a few moments later came out accompanied by the farmer’s wife. The son trotted off down the road and the wife approached me with a glass of water and a white shirt that she tore into strips for bandages.

I still had my gun. Our general instructions were to protect ourselves from civilians and give ourselves up to the military. This was on the supposition that most of the German military—like ourselves—had had enough fighting, whereas civilians had only thoughts of revenge for the loss of their families and possessions at the hands of Allied airmen. But there was nothing but concern for me being shown by this family, so I drank some water, then dampened a strip of cloth and began wiping the blood from my face and leg. The woman helped me bandage my head and the bridge of my nose. We tried to converse, but lacked any ability to do so in each other’s language.

In perhaps an hour, the son returned with a Luftwaffe soldier wheeling a bicycle. The soldier—a corporal, I think—also spoke no English; he motioned for me to get up on the seat, which I did, and he started pushing me down the lane. We went for perhaps 10 or 15 minutes and stopped to rest. He lit cigarettes for both of us. We continued on this way for the next hour, pushing and resting. After the second rest stop, I decided I was reasonably safe and gave him my gun and ammo clips. He seemed relieved and smiled at me pleasantly.

We finally reached an air base—the one I had strafed. Several officers and enlisted men came to interrogate me. Their first statement was: “For you the war is over.” Funny, but that was what I had written Betts after my first tour was finished. For about the next hour, they questioned me. I continued to respond with my name, rank, and serial number. Then I got quite a surprise when they pulled out a map of Steeple Morden Airfield. They recited my squadron number, group number, and showed where my plane was parked. They named my group commander, squadron commander, operations officer, and even my supply officer. I must have shown no recognition of that last man for they quickly responded, “You probably don’t know him since he is very new.”

I lay dozing the next morning when the corporal came in with another soldier who spoke a little English. He told me it was his duty to take me to a prison camp. I made eating motions and he understood, so we first went to the mess hall. I followed him down the chow line and was served just like the rest of the troops. Well, almost. When the cook looked up at me standing in line with my leather jacket emblazoned with an American flag, he scowled and scooped some of the hash browns back off my plate.

The corporal and I then boarded a truck and drove several hours to a second air base where I was handed over to another Luftwaffe soldier. This new guard and companion spoke a few words of English and French. He took me to his room in the barracks, which he shared with another soldier. He brought in chairs and put them together to make a bed. In the middle of the night my guard’s roommate awakened me, “shushing” me to keep me from disturbing the guard. I envisioned a firing squad at midnight and other scenes from the movies. In fact, my guard’s roommate was going on guard duty and he was offering me his bed for the rest of the night.

Meanwhile, my story was also being written in the United States. My first full day as a POW—April 5, 1945—was also the day my mother had arranged to meet Betts in downtown Pittsburgh to pick out an engagement ring. I had won a few dollars in a poker game and sent money home with instructions to formalize the engagement with a ring.

My father, averring that he had had a premonition that they would hear from me that day, had gone home to await the mailman. Lo and behold, when the mail came, it contained a telegram informing my parents I was missing in action. Dad phoned Betts’s mother and then waited at home to give my mother the news all mothers dreaded.

The next day, April 6, my guard, rifle in hand, escorted me by jeep to the nearby railway station. The platform was jammed with travelers; my guard herded me among the hundreds of civilians and, by command, forced people to make room for us. As the train rumbled toward Berlin, he sat in the seat opposite me with his rifle between his knees. At one point he leaned forward and pushed the rifle toward me until I reached out for it. Then he smiled slightly, leaned back against the seat rest, and promptly fell asleep. We finished the trip to Berlin with me holding the rifle. I can only presume he didn’t want me assaulted by civilians.

Detraining in Berlin, I was reminded of Grand Central Station in New York. Loads of people, lots of tracks, much confusion. We walked to our destination, a Luftwaffe hospital, where I was taken to a ward on the top floor to join two English and seven other captured American airmen.

That night, I had my first taste of an air raid from the bottom looking up. The Royal Air Force rained down on Berlin, as they were doing regularly by then. We lay on our beds in the darkness and, like all the rest, I prayed. I knew from experience that the RAF had no chance of seeing the painted red cross on the roof at night, but the hospital survived.

The next day, an eye surgeon gave me an exam. With a mixture of English and French, he explained that when I broke the bones in my nose, the blood flowed into my right eye and was obstructing the optic nerve. The doctor declared there was nothing he could do since the eye was still filled with blood. As a parting remark, perhaps to give me hope, he said, “maybe after the blood dissolves or is absorbed, the optic nerve may respond again.”

Then followed two more nights of RAF bombings. I spent the day in between talking to my ward mates. We blessed the Lord for our survival, cursed ourselves for the predicament we were in, and pondered the big question: “What is going to happen to us next?”

The next afternoon, a young German woman came into the ward and asked for Oberleutnant Gray. She was the doctor’s nurse; he had told her about me and this was her day off. British tourists had often visited her hometown and she had learned English while growing up. She presented me with a batch of cookies she had baked. She had also brought her guitar and spent the next several hours playing and singing songs in English. I have often thought the military personnel were trying to be nice to the prisoners to establish a good record in the event of war tribunals. I cannot, however, find anything but humanitarian reasons for her actions.

I need to digress here to report what was going on stateside. Although there had been no news of my happenstance, things were proceeding as I had requested. The engagement ring Betts had chosen was ready. My dad did the honors: with tears in his eyes, he formally made my proposal of marriage to Betts.

Back in Berlin, an English-speaking intern informed me that I was to be moved to a prisoner-of-war camp. So, the next day, under single guard, I began another journey. A prison truck delivered my guard and me about 30 miles south, to Stalag III-A—my new home for some unknown time. On the way to the camp lazarett—the military hospital—I walked past the barbed-wire enclosures separating several sections of the camp. Many of the prisoners shouted words of encouragement. Some asked how the war was going and where I was from. One American came up to the wire and handed me a pack of cigarettes.

My new home consisted of a wooden barracks housing about 16 prisoners in a room with double bunks and a small table. There were people from many of the Allied forces: Americans, British, Czechs, Serbs, French, and Poles—with those British captured at Dunkirk in 1940 having the longest internment.

The next day, the lazarett doctor examined me. He was a Serb and before his capture had been the personal physician of King Peter II of Yugoslavia. He told me there was nothing he could do for my eye, but unless my nose received some attention I would have sinus trouble the rest of my life. He took one of those mirrored gadgets doctors wear on their foreheads and jury-rigged it to press my nose bones into position so there would be an open passage for breathing. The next step to ensure good airflow was to carve open a good passageway. You’re right: this wasn’t easy. He used a scalpel and, without anesthesia, scraped on the collapsed bone inside my nose.

Believe it or not, just like the TV series Hogan’s Heroes, the camp’s main section had a clandestine radio where prisoners obtained information on Allied activities. Several longtime prisoners in important positions, my Serbian doctor included, also got passes to go into the local town once a week, presumably to locate supplies. From these two sources, we knew the Allied troops were close and that we should await their arrival.

Several days later, we heard gunfire from tanks and machine pistols. The noises sounded nearby but subsided as the day drew to a close. The next morning, April 22, we awoke to find that the German guards—all of them—had disappeared. The gunfire resumed and approached the camp. With a burst of razzle-dazzle, tanks and armored cars came down the road and penetrated the camp through the gates and fences. Our liberators had arrived. The half-tracks hailed from General Motors, but the tanks were Russian and so were the markings. Yessir; we had been rescued by the Russians. The mechanized forces, finding the camp devoid of Germans, continued westward.

That afternoon, a Russian woman soldier came to the lazarett to give us orders. She informed us that the Russians lived off the land and we would be expected to do the same. A truck would be provided and the lazarett patients would be expected to man it and scrounge the countryside for food.

At one point in the next two weeks, a convoy of American ambulances appeared on the road outside of the gate. They were there for several hours and then turned around and left. We later learned that the Russians had refused to let them take us from the hospital and that they would release us only in exchange for an equal or greater number of Russian prisoners. This shed new light on our situation. We feared that we might be taken to Russia or at least held until an exchange could be arranged, so we devised an escape plan.

We learned that the American forces had advanced across the Elbe River and met up with the Russians advancing from the east. They both had agreed to make the Elbe a demarcation line; the Americans then fell back to the Elbe but the Russians never moved up, leaving a “no man’s land” in between. Several days later, our plans were in place: all the ambulatory patients—about 23 of us—crawled under a tarp in the back of our truck and set off as if on a foraging trip. Once out the gate we turned west rather than east, as we were supposed to do. The gate guard fired a few rifle shots as we raced away—to freedom we hoped.

We drove unmolested; the surrounding quiet amazed us. We encountered a gaggle of German soldiers who raised their arms in surrender. We refused to take them prisoner but did collect some souvenirs: I got a German “baby” Mauser. We continued on until we reached the Elbe, about 40 miles from the prison. As we crossed the bridge the first American soldier I saw, amazingly, was Bill Donkin, who had graduated one year behind me at Wilkinsburg High School, east of Pittsburgh. What a small world!

The next four days—May 7-10—were a blur of transit, camps, and delousing showers. During that time, the war had ended—though we didn’t know that through any big announcement, but through a gradual awareness that something had changed.

On we went, traveling this time on a hospital train to Camp Lucky Strike at Saint Valery, France. We were told that we would quickly be on a ship sailing back to the good old USA. I wrote a V-mail to Betts and my family: I’m alive. I’m O.K. For me the war is over, and I’m on the way home to get married.

On May 26, we finally boarded the SS Argentina at Le Havre, France. The first stop was Southampton, England, where we unloaded British Red Cross girls and loaded on more wounded vets—not a popular exchange. We had hardly gotten started when one of the three ships in our convoy had an engine failure. The rules of the convoy are that you must stick together, so we all limped along at half speed.

Thirteen days after we left Le Havre, we pulled into Boston Harbor. The good thing about the long trip was that with the shipboard food, prepared especially for ex-prisoners, I gained about 10 pounds and felt nearly normal. The first thing they told us in Boston was, “The bank of pay phones are free. All charges are being picked up by the government.” After a long wait, I got my turn, and—would you believe—no one was home at my residence. Betts wasn’t home either. Her mother was, however, and she told me they had not received my V-mail letter and still presumed me missing in action. The following day I got through to my parents who, having heard the news from Betts’s mother, were excitedly awaiting my call.

On the train ride home to Pittsburgh the next day, I was filled with trepidation. I didn’t look my best. Dressed in a plain GI uniform, I wasn’t the suave pilot they had last seen. My broken nose had changed my appearance, I had only one good eye, and I walked with a slight limp from my leg injury. Would Betts still want to marry me? How would my partial loss of sight affect what I could do or should do?

I got off the train and trudged down the platform, using a barracks bag to conceal my limp as I saw Mother, Dad, and Betts waiting for me. We joyously hugged and kissed one another and then proceeded to Dad’s car. We drove home in near silence. Perhaps we were each waiting for the other to break the ice.

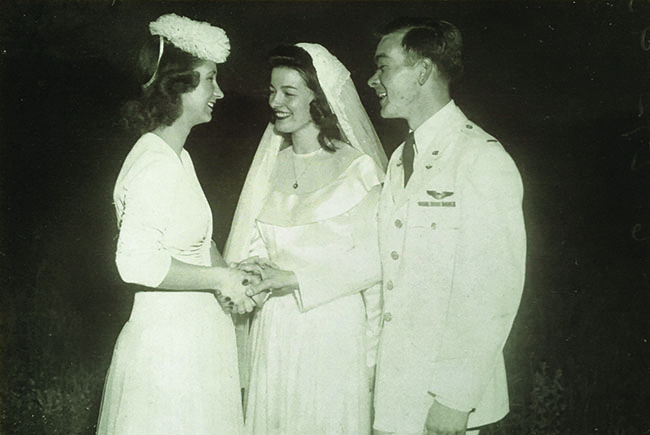

The next several weeks were a whirlwind of visits by aunts, uncles, grandparents, and friends. Planning a wedding became the first order of business. Yes—I told Betts of my eye injury and asked if she still wanted to marry me. With a positive answer, I rounded up a dress uniform from her brother, who would be my best man. The wedding date was set.

On June 27, 1945, at 7:45 in the evening, Lieutenant R. A. Gray married Betty Sue Nunn. And now, decades later, I can truthfully say they lived happily ever after.

I would be remiss, however, if I ended without touching on my reason for writing this at all. Many times I have wished I could go back to thank all those who helped me: the farmer, his wife, and son; the soldier who pushed the bike, and the one who made me a bed; my guard who saw that I was protected on the train; the German doctor in Berlin who examined me, and his nurse who gave up her day off to cheer me up; the Serbian doctor who treated me; the many soldiers of the German and Allied forces who gave me a kind word and genuine concern. Since I can’t find all these people to directly express my gratitude, perhaps this story will provide the remembrance they deserve. ✯