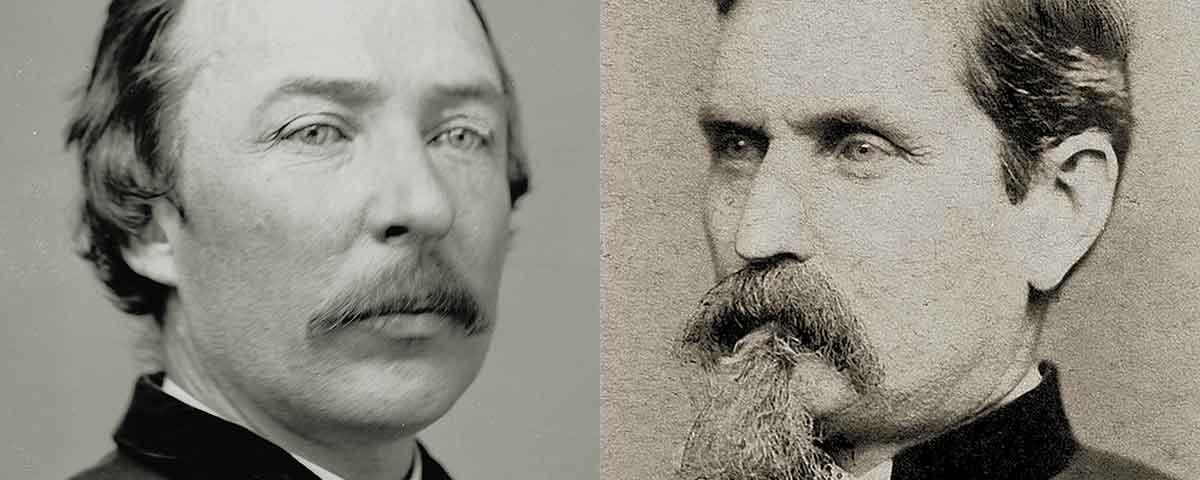

A bitter feud between Generals John Gibbon and Joshua Owen, opposites in every regard, roiled the Army of the Potomac during the war. One would pay a dear price.

John Gibbon’s utter disdain for fellow brigadier general Joshua T. Owen radiated from the pages of his report on the May–June 1864 Overland Campaign. Owen and Gibbon had wrangled once before; Gibbon placed the Philadelphia Brigade’s commander under arrest in the summer of 1863, just before the Battle of Gettysburg. Although Owen was back in command of the brigade by March 1864, the Union defeat at Cold Harbor, Va., in early June spurred Gibbon to attach a damning addendum to his report. Gibbon charged Owen with disobedience and placed him under arrest once more, and soon succeeded in forcing Owen out of the Army of the Potomac altogether.

Was Owen’s poor performance as a brigade commander to blame for his exile, or was it a result of Gibbon’s enmity toward Owen? There are valid points in either debate.

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he Owen family claimed descent from the legendary leader of the 15th-century Welsh revolt, Owain Glyndwr. The youngest of 10 children, Joshua Thomas Owen was born on March 29, 1821, in the village of Bancyfelin, southwest Wales. The Owens relocated to Baltimore in 1835. Joshua’s father, David, opened the publishing company Owen & Co. Joshua attended high school and became an apprentice in his father’s shop.

Joshua Owen enrolled in Pennsylvania’s Jefferson College in 1840. He excelled as a debater and won an award during a contest in 1845. After graduation, he taught school before he was admitted to the bar in 1852. He founded Chestnut Hill Academy with his brother Roger Owen, a Presbyterian minister, in 1851, but it closed five years later. He practiced law, served as a member of the Pennsylvania legislature, and volunteered as a private in one of Philadelphia’s militia units in the years before the war.

The charismatic lawyer enlisted as a private when Confederate batteries fired on Fort Sumter in April 1861. He was elected colonel of the 90-day 24th Pennsylvania Infantry. The regiment saw no action. After it was mustered out, Owen assumed command of the 2nd California Infantry (renamed the 69th Pennsylvania). The regiment took part in the October 1861 debacle at Ball’s Bluff, Va., where its brigade commander, Colonel Edward D. Baker, was infamously killed.

Owen led the 69th with distinction during the 1862 Peninsula Campaign. When Brig. Gen. George A. McCall’s division broke at Glendale on June 30, 2nd Corps commander Brig. Gen. Edwin “Bull” Sumner anxiously galloped up to Brig. Gen. Joseph Hooker, with the 69th close behind, and howled: “General, I cannot spare you a brigade, but I have brought you the Sixty-Ninth Pennsylvania, one of the best regiments in my corps; place them where you wish, for this is your fight, Hooker.”

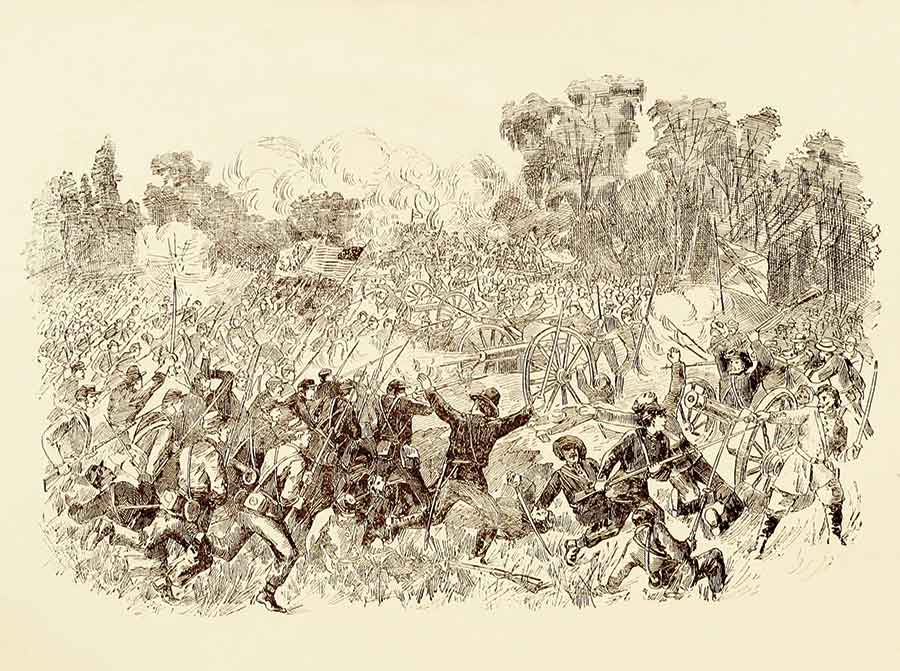

Hooker ordered Colonel Owen to take the 69th and recapture the deserted Union batteries on a nearby hill. The 69th hit the advancing Confederate line with a volley, charged uphill with bayonets fixed, and retook the guns. “I can only express my high appreciation of his [Owen’s] services,” Hooker commended in his battle report, “and my acknowledgments to his chief [Sumner] for having tendered me so gallant a regiment.” Brigadier General John Sedgwick, Owen’s division commander, also expressed his pleasure and declared that “no officer or regiment behaved better,” recommending that Owen be promoted to the rank of brigadier general.

“Paddy” Owen to his men—despite his Welsh lineage—continued to inspire confidence in the fall and winter of 1862. Owen’s fiery speeches, easygoing attitude, and pluckiness in battle commanded respect and confidence from his men. George A. Townsend of the New York Herald dined with Owen on one occasion and found him to be “the most consistent and intelligent soldier in the brigade.” Owen received his star in November 1862. At Fredericksburg, in December, he was in command of the Philadelphia Brigade. He ended the year with a reputation as a solid 2nd Corps brigade commander.

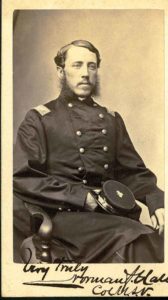

This changed for Owen when Brig. Gen. John Gibbon arrived in the spring of 1863. Gibbon returned to the Army of the Potomac’s 2nd Corps after recovering from a wound he had received at Fredericksburg. Another officer had assumed command of his division, leaving Gibbon in command of Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard’s 2nd Division (Howard was promoted to 11th Corps command). Gibbon’s new command consisted of Brig. Gen. Alfred Sully’s 1st Brigade of five regiments, Owen’s 2nd Brigade (Philadelphia Brigade) of four regiments, and Colonel Norman J. Hall’s 3rd Brigade of six regiments.

Gibbon was the opposite of Owen in nearly every element. He was a professionally trained soldier, cool instead of charismatic, a martinet when it came to discipline, and one who commanded respect through fear rather than friendship. Gibbon would write after the war that “an army commander, to be successful in the field, must be as near a despot as the institutions of his country will permit.” Not the kind of army it seemed that Owen and other volunteers wished to be part of.

Gibbon studied his new brigade commanders. Hall and Sully also were professional soldiers—Hall, a West Pointer who, like Gibbon, had served in the artillery; Sully, the son of famed portrait painter Thomas Sully, had served in the Mexican War and on the California, Minnesota, and Nebraska frontiers. The odd man out was the civilian-turned-soldier Owen. But he wouldn’t be the first chastised by the division’s new commander.

On April 29, 1863, Sully reported to Gibbon that six companies of his brigade’s 34th New York Infantry refused to fight and demanded a discharge because their enlistments were about to expire. Gibbon told Sully to handle the matter. Sully reported back to Gibbon that there was little he could do. Gibbon addressed the mutineers—with the 15th Massachusetts as his enforcers—and threatened to butcher them like hogs if they did not return to their posts. That threat had the desired outcome.

Reportedly enraged by the “inaction and indifference” of Sully, Gibbon issued an order relieving him of command on May 1, two days before his division was to cooperate with Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick’s 6th Corps’ advance on Fredericksburg during the Army of the Potomac’s ill-fated Chancellorsville Campaign. Years later, Gibbon would write in his Personal Recollections of the Civil War: “It was a sad blow to him for he was a good soldier, but the necessity for action was in my opinion, imperative.”

Six days after being placed under arrest, Sully requested a court-martial. The court—composed of Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock, Brig. Gen. Samuel K. Zook, and Colonel Samuel S. Carroll—reported its findings on May 16: “In view of these facts, the court is of the opinion that Brig. Gen. A. Sully, U.S. Volunteers, probably doubted his authority, under existing circumstances, to order extreme measures, and that therefore his action and conduct were not such as to warrant the issue of Brigadier General Gibbon’s Special Orders, No. 122, of May 1, 1863.” Despite the verdict, Sully would spend the rest of the war fighting Indians in the Dakota Territory.

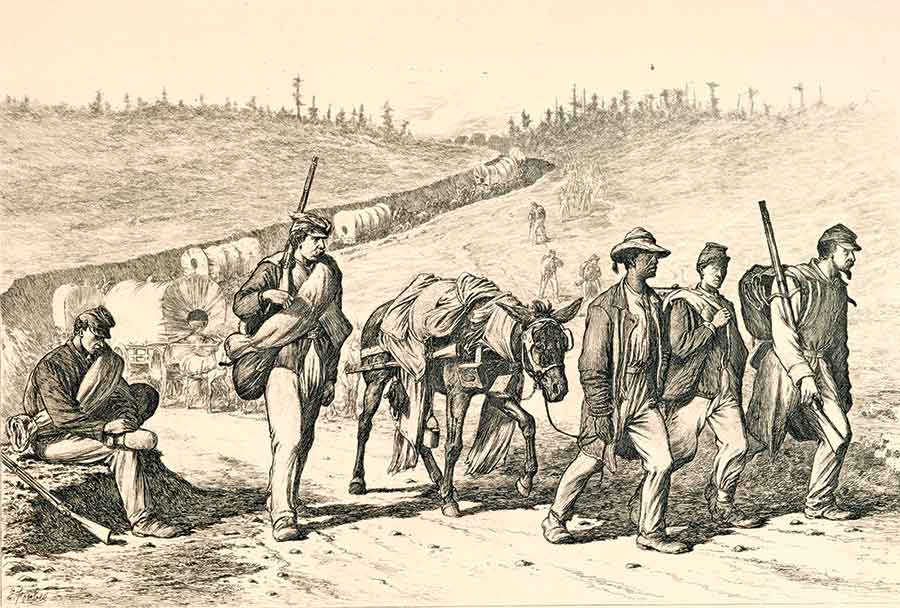

Gibbon’s division moved as part of the Army of the Potomac’s effort to tail Lee’s thrust north in June 1863. On its way to Centreville, Va., the extreme heat led to widespread straggling in the division. Gibbon issued a stern order against the stragglers, asserting that “in the vast majority of cases the straggler is a skulking cowardly wretch who strives to shift his duties upon the shoulders of more honest men and better soldiers.” Gibbon left the division on June 17 to console his wife after receiving word of the death of their 23-month-old son. The division remained on picket duty, and the general returned after two days. On its march back to Centreville from Thoroughfare Gap on June 25, Owen suddenly found himself under arrest by Gibbon.

The actual reason for Owen’s arrest is unclear. No definitive motive for it has been established by historians. One explanation given was that Owen allowed civilians to pass uncontested through his brigade’s picket line. Another attributed it to Owen’s reputation for drinking—he had a physical altercation in October 1862 with then-Lt. Col. Dennis O’Kane of the 69th, supposedly fueled by alcohol. Most experts agree it came suddenly, and unexpectedly, but strangely Gibbon never mentioned it in his Recollections of the Civil War.

The most probable cause is that Gibbon became convinced the Philadelphia Brigade lacked the level of discipline he felt it should have had. Gibbon loathed stragglers, and it appears that Owen’s brigade had the worst offenders. Jonah Franklin Dyer, a surgeon of the 19th Massachusetts, shed some light on Owen’s removal when he noted in his journal on June 28, 1863: “Owen is now under arrest for irregular conduct. He had a very good brigade, but his discipline has been so loose that they have become notorious stragglers….General Gibbon requires everyone on his staff to use his utmost endeavor to prevent straggling.” Whatever the “irregular conduct” Owen committed is uncertain, but Gibbon considered the Philadelphia Brigade the weak link in his division and wanted rid of its commander.

By luck—or by design—Gibbon quickly found Owen’s replacement. The 28-year-old West Point graduate and former member of Maj. Gen. George Meade’s staff, Alexander S. Webb (promoted to brigadier general on June 23), needed a command. Webb was the model brigade commander for Gibbon; he was a polished and professional West Point–trained soldier (like Gibbon, commissioned in the artillery, and the two had served together 1857-59 on the U.S. Military Academy staff and faculty) who had no qualms about shooting stragglers. After taking command, Webb wrote to his wife in disgust that the Philadelphia Brigade was mocked as the “straggling brigade” and that “sixty or seventy [were] absent daily.” When he met his new officers, Webb called them out on how many did not wear rank insignia. Gibbon could not have been happier with the change, and wrote to his wife, “Webb has taken hold of his Brig., with a will, comes down on them with a heavy hand and will no doubt soon make a great improvement.”

Owen’s arrest came six days before the Battle of Gettysburg. The Philadelphia Brigade, under Webb’s leadership, would anchor the Union center during the battle. After the battle, the 2nd Corps commander, Hancock, said: “In every battle and on every important field there is one spot to which every army [officer] would wish to be assigned—the spot upon which centers the fortunes of the field. There was but one such spot at Gettysburg and it fell to the lot of Gen’l Webb.” During the battle, Brig. Gen. Alpheus S. Williams, the 12th Corps’ temporary commander on July 2-3, ran into Owen at the Weikert Farm. Owen, he noted, was “in a sort of roving command” and seemed “not [in] a very clear state of mind.”

Owen assumed command of the 3rd Brigade of Alexander Hays’ 3rd Division in the 2nd Corps in August to replace Colonel George L. Willard, who had been killed at Gettysburg. Major changes came to the organization of the Army of the Potomac in the spring of 1864. On March 26, Owen ‘‘found himself back in command of the Philadelphia Brigade. The men had warmed up to Webb and his stricter approach to discipline while Owen was away. When Webb was assigned to command the nine-regiment 1st Brigade in the same division, Corporal Joseph R.C. Ward of the 106th Pennsylvania Infantry indicated that the departure of Webb “was somewhat lessened by receiving in his stead our old friend, General Owen, who again assumed command of his old Brigade….” John Gibbon also returned to the division, healed from a wound sustained July 3 at Gettysburg.

The fact that Gibbon and Owen would have ended up in the same division despite their differences is unusual. Maybe it was an oversight. Gibbon’s arrest of Owen 10 months before may have seemed inconsequential to retaining the harmony within the division. But unable to rid himself of Owen the first time around, Gibbon made sure he wouldn’t fail a second time.

Near-Miss With Calamity

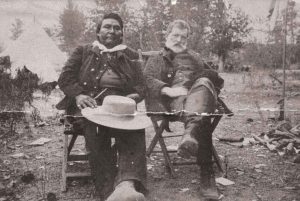

After the Civil War, Gibbon reverted to his Regular Army rank of colonel and served mainly on the Western frontier until 1890, notably in the 1876 Sioux War and the 1877 Nez Perce War. In June 1876, Gibbon led one of the three army columns (Alfred Terry and George Crook led the other two) converging on south-central Montana as part of an effort to force the Lakota “hostiles” onto a reservation in Dakota Territory. Unaware that Crook’s column had been turned back at the June 17 Battle of the Rosebud, Terry’s and Gibbon’s columns pressed on, and on June 25 Lt. Col. George A. Custer’s unsupported 7th Cavalry (of Terry’s column) attacked a large village of Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapahoe Indians encamped along the Little Bighorn River. Gibbon (and the rest of Terry’s column) arrived June 27, in time to rescue the surviving two-thirds of Custer’s regiment under Major Marcus Reno and Captain Frederick Benteen, but they found Custer and nearly 270 7th Cavalrymen dead. Later, at the August 9-10, 1877, Battle of Big Hole against Chief Joseph’s Nez Perce, Gibbon fought a bloody but inconclusive battle in which a third of his command was killed or wounded while the Indians escaped.

Gibbon’s mixed success fighting Indians, however, did not match his noteworthy Civil War achievements. That disappointed Gibbon and likely inspired him to remember his army service in the West as “being shot at from behind a rock by an Indian and having your name spelled wrong in the newspapers.”

Gibbon was promoted to Regular Army brigadier general in 1885, retired in 1891 upon reaching age 64, and died February 6, 1896, in Baltimore, Md. He is among the heroes buried in Arlington National Cemetery. –Jerry D. Morelock

Tensions remained high in the Army of the Potomac in the summer of 1864, especially in Gibbon’s division. Gibbon grieved the one-year anniversary of the death of his young son, John Jr. (“poor little Johnny”). The performance of the 2nd Corps regiments, plagued by high rates of battlefield deaths, exhaustion, and sagging morale, left much to be desired. The excellent working relationship between corps commander Hancock and his division commander Gibbon slowly crumpled to the point of hostility. Beginning with the Battle of the Wilderness on May 5-7 and ending with the slaughter at Cold Harbor in early June, Gibbon left a series of complaints in his official reports against Owen.

At Cold Harbor on June 3, Gibbon’s division failed to break through the Confederate works and suffered terrible losses. Gibbon reported the loss of 65 officers and 1,032 men wounded or killed. “In this bloody assault the division lost many valuable officers and men,” Gibbon wrote, “The loss of such officers as [Henry Boyd] McKeen and [Frank A.] Haskell cannot be overestimated.” The death of Haskell affected Gibbon the most: “I lost two brigade commanders, Gen. Tyler and Col. McKeen and several valuable officers, among them being my poor friend Haskell, who was shot through the head and died a few hours afterwards. I feel his loss very much and was just about to give him command of a brigade.”

Gibbon placed much blame for the failure on Owen. He indicated in his report that he had ordered Owen to be in position on the morning of June 3, ready to rapidly push forward past Brig. Gen. Robert O. Tyler’s and Colonel Thomas A. Smyth’s brigades when they secured a foothold on the enemy’s works. Gibbon complained he instead found Owen’s men asleep and “not even under arms.” After a 15-minute delay, the assault began. “General Owen, instead of pushing forward in column through Smyth’s line, deployed on his left as soon as the latter became fully engaged,” Gibbon wrote, “and thus lost the opportunity of having his brigade well in hand and ready to support the lodgment made by Smyth and [Colonel James P.] McMahon.”

In his 2002 book Cold Harbor: Grant and Lee, May 26—June 3, 1864, Gordon C. Rhea opined that Owen’s move disobeying Gibbon’s order might have been prudent after all. Rhea reasoned that Smyth and McMahon made insignificant progress. The broken and swampy terrain, strong enemy works, and awaiting Confederate reserves spoiled any chance of success. Owen brought his soldiers to the left of Smyth’s brigade, trying to get clear of the swamp, where he thought he could best support a breakthrough. Unfortunately, Owen arrived too late to help.

After what Owen saw as repeated “acts of injustice and oppression” he received from Gibbon, he made the following request to Colonel Francis A. Walker, Hancock’s assistant adjutant general, two days after the battle.

Sir:—I have the honor to request that I may be transferred to some other command, as I cannot consent to serve any longer under the present commander of the division. I do not feel that my reputation is secure whilst serving under him. If I cannot be transferred, then I request that my resignation be accepted, and I be mustered out of the service.

Three days later, on June 8, Gibbon filed charges against Owen, who felt he had angered Gibbon by forwarding his resignation through 2nd Corps headquarters—a breach of discipline. It is possible Gibbon had already made up his mind about placing Owen under arrest. After all, leading up to Cold Harbor he had included defaming comments about Owen in his reports. Cold Harbor proved the final blow.

Gibbon’s order made it up the chain of command, until Meade, under Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s direction, ordered Owen to report to Fort Monroe, where a court of inquiry would try him. But from City Point, Va., on June 27, 1864, Grant expressed in a telegraph to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton that Owen should be mustered out of service instead of facing a court-martial. Grant’s recommendation was wired to President Abraham Lincoln and approved on July 16, 1864. Owen was mustered out two days later. Owen petitioned Lincoln in August asking to face a court—forwarded to Stanton—but nothing came of it.

The soldiers of Gibbon’s division reacted differently to the news of Owen’s exile. John Day Smith of the 19th Maine Infantry disliked Owen as much as Gibbon did. He voiced his own distaste for Owen when he stated that he “was not highly regarded as a commander. His burly form and red face were not seen any more by the Regiment after Cold Harbor. He was placed under arrest and reprimanded by his superior officers so often that it became monotonous.”

Corporal Ward attributed the removal of Owen to the Philadelphia Brigade’s breakup on June 28. “This was a severe blow to our officers and men, one that they keenly felt,” he wrote. “[T]hey did not hesitate at all times to give expression to their feelings whenever General Gibbon was around, under whose order the change was made, which the men attributed to his antagonism to General Owen, whom he succeeded in removing from the command of this Brigade, and now robbed them of their good name and battle-scarred standard, which might have been left to them a few months longer, when their term of service would have expired.”

Gibbon’s enmity toward Owen left the latter’s Army career in shambles. Owen missed out from leading his brigade at Gettysburg, which was more tragic for his legacy than his service getting cut short in 1864. Webb was even immortalized for his role at Gettysburg and received the Medal of Honor for his heroism; Owen would be forgotten, forced to spend the rest of his life desperately trying to vindicate his reputation. He died November 7, 1887.

Frank Jastrzembski, a frequent America’s Civil War contributor, studied history at John Carroll University and Cleveland State University.