New look at sources erodes story about commanders’ infighting contributing to Lee’s escape

The late summer of 1862 was not a good time for Union fortunes in the Eastern Theater.

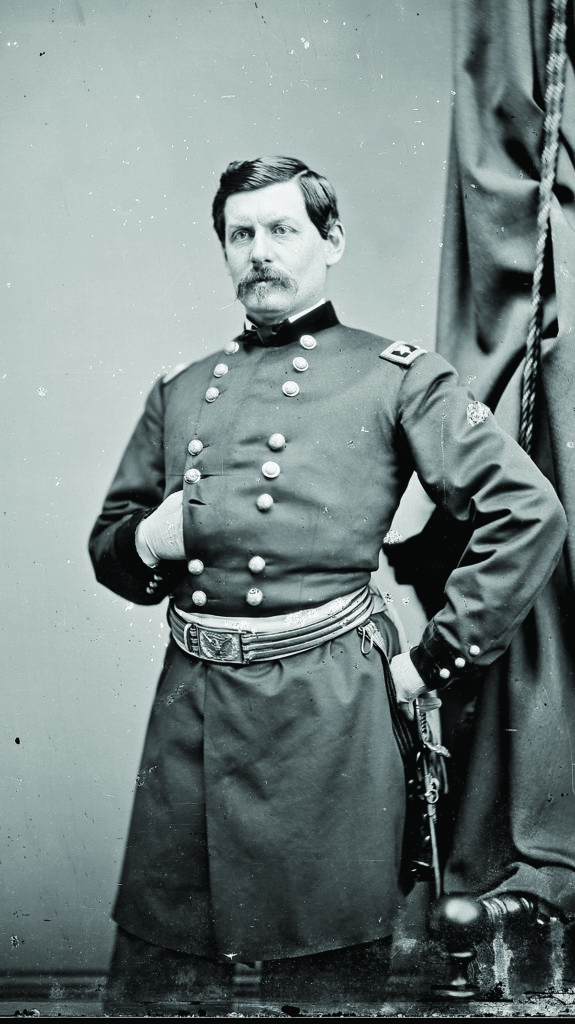

During the August 28-30 Second Battle of Bull Run, Maj. Gen. John Pope’s Army of Virginia went down to defeat at the hands of General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Lee then turned his columns to the northwest, and the Federal high command rushed to merge Pope’s force with Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac to meet the threat.

At the September 17 Battle of Antietam, McClellan won a blood-drenched victory, but Lee managed to escape to fight another day.

Over the years, it has been fashionable for some historians to rely on conspiracy theory to portend why the Federal victory at Antietam was not greater, that discord among the Army of the Potomac’s high command precluded destruction of the Army of Northern Virginia.

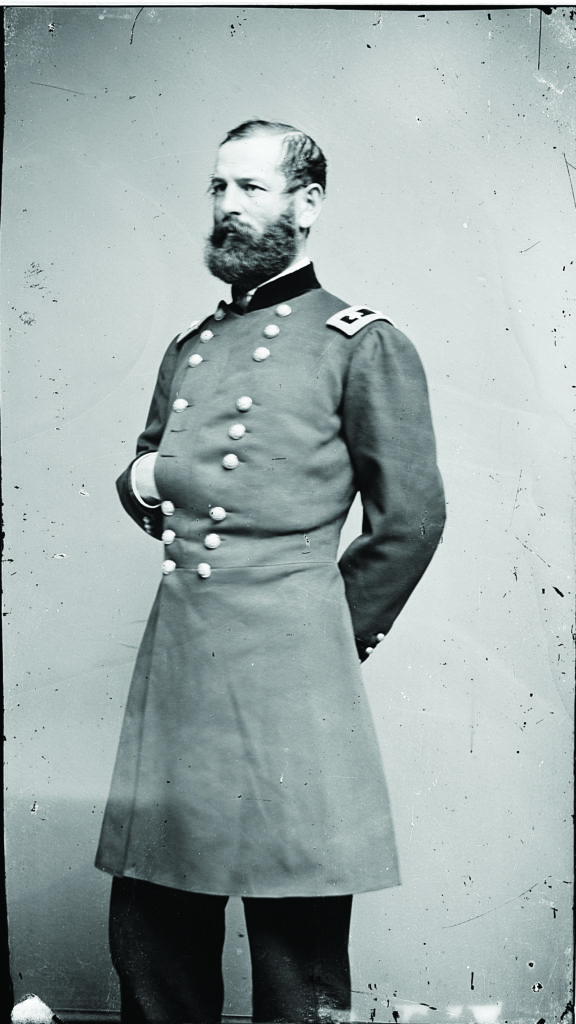

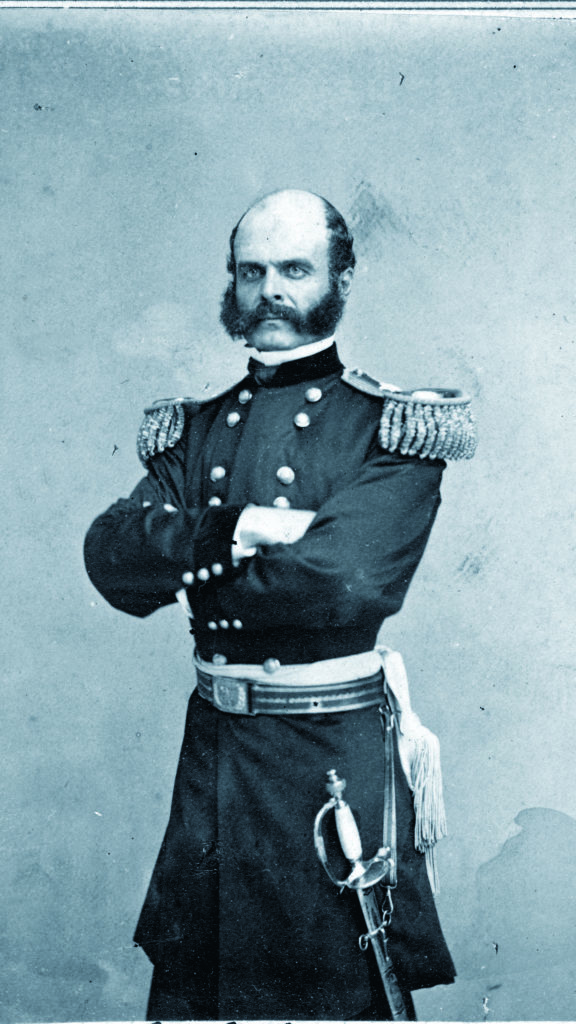

The characters in this supposed ego-over-country drama were all professional soldiers of the U.S. Army. McClellan; Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside, one of his wing commanders; and Maj. Gen. Fitz John Porter, leader of the 5th Corps, knew each other before the war and were considered friends. Each graduated from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point within a three-year period from 1845 to 1847. Pope, an 1842 West Point graduate, also played a role in the drama.

The old story is that the crucible of war caused McClellan and Porter to backbite their formerly affable comrade, Burnside. That infighting weakened the Federal resolve during the critical fighting at Antietam, costing the Army of the Potomac total victory, and hampering the pursuit of Lee’s battered army afterward. A closer look at the sources, however, does not indicate such a controversy existed, and that much of it was a postwar construct.

The generals’ animosity toward each other supposedly originated in Northern Virginia in the summer of 1862. After McClellan’s campaign against Richmond on the Virginia Peninsula came to a close and his army, including Porter’s corps, headed back to Washington, D.C., to join Pope’s Army of Virginia, Burnside also transferred his command from the Carolinas to the Eastern Theater.

As McClellan organized the withdrawal of his command from the Peninsula, Porter and Burnside worked hand in hand during Pope’s campaign against the Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. On August 26, Confederate troops sliced Pope’s communications with Washington. Only Burnside’s telegraph line to the capital city remained open. Lincoln turned to Burnside to keep him apprised of the situation at the front.

Porter passed many of his dispatches along to Burnside during the campaign, especially after the Confederates severed Pope’s communication line. While they included useful military information, Porter also took the opportunity to express to his old friend Burnside his animosity toward Pope and his favoritism of McClellan. “I hope Mac’s at work, and we will soon get ordered out of this,” said Porter in one such dispatch. “It would seem, from proper statement of the enemy, that he was wandering around loose, but I expect they know what they are doing which is more than anyone here or anywhere knows.” With Washington starving for information, Burnside dutifully passed Porter’s messages—slights toward Pope and all—to the War Department.

During the Second Battle of Bull Run, Burnside and McClellan monitored the situation from afar while Porter and his 5th Corps engaged in the fierce fighting. On August 29, Pope’s desired assault by Porter on the Confederate right did not materialize. The next day, Porter’s men attacked straight into the enemy lines, which prompted a Confederate counterattack that ultimately swept Pope’s army back toward Washington.

As Pope’s beaten Federals trudged toward the nation’s capital, trouble began to brew among the Union high command, especially between officers of the Army of Virginia and the Army of the Potomac. The two groups mixed together about as well as oil and water. On August 31, Porter had interactions with the commanders of both armies, writing to McClellan and speaking directly with Pope. In his dispatch to McClellan, he summarized the decisive fighting on Second Bull Run’s final day, August 30, and wrote of the army’s wavering morale, “The men are without heart, but will fight when cornered.”

Porter’s August 31 dispatch, which explained “the true condition” of the Army of Virginia, reached the hands of Lincoln administration officials, however. President Lincoln saw it as early as September 1 and thus, according to McClellan, “had reason to believe that the Army of the Potomac was not cheerfully cooperating with and supporting General Pope.” Lincoln requested that McClellan “as a special favor…use my influence in correcting this state of things.” Specifically, McClellan wired Porter.

On the front lines outside the Washington fortifications, Pope called his corps commanders together on September 2. When Pope arrived, Porter was already present. Porter was confused by the telegram he had received from McClellan the day before and asked Pope for clarification. Pope pulled Porter aside and the two sat in a separate room on a sofa to sort matters out.

Now alone, Pope first related that he had been told by close associates in Washington of Porter’s dispatches to Burnside. Surprisingly, according to Pope’s own questionable account of the meeting, Pope brushed aside these dispatches as “an expression of his [Porter’s] private opinion, in a private letter to another officer.” Pope expressed some displeasure with Porter’s recent performance but believed his conduct at Second Bull Run was “entirely satisfactory.” Pope confided to Porter that he did not plan to “take any action” against the general.

Satisfied with this discussion and Pope’s conciliatory nature, Porter replied to McClellan, “You may rest assured that all your friends…will ever give, as they have given, to General Pope their cordial co-operation and constant support in the execution of all orders and plans.” But the tables turned suddenly on Porter’s career.

John Pope paid a visit to the White House on September 3 and personally spoke with the president. The two were friends, and Lincoln thanked Pope for his performance in the recent campaign and the two spoke freely. At some point, Porter became a topic of conversation. To fuel the discussion, Lincoln showed Pope the earlier dispatches Porter wrote to Burnside, who then subsequently forwarded them to the War Department. As Pope later recalled, these notes “opened my eyes to many matters which I had before been loath to believe, and which I cannot bring myself now to believe.”

After seeing Porter’s dispatches, Pope composed his initial report of the campaign that evening to present to Lincoln the next day. In his report, Pope took Porter to task. “I do not hesitate to say that if the corps of Porter had attacked the enemy in flank on the afternoon of Friday [August 29], as he had my written order to do, we should utterly have crushed Jackson before the forces under Lee could have reached him,” he wrote. “Why he [Porter] did not do so I cannot understand.” Pope sought to publish the report, but Lincoln’s Cabinet voted down such a measure. Lincoln sympathized with Pope, however, and ordered Maj. Gens. Porter, Charles Griffin, and William B. Franklin removed from command so a court of inquiry could examine Pope’s claims against them.

The court of inquiry lasted 10 short days and disbanded “without taking any action.” It was so insignificant that neither Porter, Franklin, nor Griffin knew about it in 1862. In fact, Porter did not learn of its existence until 1879, nor did he hear of Lincoln’s order relieving him from command until 1889.

Though that information never reached Porter in the wake of Second Bull Run, Pope’s battle report did when it was published in The New York Times on September 8. Porter himself first heard rumors of the report on September 10 but, based on their September 2 discussion, could hardly believe Pope’s disparaging remarks. Based on that, Porter requested an examination into the charges, though he wrongly believed Pope was “himself a witness in my favor.” On September 11, Porter managed to find a copy of the New York papers and read the report. It spurred his desire for a quick investigation to clear himself of Pope’s accusations, but the Confederate invasion of Maryland halted his attempts to clear his name.

Although Porter was ignorant of Lincoln’s order removing him from command, as well as the formation of a court of inquiry, McClellan was aware of it. Not pleased, “Little Mac” requested that Porter, Franklin, and Griffin be retained in their commands at least for the extent of the Maryland Campaign. Halleck, Stanton, and Lincoln relented.

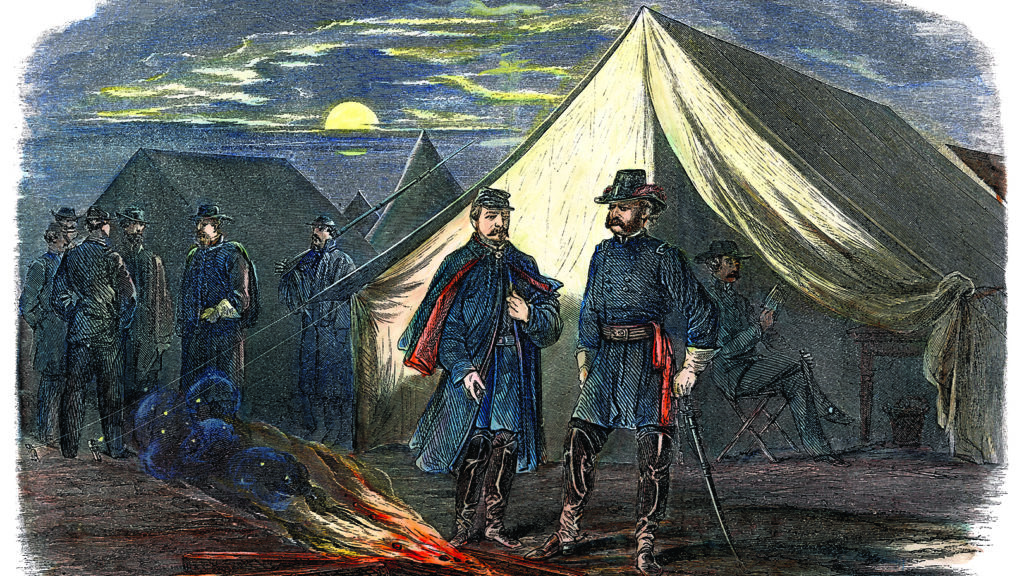

The night after Porter read Pope’s campaign report, Halleck ordered him to take his 5th Corps and rejoin the Army of the Potomac in Maryland. Porter arrived at McClellan’s side on the morning of September 14, with the Battle of South Mountain under way. It was at this moment, as Porter and McClellan stood side by side watching Burnside direct his wing of the army—the 1st and 9th Corps—in its assault against Fox’s and Turner’s Gaps, that the story of a McClellan–Porter conspiracy to undermine Burnside picked up steam. Jacob Cox, a 9th Corps division commander and one of the most fervent proponents of the theory, wrote in 1900 “that the first evidence of any change in McClellan’s friendship toward Burnside occurs within a few hours from Porter’s arrival.” More contemporary evidence, however, tells a different story.

Pope claimed that he informed Porter of the rumors that his dispatches to Burnside had been disseminated throughout the Lincoln administration. That did not, however, fuel any vengeful feelings from Porter against Burnside. Pope’s charges mentioned only Porter’s battlefield conduct, not his letters to Burnside. Additionally, it is important to remember that Porter remained unaware of the Court of Inquiry formed to investigate him. There was no selfish reason for him and McClellan to undermine Burnside.

On the morning of September 15, though, the relationship between McClellan and Burnside changed, and Porter was caught in the middle. Burnside’s wing, under the general’s direction, had achieved success at Fox’s and Turner’s gaps the previous day and had driven the Confederate army from the field. Seeking to pursue Lee’s army quickly, McClellan urged Burnside, “Move promptly.”

To expedite the pursuit, McClellan “temporarily suspended” Burnside’s wing command, freeing the 1st and 9th Corps to operate separately. This is often portrayed as a slight against Burnside, but McClellan likewise divided Edwin Sumner’s wing—the 2nd and 12th Corps—on the night of September 16 when the 12th Corps crossed Antietam Creek to be placed under Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker’s orders. Burnside was present when McClellan ordered the separation and supposedly objected to the order, but he mounted his horse and rode to push the 9th Corps in its pursuit out of Fox’s Gap.

Porter’s corps received orders to follow the 9th Corps through Fox’s Gap, but when the 5th Corps arrived in the gap several hours later, they discovered, much to their surprise, the 9th Corps was still there. McClellan’s order for haste was not obeyed. Instead, “Burnside permitted the troops to view the Battlefield they fought on yesterday,” recorded James Wren of the 48th Pennsylvania in his diary, because “this being a victory for them, he would grant them the privilege.” No record exists that Burnside informed McClellan of the delay. McClellan needed Burnside to move expeditiously to finish off Lee’s army, but Burnside’s delay upset the commanding general’s plans.

Porter, smarting from Pope’s charges, asked army headquarters about what to do since the 9th Corps blocked his path. McClellan ordered Burnside to let Porter pass through. He also asked Burnside to explain his delay.

On his personal copy of the order to move through the 9th Corps, Porter endorsed it with the following note: “Burnside’s corps was not moving three hours after the hour designated for him, the day after South Mountain, and obstructed my movements. I, therefore, asked for this order, and moved by Burnside’s corps.”

McClellan wrote to Burnside the next day demanding “explanations of these failures on your part.” Burnside replied on September 17, the day of the Battle of Antietam. All of this—McClellan’s suspension of Burnside’s wing command, the severe rebukes, and Porter’s asking for orders to push through the 9th Corps on September 15—have led credence to the idea a Porter and McClellan tag team took down Burnside. It is a myth that has been promulgated in multiple histories of the Maryland Campaign.

Without concrete knowledge, however, that his personal correspondence with Burnside had been passed along to the government and without any knowledge of the Court of Inquiry formed to investigate him, it seems strange then that Porter’s supposed maliciousness would have come out of thin air. Instead, the campaign strained McClellan’s and Burnside’s relationship but left Porter’s and Burnside’s friendship intact.

While preparing his campaign report, McClellan told his wife, “I ought to rap Burnside very severely & probably will—yet I hate to do it. He is very slow & is not fit to command more than a regiment. If I rap him as he deserves he will be my mortal enemy hereafter—if I do not praise him as he thinks he deserves & as I know he does not, he will be at least a very lukewarm friend.” In his initial report, McClellan took the middle road. He acknowledged Burnside’s “difficult task” of carrying the Lower Bridge on September 17 but failed to praise Burnside specifically, though it should be noted that McClellan did not single out any of his commanders for specific commendation in the report.

Burnside, in turn, felt ill will toward McClellan. One of his staff officers, Daniel Larned, wrote on October 4, 1862, “I find a bitter feeling against McClellan on the part of all the staff, and the higher power [Burnside] is very quiet.” Eleven days later, a private conversation Larned had with Burnside confirmed “all I have said to you as to the present footing between himself & McC.” But the spat was short-lived. On the eve of the subsequent campaign into Virginia, Larned concluded, “There is no break up of friendship between the two Generals.”

Their friendship faced another extreme test when Burnside replaced McClellan as head of the Army of the Potomac. “Poor Burn feels dreadfully,” McClellan told his wife after receiving the news and speaking with Burnside. “[H]e never showed himself a better man or truer friend than now.” McClellan even wrote to Burnside’s wife informing her of “the cordial feeling existing between Burn & myself.” McClellan’s and Burnside’s relationship did not deteriorate until after McClellan’s second report—more damning to Burnside—was published in 1863. But at the time of the Maryland Campaign, their relationship was stressed but not broken.

Fitz John Porter’s feelings toward Burnside were more affable than McClellan’s in the days of the Maryland Campaign and after. When Porter voiced his anger in the aftermath of the campaign to Manton Marble, editor of the New York World, he vehemently criticized Halleck, Stanton, Lincoln, and Hooker but said nothing of Burnside. Lincoln visited the Army of the Potomac shortly after Porter wrote these words. According to one account, Porter and Lincoln had a private conversation, in which the president said, “I am pleased with your conduct at 2nd Bull Run, and thank you for your telegrams which gave me the only correct information I had of that campaign. You need fear nothing from [the dispatches], for I am grateful to you.”

Until his final days in the Army of the Potomac, Porter held true to Burnside. After Burnside replaced McClellan, Porter wrote: “General Burnside will receive the earnest support of every officer….He is a friend of mine, and if he were not, I should do the same.”

Burnside’s and Porter’s friendship did deteriorate, though not until almost two decades after the Maryland Campaign. In 1880, Porter, after being cashiered from the army in 1863, was fighting for reinstatement. Porter wanted his dismissal reversed and his commission in the Army returned to him. It became a contentious issue in the American political sphere. Burnside, who testified favorably on Porter’s behalf in 1863, found himself embroiled in the discussion again, this time as a U.S. senator from Rhode Island.

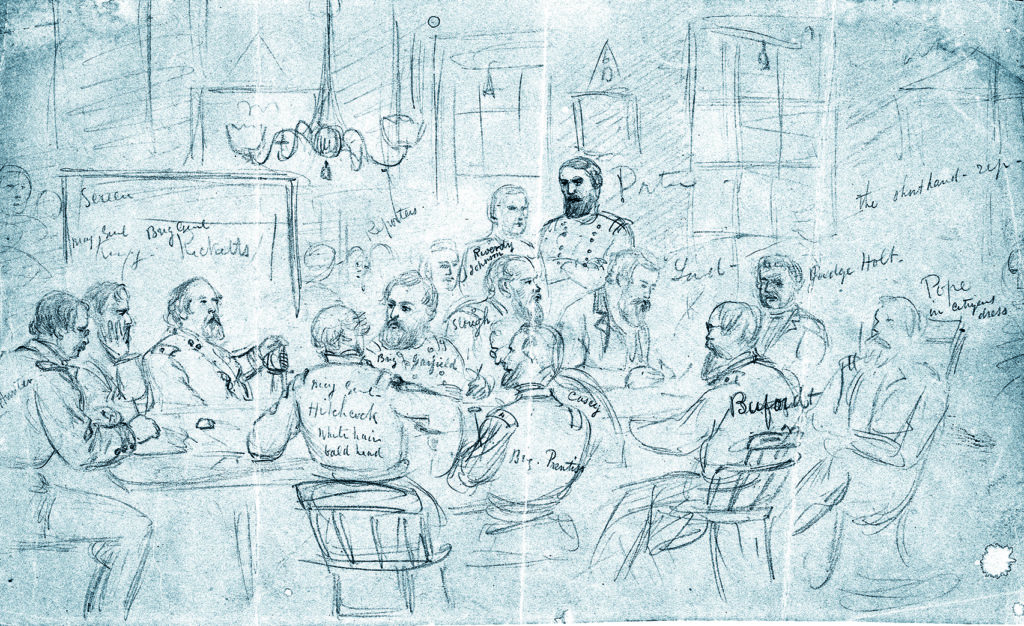

Senator Burnside, formerly a Democrat but now a Republican, differed with Porter about the process. Porter wanted everything reversed and revoked; Burnside believed a new trial should be held. Shortly before giving a speech on the floor of the Senate to state his opinion, Burnside met with President James A. Garfield. Porter’s situation was not new to Garfield. In his younger days, the future president sat on the general court martial board that had convicted Porter. He later said of his assignment, “No public act with which I have been connected was ever more clear to me than the righteousness of the finding of that court.”

It is impossible to say what influence Garfield had over Burnside in 1880. But one thing is clear: Until that night, Porter proclaimed Burnside to be “my professed friend, at times my social comrade.” When it came his time to speak, however, Senator Burnside stood in front of his congressional colleagues and implored them to vote a new trial. The measure failed.

Ultimately, it was within the labyrinth of Washington, D.C., in 1880, where the close relationship of Fitz John Porter and Ambrose Burnside shattered, not on the slopes of South Mountain or along the banks of the Antietam in 1862.

_____

Porter’s Great Trial

The fallout from John Pope’s defeat at the Second Battle of Bull Run fell on several Army of the Potomac generals, all associates of George B. McClellan. Though McClellan shielded Fitz John Porter and the others from censure during the Maryland Campaign, McClellan’s removal from command on November 7, 1862, left Porter vulnerable. Three days later, Porter lost his command and soon fell under arrest to be put on trial.

Pope’s charges against Porter amounted to five counts of disobeying a “lawful command of his superior officer” and three counts of misconduct in the face of the enemy during the August 1862 fight along Bull Run. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton personally approved the nine men presiding over the trial. In this highly politicized case, the stakes for Porter were high. A simple majority of judges was all that was required to convict Porter while a two-thirds majority might inflict the death penalty.

The court opened on December 3, 1862, and lasted until January 6, 1863. On January 21, the court declared Porter guilty of both charges. He lost his rank in the U.S. Army and was barred from ever holding a position in the federal government.

Porter did not sit idly by, and fought the decision for the next 24 years. The case remained politically charged. The 1878 Schofield Board suggested an exoneration of Porter. It was not until 1886, however, that a Democrat-controlled Congress returned Porter to the rank of colonel in the Army. He retired five days later. –K.P.

Kevin Pawlak is a licensed Antietam battlefield guide, the site manager for the Ben Lomond Historic Site in Prince William County, Va., which served as a Confederate hospital after the First Battle of Bull Run, and the author of several books, the most recent of which is Antietam National Battlefield of Arcadia Publishing’s “Images of America” series.

This story appeared in the December 2019 issue of Civil War Times.