‘Saints’ take on the U.S. Army in 1857 struggle for sovereignty

CLICK.”

The unmistakable sound of a rifle being cocked startled the men at the cookfire. Nights on the rolling eastern upslope of the Great Divide had turned cool with fall. The wagoners, employees of the Russel, Majors, and Waddell Freight Company, were famished after a day of hauling U.S. Army provisions bound for the Utah Territory. At the snick of metal on metal the drivers, who had stacked their own rifles nearby, looked over their shoulders to see a young fellow red of hair, face, and bristling beard. Straight-backed and smiling, the intruder held a long-barreled flintlock.

“You boys go ahead and finish your supper,” the redhead said. A driver started to rise. From the darkness, two dozen rifle barrels jutted into view. The driver sat down.

“Now finish up,” said the interloper. “Then we’ll get to work.”

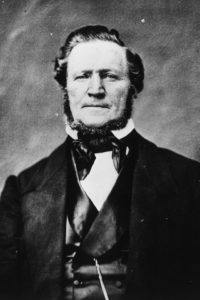

When his prisoners had eaten, the redhead, Major Lot Smith of the Utah Militia, explained that the drivers would be going back to Fort Laramie, 80 miles east. They should gather what they needed from their wagons, he added. The rifles remained leveled. “You won’t have horses,” Smith said, smiling. “So consider what’s worth packing.” Haphazardly outfitted, the prisoners, herded by a few armed riders, shambled into the dark. Smith and the rest of his company stayed. “Heber Kimball is a true prophet,” the commander said, naming a militant Mormon leader. The leader hefted a particularly nice repeater from the stack by the fire. “He said the troops wouldn’t get to Salt Lake City, but goods and cattle would come.” Smith’s men laughed. “He also said,” said one, “that he had wives enough to whip the United States.”

“With our help,” Smith said. “Let’s move out, boys. We’ve got more work tonight.”

That same evening in September 1857, Major Lot Smith’s 24 raiders surprised two more federal wagon trains, burning 74 rigs down to the irons, scattering oxen and cattle, and sending the drivers whence they came. Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston’s U.S. Army force had not even reached Utah Territory and already the federals had lost most of their provisions, including 500 gallons of whiskey.

The Utah War was on.

War can be as much political construct as military exercise, and in July 1857 U.S. President James Buchanan needed political ammunition. The autumn before, the upstart

Republicans, running Californian John C. Frémont and promising to obliterate the “twin relics of barbarism, poly-gamy and slavery,” had nearly beaten Buchanan. Already several southern states were threatening secession and the northern states were doubting the depth of the president’s abolitionist bona fides. Buchanan had relied too heavily on southern support in the election to confront slavery, but he could poke at polygamy, personified by the Mormons—members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which embraced the practice—living far to the west. After years of antagonizing America with their strange beliefs and practices, the sect, forcibly ejected from the States (see “Origins,” p. 43), had emigrated to the unsettled Indian and trapper lands of the Great Basin. Mormon leader Brigham Young was appointed territorial governor after the United States annexed the region in 1850. Young separately declared the independent kingdom of “Deseret,” occupying the high deserts between the Rocky Mountains and the Sierra Nevada and stretching southwest into California to San Bernardino, a Mormon colony. In that desolation, Young organized a thriving theocracy. Mormon bishops acting as probate judges so often sidestepped territorial courts that a federal judge complained to Buchanan that the Mormons were in rebellion—harassing federal officials, ignoring and even subverting federal law, and destroying court records. The aggrieved judge, W.W. Drummond, demanded Buchanan replace Young as territorial governor with a non-Mormon. Secretary of War John Floyd, a Virginian, concurred, for different reasons. Wanting to distract public attention from slavery, Floyd suggested federal troops accompany Buchanan’s new governor to Utah, a move that coincidentally would weaken federal military strength in the East.

Buchanan was playing to his base. Anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant sentiment was gripping the country and national politics revolved around slavery. A muscular response to polygamy might quell secessionist talk in the south and propitiate Buchanan’s northern allies. Buchanan named Alfred Cumming of Georgia territorial governor but inexplicably failed to inform Young, a decision that would prove costly to Buchanan personally and to his party politically.

On July 25, 1857, the 10th anniversary celebration of the Mormons’ arrival in Salt Lake Valley was in full swing east of the city at the head of Big Cottonwood Canyon. Thousands of “Saints” had journeyed 15 miles up the dogleg canyon to escape the valley heat and enjoy Silver Lake’s pine and aspen groves. Bands played, children scampered, and women cooked in preparation for that night’s dinner and dance.

At mid-afternoon, four dusty horsemen rode into camp looking for Brother Brigham. Their leader was Salt Lake City Mayor Abraham Smoot, who, while carrying the June mail east, had seen U.S. Army soldiers mustering at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Learning of the troops’ mission, Smoot had whipped his horse 1,000 miles home to warn his people.

Young was not surprised. A decade ago, on the day they had arrived in the valley, he had told his followers, “If our enemies will give us ten years unmolested, we will ask no odds of them; we will never be driven again.”

After that evening’s festivities, Young asked Daniel Wells, commander of the Mormon militia and his counselor, to alert the assembled Saints to the threat.

Listeners, most of whom recalled tar-featherings, mob attacks, rapes, and murders inflicted on them in Missouri and Illinois, recoiled.

Young asked Wells who might most effectively harry the attackers. “Why, Lot Smith, of course,” Wells said. As a teen Smith had marched with the Mormon Battalion in the American war with Mexico. Now 27, he was a proven fighter, uncommonly brave, noble-hearted, and a faithful Latter-day Saint.

“Send him, then,” Young said. “And send

him now.”

The week before, 2,500 U.S. Army troops had left Fort Leavenworth, accompanied by 400 mule teams, 700 oxen teams, 7,000 head of cattle, and 15 months of provisions. Delayed in Kansas to deal with skirmishes between pro-slavery and free-soiler militants, expedition commander Colonel Albert S. Johnston did not at first accompany his soldiers. Colonel Edmund Alexander, known to the troops as “Old Granny,” stood in for Johnston. Alexander, who ached for a scrap, proclaimed he would “give his plantation for a chance to bombard [Salt Lake City] for 15 minutes.” Anticipating no resistance in Utah, Alexander had sent Captain Stewart van Vliet of the Quartermaster Corps ahead to Salt Lake City to make arrangements for accommodating federal troops.

Returning from Big Cottonwood Canyon, Young, who saw the federals as hostile, declared martial law and called home remote settlers and missionaries. Every able-bodied man was mustered into the militia. Patrols rode east to the plains to escort immigrants heading for Deseret.

During August, federal troops traversed Nebraska along the meandering Platte River, the trail used by pioneers heading for California and Oregon. Young had declared Utah Territory unsafe for non-Mormons, or “gentiles,” and most skirted his domain. But one late-starting party, the Fancher company, knowing that starvation had claimed the Donner expedition a year before, struck south along the Old Spanish Trail. That path passed through Salt Lake City, whose residents viewed the Fancher outfit with suspicion and fear. The Saints, stockpiling provisions against a threatened army siege and fearing the Fancher group might be spies, refused to sell them foodstuffs. The Fanchers responded by raiding gardens and setting their cattle loose in Mormon fields.

Mormons regarded Indians as descendants of a tribe of Israel, and after initial conflict had amicable relations with the Utes, Shoshone, and other natives. Near Fillmore, in central Utah, the Fanchers bartered with a Ute band, reportedly trading them tainted beef that sickened several Indians. The Utes stalked the party, stealing livestock. Some on the wagon train bragged openly of participating in mob actions against Mormons in Missouri. One man brandished a pistol he said had “killed Joe Smith” at Carthage, Illinois, 13 years earlier.

Outraged Mormon settlers sent a horseman to ask Young’s advice. Young said to let the travelers be, but his orders arrived too late. On September 11, at a place called Mountain Meadows near modern day Cedar City, Indians and Mormons set upon the Fancher party, murdering 120 men, women, and children. Word of the massacre stirred fury back East.

In early September, Captain Van Vliet reached Salt Lake City to find the town on a war footing. He told Young the approaching army was merely escorting new federal officials. A doubtful Young invited the officer to a conference that Sunday at which Young’s blistering oratory cataloged

government abuses against the Saints. Heber Kimball, Young’s firebrand counselor, was staring hard at Van Vliet when he said, “But let me tell you, the yoke is off our neck and it is on theirs, and the bow key is in. The day is not far distant when you will see us free as the air we breathe. We will not be governed one whit by the men that are sent here,” to which the congregation of 2,000 shouted assent.

Following the service, a sobered Van Vliet met again with Young, who said if federal troops entered Salt Lake City his people would burn their homes, destroy their crops, and return Utah to desert rather than surrender it. Acknowledging that the Mormons “have been lied about the worst of any people I ever saw,” Van Vliet gave his word that he would do his best to stop the troops bound for Utah.

Van Vliet met Colonel Alexander and the federal army on the western slope of the Great Divide. His reports of Mormon preparations did not impress Alexander. “It is my intention,” he said, “on arriving in Salt Lake City, to capture Brigham Young and the twelve apostles and execute them in a summary fashion.” Unable to discourage Alexander, Van Vliet raced east, hoping to convince President Buchanan to recall the expedition.

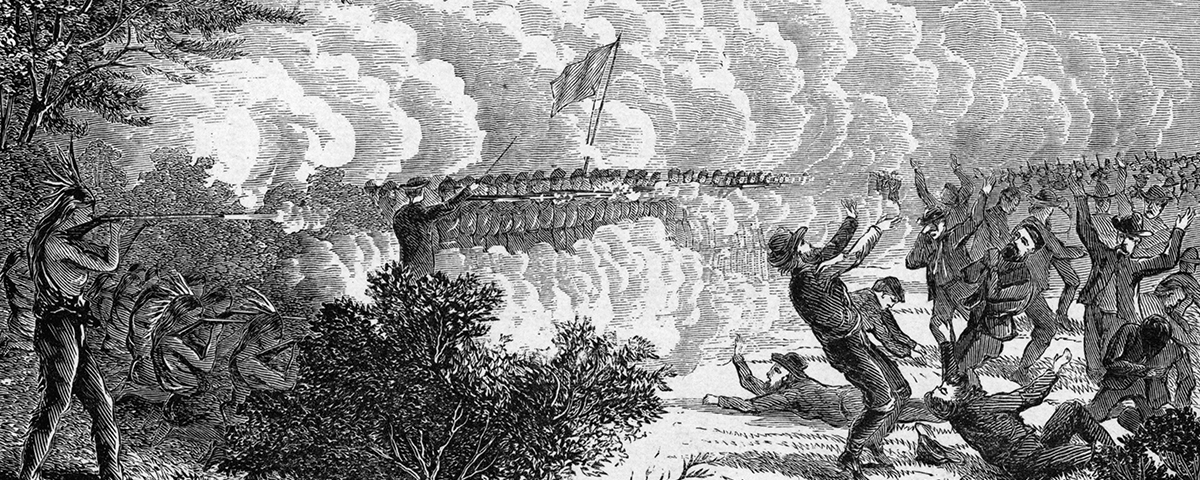

That fall, hundreds of Daniel Wells’s militiamen built stone breastworks along Echo Canyon, a natural bottleneck on the trail 40 miles east of Salt Lake City. Diverting the creek, they forced the road against 200-foot canyon walls and loosened limestone boulders, ready to topple onto the foe. They felled trees across the trail and trenched the canyon floor to obstruct wagons and wheeled cannon.

Lot Smith and his raiders were crisscrossing the Continental Divide, capturing Army supply trains, stampeding cattle, wrecking river crossings, and torching the countryside. At night, they imitated Indians with war cries and movements, keeping the federals on edge.

Jesse Gove, a U.S. Army captain, wrote home in frustration, “If the Mormons will only fight, their days are numbered. We shall sweep them from the face of the earth and Mormonism in Utah shall cease.”

Crossing the Green River in southwestern Wyoming, Alexander, hoping to stop Smith’s persistent raids, mounted 100 soldiers on mules, which the amused Mormon raiders dubbed the “Jackass Cavalry.” In their one encounter, militia and soldiers exchanged rounds, but the only damage was a bullet through a raider’s hat and a horse grazed by a slug.

In mid-October, the Army still had more than 100 miles to go to reach Salt Lake City when a blizzard hit, killing cattle and consigning soldiers to shiver at their fires near Fort Bridger, which Smith and his raiders had reduced to little more than scorched walls. Johnston, accompanied by Territorial Governor Cumming and two federal judges, caught up with his command.

Johnston renamed the ruins “Fort Scott” and ordered his men to make camp. From then until spring, Smith made the federals’ winter a hard one. Young, hearing of their distress, helpfully sent a wagonload of salt. Cumming convened a grand jury of soldiers and in absentia indicted Young and 60 subordinates for treason.

News of the stalled expedition galvanized opinion across the country against President Buchanan for sending an ill-advised army into the field. Eastern papers accused Secretary of War Floyd of profiteering on the expedition. All winter, Buchanan reinforced and supplied Camp Scott. By

spring, Johnston had 5,500 soldiers, teamsters, and suppliers ready to invade Utah at the thaw.

In March 1858, recalling how during the Crimean War in 1854 the Russians had threatened to destroy Sevastopol if Britain and allies attacked the port, Young suggested to the Saints that they torch Salt Lake City if federals entered the valley. A unanimous vote affirmed his counsel.

The Mormons had a friend in U.S. Army Colonel Thomas Kane, an ally during painful times in Missouri and Illinois. At Young’s request, Kane petitioned Buchanan, asking to mediate the conflict. Buchanan, fearing his over-extended, ill-conceived expedition might lose to the Mormons, agreed. Kane sailed to Panama, crossed the isthmus, and sailed to California, traveling overland to Fort Bridger and arriving as talk was arising of putting Salt Lake City to the torch.

Convincing Johnston to stand down, Kane brought Governor Cumming into Utah Territory, escorted by Lot Smith’s raiders. They reached Salt Lake City as the Saints were leaving town. As Young coolly relinquished his governorship, Cumming begged him to stop the 30,000-person exodus from Salt Lake City. Young said his people would rather spend their lives in the mountains than endure further oppression. At the territorial offices in Salt Lake City, Cumming discovered that the Mormons had not destroyed federal records but simply “secured” them against falsification. He found the Saints peculiar but hardly savages. Soon Cumming was as pro-Mormon as Kane.

In June, a presidential peace commission arrived with Buchanan’s offer to pardon the Mormons if they would pledge loyalty to the federal government. Young bristled; the Mormons had never been disloyal. But he was a realist and made the pledge, extracting from Cumming a promise that the Army would not tarry in Salt Lake City. Cumming issued a proclamation declaring, “Peace is restored to our territory.”

In June 1858 a disgusted Johnston, as ordered, marched his men through abandoned Salt Lake City past Utah militiamen with torches at the ready in case of a federal misdeed. As they marched 40 miles south to Camp Floyd, the outpost they had established, the well-provisioned soldiers jeered at returning Saints, who were facing starvation because they had missed spring planting season.

At Camp Floyd, however, the Army bartered for milk, eggs, fish, and wheat from Mormons, infusing the local economy with cash, clothing, utensils, and tea, all scarce in Utah.

In 1860, the Republican Party revived its rhetoric against polygamy and slavery and, capitalizing on Democrat fractiousness, vaulted Abraham Lincoln into the White House. James Buchanan lost control of his party, his one-term presidency considered even then a failure.

In Utah, Alfred Cumming was governor, but Young effectively ruled. Young sent an emissary to Washington, DC, to learn Lincoln’s stance toward the Saints. “When I was a boy on the farm in Illinois, there was a great deal of timber which we had to clear away,” Lincoln told the Mormon. “Occasionally we would come to a log which had fallen down. It was too hard to split, too wet to burn, and too heavy to move, so we plowed around it. You go back and tell Brigham Young that if he will let me alone I will let him alone.”

With the April 1861 start of civil war, the Army left for the east, selling locals $4 million in provisions and facilities for a dime on the dollar. Cumming resigned the governorship and, true to his secessionist stance, returned to Georgia. Fellow Confederate Johnston died at Shiloh in 1862. Captain Van Vliet served in 1861-62 as chief quartermaster of the Army of the Potomac, retiring as brigadier general in 1881. He died in 1901 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Withdrawal of the U.S. Army in 1861 left unguarded a section of the new transcontinental telegraph lines stretching from Fort Kearney, Nebraska, to Salt Lake City. In a telegram, President Lincoln asked Young to “raise and equip one hundred men for ninety days’ service” to protect the lines in Wyoming. There would be no federal pay, arms, horses, or provisions. Within the hour, Young once again was asking his friend Daniel Wells who should lead that force.

“Why, Lot Smith, of course.”

By May 1, Smith and the new Utah Cavalry were marching to Independence Rock, 50 miles southwest of Casper, Wyoming, to join the U.S. Army’s 11th Ohio Cavalry in patrolling the telegraph lines. Young’s orders to the Mormon force read, “Be kind, forbearing, and righteous in all your acts and sayings in public and private… abstain from card playing, dicing, gambling, drinking intoxicating liquors, or swearing… and be kind to your animals.” En route, the ex-raiders repaired bridges and roads they had destroyed and rebuilt mail stations Indians had burned. Lot Smith became the first sheriff of Davis County, Utah. He served in the territorial legislature and oversaw Mormon settlement along the Little Colorado River, where he established dairy, sawmill, and ranching operations. In 1886, defending his property near Tuba City, Arizona, he was killed by renegade Indians.