The town’s Unionist passion was so unshakable, Confederates resorted to calling the key western Virginia town ‘little Massachusetts’

[dropcap] F[/dropcap] or Corporal Charles Lynch and his comrades in the 18th Connecticut Infantry, Martinsburg, W.Va., had the feeling of a second home by the time the regiment reached there July 11, 1864. Over the previous two years, the 18th Connecticut had been in Martinsburg on numerous occasions and under various circumstances. In fact, Lynch wrote in his diary on the 11th that the 18th Connecticut regarded Martinsburg as “our home town.” While familiarity with Martinsburg was partially responsible for that feeling, something else added to their comfort: Martinsburg possessed the most substantial Unionist population of any community in the Shenandoah Valley. While Lynch wrote of visiting Unionist “friends” when in Martinsburg, other Union soldiers who spent time in the community noticed the strong Unionist sentiment, too. More than two years earlier, Sheldon Colton, an officer in the 67th Ohio Infantry, wrote his mother that Martinsburg contained “some pretty good Union men and women…[they] are very kind to us, and help us all they can.”

As Virginia debated secession in late 1860 and early 1861, support for the Union remained strong throughout the Valley. Fifteen of the 19 delegates who represented the Valley’s communities at the secession convention in Richmond were pro-Unionist, including both from Berkeley County—Edmund (sometimes spelled Edmond) Pendleton and Allen Hammond. Both voted against secession on April 4, 1861. Thirteen days later, following the war’s opening salvos at Fort Sumter and Abraham Lincoln’s call for 75,000 volunteers to suppress the rebellion, both Pendleton and Hammond voted against secession, though Hammond later changed his vote and eventually signed the ordinance of secession. Pendleton, who earned the title “Edmond, the Staunch and Steady,” for his support of the Union, never wavered and refused to sign the ordinance.

While Unionist sentiment throughout the Valley waned in the wake of Virginia’s secession, Martinsburg and Berkeley County proved Unionism’s bastion. Of all the Valley’s counties, Berkeley was the only one whose majority of eligible voters opposed the secession ordinance, doing so by a vote of 1,226–428.

In the weeks leading up to the secession referendum vote on May 23, 1861, Unionists in Martinsburg held large gatherings aimed at countering secessionist sentiment. For example, a newspaper correspondent reported that a gathering of Unionists at the courthouse in Martinsburg on May 13 was so large that the crowd poured out of the chamber in which the meeting took place into the main hall and to the building’s front door. News of this activity unnerved Confederate officials in the region. Two days before the statewide referendum, Colonel Thomas J. Jackson sent a dispatch to Robert E. Lee, who commanded all Virginia forces, “that in Berkeley things are growing worse…the threats from Union men are calculated to curb the expression of Southern feeling.”

With support for the Confederacy increasing throughout the Shenandoah Valley during the spring of 1861, the question remains as to why Unionist sentiment in Martinsburg and Berkeley proved so strong and remained so for the conflict’s duration. While various elements contributed to the cultivation of Unionist loyalties throughout the Valley and the broader South—religion, ethnicity, familial connections to the North, and political beliefs—an additional factor contributed to the staunch Unionist sentiment of those from Martinsburg and surrounding environs: the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad.

The B&O came to Martinsburg in 1842 and proved critical to the success of the local economy. “The economic effect of the Baltimore and Ohio railroad was very great….The wealth and welfare of the people were much improved and they realized a new era had begun,” one chronicler noted. Throughout the conflict Confederates who passed through Martinsburg believed the railroad the most significant factor that made “most of the people” into “bitter Unionists.”

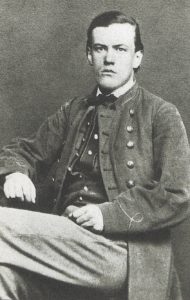

Confederate artillerist John Hampden Chamberlayne believed that the B&O “ruined” Martinsburg and Berkeley County. William S. White, 3rd Richmond Howitzers, concurred. On September 18, 1862, White penned in his diary that Martinsburg “is very different in character” from other locales in the Shenandoah Valley because it was “situated on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.”

Unionist sentiment in and around Martinsburg not only proved anomalous due to the number of Unionists there, but also because of how aggressively they supported the Union war effort. While Unionists throughout the Valley did things to undermine the Confederate war effort—such as those in Rockingham County, who spirited men of military age out of the Valley via a Unionist Underground Railroad to avoid conscription into Confederate service—they usually did so as clandestinely as possible for reasons of self-preservation. In Martinsburg, however, that did not seem to be the case.

Less than one month after Virginia’s secession referendum, a contingent of cavalry commanded by Colonel J.E.B. Stuart arrived in Martinsburg to burn the colonnade bridge that carried the B&O over Burke Street. The bridge—a gift to the citizens of Martinsburg from the B&O “as an especial compliment to the city”—was constructed in the early 1840s. About 8 p.m. on June 13, Stuart’s men destroyed the bridge, one of the town’s architectural landmarks. Martinsburg resident John Curtis wrote that the bridge’s destruction “incensed [the] Union men very much.”

In addition to giving Southern soldiers “an unexpected lick or knock-down” in the days that followed, railroad workers and their families expressed their disapproval in a more verbose fashion. As a Confederate company, men Curtis believed hailed from Clarke County, Va., drilled in the square in front of the courthouse, the crowd shouted at the soldiers and threw stones. After a stone struck one of the Rebels, they, according to Curtis, “brought their guns to shoulder, ready to shoot.”

Perhaps somewhat unbelievably Curtis wrote that at this point the “crowd made a break toward” the soldiers. Not wanting the situation to escalate, the troops retreated into Grantham Hall, a meeting place at the southwest corner of King and Queen Streets. The angry Unionists remained outside the hall “for some time” and “hooted and howled.”

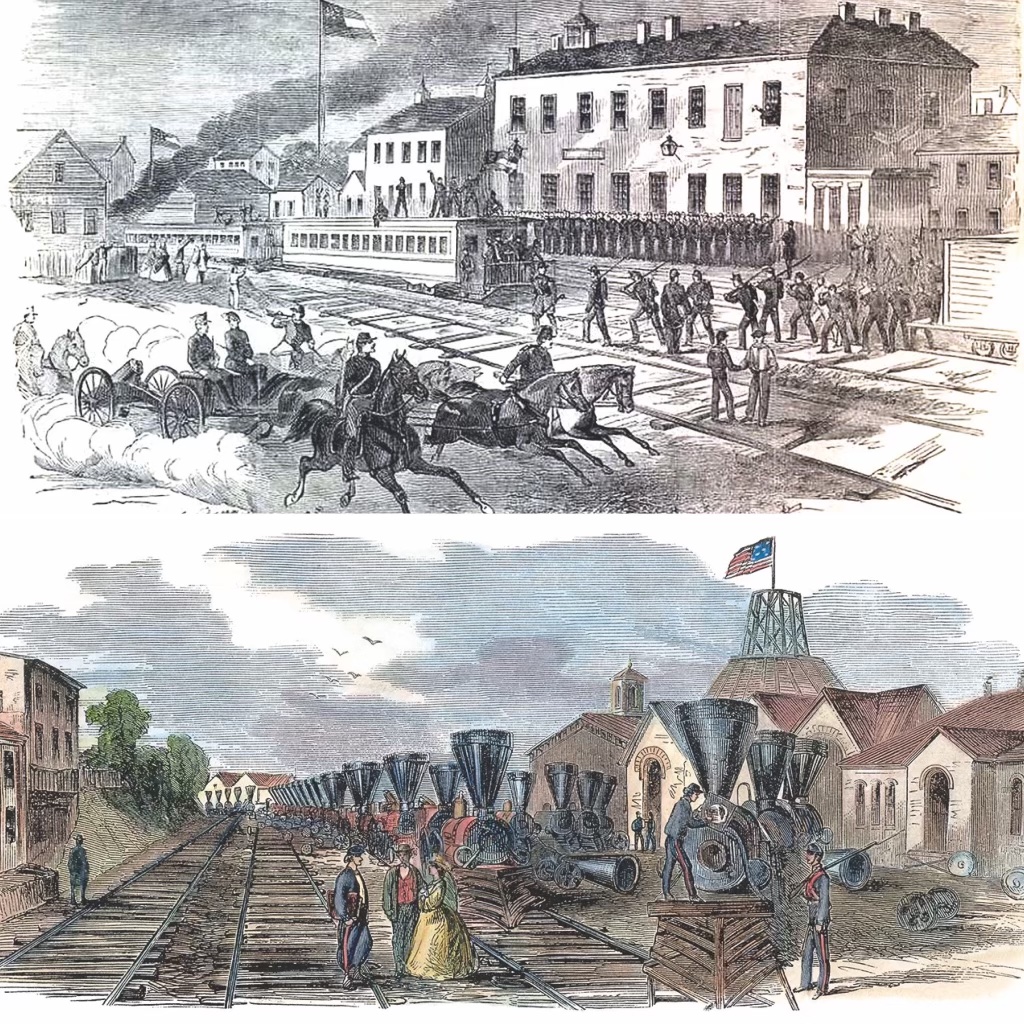

The ire of Martinsburg Unionists only increased days later when General Joseph E. Johnston, the overall Confederate commander in the Valley, ordered Jackson to proceed to Martinsburg and destroy the B&O Railroad shops to prevent their use by Union troops. Although Jackson disapproved of the order, as he thought the equipment in Martinsburg should be confiscated and used for the Confederacy’s benefit, he carried out the order on June 20. As Jackson’s troops engaged in the work of what one of his men believed “look[ed] like vandalism”—tearing up track, burning the roundhouse and various shops, and destroying 56 locomotives and 305 coal cars—the community’s Unionists looked on in disbelief. Reportedly, one female Unionist, so incensed by what Jackson’s men had done, verbally chastised a contingent of Confederates and told them she hoped Union General Winfield Scott would capture them and execute every Confederate involved in the destruction.

While surviving accounts suggest that the Unionists who displayed outrage against Confederates in the war’s opening months were both male and female, evidence suggests that it did not take long for Martinsburg’s male Unionists to assume a more cautious posture when Confederate troops were near. For example, during Union Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks’ retreat north following his defeat at the First Battle of Winchester on May 25, 1862, a number of Martinsburg’s male Unionists joined Banks’ column as it marched toward Williamsport, Md. David Hunter Strother, a Martinsburg native who served on Banks’ staff, recorded that a “number” of “loyal…male citizens…joined our train of refugees” for Maryland. The move wasn’t permanent, however. Once Union forces regained control of the area around Martinsburg by the first week of June, the Unionist refugees returned. As Colonel Strother rode south toward Martinsburg on June 3, 1862, “to visit some friends in Martinsburg,” he noted that the “road was alive” with returning refugees.

Although the decision to flee to Maryland might be viewed as being done out of an overabundance of caution or perhaps even seem cowardly, evidence indicates the decision for White men, especially those of military age, to leave proved wise. Since the war’s outset, Confederate troops who entered Martinsburg adopted various measures to suppress White males who in some way undermined the Confederate war effort. For example, in June 1861, about the time Confederates destroyed the colonnade bridge, troopers from the 1st Virginia Cavalry arrested 25-year-old George Zepp “for advocating the Union cause” and refusing to “join their army.”

Zepp’s detainment did not last long. Unclear whether he escaped or was released by his captors, Zepp offered his services to Union Maj. Gen. Robert Patterson after his command entered Martinsburg the first week of July. Despite his arrest and threats of being hanged should he continue to undermine the Confederacy’s cause, Zepp not only offered his service to Patterson, but also to other Union officers during the war, including Generals Banks and Philip Sheridan as a “scout and detective.”

John Dalwick, 46 years old at the war’s outset, described by Martinsburg Unionist Ferdinand Gerling “as good a Union man as there was in Berkeley County,” supported the Union war effort in various ways. When Patterson’s Union army occupied Martinsburg in July 1861, Dalwick “collected money to make a Union flag.” On July 12, Dalwick, along with Mary Miller, presented a flag made of wool to the 11th Pennsylvania Infantry. The 11th’s chaplain, William Henry Locke, noted that it was “a beautiful national flag” presented to the regiment “in acknowledgment of our first victory over the rebels at Falling Waters.”

Dalwick’s commitment to the Union war effort extended beyond his activities in the summer of 1861. Throughout the war Dalwick loaned Union soldiers money and he, along with his wife Catherine, nursed wounded and sick Union soldiers at various points during the conflict. Perhaps most significantly Dalwick secreted Union soldiers separated from their commands during various retreats through Martinsburg and then guided them to Union lines.

While male Unionists such as Dalwick and Zepp supported the Union war effort in civilian, non-combatant capacities, others enlisted in the Union Army. Nearly 200 men from Martinsburg and Berkeley County enlisted in one of two companies organized: 133 enlisted in Company C, 3rd West Virginia Cavalry, while another 66 enlisted in Company B, 1st Virginia (U.S.) Infantry. There is evidence that others Unionists from Martinsburg and its vicinity ventured into Maryland and enlisted in the 1st Maryland Infantry (U.S.) or enlisted in companies organized in Williamsport by Ward Hill Lamon, a Winchester native who worked in various capacities in the Lincoln administration.

Although there are not precise numbers for the total who enlisted in units beyond the two from Berkeley County, juxtaposing those estimated enlistment figures against the number of men from the county to serve in one of the five Confederate companies provides perspective on the strength of Unionist sentiment in the area: 381 individuals from Martinsburg and Berkeley County served the Confederate war effort, meaning that, at a minimum, approximately 35 percent of those serving in Martinsburg/Berkeley County military units during the conflict did so in Union blue.

As Martinsburg’s male Unionists supported the Union war effort in some manner, so too did the women whose sympathies leaned North. Throughout the conflict, these women offered care and comfort to wounded Union soldiers or those separated from their commands. Among those in the community who lent such critical support were Amanda and Ann Hafner, seamstresses in their late 20s who, according to artist-correspondent James E. Taylor, cared “for sick and wounded Federals” and supplied “refreshments and coffee to hungry and thirsty stragglers seeking their commands.”

Irish immigrant Bridget Delaney, 51 years old at the start of the war, contributed admirably as well. After Taylor interviewed Delaney in 1864, he recorded that she “had done more for the Boys in Blue than anyone in Martinsburg.” Throughout the conflict, Union soldiers such as Captain George A. Sexton, 3rd West Virginia Cavalry, also testified to Delaney’s tireless effort to support the Union. Sexton, recalling a conversation he had with Taylor in 1864, stated that Delaney “the good soul is always on the go and never seems to have a moment to spare for rest.”

Delaney, despite the praise heaped upon her by Taylor, Sexton, and others, did not believe she deserved any of it and insisted there were considerably more women in Martinsburg who did more. “There are plenty of my sex here who do much more for the boys, God bless them, that I do,” Delaney informed Taylor somewhat “deprecatingly.” Nevertheless, Union soldiers cared for by Delaney appreciated her help so much that they ventured back to Martinsburg in the decades after the conflict to visit and pay their respects.

Among those who visited Delaney after the war was Sergeant George W. Toms, 5th New York Cavalry. After traveling to Martinsburg in 1891, Toms wrote an article for the National Tribune that not only praised Delaney as someone “who did so much for the Union,” but also urged comrades who now enjoyed financial “prosperity” to be charitable to Delaney, now 81 years old “and unable to do anything.” Delaney died two years later.

While the work of the Hafner sisters and Delaney was typical of the ways women supported the Union war effort, that devotion manifested itself in other ways. Sometimes commitment to the Union prompted open defiance against Confederate troops. For instance, following Rebel victory at the Battle of Martinsburg on June 14, 1863, portions of Confederate Maj. Gen. Robert Rodes’ Division met with stiff resistance from the community’s female Unionists after Rodes’ men entered town in the wake of a retreat by Brig. Gen. Daniel Tyler’s Federal forces.

A female Unionist, identified by one North Carolinian as “a Dutch woman of strong Union brawn,” accosted Captain John Gorman, 2nd North Carolina, with “a paddling stick.” Unable to shake the woman, Lieutenant Frank Harney of the 14th North Carolina intervened and informed the woman that if she did not cease immediately “he would pull every hair out of her head.”

Several weeks later during the Confederate retreat following defeat at the Battle of Gettysburg, Martinsburg’s Unionists offered food and water to Union prisoners of war being escorted south. While Unionists, male and female as well as young and old, offered foodstuffs, Union prisoners made particular note of the courage Martinsburg’s female Unionists showed. Captain R.K. Beecham of the 2nd Wisconsin Infantry, captured on the first day of fighting at Gettysburg, wrote that the “ladies especially were persistent.” As Unionists threw “loaves of homemade bread, biscuits, crackers, [and] cakes of all kinds” into the lines of Union prisoners, Confederate guards took measures to stop it. Beecham recalled one episode when an unidentified Rebel officer threatened a group of women with his sword, noting that the threat had little impact. With “cheeks glowing with the fire of indignation,” Beecham recalled that one unidentifiable woman approached the officer and “in contempt of his authority…with the fire of indignation and her eyes flashing defiance” told the Confederate, “‘Oh, you needn’t think you can scare us.’”

Slightly more than one year later, during the first week of July 1864, when Confederate troops commanded by Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge entered Martinsburg to carry out an order by Lt. Gen. Jubal Early to “seize all other goods in the stores” in the community and burn all the bridges in the area, Mary Miller seized the opportunity to show her disdain. As Breckinridge’s troops passed in front of Miller’s home on Union Hill, a place named so by Martinsburg’s Confederate sympathizers due to the large number of Unionists who lived in that area, she snatched the Stars and Stripes that she had presented the 11th Pennsylvania in 1861, wrapped it around herself, stood in the middle of the street and reportedly chastised Breckinridge’s troops as “shame-faced traitors in fighting against the flag of their country.” Weeks after the episode James Taylor spoke with Miller noted that “unintimidated by [the Rebels’] threat of bullet and bayonet….Miller was terribly in earnest…an example of reckless courage and grit.”

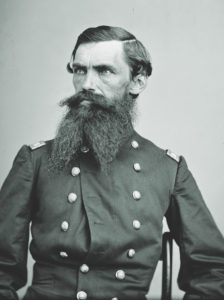

Perhaps one of the most daring acts the community’s female Unionists performed came on October 1, 1862, when 700 Union cavalry commanded by Brig. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton made a reconnaissance to Martinsburg. At the time, Confederate Brig. Gen. Wade Hampton’s cavalry brigade was positioned “in the center of the town.” Pleasonton arrived on the town’s outskirts about 2 p.m. and drove away Hampton. None of what he achieved, however, would have been possible if the female Unionists had not hastily repaired a bridge over Tuscarora Creek that had been made impassable by Hampton’s troops. According to David Hunter Strother, as soon as these women spied “the Union banners…advancing over the hill” they rushed from their “houses and replaced the flooring of the bridge” so that Pleasonton’s “column was enabled to pass over it without a halt.”

This act proved a nice surprise to Pleasonton who acknowledged he was aware Hampton’s troopers had destroyed “two bridges between my forces and theirs.” When Pleasonton learned that “the ladies of the place had turned out and built them up for my men to cross,” he remarked it was a telling example of the “exhibition of the loyalty and devotion in the present great struggle for national existence.”

The varied acts of support for the Union war effort among area Unionists created a sense of dread for many Confederates whenever they approached Martinsburg. Although Martinsburg and Berkeley County had Southern sympathizers, the number and boldness of Unionists was without parallel in the Shenandoah Valley. In June 1861, Alexander Tedford Barclay of the 4th Virginia Infantry called the town “the meanest Abolition hole on the face of the earth.” More than one year later, Confederate artillerist William White referred to Martinsburg as a “detestable place.”

Some Confederates feared area Unionists so much that officers prohibited troops from drinking out of wells, as one soldier explained, “for fear the wells are poisoned.” Some Confederates believed Unionist sentiment so strong that they branded Martinsburg “Little Massachusetts”—a nomme de guerre the locals proudly accepted, as one Unionist made note, as a “compliment to their spirit, their patriotism, and their civilization.”

Although it is difficult to fully quantify the impact Martinsburg’s Unionists had on the Civil War’s course in the Shenandoah Valley, their myriad efforts—military service, scouting, secreting Federal soldiers separated from their commands, caring for wounded troops, and providing foodstuffs and supplies—proved critical to Union success. Although in the decades following the Civil War, various Union soldiers reflected fondly about Martinsburg’s Unionist sympathizers in regimental histories, reminiscences, and articles in the National Tribune, perhaps it was Orwin H. Balch of the 147th New York—who had passed through Martinsburg in July 1863 as a prisoner of war—who best explained the strength of that sentiment. After watching Confederate soldiers threaten and arrest a male Unionist for “feeding starving” Union soldiers, Balch believed this individual the epitome of “a true and brave man” in a place unlike any other community he had experienced south of the Potomac River. Decades after the war, Balch wrote of the uniqueness of Martinsburg’s Unionists, stating simply, “I must say that the strongest sentiment was manifested in this place that I been through during the time that I have been in service.”

Jonathan A. Noyalas is director of Shenandoah University’s McCormick Civil War Institute and the author or editor of 13 books on various aspects of Civil War–era Shenandoah Valley history.