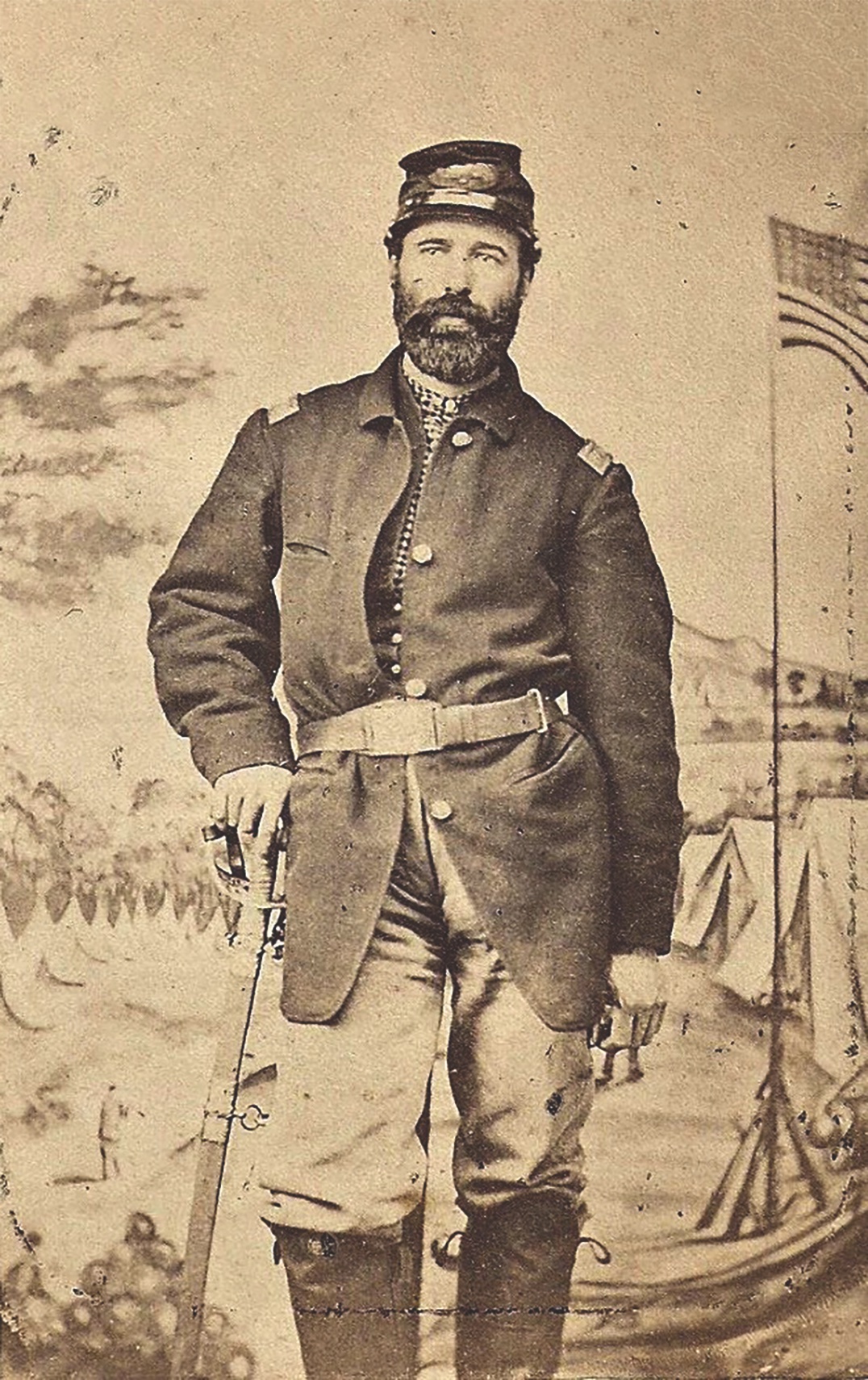

As the soldiers of the rookie 118th Pennsylvania Infantry waited on the Virginia bank of the Potomac River for orders the morning of September 20, 1862, Captain Francis P. Donaldson spotted Lieutenant Lemuel L. Crocker nearby. The two were from different companies, but Donaldson, a veteran with previous service in the 71st Pennsylvania, had taken a liking to the friendly, powerfully built Crocker, a New Yorker from the Empire State capital of Albany. In 1851, Crocker had moved to Philadelphia, where he worked as a merchant before accepting a commission as a lieutenant in the 118th—known as the “Corn Exchange Regiment.” On September 20, he had served for a mere 34 days.

The position they occupied that morning reminded Donaldson of Ball’s Bluff, Va., with its steep bluffs lining the river, site of a fierce battle in October 1861. Now, three days after the Battle of Antietam, the 118th was part of a reconnaissance in force by the 5th Corps across the Potomac in the direction of Shepherdstown, Va., and points south, to determine the direction the Confederate army had taken after its retreat from Sharpsburg.

Soon, the unit was ordered to join other regiments of its brigade up on the bluffs. By the time they reached the summit, however, the Federals were under attack by the Confederate division of Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill. To its horror, the 118th learned early in the engagement that many of its Enfield 1853 pattern rifles were defective. In some cases, the hammer spring of those weapons was not strong enough for the hammer to break the percussion cap; in others, the nipple, where the percussion cap was placed, would break off when struck by the hammer. Both defects rendered those weapons useless.

Company officers such as Donaldson and Crocker frantically searched along the lines of their companies for functioning weapons that other soldiers had dropped. When Donaldson and Crocker encountered one another, Crocker exclaimed, “God! Captain, was Ball’s Bluff like this?” to which Donaldson replied, “Crocker, we are beaten and you had better look to the rear for a safe retreat for the men.”

Bedlam soon engulfed the regiment, which finally “broke in wild confusion for the river.” Hill’s men swarmed along the bluffs and into an abandoned cement mill near the riverbank, and proceeded to pick off the panicked Pennsylvanians as they attempted to ford the river to safety back in Maryland. Two days later, in a letter to his parents, Crocker recalled, “We retreated amidst such a shower of lead I never want to take the risk again of coming out of.” He admitted, “I was cool and collected during my travel by the river-side,” but that when he reached the mill dam, which many were using to cross the river to safety, “I think my cheek blanched, for it seemed to me certain death to cross it.”

Donaldson, who had been nearby, wrote how much of the regiment, “beaten, dismayed, wild with fright, all order and discipline gone, were rushing headlong towards the dam.”

What may have saved Crocker’s life and enabled him to cross safely was the arrival of the 1st U.S. Sharpshooters, who lined the drained bank of the nearby C&O Canal and cleared the bluffs of Confederates. After the fighting subsided some 20 men of the regiment, both wounded and those “whose courage had given out,” remained on the Virginia bank, too terrified to attempt the passage over the river. Crocker and Captain John B. Isler, commanding the Sharpshooters, boldly walked up and down the riverbank in an effort to induce those soldiers to cross but realized they were too terror-stricken to move. Crocker quickly stripped off his uniform jacket and, covered by the rifles of the Sharpshooters and survivors of his regiment, forded the Potomac, getting each one of the men across safely.

Crocker was furious at the ineptitude that had led to the slaughter in his regiment. Whoever ordered the reconnaissance “ought to be court-martialed,” he wrote his parents. Unknown to Crocker, the carnage had resulted largely because his colonel, Charles M. Prevost, a brave but inexperienced officer, had refused to recognize an order to retreat because it had not come through proper channels.

Upset to see his regiment’s dead lying strewn along the line of retreat, Crocker the next morning asked his brigade commander, Colonel James Barnes, whether Barnes could request 5th Corps commander Maj. Gen. Fitz John Porter to send a flag of truce across the river so the wounded could be retrieved and the dead buried. Barnes’ inquiry received “a flat, emphatic refusal.” There would be no flag of truce.

Crocker, however, couldn’t abide the decision, and “in positive disregard of instructions” he forded the Potomac alone, dressed in his full officer’s uniform and carrying his sword and pistol. Watching incredulously, Donaldson declared Crocker’s bravery “beyond my comprehension.”

Crocker climbed the bluffs and carried the bodies of two captains and a lieutenant down to the river. By the time he carried their bodies to the river, he was “absolutely covered with blood and dirt.” Word of what he was doing had made its way to 5th Corps headquarters and Porter dispatched an aide to call for an immediate end to Crocker’s mission of mercy. Spotting the lieutenant on the riverbank, the aide shouted across that if Crocker did not return to the Maryland bank at once, they would shell him out with a battery. Crocker was not easily intimidated. He shouted back, “Shell and be damned,” and went on with his work.

Upon returning to the bluffs, he was confronted by a Confederate general, possibly Fitz Lee, and his staff. They demanded to know what he was doing and on whose authority he had crossed into Confederate lines. Crocker explained himself and added, “humanity and decency demanded that they [the dead & wounded] be properly cared for.” Since no one else was attempting to do this, “he had determined to risk the consequences and discharge the duty himself.”

The general asked Crocker how long he had been in the service. “Twenty days” was the reply. He told Crocker to continue his work and pointed out a boat near the Virginia shore that could be used to transport the bodies across, even deploying cavalry pickets to protect Crocker from other Confederate troops who might not know his mission.

After crossing the river with the bodies of the officers and a wounded private from his company, Crocker was hauled before General Porter. The commander reprimanded the lieutenant, acquainting him with the military laws that established flags of truce and how he had violated those laws.

But a reprimand was his only punishment. As the historian of the 118th observed, “there was something about the whole affair so honest, so earnest, and so true, that there was a disposition to temporize with the stern demands of discipline.” Porter likely also recognized the same thing in Crocker that his friend Donaldson had; “The daring of this man Crocker is beyond all precedent.” The army needed every Crocker it had.

Scott Hartwig writes from the crossroads of Gettysburg. He thanks Jeffery Stocker, who shared Lemuel Crocker’s letter to his parents, originally published in the October 2, 1862, issue of the Buffalo (N.Y.) Advocate.

This article originally appeared in America’s Civil War magazine.