Two 12-pounder Napoleons stand west of the Old Hagerstown Pike at Antietam National Battlefield, opposite David Miller’s famed Cornfield. They are not there for ambience—they mark the positions of Battery B, 4th U.S. Artillery, during its heroic early-morning stand at the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862.

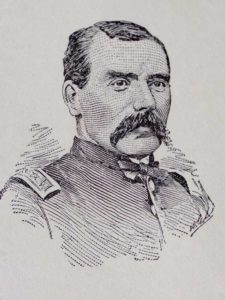

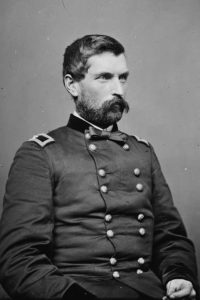

Though a Regular Army battery, the guns were not manned that day by tough, crusty veterans. In fact, only seven of the battery’s 100 members were Regulars. The rest were infantrymen detached from Brig. Gen. Abner Doubleday’s 1st Division, 1st Corps. The battery’s captain was 27-year-old Joseph Boyd Campbell, an 1861 West Point graduate. The other officer, 2nd Lt. James B. Stewart, was a Scottish immigrant, who enlisted in the battery in 1851 and rose steadily in rank. Five noncommissioned officers were Regulars, but the rest of the men came from the 2nd, 6th, and 7th Wisconsin; 19th Indiana; and 23rd and 35th New York Infantry.

On the morning of September 17, Battery B, armed with six 12-pounder smoothbores, followed Doubleday’s advance along the Hagerstown Pike toward the Miller Farm and unlimbered in a plowed field. The battery moved in support of Brig. Gen. John Gibbon’s 4th Brigade—the 2nd, 6th, and 7th Wisconsin and 19th Indiana, soon to earn the moniker Iron Brigade—which was spearheading the Union attack. Gibbon ordered Campbell to send forward Stewart’s two-gun section to a position in front of Miller’s barn, west of the pike.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]The Confederates kept coming, ‘fighting like mad men.’ But Battery B did too, paying a stiff price—nine killed and 31 wounded.[/quote]

By the time Stewart brought up his guns, Gibbon’s infantry was already fiercely engaged with Confederates just south of the Cornfield. Rising ground in front limited Stewart’s view, and Gibbon believed Stewart’s section would have a better field of fire if it moved forward to a slight ridge 100 yards farther south. He sent his aide, Lieutenant Frank Haskell, galloping to Stewart with orders. As Haskell rode up, Stewart noticed “large bodies of enemy troops coming out of the woods” several hundred yards in front to counterattack Gibbon. Since advancing seemed madness to Stewart, he told Haskell, “I wish you would give my compliments to the general and tell him, as I have cover for my men and horses, I do not think a move of seventy-five or one hundred yards is any advantage to artillery.” Haskell, however, didn’t interpret orders, he only delivered them. Stewart moved his guns forward as instructed.

After Stewart’s crews unlimbered and swung their guns into action, nearby Confederate infantry rose and poured fire into them, killing and wounding 14 of the 17 cannoneers and killing Stewart’s horse. Undeterred, Stewart ordered the survivors to take cover while he raced back to the Miller barn, where he had left his caissons. He ordered the drivers to help crew the guns. “The drivers did not want to leave the horses,” Stewart recalled, but the lieutenant made them dismount, with his section soon firing shrapnel into the flank of the Rebel counterattack. Gibbon brought the 19th Indiana and 7th Wisconsin up through the West Woods on Stewart’s right. The combined front, flank, and rear fire forced the Confederates to retreat.

Quickly assessing the damage that Stewart’s section had suffered in advancing, Gibbon ordered Campbell to bring up the rest of the battery. Campbell brought the guns down the Hagerstown Pike at a gallop and unlimbered to Stewart’s left, with the far left gun setting up within the pike itself. Years later, Major Rufus Dawes of the 6th Wisconsin wrote: “It was a great fault” to advance the battery where Gibbon ordered it, because the position was so exposed and forward. Gibbon might have agreed with the latter, but he placed Battery B at this point of danger because he wanted its firepower close to the front, where it could inflict maximum damage.

Campbell’s guns had no sooner unlimbered than the tide of battle abruptly turned. Brigadier General John B. Hood’s Division counterattacked from the West Woods and drove back Doubleday’s advance. To Campbell’s men, the first sign of major trouble was the sight of Doubleday’s infantry running back into the corn, quickly followed by Hood’s screaming troops. Campbell’s guns, loaded with canister, blasted the rapidly advancing Confederates. Artillery rounds containing more than 140 iron balls, each about one inch in diameter, “tore great gaps” in the enemy line but failed to break the charge.

The Confederates found cover by a fence lining the pike. Miller had allowed a dense growth of briars and brush to grow up along this fence, giving the Southerners excellent cover as they poured murderous fire into the Union battery. Campbell was hit in the neck, shoulder, and side; his horse shot seven times. Stewart took over, only to get hit by a spent ball. He concealed the wound, however, fearing he would lose command of his beloved battery.

Despite the canister fire, Hood’s men advanced to within 15 yards. Even when the battery fired double canister, the Confederates kept coming, fighting “like mad men,” according to one 7th Wisconsin soldier. But those in Battery B did, too. All but two were shot down at the gun in the road; 1st Sgt. John Mitchell was struck and injured as one of his guns recoiled. Nearly every gunner manning the two pieces on the right was killed or wounded, yet two men from that section reportedly crawled “on their hands and knees several times from the limber to the piece and loaded and fired those guns in that way until they had recoiled so far that they could not use them anymore.” Sergeant Joseph Herzog was so badly wounded that after being carried back to an emergency hospital he pulled his revolver out and “deliberately blew his brains out.”

Even General Gibbon helped crew a gun. When he noticed that the men working the piece in the road had the elevation screw improperly set so their canister charges flew harmlessly over the Confederates heads, he jumped off his horse and personally set the screw properly. The piece wreaked havoc in the enemy ranks while sending fence rails flying high into the air.

With Union infantry support, Hood’s attack was finally repulsed, but Battery B paid a stiff price—nine killed and 31 wounded, the highest loss of any battery during the battle. After the war, two members of the battery received Medals of Honor. With characteristic modesty, Stewart concluded his after-action report: “[T]he behavior of my men was all that could be desired.” Indeed.

Scott Hartwig writes from the crossroads of Gettysburg.