Author Bill Sloan’s article for World War II magazine was adapted from his book Undefeated: America’s Heroic Fight for Bataan and Corregidor, which received the Army Historical Foundation’s Distinguished Writing Award.

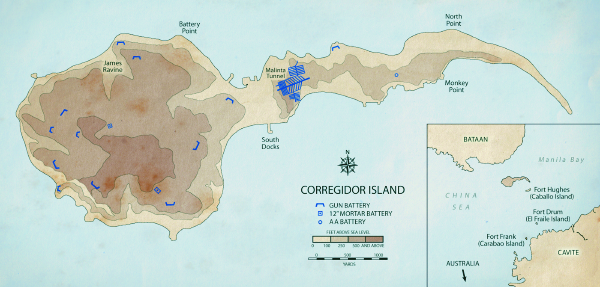

Beginning on the morning of April 10, 1942, the tadpole-shaped fortress island of Corregidor—known as the Rock to every American soldier, sailor, and Marine who served there—stood alone against the Japanese juggernaut that had just consumed the Bataan Peninsula two miles away. Japanese troops were busily moving 75 of the same powerful artillery pieces that had smashed the American-Filipino lines on the peninsula a few days earlier, positioning them to bear on Corregidor from what amounted to point-blank range.

Beginning on the morning of April 10, 1942, the tadpole-shaped fortress island of Corregidor—known as the Rock to every American soldier, sailor, and Marine who served there—stood alone against the Japanese juggernaut that had just consumed the Bataan Peninsula two miles away. Japanese troops were busily moving 75 of the same powerful artillery pieces that had smashed the American-Filipino lines on the peninsula a few days earlier, positioning them to bear on Corregidor from what amounted to point-blank range.

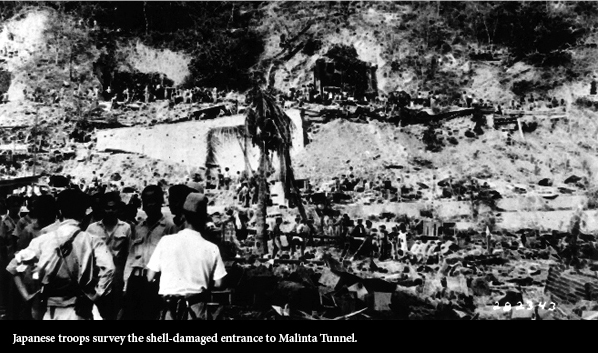

For many of the estimated 2,000 men who had escaped Bataan, Corregidor had long been a symbol of security and relative surcease from the rigors of the front line. Almost to a man, they believed that reaching the island gave them a ticket to a more comfortable, less hazardous existence than the one they had known for months. The Rock’s Malinta Tunnel complex—the army’s underground hospital, barracks, command, and storage facility, dug into Malinta Hill in the 1920s—remained basically unscathed despite daily air raids and intermittent artillery fire since mid-December 1941. Its garrison still received two reasonable meals per day instead of the wormy rice—or nothing—that had been standard on Bataan. Corregidor’s troops had access to clean water, laundry facilities, and showers. They didn’t have to worry about mosquitoes, or being bayoneted in their sleep.

Former B-17 crewman Ed Whitcomb’s reaction to Malinta Tunnel, after reaching Corregidor just moments ahead of a flight of enemy bombers, was typical. “Inside the tunnel, we greeted friends we hadn’t seen for a long time,” Whitcomb recalled. “We also found many officers and enlisted men in freshly washed and starched uniforms, living as comfortably as if the war had never caused them the slightest inconvenience…. We congratulated ourselves on successfully reaching this haven.”

But as Whitcomb and the others quickly learned, such assumptions were tragically premature. Corregidor’s tunnels were already overcrowded with troops and Filipino civilians, and most newcomers were assigned to beach defense. By dusk that first evening, Whitcomb found himself in charge of a Filipino crew and an antique wooden-wheeled 75mm gun, situated on a desolate corner of the island’s south coast called Monkey Point. “I slept on the ground beside my gun position that night,” he recalled, “but I felt more as if I were sleeping on a powder keg that was about to blow up.”

Whitcomb’s feelings were prophetic. Within a few days, Corregidor would become the most hellish five square miles on the face of the earth—a place that would make Whitcomb’s experiences on Bataan “seem like a Sunday School picnic.”

Karl King, a Marine toughened by weeks of front-line combat, failed to share Whitcomb’s rosy projections. He was immediately sent to the rocky beach near Battery Point on the island’s north coast to set up and man a .50-caliber machine gun position facing Bataan. “That afternoon, we found a navy supply dump that had an air-cooled .50, salvaged from a disabled PBY flying boat,” King recalled. “A two-wheel cart hauled the gun back to the company area, along with several boxes of ammo and the metal links for belting the ammunition. Looking for a place to set up our gun pit, we spotted a small earthen formation about 60 feet up the side of a cliff, [and] we dug in.”

The approximately 1,500 soldiers, sailors, and Marines whose job was defending Corregidor’s north beach did a commendable job preparing for the inevitable Japanese amphibious landings. But they were thinly spread over 3.5 miles of rock and sand, and most of their hastily constructed gun pits offered only minimal protection against attacks. “Enemy artillery spotters in observation balloons on Bataan had a clear view of the defensive positions,” King said. “Japanese 240mm howitzers, firing from Cavite and Bataan with high-angle trajectories, could drop rounds into every deep ravine and concrete gun emplacement.”

On the night of April 14, a 36-inch searchlight was set up near King, and lit to test its effectiveness in spotting Japanese invasion barges. None were in view, but the light drew instant attention from Japanese batteries on the peninsula. “Jap gunners must have had their hands on the firing lanyards waiting for the searchlight to come on,” King said. “It was on for all of 30 seconds before an artillery barrage…swept our position, snuffing out the light with a direct hit.”

Dodging shell bursts, King had made two trips to carry wounded to the protection of the ammo tunnel when a navy corpsman grabbed him by the arm. “Is that your blood on your pants leg, or is it from one of the wounded?” the corpsman asked. King felt a sharp pain and saw a piece of shrapnel lodged in his right leg. The corpsman removed the fragment and treated the wound, and King returned to his gun. (He was promoted to corporal the next day and awarded a Purple Heart, but the records would be lost in the mayhem that followed and neither would become official until six years later.)

The shelling that night was but a small taste of what was to come. Over the next three weeks, King recalled, “life on Corregidor could be compared to sitting in the middle of a bull’s-eye during rapid-fire target practice.” The attacks steadily increased in intensity until April 29, when the Japanese celebrated Emperor Hirohito’s birthday by launching the most

awesome display of firepower yet seen in the Philippines. It would continue day and night for six days.

As fate would have it, one of the final chances to evacuate some of the nurses, female civilians, older officers, and key military personnel occurred on that same day. Two 25-seat U.S. Navy PBY seaplanes were scheduled to land at about 11 p.m. on the 29th, in a sheltered area near the wreckage of Corregidor’s south docks. Twenty seats went to senior officers unlikely to survive as POWs, to a few civilian women, and to officers hand-picked by General Douglas MacArthur, who had left the Philippines seven weeks earlier to command the U.S. Army Forces in the Far East from Australia. The remaining 30 seats were filled from the 150-member nursing corps.

“We stood there and watched the seaplanes roar and take off and prayed they wouldn’t be hit,” recalled General Jonathan Wainwright, commander of all American and Filipino forces in the Philippines. “They sailed right off the water beautifully, pulled out over the side of Cavite beyond the range of the antiaircraft guns, and were enveloped in the night.” But only one of the planes would make it safely to Australia. The other was irreparably damaged as it landed for fuel on Mindanao; all its passengers would become POWs.

The last opportunity to escape Corregidor came on the night of May 3, when the submarine USS Spearfish slipped through the Japanese blockade to pick up critical military records and evacuate 25 passengers on its way to Australia. A handful of staff officers were sent aboard, some for health reasons, others to carry out specific assignments. The last 13 spaces went to women. The hospital’s chief nurse, Captain Gladys Mealor, was high on Wainwright’s evacuation list but refused to go. “I couldn’t see how anybody could walk off and leave all those wounded people,” she said. “I had enough faith in that old tunnel that I could make it if the Japs came in.” Wainwright was deeply touched. He would later say, “I considered—and still consider—this a truly great act of patriotism. She knew as well as I that she was signing her captivity warrant.” (Mealor was indeed captured, and held as a POW with the rest of the Corregidor garrison until the end of the war.)

When the conning tower of the Spearfish slipped beneath the surface of the bay, Corregidor’s last physical link with the outside world was broken.

Life deteriorated into sheer bedlam for the 12,000 military personnel on Corregidor as the enemy’s ceaseless bombardment ate away at the infrastructure that had previously kept life bearable in Malinta Tunnel. The bone-rattling enemy attacks frequently plunged them into total darkness, and corpsmen were routinely called upon to hold flashlights when the hospital operating room lost power during surgery. Drinking water was in short supply, and headquarters was steadily losing communication with every outpost beyond the tunnels. The situation worsened as thousands of Filipino civilians, forced from their homes on the island, sought refuge below ground. “They relieved themselves where they stood,” wrote Colonel John R. Vance, one of Wainwright’s staff. “For food, they were issued canned goods, and the empty and dirty containers were added to the human filth on the pavement.”

In a physical sense, much of the shelling was overkill, since there was little left to destroy on the island’s surface. But casualties increased among the beach defenders, and the incessant pounding took a heavy toll on morale—including inside the physical safety of the tunnels. “Almost everyone was overwhelmed by the psychosis of doom,” Colonel Vance wrote. Scattered incidents of self-inflicted gunshot wounds and suicides were reported.

No final tally exists of the number of bombs and artillery rounds that struck the Rock, but during this time it was the target of more than 300 full-scale Japanese air raids and hundreds of thousands of heavy artillery rounds—up to 16,000 on a single day. Early on the morning of May 2, at the start of a typical combined enemy air-artillery bombardment, two of Wainwright’s staff officers began counting the number of explosions. They determined that on average, at least a dozen bombs and shells hit the island every minute for five straight hours—a total of 3,600 rounds armed with an estimated 1.8 million pounds of explosives. After that, they stopped counting.

Fourth Marines Private Roy Hays, and every other defender of Corregidor’s eastern beaches, knew that time was running out. Tantalizing rumors of reinforcements had been pounded to dust by the Japanese. But nothing drove home the truth with greater finality than the sight before Hays’s eyes late on the night of May 5. Out of the darkness, Japanese landing barges were at last approaching the beach at North Point.

“God, how many of ’em you reckon there are?” whispered Hays’s buddy Tommy, who was manning the machine gun next to him. “A lot more than there are of us,” Hays replied. Five dozen American and Filipino defenders were spread out around Hays’s position. Hays and Tommy had the only two machine guns—water-cooled .30-caliber World War I relics—but several men had Browning automatic rifles (BARs). Others had regular rifles, mainly bolt-action 1903-model Springfields or old British Enfields. Others had only pistols. Hays kept listening for his order to fire, until he saw the closest barges bump against the beach. “Christ, if we don’t hit ’em now, they’ll be right on top of us,” he told his ammo handler. Then he turned and yelled “Fire! Open fire!” down the line.

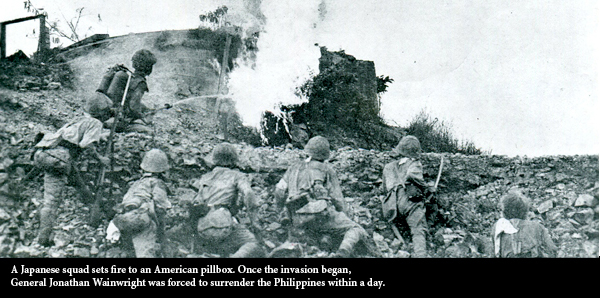

“I truly believe we killed every Jap on the beach,” Hays would say some 68 years later. “I don’t think any of them got ashore alive. At first light, we saw eight landing barges bobbing in the surf, and there was no sign of life on any of them.” According to best estimates, all but 800 of the first wave of 2,000 Japanese invaders died before they reached dry land. It was among the Fourth Marines’ finest hours, but it wasn’t enough to halt the invasion.

On May 6, Wainwright received a stirring message from President Franklin D. Roosevelt himself: “During recent weeks, we have been following with growing admiration the day-by-day accounts of your heroic stand…. In spite of all the handicaps of complete isolation, lack of food and ammunition, you have given the world a shining example of patriotic fortitude and self-sacrifice.” Wainwright deeply appreciated the president’s sentiments, but the tone made clear that Corregidor was on its own.

Corregidor’s eastern tail, where Private Hays and his comrades had repelled one of the Japanese landings the night before, had vanished behind a thick veil of smoke and dust. All but one or two of Corregidor’s 23 coastal artillery batteries had been silenced, eliminating the garrison’s ability to strike back against the enemy’s big guns on Bataan. Along the length of shore facing Bataan, only a handful of machine gun emplacements still survived. Everything else had been obliterated.

Most of the Americans who had met the Japanese in hand-to-hand fighting along the north beaches were now dead or wounded. There were no more troops left to send. Bodies were piling up in Malinta Tunnel outside the hospital section, awaiting burial until the bombardment slackened—if it ever did. Countless casualties littered the beaches and ravines along the north side of the island.

And now, as if to confirm the finality of the situation, came the news that three Japanese tanks were grinding their way toward the main entrance to Malinta Tunnel. With nothing more powerful than rifles, a few light machine guns, and moldy 1918-vintage hand grenades, the defenders had not a single weapon capable of slowing down—much less stopping—a tank. Wainwright could envision the resulting bloodbath should the tanks fire their cannons down the main tunnel, where scores of nurses were treating more than 1,000 sick and wounded men amidst vast stores of munitions and gasoline.

At 10 a.m., word reached Wainwright that the Japanese were steadily driving more tanks against dogged but failing resistance toward Malinta Tunnel. He summoned General Lewis Beebe, his chief of staff, and General George Moore, commander of the Manila Bay harbor defenses. “Maybe we could last through this day, but the end must certainly come tonight,” Wainwright told them. “It would be better to clear up the situation now, in daylight. What do you think?”

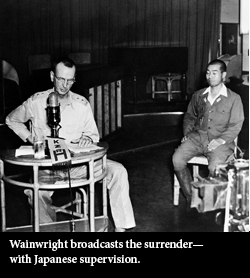

“I think we should send a flag of truce through the lines right now,” Beebe said. “There should be no delay,” Moore added. Wainwright sighed. “Tell the Nips we’ll cease firing at noon,” he said. After Beebe and Moore left to broadcast the surrender message, Wainwright scribbled a final note to President Roosevelt. “It is with broken heart and head bowed in sadness, but not in shame, that I report to Your Excellency that I must go today to arrange terms for the surrender of the fortified islands of Manila Bay…. There is a limit of human endurance, and that limit has long since been passed…. Goodbye, Mr. President.”

Army radio operator Irving Strobing was the last to tap out a message from Corregidor, aimed at anyone listening. “Tell [my brother] Joe, wherever he is, to give ’em hell for us. My love to you all. God bless you and keep you. Sign my name, and tell mother how you heard from me. Stand by.” After that, there was only silence from the Rock.

Marine Private Ernest J. Bales learned of the surrender when a runner managed to reach his position in James Ravine, where he was assigned to one of four .30-caliber machine guns. At that moment, Bales was huddled with six other Marines and soldiers in a trench only a few dozen yards from the water’s edge. All of them were waiting for something—but not surrender. “We’re throwing in the towel,” the runner said, gasping for breath. “You’re supposed to destroy all weapons.” For a long moment, Bales could only stare at the runner in stunned silence. “It was really hard to take,” he recalled. “Was this what we’d spent all these damned days and nights dodging bombs for? I couldn’t believe it.”

“Who the hell says so?” demanded one of the other men in the trench, pointing his pistol at the soldier who had delivered the message. “It’s straight from Wainwright,” the runner said. “It’s on the level.” Bales would recall many years later, “I honestly think this guy might’ve shot the runner if some of the others hadn’t grabbed his arm and wrestled the gun away.”

Private Ben Lohman of the Second Battalion, Fourth Marines did as he was told and destroyed his BAR. But he soon regretted it, because the Japanese gave no indication of honoring the so-called cease-fire. “We had plenty of ammo for the BARs,” he recalled. “I could see the Jap barges coming in, and I’d had a chance to fire on some of them with the BAR. Once I’d wrecked it, though, it was useless.” Lohman and his mates huddled low in their hand-dug gun pits while enemy artillery rounds poured in with no discernible letup. “We didn’t know what the hell was going on,” he said. “If the fighting was over, the Japs didn’t seem to have gotten the word. I’d say they had us by the ass, and they knew it and didn’t care.”

The persisting hostilities stemmed from two causes. One was Japanese determination to use the Corregidor surrender to take full possession of the Philippines. The other was a last-gasp attempt by General Wainwright to avoid exactly that.

Nearly two hours passed before the Americans detected a noticeable decline in the shelling outside. Wainwright recruited a young Marine, Captain Golland L. Clark, to go in search of a senior Japanese officer to relay the surrender message in writing. Another hour went by before Captain Clark returned with discouraging news. “He won’t come to see you, General,” Clark said. “He insists that you go and meet him.” When Wainwright and his party ventured forth under a flag of truce, they were stopped by a wiry young lieutenant “reeking with arrogance,” as Wainwright later put it. “He identified himself as Lieutenant Uramura,” the general recalled, “and before I had a chance to speak, he barked in English, ‘We will not accept your surrender unless it includes all American and Filipino troops in the whole archipelago!’” This marked the beginning of a long, frustrating day for Wainwright and his staff.

Wainwright barked back at Uramura that he had no intention of negotiating with a lieutenant, and in due time Colonel Motto Nakayama—the non-English-speaking officer who had accepted the surrender of Bataan—arrived on the scene. With Uramura serving as interpreter, Wainwright said he could surrender only the four islands—not the Mindanao-Visayan Islands far to the south, where some 25,000 American and Filipino troops could keep up the fight after Corregidor’s surrender.

This sent Nakayama into a rage, and he repeated that no surrender would be accepted if it didn’t include all U.S. forces in the Philippines. Wainwright reacted with his own flash of anger, and declared he would only negotiate with General Masaharu Homma, commander of the Philippines Invasion Force. After a brief interval of hostile silence, Nakayama agreed to take Wainwright to Homma’s headquarters on Bataan.

Accompanied by his staff officers, Wainwright arrived on the peninsula at 4 p.m., but Homma made a point of keeping them waiting for two hours before summoning them to his headquarters. Meanwhile, Japanese forces amplified the demand for total American capitulation in the Philippines by sending waves of bombers across the length of Corregidor. Flying from east to west, they blanketed the tortured island with scores of new explosions while the American surrender party looked on. They were spared the sight at Malinta Tunnel, where Japanese tanks smashed the last defenses and lined across the east entrance. Soldiers armed with flamethrowers also deployed across the entrance. The message was crystal clear: if the surrender wasn’t consummated to the Imperial Japanese Army’s satisfaction, wholesale slaughter would quickly ensue.

At about 6 p.m.—seven hours after the surrender message was first broadcast—Wainwright’s party was driven to Japanese headquarters on Bataan for another hour-long wait before Homma arrived in a shiny Cadillac. When the interpreter finished reading Wainwright’s signed surrender document, Homma spoke sharply to the interpreter. “General Homma replies that no surrender will be considered unless it includes all United States and Philippine troops in the Philippine Islands.” Wainwright and Homma argued back and forth for several minutes, until Homma terminated the argument with this threat: “Hostilities against the fortified islands will be continued unless the Japanese surrender terms are accepted!”

At about 6 p.m.—seven hours after the surrender message was first broadcast—Wainwright’s party was driven to Japanese headquarters on Bataan for another hour-long wait before Homma arrived in a shiny Cadillac. When the interpreter finished reading Wainwright’s signed surrender document, Homma spoke sharply to the interpreter. “General Homma replies that no surrender will be considered unless it includes all United States and Philippine troops in the Philippine Islands.” Wainwright and Homma argued back and forth for several minutes, until Homma terminated the argument with this threat: “Hostilities against the fortified islands will be continued unless the Japanese surrender terms are accepted!”

“I was desperately cornered,” Wainwright recalled in his memoirs. “My troops on Corregidor were almost completely disarmed, as well as wholly isolated from the outside world.” The blood of over 10,000 men and women would be on his hands unless he yielded to the demands. “That was it,” he wrote years later. “The last hope vanished from my mind.”

Wainwright returned to Corregidor, where he typed up and signed a new surrender document. It was after midnight when, as Wainwright put it, “the terrible deed was done” and he was taken under guard to the west entrance of the tunnel, past hundreds of his troops. Many of them waved or reached out for Wainwright’s hand. Others patted him on the shoulder, repeating the same reassurance. “It’s all right, General,” they said. “You did your best.” Private Edward D. Reamer was standing near the tunnel entrance, within 40 feet of Wainwright as he passed. “I could see tears on Wainwright’s cheeks,” Reamer recalled. “You couldn’t look in any direction outside the tunnel without seeing a dead body. One guy was holding a Tommy gun with half his head blown off. Those guys fought right up to the tunnel, right up to the headquarters.”

Tears were still streaming down Wainwright’s face when he reached General Moore, who tried to assure him that he’d taken the only conceivable course. “But I feel I’ve taken a dreadful step,” Wainwright said brokenly.

On hearing the news of the surrender, MacArthur issued a brief statement. “Corregidor needs no comment from me. It has sounded its own story at the mouth of its guns. It has scrolled its own epitaph on enemy tablets, but through the bloody haze of its last reverberating shots, I shall always seem to see the vision of its grim, gaunt, and ghostly men.”

On hearing the news of the surrender, MacArthur issued a brief statement. “Corregidor needs no comment from me. It has sounded its own story at the mouth of its guns. It has scrolled its own epitaph on enemy tablets, but through the bloody haze of its last reverberating shots, I shall always seem to see the vision of its grim, gaunt, and ghostly men.”

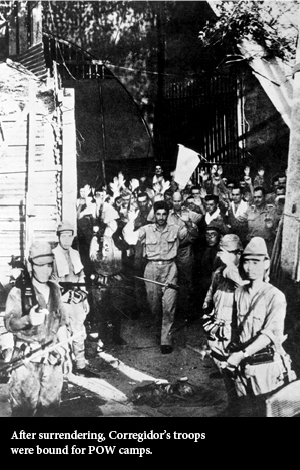

On May 7, 1942, almost five months to the day since the first Japanese attacks, all organized American resistance in the Philippines officially ended. For the 11,000 men and women who survived the battle for the Rock, a longer, deadlier, and still more horrific struggle for survival loomed ahead.

Bill Sloan has written and reported on many of the major news events of the past half-century, and was nominated for a Pulitzer during his 10 years at the Dallas Times Herald. Sloan is the author of 15 books, including 6 military histories focusing on World War II and Korean War action in Asia and the Pacific. The latest of these is Undefeated: America’s Heroic Fight for Bataan and Corregidor, released this spring by Simon & Schuster. Hell in the Pacific, a memoir by former Marine sergeant Jim McEnery with Sloan as co-author, will be published this August to coincide with the 70th anniversary of the Battle of Guadalcanal.