Want to buy a belt plate? A forage cap? This relic show has them, and more

Steps from a chilling amputation display, militaria dealer Larry Hicklen wore a mile-wide grin. But the sight of a 19th-century prosthetic limb or the image of a one-armed veteran wasn’t what has him jazzed as he stood on the ground floor of the Middle Tennessee Civil War Show.

It was the sea of tables spread out before him at Franklin’s sprawling Williamson County Agricultural Expo Center last December, where roughly 550 dealers from 40 states—and two from overseas—offered for sale artifacts, oddities, and everything in between. And it was the hundreds of history buffs shouldering past each other in crowded, “excuse me” aisles on two floors, gawking at muskets, munitions, and more.

In its 33rd year, the two-day event founded and owned by Hicklen normally vied with a Mansfield, Ohio, show held every May for bragging rights as “The Greatest Civil War Show in America.” The Mansfield show was canceled because of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Did Hicklen ever think the Franklin show would become such a huge deal in 1986?

“Hell no,” the 68-year-old Tennessee native told me.

In normal years, dealers come to Franklin every December eager to display collections and to bond with peers. A “Civil War social,” Hicklen calls the show. The event, first held in nearby Nashville, usually takes place at the same venue as Franklin’s annual rodeo. Maybe that’s why it’s so easy to lasso a story or two at this carnival / swap meet / temporary museum / marketplace.

Though it isn’t clear whether the 2020 show will go off as planned, the dealers are looking forward to telling stories. At least one of those tales may make you cringe.

Boom!

The firing of a replica cannon by reenactors outside reverberated through the Expo Park building shortly after the start of the show at 10 a.m. December 7, 2019. Unofficial colors for the event are white and gray: Attendees and dealers are overwhelmingly Caucasian, over 50, and male, leading one to wonder about its long-term viability.

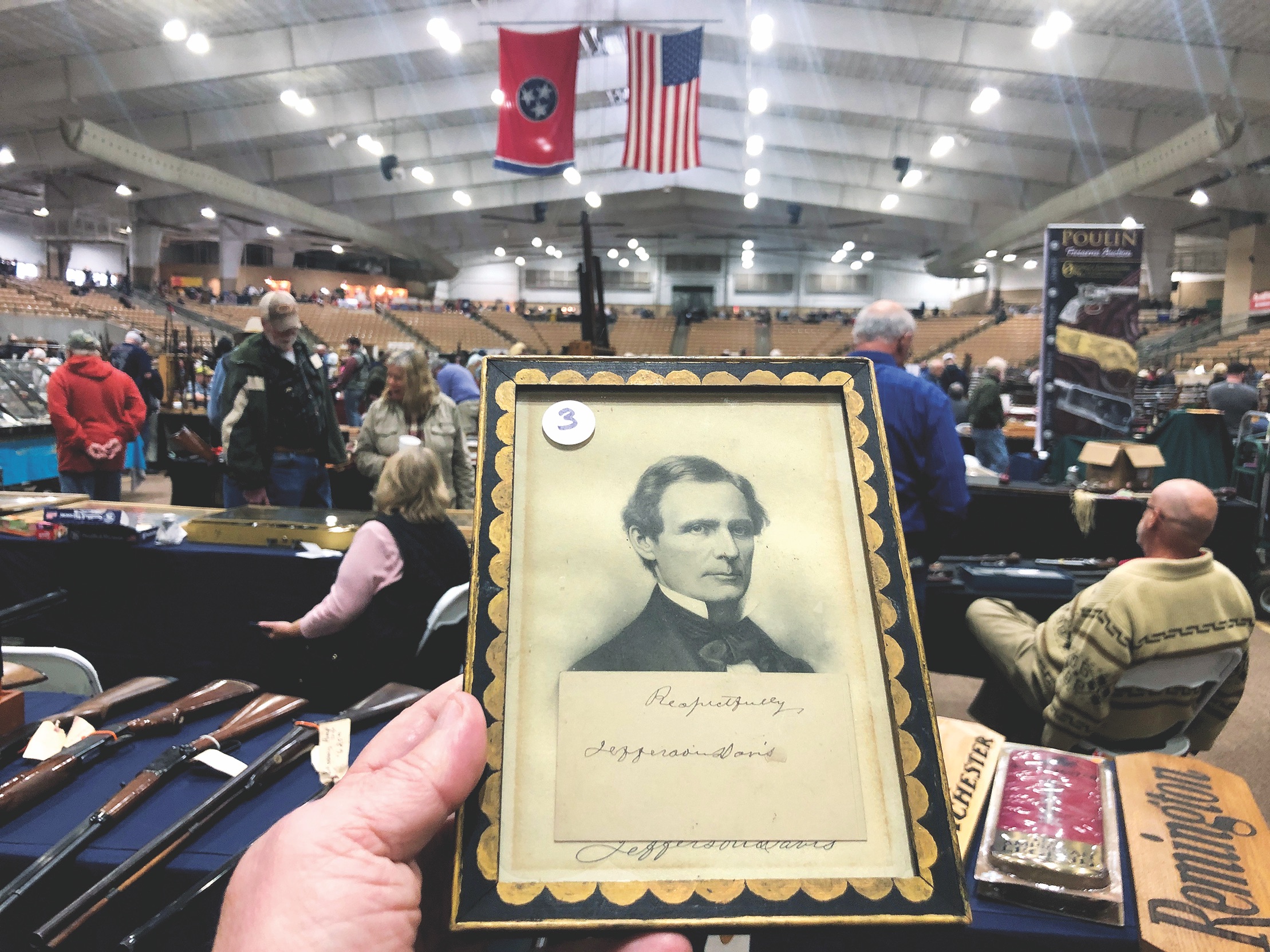

The artifacts on sale at the last show brought lots of interested potential buyers. If you wanted to spend your inheritance from grandma, you could fork over nearly $24,000 for the half-plate ambrotype of a Confederate officer who was wounded and captured at Gettysburg. Not in your budget? Perhaps the Jefferson Davis clipped signature ($1,000) would pique your interest.

At his display table, 71-year-old Mike Parker, a retired building supplies salesman from Birmingham, Ala., offered for sale for 150 bucks a massive cannon ball purchased in an antiques store in Corinth, Miss., in 1978. Filled with concrete and broken rebar, it was used by a previous owner as a decoration for a mailbox top. “The Widow Maker,” I called it, tongue planted firmly in cheek.

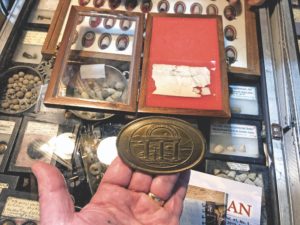

A show participant for more than 30 years, Parker pointed out his favorite relics: Confederate Selma Arsenal and Union .58-caliber bullets that collided “perfect nose to nose” at Fort Blakely, Ala. “Took a friend over 40 years to sell it to me,” he says. Parker had an affinty for the two ounces of lead—asking price $2,000—which he kept in a small display case with a plaque on the front that reads, “One in a Million.”

“I’m afraid,” Parker says, ruefully, “someone will buy it.” (Someone did.)

Parker got hooked on relic hunting when his father took his family to Vicksburg in 1958. Scratching at the Mississippi soil, he uncovered a bullet. The next year, he actively began hunting for relics. He used to have a 2 ½-gallon bucket filled with Civil War bullets, two-thirds of which he gave to kids.

Two of Parker’s great-great-grandfathers served in the Army of Northern Virginia—in the 14th and 6th Alabama. Both fought at Gettysburg, where, on a trip in 1976, Parker visited with a farmer who used gun barrels from the battle as part of his fence rail. The man presented his Southern visitor with a unique gift: an authentic Gettysburg Federal knapsack he had been using as a feed sack.

Amid tables filled with muskets, bullets, and artillery shells, Chris Utley of Spring Hill, Tenn., offered for sale something unique: replica Civil War handkerchiefs. Who knew?

“I was looking to do something no one else did,” says the longtime reenactor, whose day job is investigative director for an insurance company.

Utley owns five original soldier handkerchiefs—including one that belonged to 25th Massachusetts Sergeant Ira Lindsey, a 38-year-old shoemaker and machinist who was killed at the Battle of Cold Harbor.

All Utley’s reproductions are copies of Civil War soldier handkerchiefs found in private collections or museums. He says he mostly caters to the “authentic crowd”—especially reenactors.

As we visited, local lawyer Adam Wood stopped by. He has bought nine of Utley’s handkerchiefs. He says they make him look distinctive in court. “I generally stick to Southern ones, but every once in a while, I get a Yankee handkerchief,” he said with a laugh.

Leaning on his cane, 62-year-old Richard McCardle was eager for someone—anyone—to take a 100-pound U.S. Navy Parrott shell off his hands. The gruff Alabamian said he acquired the behemoth from an old-time relic hunter named “Mr. Charlie,” who discovered it decades ago in the vicinity of Fort Hell at Port Hudson, La.

“Tired of carrying it around,” says McCardle, who’s willing to knock off a few bucks from the $750 price. One consolation for a prospective owner: This beast slimmed down to roughly 80 pounds after making its long-ago impact.

McCardle, whose relic hunting career began at 14 when he found a bullet at Shiloh, specializes in one-of-a-kind items. Behold at the dealer’s table a “very rare” .69-caliber Confederate exploding bullet ($650) and a Confederate assistant surgeon’s carved Meerschaum pipe ($3,800).

“How many people here,” he said, scoffing, “got a doctor’s pipe from a guy in the 48th Mississippi? I love stuff like that.”

McCardle also offered up what he says is another rarity: the “only known” Alabama VC belt plate from Gettysburg. The price tag reads $5,500 for the mangled piece of lead, unearthed by a relic hunter in 1996. “But for you today only,” he said, ever the dealmaker, “it’s yours for $5,000.” When a customer says he must check with a higher power, McCardle says, “Give me the phone, I’ll call her.”

The former U.S. Army tanker enjoys bantering with visitors. He likes the show venue, too. “Only problem I have with this place is the cow shit,” he says, pointing with his cane to the remnants of rodeo poo behind his table.

Nearly 8,100 miles from home in New Zealand, easily the farthest traveled by any show participant, Englishman Tony Trueman pitched his replica cannon barrels. In Nashville to sell marina equipment, he figured a stop at the Franklin show would be worth his time —even though he knows only a “general outline” of the Civil War.

Trueman said he has sold about 1,000 replica cannon over the past five years —to museums, theme parks, escape rooms, Civil War enthusiasts, and the “pirate community.” That sounds kind of ominous, but then he eased my fears by showing me a photo of a pirate-themed amusement park in Sweden.

Beads of sweat on his forehead and a pipe clenched in his mouth, Chris Trimble eagerly talks about the priceless green frock coat displayed at his booth. When he first saw it at an estate sale, the longtime Virginia antiques dealer thought it was a doorman’s uniform or part of a theatrical costume.

“Maybe it was for Halloween,” he says. “It had gold braids and tassels affixed to it. Perhaps some hippies from the 1960s used it.”

When he examined the coat more carefully, Trimble noticed a Civil War-era button. Further investigation revealed that the frock coat was worn during the war by Captain Abraham Wright of Company A of the 2nd U.S. Sharpshooters—the famed unit founded by Hiram Berdan. Along with the coat—put your credit card away, it’s not for sale—he displays a beautiful, full-plate tintype of Wright, also purchased by Trimble at the same estate sale.

From behind his booth, Trimble pulled out another relic—it belongs in the “top 1 percent of the best of the best,” he insists. The pristine, non-dug, oval Georgia state seal box plate was picked up by a soldier at the first organized battle of the war, at Philippi, Va., on June 3, 1861. The relic, along with a note about its discovery, was sent home by Union officer James Forsythe to his wife.

For those with a limited budget, Trimble offers modestly priced relics. Civil War-era pipes—some broken, some not—are available for as little as five bucks.

Steps from founder Hicklen’s table, we find the Franklin show’s piece de resistance of weirdness. In his display on Civil War amputations, dealer Wayne Williams has the artificial limb of his great-great-grandfather, a Union soldier whose right arm was amputated after he was shot twice at Petersburg in April 1865.

Williams has the bullet that did the damage, too.

According to Williams family lore, Alvah Williams of the 208th Pennsylvania sat by a tree for three days after he was wounded. Then he went to a field hospital, where the bullet fell out on the operating table. “I want to take that,” he said.

Wayne’s father, founder of the Mansfield Civil War Show, displayed the prosthetic arm and bullet on a wall for years in their house in Ohio. The unusual items livened conversation when Wayne’s friends saw them.

“They were grossed out,” he says. “They had never seen anything like it.”

Never seen anything like it.

An apt description, too, for one of America’s greatest Civil War shows. ✯

John Banks is the author of the popular John Banks’ Civil War blog. He lives in Nashville, Tenn.