Amid the bitter winter of 1950 there was little reason to be optimistic about the outcome of the Korean War. By late December American-led United Nations troops were two months into a demoralizing full-scale retreat. In late October the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army (PVA) had crossed the Yalu River to join the North Korean People’s Army (KPA) in a massive offensive against U.N. Command forces under Gen. Douglas MacArthur. Relentless assaults by Chinese troops during the retreat from the Chosin Reservoir, in North Korea’s mountainous far north, particularly devastated the coalition troops.

By the outset of 1951 the PVA had pushed U.N. forces back across the 38th parallel. Given their vast numerical superiority, the Chinese seemed unstoppable as they pushed south. On January 7 PVA and KPA troops captured the South Korean capital of Seoul for the second time. The situation became so dire that Allied brass made contingency plans to withdraw all U.N. forces to the Pusan Perimeter, site of the close-run battle the previous September.

In mid-January, however, the Chinese offensive ground to a halt due to increasingly heavy losses and overstretched supply lines. The U.S. Eighth Army, under newly arrived Lt. Gen. Matthew Ridgway, reached the Han River south of Seoul on February 9 after a series of successful offensive attacks aptly code-named Operation Thunderbolt. To thwart further advances by communist forces east of Seoul, he established a defensive line between Chipyong-ni and Wonju.

It was do or die for the U.N. coalition.

Thirty-five miles east of Seoul, Chipyong-ni straddled an important crossroads controlling movement through the Han River Valley, a vital transportation corridor on the central Korean peninsula. The deserted village lay along a single-track railroad stretching from Wonju, 20 miles southeast of Chipyong-ni, to Seoul. If it fell, the entire Eighth Army front would be in a dire position.

Recognizing control of Chipyong-ni was the linchpin to stopping the Chinese advance, Ridgway ordered the 23rd Regimental Combat Team (RCT) of the U.S. 2nd Infantry Division to hold it at all costs. Leading the unit was Col. Paul L. Freeman Jr., a Philippine-born West Point graduate who had served in the China-Burma-India theater in World War II and had spirited his regiment through the retreat from Kunu-ri in November. The 23rd RCT had just come off a hard-fought victory against the Chinese at the February 1 Battle of the Twin Tunnels.

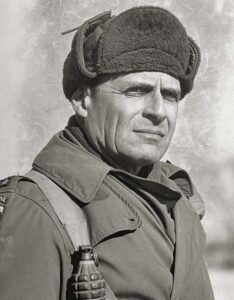

Despite having been reduced to 75 percent combat effectiveness, the battered unit moved 3 miles across rough terrain through snow and ice into Chipyong-ni on February 3. Attached to the unit were the 1st Ranger Company, the 37th Field Artillery Battalion, elements of the 503rd Field Artillery Battalion, several tanks, mobile anti-aircraft guns and a company of combat engineers. Joining the Americans was the coalition’s French Battalion, led by Lt. Col. Raoul Magrin-Vernerey. Better known by his nom de guerre, Ralph Monclar, he was a battle-tested veteran of the French Foreign Legion and World War II general who had accepted a demotion in order to lead the battalion. Freeman commanded a force of 4,500 men in all.

While eight prominent hills around Chipyong-ni offered excellent defensive positions, the tactically savvy Freeman realized his limited force could not adequately cover the 12-mile ridgeline. Instead, he made the seemingly counterintuitive decision to concentrate his men within a tight perimeter on the low-lying terrain surrounding the village. Freeman knew, however, the PVA’s lack of air superiority and long-range heavy artillery would disadvantage the enemy on higher ground. Moreover, his meticulous selection and organization of tight defensive positions made the perimeter virtually impregnable—as long as air resupply remained possible.

On February 11 the Chinese launched their Fourth Phase Offensive, striking the U.S. X Corps at Wonju and Hoengsong and forcing two divisions to withdraw under heavy pressure. Realizing his position was exposed and under threat of encirclement, Freeman requested permission to withdraw 15 miles south to Yoju. His request was approved by division and corps commanders but adamantly refused by Ridgway, who resolved to hold Chipyong-ni and would support the 23rd RCT even if he had to send the entire Eighth Army.

Freeman also had the backing of his men. “When Col. Freeman said at Chipyong, ‘We’re surrounded, but we’ll stay here and fight it out,’ we supported him with enthusiasm,” recalled Capt. Bickford Sawyer of Company E. “There was never a doubt in our minds. We knew we were going to succeed.”

Chinese troops soon cut off both main roads to the village, isolating the 23rd RCT some 20 miles beyond friendly lines. Determined to hold out, Freeman strengthened his defenses in preparation for the inevitable siege.

On the afternoon of February 13 several Chinese regiments amassed around Chipyong-ni. American artillery and airpower held them at bay for the moment. As darkness settled over the valley, temperatures dropped to near freezing. Finally, at 10 p.m. the American and French positions began taking intense mortar, artillery and small-arms fire from three sides. The 1st Battalion, manning the northern perimeter, bore the brunt of the initial barrage.

Especially hard hit were the men of Company C, tasked with defending Route 24, the main road into Chipyong-ni. Around midnight the crisp air resounded with the deafening clamor of bugles, whistles, bells and battle cries as wave after wave of Chinese charged the northern perimeter, quickly followed by equally fierce attacks on 2nd Battalion, in the south, and Monclar’s French Battalion, in the west.

The fighting was intense but brief as the enemy probed the defenses around the village. At 1 a.m. on the 14th they renewed their assault from the north, but 1st Battalion managed to hold its ground, forcing the Chinese to dig in after an hour of heavy fighting. The defenders found no reprieve, as the enemy continued to probe the perimeter, hurling themselves into the fight with total disregard for their lives.

On the eastern perimeter 3rd Battalion’s Company K fought off several mass frontal assaults, inflicting horrific losses on the enemy. The fighting in that sector became so intense that coalition ambulances could not get through to evacuate the wounded. At 2 a.m. on the western perimeter determined French defenders occupying Hill 345 beat back waves of Chinese infantry surging uphill. In the storied encounter French legionnaires responded with a frenzied bayonet charge to the accompaniment of a hand-cranked siren that sent the attackers fleeing in fear and confusion. At one point sustained attacks up north forced Company C to withdraw, but rallying U.S. troops quickly launched a counterattack and regained all lost positions.

In the south 2nd Battalion’s Company G came under heavy attack for some 90 minutes and by 4 a.m. was in danger of being overrun. American tanks arrived in time to provide decisive armored support. An after-action report summarized the company’s desperate position:

Each succeeding wave, stronger than the preceding one, was being thrown at Company G at about 10-minute intervals.…Company G men were being killed and wounded by intense machine-gun and mortar fire, creating gaps in the line of foxholes on the MLR [main line of resistance]. The infantrymen fought like demons. They could see each wave in the light of illuminating flares, coming closer and closer, and knew that eventually certain death awaited them, but they never faltered. They remained at their guns, shooting grimly until the bitter end.

With the coming of daylight the Chinese knew they would be exposed to strikes by American aircraft. In those predawn hours the PVA carried out one last major assault against 3rd Battalion in the east, but the defenders managed to beat them back with a deadly combination of artillery, mortar and small-arms fire. At 7:30 a.m. Chinese buglers sounded the call to withdraw. That night the U.N. garrison had suffered some 100 casualties. Freeman himself had been struck in the leg by shrapnel from an enemy mortar, but he refused evacuation. He’d remain in the fight alongside his men.

In the light of day on the 14th the constant presence of U.S. aircraft forced the Chinese into hiding. The American and French troops used the opportunity to rebuild defenses, reposition artillery and call in airdrops for resupply.

Farther south the U.S. 5th Cavalry Regiment, under Col. Marcel G. Crombez, organized a relief force to break through to Chipyong-ni. Task Force Crombez managed to cross the Han River and approach within 8 miles of the garrison before running up against increasingly heavy resistance. Fighting its way toward Chipyong-ni from the southeast, the 27th British Commonwealth Brigade also bogged down in the face of enemy resistance. The 23rd RCT would have to hold on a while longer.

The attacks picked up in intensity. That evening Chinese mortars and artillery rained down shells on the besieged garrison. At 8:30 p.m. the bombardment lifted as massed Chinese infantry launched savage attacks all along the line, particularly against 2nd and 3rd Battalions. Chinese soldiers again breached the perimeter, this time in an eastern sector held by Company I, 3rd Battalion. And again the Americans quickly recovered the position, as Company I launched a close-quarters counterattack supported by Companies L and M. The Chinese launched two major assaults against Company K, but the eastern perimeter held firm.

By 1:30 a.m. on the 15th the Americans and French were experiencing critical shortages in ammunition as pressure continued to mount all along their perimeter. An hour later Chinese infantry broke through Company G to the south. The 1st Ranger Company, along with elements of Company F and the remnants of Company G, launched a desperate counterattack but were gradually driven back in vicious hand-to-hand fighting. The 23rd RCT committed Company B and its last remaining reserve platoon to the counterattack, but intense enemy fire pinned down the Americans. It was the defenders’ darkest moment.

As dawn broke on February 15, however, U.S. aircraft once again took to the skies, relentlessly attacking the exposed communist forces and delivering precious supplies to the beleaguered garrison. At 2 p.m. the defenders called in napalm strikes on the entrenched Chinese, buying enough time for Company B to recapture all lost positions. Second Lt. Robert Evans shared a grim recollection of the carnage:

We were ready to open defensive fire against the sons of Chinese rice farmers climbing up to meet us when a ground-support plane came over the ridge from behind and dropped a belly tank of napalm on the ascending army, a gelatinous river of horror burning all in its path. Some of us tried to fire at the human torches to end the pain: useless.

At 4:30 p.m. the exhausted but victorious men of Company B could see tanks approaching from the south, signaling the arrival of Task Force Crombez. An hour later the relief column rolled into Chipyong-ni as Chinese troops fled from the field under heavy fire from aircraft and 23rd RCT artillery.

At Chipyong-ni 4,500 men had fought off elements of five Chinese divisions estimated to number some 25,000 troops. Coalition forces recorded just 52 killed, 259 wounded and 42 missing. The U.N. troops counted 4,946 enemy dead around the perimeter—exceeding the entire strength of the 23rd RCT.

The victory galvanized the Army, restoring the morale and fighting spirit of the Americans, while shattering the communist offensive. Chipyong-ni represented the high-water mark of China’s incursion into Korea. Over the following weeks U.N. forces advanced north, recapturing Seoul on March 14th and pushing communist forces back across the 38th parallel, the starting line of the war a year earlier. For their heroism the 23rd RCT and its attached units were awarded the Distinguished Unit Citation (present-day Presidential Unit Citation). Freeman received the Distinguished Service Cross for his leadership at the Twin Tunnels and Chipyong-ni. His innovative tactical strategy lives on as a prototype for defense while encircled and outnumbered. MH

Daniel Ramos is a researcher and freelance writer on military topics who works for the National September 11 Memorial & Museum in New York. For further reading he recommends Leadership in the Crucible: The Korean War Battles of Twin Tunnels and Chipyong-ni, by Kenneth E. Hamburger, and Crossroads in Korea: The Historic Siege of Chipyong-ni by T.R. Fehrenbach.