In 1850 Hong Xiuquan—a despondent Chinese scholar who had flunked the imperial civil service examination multiple times—launched the world’s most costly Christian rebellion. Well, nominally Christian, anyway; Hong claimed to be the literal younger brother of Jesus Christ and announced he’d been chosen to save the Chinese people through creation of the Taiping Tianguo (Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace). He proclaimed himself king of this celestial dynasty and called on followers to overthrow China’s imperial Qing dynasty.

By the time the dust settled, upward of 20 million civilians and soldiers had died of disease, starvation or in battle. Ironically, it took an American Christian to create an army instrumental to the defeat of the only so-called Christian rebellion in Chinese history.

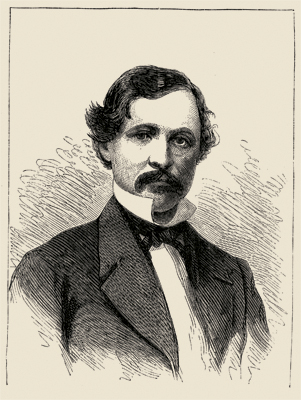

American adventurer and soldier of fortune Frederick Townsend Ward was born in Salem, Mass., on Nov. 29, 1831, but he didn’t remain long in his native state. He went to sea at the age of 15 and by 21 was in Mexico, recruiting men for filibuster William Walker’s ultimately failed attempt to carve out a new republic from that country. Ward later fought as a lieutenant in the French army during the 1853–56 Crimean War and reputedly turned stints as a Texas Ranger and New York shipping clerk before returning to a seafaring life.

On April 20, 1860, Ward arrived in Shanghai aboard a China clipper to establish a trading post for his father’s New York shipping firm. Instead, he soon signed on as executive officer of Confucius, an armed riverboat of Shanghai’s Pirate Suppression Bureau. Formed by local officials, the bureau was funded through a prominent local banker and merchant, Yang Fang, so as to cloak any government association with what Qing rulers publicly decried as Western “foreign devils.” Those same devils commanded and crewed the bureau’s gunboats.

In 1853 the Taiping rebels had captured Nanjing and made it the capital of their Heavenly Kingdom. Their steady gains eroded public faith in the abilities of imperial troops. Thus, when a rebel army advanced on Shanghai in 1860, both local Qing officials and resident foreigners resolved that a force of foreign nationals was needed to protect the city—despite the fact Western governments had officially proclaimed neutrality in the Chinese civil war.

The solution was a force of foreigners with no direct links to any Western government. Ward’s courage and initiative aboard Confucius had impressed prominent people in Shanghai, and that, coupled with Ward’s own vigorous self-promotion, made him an ideal commander of the proposed force. In the spring of 1860 Yang Fang hired Ward to recruit, organize, train and lead the army that was to protect Shanghai against the Taiping rebels. Ward was promised a fortune in excess of $100,000 if by 1862 he had captured Songjiang (Sungkiang), a rebel-occupied town a day’s march from Shanghai. Each of Ward’s soldiers would be paid the equivalent of $50 per month, officers $200 per month, and Ward himself $500 a month, with bonuses for each town recaptured.

Ward scoured the wharves of Shanghai for every Westerner capable of handling a weapon and created the Shanghai Foreign Arms Corps

Ward scoured the wharves of Shanghai for every Westerner capable of handling a weapon and created the Shanghai Foreign Arms Corps. Though he lacked formal military training, Ward was an astute student of warfare and was able to draw on his experiences in Mexico and Crimea. Thinking ahead of his time, he understood frontal assaults against disciplined firing lines were simply a waste of manpower. He instead trained his men in platoon-sized operations that focused on fire and movement and used covering terrain to shelter from enemy fire. Moreover, Ward learned from his mistakes and made adjustments accordingly. High pay, regular food and standard uniforms combined to produce high morale among his troops, whom he referred to as “my people.” Appreciating the critical importance of local popular support, Ward forbade looting, rape and the sacking of cities.

Ward’s initiative to build a Western army to protect Shanghai against the Taiping rebels was not without detractors. Manchu commanders of the imperial army abhorred the idea that an army of Westerners, should it prevail, would expose the relative weakness of their native soldiers. Concurrently, many Western diplomatic officials wanted no foreign involvement in domestic Chinese matters, even by Westerners in Chinese employ. The Western powers were worried the Taiping rebels might blockade lucrative trade down the Yangtze River to Shanghai were Westerners to violate the official neutrality policy. Finally, many of Ward’s recruits were the dregs of society and were often drunk, undisciplined and more than happy to desert.

Despite the many challenges he faced, by June 1860 Ward had a gathered a force of 100 Westerners. He had armed them with the best weapons available and set up a rigorous and comprehensive training regimen. Time was not on his side, however, for when imperial forces moved to attack the Taiping army, Ward’s Shanghai backers forced him to take his Foreign Arms Corps into action alongside the Qing army. The combined forces soon recaptured two towns, but met disaster when they assaulted the fortified and well-defended city of Songjiang without artillery support. The defeated force retreated to Shanghai, but by mid-July Ward had recruited more Westerners—as well as some 80 Filipino “Manilamen”—and obtained several artillery pieces. Ward and his reconstituted force then attacked and took Songjiang, though in the process he lost 62 killed and 100 wounded out of a force of 250. Ward was among those wounded.

On August 2—though only partially recovered from his injuries—Ward led the Foreign Arms Corps against Chingpu (Qingpu), the next town northwest of Songjiang on the approach to Shanghai. Ward was unawaretian the Taiping army holding the city had been reinforced and was prepared to meet the assault. The rebels ambushed the Foreign Arms Corps, which suffered 50 percent casualties within the first 10 minutes. Ward was again wounded, this time by a musket ball to the left jaw, leaving him with a scar and a speech impediment.

Returning to Shanghai for medical treatment, Ward recruited still more replacements and bought additional artillery. He then led his small army back to Chingpu, laying siege to it and extensively bombarding the defenses. Unfortunately for Ward, Loyal King Li Xiucheng, among the most able of the Taiping commanders, had sent 20,000 troops to reinforce Chingpu. Their arrival compelled the Foreign Arms Corps to retreat to Songjiang, its tail tucked between its legs. Li followed. The Taiping commander besieged Shanghai until driven off by French, British and imperial Qing forces.

Ward left Shanghai in late 1860 for further treatment of his severe facial wound, and when he returned in the spring of 1861, he set about rebuilding the Foreign Arms Corps. The high pay he offered attracted many foreigners, including numerous deserters from British warships in port. But the Western governments and wealthy merchants continued to oppose Ward’s activities, to the point of attempting to have him arrested for neutrality violations. The American adventurer outmaneuvered his opponents by renouncing his U.S. citizenship and becoming a Chinese subject. He even married Yang Changmei, a daughter of his patron Yang Fang.

In May 1861 Ward and his Foreign Arms Corps launched a third assault on Chingpu and were again repulsed with heavy casualties. The primary cause of Ward’s defeat was his army’s increasingly poor discipline. The desperate need to replace his earlier losses had required Ward to recruit whatever Westerners he could find in Shanghai and the other port cities, most of whom enlisted only for the money and lacked any real desire to fight. In the wake of this latest failed assault Ward made a momentous decision: The Foreign Arms Corps would no longer be a primarily Western formation—he would begin recruiting Chinese into its ranks.

It was a shrewd move. The predominantly Han people had no love for their Manchu rulers, and many had initially supported the Taiping army out of a desire to oust the hated tyrants. Yet the Taiping kingdom’s supposedly Christian liberators were every bit as brutal to the people they conquered; rampant killing and looting were the norm rather than the exception. Its army also burned and destroyed Buddhist temples, Taoist monasteries and Confucian shrines alike. The people responded to such atrocities by forming militias and waging guerrilla warfare against their “Christian saviors.” When given the opportunity, they joined Ward’s army in droves.

The new Chinese recruits were given European-style uniforms with deep-green Indian sepoy turbans and were drilled in Western weapons, tactics and fighting techniques. Ward taught the men to obey Western bugle calls and other commands and to hold their fire until sure of their targets. The Chinese troops proved both good marksmen and artillerymen, and Ward found them better disciplined than the rebellious Western sailors who had comprised much of the Foreign Arms Corps. He demonstrated his regard for them by providing good wages, clean billets and decent rations. Locals initially derided Ward’s Chinese troops as “imitation foreign devils,” but their mockery turned into respect as the men proved themselves equal to European soldiers in effectiveness.

In January 1862 Taiping’s Loyal King Li Xiucheng set out for Shanghai with an army of 120,000 men. Alerted to Li’s approach, Ward and his army of 1,000 Chinese soldiers marched out to engage the advancing rebels, trudging through snow the 25 miles from Songjiang to Wusong, a dozen miles north of Shanghai. Despite the vastly superior rebel numbers, Ward’s highly mobile force surprised the Taiping troops and drove them from their entrenched positions.

On the return march an emboldened Ward attacked the 20,000-man Taiping garrison at Guangfulin. Though the plucky commander fielded just 500 men and lacked artillery support, his unexpected violent attack drove the town’s defenders from their positions. In February Ward set out with another 500 troops, and in a joint operation with local Qing imperial forces he drove the rebels in turn from Yinchipeng, Chenshan, Tianmashan and other areas around Songjiang. Each time Ward’s army defeated numerically superior enemies; however, he suffered five additional wounds, including the loss of a finger to another musket ball.

A furious Li then sent 20,000 men to attack Songjiang and wipe out the foreign devil threat to the Taiping army. Though fielding only 1,500 men, Ward again displayed superior combined-arms tactical skills. Firing from concealed positions, his artillery decimated the unwary attackers, and his infantry followed up with a lightning counterattack. The Foreign Arms Corps killed more than 2,000 Taiping soldiers, captured another 800 and seized numerous boats bearing rebel supplies and arms.

The victories secured Ward’s reputation among the Chinese, Westerners and the Taiping rebels. That spring the Qing government awarded Ward’s force the title Chang Sheng Jun—Ever Victorious Army. Ward himself was appointed an imperial general of the fourth rank; later, at the recommendation of senior imperial army commander Li Hongzhang, he was promoted to imperial general of the second rank—equivalent to a U.S. lieutenant general and just a step below a full general.

The Ever Victorious Army lived up to its name, time and again defeating numerically superior opponents

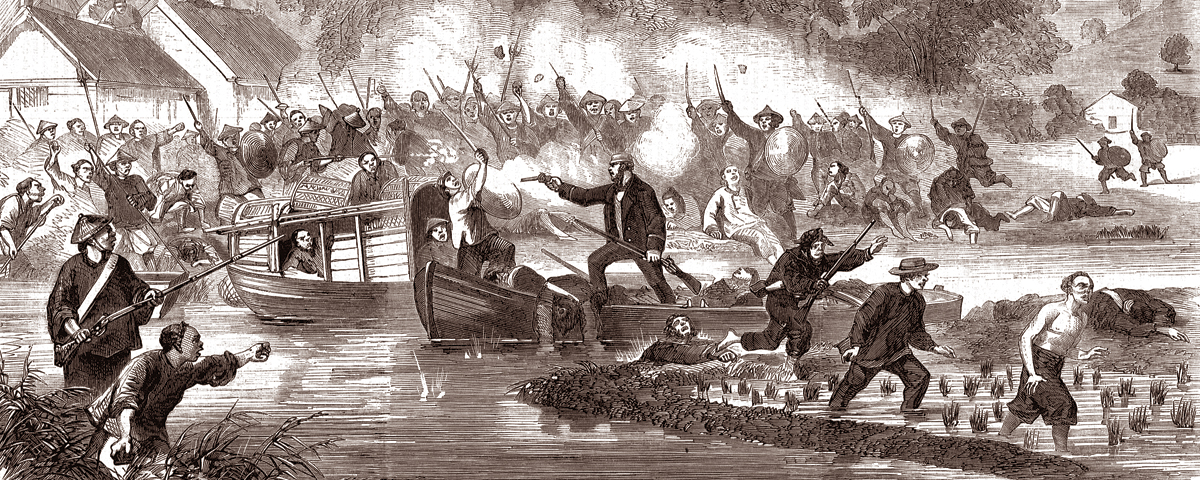

For six months the Ever Victorious Army lived up to its name, time and again defeating numerically superior opponents. In the summer Li Xiucheng led another large Taiping force into the area. To enhance mobility and firepower, Ward effectively employed amphibious tactics, using the rivers and canals crisscrossing the region to transport troops and attack the enemy. He commandeered several river steamers, mounted cannons on them, then used them as troop transports and artillery fire-support bases. His tactics confounded Li, who lamented, “My Taiping army could contend with the foreign devils on land, but [against] his navy I am helpless.”

Ward wanted to march on the Taiping capital at Nanjing, but the Manchu imperial court remained wary of its foreign devil imperial general, even though he was in their employ. For one, he had refused to shave his forehead, wear a pigtail or even appear in his fine Mandarin robes. Then there was the traditional concern about generals who become too popular and powerful. Not unlike Rome, Chinese history was fraught with commanders who had used the army to occupy the dragon throne. Thus the imperial court limited the size of Ward’s unit and restricted his authority to move his army beyond the need to protect Shanghai. During his tenure Ward never fielded more than 5,000 men, and his army never participated in an attack on Nanjing.

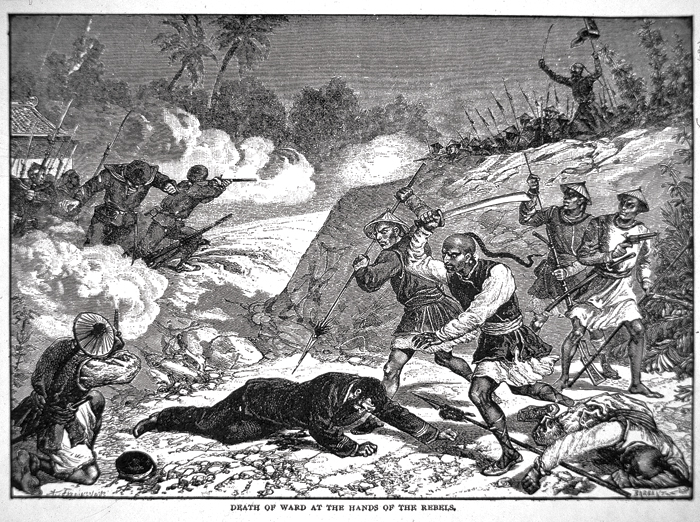

On Sept. 21, 1862, the odds finally caught up with 30-year-old soldier of fortune Frederick Ward, who was mortally wounded by a musket ball to the abdomen while fighting in the coastal town of Cixi, on the south shore of Hangzhou Bay opposite Shanghai. Ironically, he’d been shot by a Western mercenary fighting for the Taiping rebels. It was the 15th and final injury suffered by Ward during his brief military career in China.

On Ward’s death, command of the Ever Victorious Army passed to his second, Edward Forester, then to fellow American adventurer Henry Burgevine, and finally to British officer Charles George Gordon, who as “Chinese Gordon” rode Ward’s creation to fame.

The Qing government bestowed posthumous high honors on their American imperial general. The entire city of Shanghai shut down for a day, and for three months members of the Ever Victorious Army strictly observed a mourning period for their deceased general. The Qing government built a memorial temple and shrine atop Ward’s grave in Songjiang to honor his achievements. Regrettably, both were destroyed in the ensuing years by warfare, and in 1955 communist officials reportedly disinterred and scattered Ward’s bones. However, a cenotaph in his hometown of Salem memorializes Ward, and the imperial general is also remembered at a Nanjing museum and a Roman Catholic church in Songjiang. One unidentified visitor to the church scrawled out an informal eulogy to Ward:

The grave of Ward, a Protestant, revered as a Chinese Confucian hero, with a temple in his honour, now lies under the altar of a Roman Catholic church, whilst the land itself is the property of the local Buddhist monastery in a communist state.…Ward has not been forgotten.

Ward’s accomplishments are documented in the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom Historical Museum in Nanjing (see Hallowed Ground, by Stephen M. Johnson, in the May 2017 issue of Military History). In 1923 American Legion China Post 1 placed a large headstone in Ward’s honor at that site. In fact, that post—formed in 1919 (a year after the Armistice) and chartered by the American Legion the following year—was originally named General Frederick Townsend Ward Post No. 1, China. It is the only post nominally headquartered in a communist country and has been operating in exile since 1948. Today China Post 1 is considered part of the Department of France and is a member of FODPAL (Foreign and Outlying Departments and Posts of the American Legion). It is the post favored by soldiers of fortune, intelligence officers and spooks. The post still has no permanent home, although watering holes around the globe offer space for meetings, which are considered “official” wherever two or more members meet.

Ward’s legacy also endures in popular culture. Author Caleb Carr recounted his life in the 1992 biography The Devil Soldier, and the 2003 epic war film The Last Samurai was based in part on the adventures of Frederick Townsend Ward. MH

Tang Long (aka William Tang) is a consultant on China. He wrote the “Tales of the Dragon” column for WashingtonTimes.com and authored The Book of War, the first chronological account of ancient Chinese military history written in English. For further reading he recommends The Devil Soldier, by Caleb Carr; Ti-ping Tien-Kwoh: The History of the Ti-Ping Revolution, by Augustus F. Lindley; and The Autobiography of the Chung-Wang, by Li Xiucheng.